Running Head: EVALUATING the REDISCOVERY PROCESS 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inquiry Into NHS Service Provision for ME/CFS

All-Party Parliamentary Group on ME Inquiry into NHS Service Provision for ME/CFS March 2010 All-Party Parliamentary Group on ME Inquiry into NHS Service Provision for ME/CFS Contents Foreword 3 Introduction 4 Limitations of the Inquiry 4 Review of Current Treatments 4 Review of Adult Services 9 Review of Children’s Services 12 Training 14 Research 16 Disability and Benefits 16 Conclusion 17 Recommendations 18 Appendix 1: APPG Inquiry on NHS service provision for people with ME: Terms of reference 21 References 24 2 All-Party Parliamentary Group on ME Inquiry into NHS Service Provision for ME/CFS Foreword The All Party Parliamentary Group on M.E. (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis) strives to support the improvement of health and social care of all people with M.E. in the UK. The APPG accepts the WHO Classification of M.E. (ICD G93.3) as a neurological condition and welcomed the recognition by the Department of Health that M.E. is a long term neurological condition. Department of Health funding in 2004/05 and 2005/06 resulted in the establishment of 13 Clinical Network Coordinating Centres and some 50 Local Multidisciplinary Teams. However subsequent changes in NHS organisation and budget setting arrangements have since made it far more difficult to establish the level of investment into the care of these patients. It has also become apparent that some of these newly established secondary services are having to cope with significant reductions in funding. As a result, some have either closed or are under threat of closure. Patient group surveys and letters to MPs and members of the House of Lords continue to identify high levels of patient concern about the services which are being provided and further concerns about the way in which the recommendations contained in the 2007 guideline on ME/CFS from NICE could result in an inflexible approach to management. -

The Rise and Fall of the Wessely School

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE WESSELY SCHOOL David F Marks* Independent Researcher Arles, Bouches-du-Rhône, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, 13200, France *Address for correspondence: [email protected] Rise and Fall of the Wessely School THE RISE AND FALL OF THE WESSELY SCHOOL 2 Rise and Fall of the Wessely School ABSTRACT The Wessely School’s (WS) approach to medically unexplained symptoms, myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome (MUS/MECFS) is critically reviewed using scientific criteria. Based on the ‘Biopsychosocial Model’, the WS proposes that patients’ dysfunctional beliefs, deconditioning and attentional biases cause illness, disrupt therapies, and lead to preventable deaths. The evidence reviewed here suggests that none of the WS hypotheses is empirically supported. The lack of robust supportive evidence, fallacious causal assumptions, inappropriate and harmful therapies, broken scientific principles, repeated methodological flaws and unwillingness to share data all give the appearance of cargo cult science. The WS approach needs to be replaced by an evidence-based, biologically-grounded, scientific approach to MUS/MECFS. 3 Rise and Fall of the Wessely School Sickness doesn’t terrify me and death doesn’t terrify me. What terrifies me is that you can disappear because someone is telling the wrong story about you. I feel like that’s what happened to all of us who are living this. And I remember thinking that nobody’s coming to look for me because no one even knows that I went missing. Jennifer Brea, Unrest, 20171. 1. INTRODUCTION This review concerns a story filled with drama, pathos and tragedy. It is relevant to millions of seriously ill people with conditions that have no known cause or cure. -

