Xenophobia � Outsider Exclusion Addressing Frail Social Cohesion in South Africa's Diverse Communi�Es

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Road Network Provincial Road Network CLASS, SURFACE P, Concrete L, Blacktop G, Blacktop On-Line Roads !

D 3 0 7 L 0 L 1 6 6 D 6 1 Isifisosethu H 4 Manqondo LP 226 65 2 7 1 2 9 45 9 9 9 6 01 9 1 1 1 6 D P 1 Egweni CP 1 O L 6 7 7 O 4 0 0 L 3 Sizani 0 0 8 Engobhiyeni 0 L 7 L 77 3 1 3 M 4 8 O 9 4 9 O 6 L O 4 1 1 A P/School 1 L 2 9 P 162 0 D 8 8 O L 3 OL01 Engoleleni Cp 1 Hiwemini CP 15 R 1 D 1 0 1 D - 6 63 25 0 N Windy 8 011 O L Kwa- L Gobizembe H OL L0 1 O 11 Hlwemini Cp Zuleka Bhekamafa O Simamane LP 0 64 Windy Hill D 70 497 62 40 D8 0 Mwolokohlo Inglemere O 1 Paruk JS 19 55 87 !. L 0 60 Ekupholeni S Magudwini Js L0 D1 Clinic P3 Mobile Shakas Head Hill CP 0 11 O 513 O Gobizembe H 1 1 OL01159, OL0 1 2 D L Clinic M1 Provincial 7 0 1 Emlandeleni Cp 6 2 L 6 202 O 1 2 Mqedi P 3 4 9 Mob. Base L 1 225 O 5 6 L 01 4 P 1 D 0 Ra Padayachee P 0 4 7 98 0 2 17 Asamukele JP 2 8 9 3 2 1 P 1 1 1 L0 D OL L 2 1 1 Baxoleleni CP 1 O 0 O 2 L 6 11 Mantingwane 0 5 M !. -

City Invests R101m in Housing

21 August - 3 September 2015 Your FREE Newspaper METROezasegagasini www.durban.gov.za NEW FACELIFT WORLD TRADING FOR ISIPINGO CLASS STALLS CENTRE SPORT HUB News: Page 3 News: Page 7 Sports: Page 12 City invests R101m in housing CHARMEL PAYET said. The pilot phase, Phase 1A, HE Executive was at an advanced stage Committee on with 482 top structures on Tuesday, 18 August fully serviced sites. 2015 approved ad- The funding shortfall of ditional funding of R101 million is to ensure TR101 million to ensure the completion of the eight sub- first phase of the Cornubia phases in Phase 1, of which Integrated Human Settle- one, Phase 1B, was already ment Development would at implementation stage. be completed. Additional funds are need- City Manager Sibusiso ed to complete Phase 1B. Sithole said funding had to Currently three contractors be approved to ensure the are engaged with the imple- City was able to meet their mentation of 2 186 sites. housing obligations which Of this 803 sites are ready included the relocation of for top structure construc- several identified transit tion, 741 by another con- camps at the site.“There is tractor will be completed a sense of urgency in this this month while the third matter as we have been contractor will be imple- dealing with it for months. If menting 642 serviced sites. we don’t find a solution we Top structures will be com- will sit with this infrastruc- pleted by April next year. ture which will be wasteful Attempts to find solutions expenditure which we don’t to address the shortfall were want,” he said. -

(Gp) Network List Kwazulu-Natal

WOOLTRU HEALTHCARE FUND GENERAL PRACTITIONER (GP) NETWORK LIST KWAZULU-NATAL PRACTICE AREA PROVIDER NAME TELEPHONE ADDRESS NUMBER ABAQULUSI RURAL 433802 DR KHAYELIHLE NXUMALO 034 9330983 A977 GOBINSIMBI ROAD AMANZIMTOTI 683043 DR ROCHAEL DEBIDEEN 031 9038333 SUITE C5, SEADOONE MALL AMANZIMTOTI 1439502 DADA A T 031 9037170 LAGOON CENTRE, SHOP 7, 361 KINGSWAY ROAD AMANZIMTOTI 1489534 BADUL P D 4 SCHOOL CRESCENT BEREA 473758 TIMOL S 031 2092195 420 RANDLES ROAD BEREA 1495879 RANDEREE S E 031 2072872 249 SPARKS ROAD BEREA 1559753 DR KESHUBANANDA NAIDOO 031 2015281 289 MOORE ROAD BERGVILLE 443883 DR WELCOME VEZI 036 4482929 96 SHARRATT STREET BLUFF 328405 NAIDOO A R 031 4661822 SHOP 14, BLUFF SHOPPING CENTRE, 884 BLUFF ROAD BLUFF 1443747 MAHARAJ A S 031 4611002 217 QUALITY STREET BLUFF 1511548 PILLAY S 031 4685360 NATRAJ CENTRE, SHOP 33, BOMBAY WALK BLUFF 448257 KATHRADA M 031 4671631 658 MARINE DRIVE BROOKDALE 1583344 MAHARAJ N 031 5057436 340 CRESTBROOK DRIVE BULWER 70009 DR SIPHO VISAGIE 039 8320250 SHOP 8, STAVCOM CENTRE CATO RIDGE 1526642 ERASMUS P E & PARTNER 031 7822030 CATO MEDICAL CENTRE, 1 RIDGE ROAD CHATSWORTH 5568 DR ARIVAN MOODLEY 031 4035496 215 CROFTDENE DRIVE CHATSWORTH 517585 DR RYNAL DEVANATHAN 98 LENNY NAIDU DRIVE CHATSWORTH 1423819 SEWPERSAD V 031 4092332 211 HIGH TERRACE, CHATWORTH CHATSWORTH 1427180 SHUNMUGAM S M 031 4049014 110 ARENA PARK DRIVE CHATSWORTH 1461885 BADAT M R S 031 4048498 16 MOORTON DRIVE CHATSWORTH 1473131 PILLAY D 031 4048824 62 ROAD 736 CHATSWORTH 1499564 NUNDLALL H INCORPORATED 031 4041319 33 ROAD -

Ward Councillors Pr Councillors Executive Committee

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE KNOW YOUR CLLR WEZIWE THUSI CLLR SIBONGISENI MKHIZE CLLR NTOKOZO SIBIYA CLLR SIPHO KAUNDA CLLR NOMPUMELELO SITHOLE Speaker, Ex Officio Chief Whip, Ex Officio Chairperson of the Community Chairperson of the Economic Chairperson of the Governance & COUNCILLORS Services Committee Development & Planning Committee Human Resources Committee 2016-2021 MXOLISI KAUNDA BELINDA SCOTT CLLR THANDUXOLO SABELO CLLR THABANI MTHETHWA CLLR YOGISWARIE CLLR NICOLE GRAHAM CLLR MDUDUZI NKOSI Mayor & Chairperson of the Deputy Mayor and Chairperson of the Chairperson of the Human Member of Executive Committee GOVENDER Member of Executive Committee Member of Executive Committee Executive Committee Finance, Security & Emergency Committee Settlements and Infrastructure Member of Executive Committee Committee WARD COUNCILLORS PR COUNCILLORS GUMEDE THEMBELANI RICHMAN MDLALOSE SEBASTIAN MLUNGISI NAIDOO JANE PILLAY KANNAGAMBA RANI MKHIZE BONGUMUSA ANTHONY NALA XOLANI KHUBONI JOSEPH SIMON MBELE ABEGAIL MAKHOSI MJADU MBANGENI BHEKISISA 078 721 6547 079 424 6376 078 154 9193 083 976 3089 078 121 5642 WARD 01 ANC 060 452 5144 WARD 23 DA 084 486 2369 WARD 45 ANC 062 165 9574 WARD 67 ANC 082 868 5871 WARD 89 IFP PR-TA PR-DA PR-IFP PR-DA Areas: Ebhobhonono, Nonoti, Msunduzi, Siweni, Ntukuso, Cato Ridge, Denge, Areas: Reservoir Hills, Palmiet, Westville SP, Areas: Lindelani C, Ezikhalini, Ntuzuma F, Ntuzuma B, Areas: Golokodo SP, Emakhazini, Izwelisha, KwaHlongwa, Emansomini Areas: Umlazi T, Malukazi SP, PR-EFF Uthweba, Ximba ALLY MOHAMMED AHMED GUMEDE ZANDILE RUTH THELMA MFUSI THULILE PATRICIA NAIR MARLAINE PILLAY PATRICK MKHIZE MAXWELL MVIKELWA MNGADI SIFISO BRAVEMAN NCAYIYANA PRUDENCE LINDIWE SNYMAN AUBREY DESMOND BRIJMOHAN SUNIL 083 7860 337 083 689 9394 060 908 7033 072 692 8963 / 083 797 9824 076 143 2814 WARD 02 ANC 073 008 6374 WARD 24 ANC 083 726 5090 WARD 46 ANC 082 7007 081 WARD 68 DA 078 130 5450 WARD 90 ANC PR-AL JAMA-AH 084 685 2762 Areas: Mgezanyoni, Imbozamo, Mgangeni, Mabedlane, St. -