ME Is Not a Functional Disorder

ME Association Recipient: Sir Andrew Dillon Letter: Greetings, M.E. is not a functional disorder Comments Name Location Date Comment Carol Bryant Mottram, 2017-09-27 My daughter has ME and clearly this illness is NOT in her England, UK mind it is a physical illness Clare Crofts Rochdale, 2017-09-27 My daughter had Very Severe ME for the last 6years, was England, UK diagnosed as terminal 18 months ago and died in May this year. This disease is horrendous and needs the medical community to take it seriously Sheena young Prestatyn, 2017-09-27 M.E is not a functional disorder and should not be treated as Wales, UK such. Julie Holliday Shrewsbury, 2017-09-27 I have ME and have been treated appallingly by the NHS. England, UK Paul Winter Hailsham, 2017-09-27 I have ME. Some hospitals, such as the National England, UK Neurological Hospital in Queen Square, London, are already routinely ignoring the NICE guidelines and diagnosing people with ME as having FND. This is unacceptable given the mounting evidence that ME is a neuro-imune disease. Jane Iles Cheddar, 2017-09-27 This is too important. NICE need to look at the facts and England, UK listen to ME specialists and more importantly, the sufferers Kathie Cortese UK 2017-09-27 I have got M.E and I know it's not a " functional disorder" NICE need to use more recent up-to-date world studies, and consult with ME patients, and experts on ME Jayne Glover Warminster, 2017-09-27 I don't want other people to suffer the indignity and England, UK humiliation that I have endured for the last 15 years. -

Growing Evidence of an Emerging Tick-Borne Disease That Causes A

For Lyme Disease Awareness and Action Senate Inquiry Submission My Story • Name: Sara Franzoni • Age: 31 • • • • I want my story to be public About my journey • I acquired Lyme-like illness at: Allansford VIC 3277 • I have left Australia. • Type of Bite: no memory of the bite • I was sick for 17 years before I was diagnosed • I have a positive blood test from Igenix laboratory and a negative blood test from Melbourne Pathology • I tested positive for Borrelia Burgdorferi, Pyrrole Disorder, Glandular Fever. • I have seen approximately 50 doctors and medical practitioners in my journey. • I have been admitted to hospital twice for my illness. • I have also been diagnosed with CFS, Glandular Fever, IBS, Adrenal Fatigue, Bilateral Carpal Tunnel, Leaky Gut, Pyrrole Disorder, Depression, Anxiety, Q Fever, Rickettsia. My life • Prior to my illness, my life was unburdened, free and energetic. I was diagnosed at 14, so I was just a kid – but I still remember feeling different in my body prior to experiencing the illness. I would wake every morning excited and with so much energy for the day. I felt light, and I ‘buzzed’. I was naturally athletic and played a lot of sports. I grew up in the country in a dairy farming area. When I first started showing symptoms at age 14 (1998) most doctors in the area simply did not know how to treat me. I had blood tests (particularly for glandular fever) that showed nothing. At first I was told it was post- viral fatigue syndrome. Then when the symptoms continued for 6 months we finally saw another doctor in Warrnambool who diagnosed me with CFS. -

Hay Fever and Allergies, a Homeopathic

Harmony Centre News The perfect setting for healing, learning and development Spring 2008 No. 6 ith the New Year come some positive changes at the Harmony Centre. One most welcome development is that we now have receptionist cover full time at the centre, from Monday to Friday. Generally, our reception Wwill be manned from 9am to 1pm and 2pm to 6pm, five full days a week. If you call, someone will be there to help with your query. Also, if you would like to drop into the centre, it is open to welcome visitors. Our receptionists Lucietta, Tricia, Val and Janet are there to help with your queries. The centre has had a couple of additions to practitioners, see below for what sounds like some exciting new work on offer. The Harmony Room continues to host classes, meetings, workshops and courses. It is a spacious and inspiring room, so why not consider it for your next function. Finally, Thursday evening events are back! See the pull-out sheet inside for details of events up to Easter. Wishing you health and happiness in 2008. New light for ME and chronic fatigue ate Simpson and Steve Kate had ME for nearly five years and used the Lightning Fawdry have recently joined Process to get well. She also used it to recover from depres- Kthe Harmony Centre. They sion and anxiety caused by childhood traumas. Steve used the specialise in teaching the Lightning Process to clear the fatigue he had since having glandular fever Process which enables sufferers of as a teenager, and then went on to use it to recover from hay ME and other chronic conditions to fever and asthma too. -