Chapter 9: In-Depth Case Study Analysis

Impact of Township Shopping Centres – July, 2010 CHAPTER NINE: IN-DEPTH CASE STUDY ANALYSIS – UMLAZI MEGA CITY 9.1 INTRODUCTION Umlazi Mega City represents a minor regional centre located in Umlazi, KwaZulu Natal. The purpose of this chapter is multi-fold: Firstly, to provide a profile of the centre under investigation and its location in relation to surrounding supply; Secondly, to provide a socio-economic profile of the primary consumer market of the centre; Thirdly, to provide an overview of past and present consumer market behaviour, overall levels of satisfaction, perceived needs and preferences; Fourthly, to determine the overall impact that the development of the centre had on the local community and economy. 9.2 UMLAZI MEGA CITY PROFILE AND LOCATION WITH REFERENCE TO COMPETITION 9.2.1 UMLAZI MEGA CITY PROFILE Table 9.1 provides a condensed profile of Umlazi Mega City. Overall it is evident that it represents a minor regional centre of 28 000m2 retail GLA, located at 50 Mangosuthu Highway, Umlazi. It was developed in 2006 and consists of a single retail floor with 102 shops and 465 parking bays. It is anchored by Super Spar, Woolworths, Jet and Mr Price. Table 9.1: Umlazi Mega City Profile Centre type Minor regional centre Centre size 28 000m2 retail GLA Location 50 Mangosuthu Highway, Umlazi Date of development 2006 Number of retail floors 1 Number of shops 102 Number of parking bays 465 open Anchor tenants Super Spar Woolworths Jet Mr Price Owner SA Corporate Real Estate Fund Developer Mark II Project Managers Source: Demacon Ex. SACSC, 2010 9.2.2 UMLAZI MEGA CITY LOCATION WITH REFERENCE TO COMPETITION Map 9.1 indicates the location of Umlazi Mega City with reference to existing retail centres within and just beyond a 10km radius. -

R603 (Adams) Settlement Plan & Draft Scheme

R603 (ADAMS) SETTLEMENT PLAN & DRAFT SCHEME CONTRACT NO.: 1N-35140 DEVELOPMENT PLANNING ENVIRONMENT AND MANAGEMENT UNIT STRATEGIC SPATIAL PLANNING BRANCH 166 KE MASINGA ROAD DURBAN 4000 2019 FINAL REPORT R603 (ADAMS) SETTLEMENT PLAN AND DRAFT SCHEME TABLE OF CONTENTS 4.1.3. Age Profile ____________________________________________ 37 4.1.4. Education Level ________________________________________ 37 1. INTRODUCTION _______________________________________________ 7 4.1.5. Number of Households __________________________________ 37 4.1.6. Summary of Issues _____________________________________ 38 1.1. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT ____________________________________ 7 4.2. INSTITUTIONAL AND LAND MANAGEMENT ANALYSIS ___________________ 38 1.2. PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ______________________________________ 7 4.2.1. Historical Background ___________________________________ 38 1.3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ________________________________________ 7 4.2.2. Land Ownership _______________________________________ 39 1.4. MILESTONES/DELIVERABLES ____________________________________ 8 4.2.3. Institutional Arrangement _______________________________ 40 1.5. PROFESSIONAL TEAM _________________________________________ 8 4.2.4. Traditional systems/practices _____________________________ 41 1.6. STUDY AREA _______________________________________________ 9 4.2.5. Summary of issues _____________________________________ 42 1.7. OUTLINE OF THE REPORT ______________________________________ 10 4.3. SPATIAL TRENDS ____________________________________________ 42 2. LEGISLATIVE -

DURBAN NORTH 957 Hillcrest Kwadabeka Earlsfield Kenville ^ 921 Everton S!Cteelcastle !C PINETOWN Kwadabeka S Kwadabeka B Riverhorse a !

!C !C^ !.ñ!C !C $ ^!C ^ ^ !C !C !C!C !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C $ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ ñ!C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^ !C ^ !C ñ!C !C ^ ^ !C !C $ ^!C $ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C ñ!.^ $ !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C $ !C !C ñ $ !. !C !C !C !C !C !C !. ^ ñ!C ^ ^ !C $!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !. !C !C ñ!C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ ^ $ ^ !C ñ !C !C !. ñ ^ !C !. !C !C ^ ñ !. ^ ñ!C !C $^ ^ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !C !. ñ !C !C ^ !C ñ!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C !. !C ^ !. !. !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ñ !C !. -