A Systematic Review of the Evidence Base for the Lightning Process

A systematic review of the evidence base for the Lightning Process P Parker (a)*, J Aston (b), L de Rijk (b) a School of Psychology, London Metropolitan University, 166-220 Holloway Rd, N7 8DB b Kings College London Abstract Background The Lightning Process (LP), a mind-body training programme, has been applied to a range of health problems and disorders. Studies and surveys report a range of outcomes creating a lack of clarity about the efficacy of the intervention. Objective This systematic review evaluates the methodological quality of existing studies on the LP and collates and reviews its reported efficacy. Data sources Five databases, PsycINFO, PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, ERIC (to September 2018), and Google and Google Scholar were searched for relevant studies. Study Selection Studies of the LP in clinical populations published in peer-reviewed journals or in grey literature were selected. Reviews, editorial articles and studies/surveys with un-reported methodology were excluded. Data extraction Searches returned 568 records, 21 were retrieved in full text of which 14 fulfilled the inclusion criteria (ten quantitative studies/surveys and four qualitative studies). Data synthesis and Conclusions The review identified variance in the quality of studies across time; earlier studies demonstrated a lack of control groups, a lack of clarity of aspects of the methodology and potential sampling bias. Although it found a variance in reported patient outcomes, the review also identified an emerging body of evidence supporting the efficacy of the LP for many participants with fatigue, physical function, pain, anxiety and depression. It concludes that there is a need for more randomised controlled trials to evaluate if these positive outcomes can be replicated and generalised to larger populations. -

CONTENTS Chairs Report April 2009 – April 2010 Chairman Report Page 1 Review of the Year & 2 It Has Been a Busy and Eventful Year

Serving ME/CFS patients, carers and interested parties in Glamorgan May/June 2010 Issue 16 CONTENTS Chairs Report April 2009 – April 2010 Chairman Report Page 1 Review of the year & 2 It has been a busy and eventful year. The first event took place at the Thornhill centre on 6th April. We invited Kay Jen- AGM and Thera- Page 3 pies Day kins, from the Cardiff and Vale Coalition for Disabled People to give a talk on Direct Payments, how to get them and who is Membership Page 4 entitled etc. Money Due. Tea In The Park. 11th May; an event was held in conjunction with ME Aware- Xmas 09 Report ness week. The event entailed an excellent and informative Helping Hands. Page 5 talk by a GP on food allergy and intolerance, followed by a Book List. recorded interview between M.E sufferer Andreas Constanti- £164,000 For Re- Page 6 search Into Light- nou and Able Radio, the new internet radio station for people ning Process & with illness or disability. Dr Esther Crawley, who is a chil- Children With ME. dren‘s M.E specialist, was also interviewed about the condi- Recovery Story Page 7 tion. Recipe Page 8 Poem Page 9 1st June; Louise Tindal, a former M.E sufferer and member Severe ME info Page 10 Pack. attended a support group meeting and offered free taster ses- Private Dr Is Page 11 sions in holistic therapies. Lots of people had an Indian Head Given Drugs Ban massage. It was lovely to see people floating out afterwards, Benefit s & Work Page 12 stress free. -