Province Physical Suburb Physical Town Physical

PROVINCE PHYSICAL SUBURB PHYSICAL TOWN PHYSICAL ADDRESS1 PRACTICE NAME CONTACT NUMBER PRACTICE NUMBER Kwa Zulu Natal Berea Berea Life Entabeni Hospital,148 Mazisi Kunene (South Ridge Road), Patel R & and Partners t/a East Rand Dialysis Inc. 0114210286 9902767 Berea, Durban Kwa Zulu Natal Glenwood Berea 260-262 Clark Road -Glenwood, Durban, Kwa Zulu Natal Fresenius Medical Care South Africa (Pty) Ltd 0312611211 9903267 Kwa Zulu Natal Woodhurst Chatsworth 65 Gemini Crescent . Woodhurst, Durban Fresenius Medical Care South Africa (Pty) Ltd 031 -4020264 9903259 Kwa Zulu Natal Woodhurst Chatsworth Life Chatsmed Hospital, C/O Biyela Street & Ukula Street, Patel R & and Partners t/a East Rand Dialysis Inc. 0114210286 9902775 Woodhurst, Chatsworth Kwa Zulu Natal Durban Durban 86 Charlotte Maxeke Street, Durban Central D Mahabeer t/a Ultra Kidney Care 0313959600 9901191 Kwa Zulu Natal Durban Durban Shifa Hospital, 482 Randles Rd Durban Renal Care Team Inc. 084 7582090 9904468 Kwa Zulu Natal Durban Durban City Hospital 83 Ismail C Meer Str, Durban Renal Care Team Inc. 0313143000 9904425 Kwa Zulu Natal Durban Durban 460 Anton Lembede Street, Durdoc Medical Centre, Durban, Kzn Renal Care Team Inc. 0313012532 9902988 Kwa Zulu Natal Greyville Durban Ascort Hospital, 3 Ascot St Greyville, Durban Renal Care Team Inc. 084 7582090 9904433 Kwa Zulu Natal Kwamashu Durban Medicare Medical Center, 175 Nyala Rd, L Section, Kwamashu, Renal Care Team Inc. 0315011006 9903003 Durban Kwa Zulu Natal Newlands East Durban Ethekweni Hospital, 11 Riverhorse Rd Newlands -

South African Crime Quarterly 57

The killing fields of KZN Local government elections, violence and democracy in 2016 Mary de Haas* [email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2016/v0n57a456 This article explores the intersections between party interests, democratic accountability and violence in KwaZulu-Natal. It begins with an overview of the legacy of violence in the province before detailing how changes in the African National Congress (ANC) since the 2007 Polokwane conference are inextricably linked to internecine violence and protest action. It focuses on the powerful eThekwini Metro region, including intra-party violence in the Glebelands hostel ward. These events provide a crucial context to the violence preceding the August 2016 local government elections. The article calls for renewed debate about how to counter the failure of local government. In KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), the province dubbed the Glebelands hostel ward. Crucially, it also the ‘killing fields’ in the early 1990s, all post- contextualises the violence that preceded the 1994 elections have been marked by intimidation August 2016 local government elections. and violence. In the past decade intra-party Political violence 1994–2015 conflict, especially over the nomination of local government ward candidates, has increased. The violence that engulfed KZN in the 1980s In 2011 the conflict within the African National and early 1990s continued for several years Congress (ANC) went beyond individual after the 1994 elections, with an estimated competition and was symptomatic of increasing -