2017 Authors Author Address Title Publication

2017 Authors Author Title Publication Abstract address [No authors listed] RE: "MULTI-SITE CLINICAL Am J Epidemiol. 2017 ASSESSMENT OF MYALGIC Jul 1;186(1) :129. ENCEPHALOMYELITIS/CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME (MCAM) : DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION OF A PROSPECTIVE/RETROSPECTIVE ROLLING COHORT STUDY". [No authors listed] Correction for Naviaux et al., Proc Natl Acad Sci U Erratum for Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Sep 13;113(37) :E5472- Metabolic features of chronic S A. 2017 May 80. fatigue syndrome. 2;114(18) :E3749. ABDULLA J(15) , Torpy Research Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. In: De Groot LJ(1) , et Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a common, enigmatic medical BDJ(16) . Professor, Cell al. editors. Endotext condition comprising mental and physical fatigue, diagnosed after and Molecular [Internet]. South exclusion of possible medical causes. The prominence of post- Biology, Dartmouth (MA) : exertional exacerbation of fatigue is highlighted by the recently College of the MDText.com, Inc.; suggested re-naming as Syndrome of Exertional Intolerance Disease Environment 2000-. 2017 Apr 20. (SEID) . Diagnosis is syndromic. No clinical test can confirm the and Life presence of CFS. Treatment is supportive with no specific therapy Sciences, shown to be reproducibly effective. There are several categories of University of hypotheses regarding CFS aetiology including infections, immune, Rhode Island, mitochondrial, neurobehavioural or stress system (HPA axis and Kingston, RI sympathetic nervous system) disorders. Recently, fatigue disorders have been popularly referred to as “adrenal fatigue.― Although CFS and the syndromically related fibromyalgia have been shown to have lower HPA axis function especially reduced cortisol, when analysed compared to controls in aggregate, and in some cases excessive sympathetic nervous system usually sympathoneural system responses, these findings overlap with controls and such testing is not diagnostic. -

FREE||| an Introduction to the Lightning Process: The

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LIGHTNING PROCESS: THE FIRST STEPS TO GETTING WELL FREE DOWNLOAD Phil Parker | 280 pages | 24 Sep 2012 | Hay House UK Ltd | 9781781800577 | English | London, United Kingdom Getting Started with Salesforce: 3 Simple Steps for Beginners Alternative medicine Alternative veterinary medicine Quackery Health fraud History of alternative medicine An Introduction to the Lightning Process: The First Steps to Getting Well of modern medicine Pseudoscience Antiscience Skepticism Skeptical movement National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Terminology of alternative medicine. Vasant Lad. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Traditional medicine. October Following the initial email, you will be contacted by the shop to confirm that your item is available for collection. About the Author: Brad Smith. Retrieved 4 October Stock photo. Retrieved 12 February Please try again or alternatively you can contact your chosen shop on or send us an email at. Louise Hay. Your review has been submitted successfully. Manage In Explorer. The Lightning Process comprises three group sessions conducted on three consecutive days, lasting about 12 hours altogether, conducted by trained practitioners. Buy It Now. Your settings are good to go. Diagnoses Adrenal fatigue Aerotoxic syndrome Candida hypersensitivity Chronic Lyme disease Electromagnetic hypersensitivity Heavy legs Leaky gut syndrome Multiple chemical sensitivity Wilson's temperature syndrome. You will need to include the name of the opportunity, the account name, who on your team owns that opportunity, and the close date of the deal. Check it off. Namespaces Article Talk. And keep an eye on your analytics! Now, your opportunities will be organized by their current journey stage. -

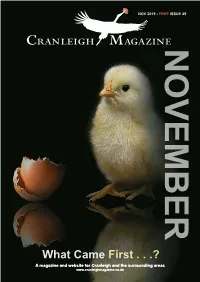

What Came First . . .? a Magazine and Website for Cranleigh and the Surrounding Areas CRANLEIGH MAGAZINE