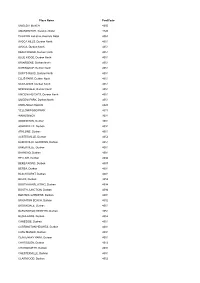

Place Name Postcode UMDLOTI BEACH 4350 AMANZIMTOTI

Place Name PostCode UMDLOTI BEACH 4350 AMANZIMTOTI, Kwazulu Natal 4126 PHOENIX Industria, Kwazulu Natal 4068 AVOCA HILLS, Durban North 4051 AVOCA, Durban North 4051 BEACHWOOD, Durban North 4051 BLUE RIDGE, Durban North 4051 BRIARDENE, Durban North 4051 DORINGKOP, Durban North 4051 DUFF'S ROAD, Durban North 4051 ELLIS PARK, Durban North 4051 NEWLANDS, Durban North 4051 SPRINGVALE, Durban North 4051 UMGENI HEIGHTS, Durban North 4051 UMGENI PARK, Durban North 4051 UMHLANGA ROCKS 4320 YELLOWWOOD PARK 4011 WANDSBECK 3631 ADDINGTON, Durban 4001 ASHERVILLE, Durban 4091 ATHLONE, Durban 4051 AUSTERVILLE, Durban 4052 BAKERVILLE GARDENS, Durban 4051 BAKERVILLE, Durban 4051 BAYHEAD, Durban 4001 BELLAIR, Durban 4094 BEREA ROAD, Durban 4007 BEREA, Durban 4001 BLACKHURST, Durban 4001 BLUFF, Durban 4052 BOOTH AANSLUITING, Durban 4094 BOOTH JUNCTION, Durban 4094 BOTANIC GARDENS, Durban 4001 BRIGHTON BEACH, Durban 4052 BROOKDALE, Durban 4051 BURLINGTON HEIGHTS, Durban 4051 BUSHLANDS, Durban 4052 CANESIDE, Durban 4051 CARRINGTON HEIGHTS, Durban 4001 CATO MANOR, Durban 4091 CENTENARY PARK, Durban 4051 CHATSGLEN, Durban 4012 CHATSWORTH, Durban 4092 CHESTERVILLE, Durban 4001 CLAIRWOOD, Durban 4052 CLARE Est/Lgd, Durban 4091 CLAYFIELD, Durban 4051 CONGELLA, Durban 4001 DALBRIDGE, Durban 4001 DORMERTON, Durban 4091 DURBAN NORTH, Durban 4051 DURBAN-NOORD, Durban 4051 Durban International Airport, Durban 4029 EARLSFIELD, Durban 4051 EAST END, Durban 4018 EASTBURY, Durban 4051 EFFINGHAM HEIGHTS, Durban 4051 FALLODEN PARK, Durban 4094 FLORIDA ROAD, Durban 4019 FOREST -

Kwazulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal Municipality Ward Voting District Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830014 INDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.99047 29.45013 NEXT NDAWANA SENIOR SECONDARY ELUSUTHU VILLAGE, NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830025 MANGENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.06311 29.53322 MANGENI VILLAGE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830081 DELAMZI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09754 29.58091 DELAMUZI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830799 LUKHASINI PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.07072 29.60652 ELUKHASINI LUKHASINI A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830878 TSAWULE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.05437 29.47796 TSAWULE TSAWULE UMZIMKHULU RURAL KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830889 ST PATRIC JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.07164 29.56811 KHAYEKA KHAYEKA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830890 MGANU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -29.98561 29.47094 NGWAGWANE VILLAGE NGWAGWANE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11831497 NDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.98091 29.435 NEXT TO WESSEL CHURCH MPOPHOMENI LOCATION ,NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKHULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830058 CORINTH JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09861 29.72274 CORINTH LOC UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830069 ENGWAQA JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.13608 29.65713 ENGWAQA LOC ENGWAQA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830867 NYANISWENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.11541 29.67829 ENYANISWENI VILLAGE NYANISWENI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830913 EDGERTON PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.10827 29.6547 EDGERTON EDGETON UMZIMKHULU -

2017-Research-Day-Proceedings.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF ™ ••...{.,, KWAZULU-NATAL COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE, '{' INYUVESI � YAKWAZULU-NATALI ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE The College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science would like to express its grateful thanks to the following external partners of the 2017 College Postgraduate Research and Innovation Day: agriculture National & rural development Depettmenl: Research Agrb.,ltureendRLOIDeveloprnent RF Foundation �IIIP!> PROVINCE OF KWAZULU-NATAL • B·;,ft1J�-SCH WiRSHIII �- Anton Paar ULWAZI SCIENTIFIC � f> PerkinElmer f\ �Accreditationu�tn !1� System1 citrus� ARC•LNR�� h:chnoloq4 innovation acacJemy A G E N C Y inqaba biotec - Africa's Genomlcs Company EC SA ELSEVIER enterprisingIT and beuand NATIONALASTROPHYSICS AND SPACE SCIENCE PROGRAMME NASS..,,.� UNITED80 SCIENTIFIC"'..., Lasec �c.,'?!=��pplJ.s cc ®Eskom SHALOM � LABORATORY • WhiteSci " ,, ,, ' I SUPPLIES CC -•'' CELTIC�� ll.Metrohm MOLECULAR DIAGNOSTICS UMGENI Industrial Analytical ••••LWW (Pty) Ltd WATER ·AMANZI • ,so ,001:2000 Part of LGC Standards College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science Postgraduate Research and Innovation Day 2017 Westville Campus The College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science would like to express its grateful thanks to the following internal partners of the 2017 College Postgraduate Research and Innovation Day: UKZN School of Agricultural, Earth and Environmental Sciences UKZN School of Chemistry and Physics UKZN School of Engineering UKZN School of Life Sciences UKZN School of Mathematics, Statistics and Computer Science UKZN Information