CRANLEIGH MAGAZINE NOV 2019 - FREE ISSUE 49 NOVEMBER What Came First . .? A magazine and website for Cranleigh and the surrounding areas www.cranleighmagazine.co.uk CRANLEIGH MAGAZINE CELEBRATING 25 YEARS WITH THE LAUNCH OF OUR NEW SHALFORD SHOWROOM IN GUILDFORD SHALFORD SHOWROOM RICHMOND SHOWROOM 7 KINGS ROAD 1-3 POPLAR COURT PARADE SHALFORD RICHMOND ROAD GUILDFORD GU4 8JU TW1 2DT TEL • 01483 277166 TEL • 01483 277166 [email protected] www.aspectkitchens.com Tel: 01403 751 873 Email: [email protected] Tel: 01403 751 873 Email: [email protected] 2 courses2 courses – £–2 £52.955.95 | 33 courses courses – £ 30– .95£30 .95 Tel: 01403 751 873 Email: [email protected] Blue Cheese, Celery & Pear Soup With No7 Blue Monday by Alex James, served with a fresh Jengers Mead Bakery Harvester slice Blue Cheese, Celery & Pear Soup With No7 Blue Monday by AlexHomemade James, served Chicken with Liver a& fresh Cognac Jengers Pate Mead Bakery Harvester slice served with sweet and sour onions & crostinis drizzled with homemade pesto Homemade Chicken Liver & Cognac Pate served with sweet and sourHome onions Cured & crostinisTrout Gravalax drizzled with homemade pesto local Chalk Stream Trout cured with Silent Pool Gin served with horseradish cream & crostinis Christmas Pudding served the way youWild like Mushrooms Homeit let that Cured be in with a Light Troutbrandy Cream Gravalaxsauce & orChive homemade sauce vanilla custard local Chalk Streamon a Jengers Trout Mead cured Harvester with Silent slice topped Pool withGin -

Working with the Science Media Centre

With thanks to our sponsors Contents Editor’s foreword Geoff Watts, science writer and broadcaster The following organisations have contributed to the costs of the Science Media Centre’s 10th anniversary: aybe I’m entirely the wrong person to have publication of their own research through to distant BIVDA, BP plc, British Pharmacological Society, EUK Consulting, GlaxoSmithKline, Imperial College London, Editor’s foreword 1 collated these reflections on the Science Media events of which they have the specialised knowledge or Maudsley Charity, MSD, National Grid, Society for Applied Microbiology, Society for General Microbiology, MCentre (SMC). A decade ago, when I first heard understanding required to offer authoritative comment. Springer Science+Business Media, Wellcome Trust Chief Executive’s introduction 2 of the proposal to set up another body to help science Many of the issues tackled by the SMC are important not journalists do their job properly (which was how I then only for the science involved, but because that science Climate of crisis 4 perceived it), I really couldn’t see the point. Didn’t we all has an impact on society. This is clearly so of the topics GM on trial 6 have our own contact lists? Hadn’t every university and chosen for this booklet. every research institute got a press office eager to alert GM on trial again 8 us to their latest findings? Didn’t science and medical As many of the authors of the following accounts are journalists already get enough press information from keen to emphasise, even those among them who were Media meltdown 10 enough organisations without another body clamouring initially apprehensive about meeting the media have found the experience unthreatening and even enjoyable. -

New Solutions for Health and Wellbeing

Do you feel stuck? New Solutions for Health and Wellbeing Phil Parker Lightning Process Alan Priestley - Practitioner "The results are extraordinary - seeing is believing." Mary King, Olympic Horsewoman Welcome! I’ve written this information pack to guide you through the important journey back to health and wellbeing with the Lightning Process (LP). I hope it will answer the main questions that I’ve found most people have at this point. If you need any extra information, or want to chat anything through with us, please do get in contact with Alan Priestley ,your local practitioner, or our head office team. I wish you great success in your journey and look forward to hearing all about it! Best wishes Phil Parker "I am convinced it is the most powerful way to make rapid and lasting changes in any area of your life." Austin Healey, England Rugby International Page 2 Phil Parker Phil Parker designed the LP over 15 years ago; today he works at his London clinic with a team of experienced practitioners. Phil is an internationally renowned lecturer, therapist and innovator in the field of personal development. He has an international reputation as one of the foremost Hypnotherapists, Executive Coaches, Master Trainers of NLP, and Osteopaths, having worked in these fields since the 1980s. He is the Director of the Phil Parker Training Institute where he designs programmes, researches and trains postgraduate students in the LP, Clinical Hypnotherapy, NLP and Life Coaching. Phil has written and designed books and audio programmes giving a unique perspective which provides new solutions to meet the challenges and opportunities of life in the 21st century.