Everyday Life After Downshifting: Consumption, Thrift and Inequality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sexual Politics of Meat by Carol J. Adams

THE SEXUAL POLITICS OF MEAT A FEMINISTVEGETARIAN CRITICAL THEORY Praise for The Sexual Politics of Meat and Carol J. Adams “A clearheaded scholar joins the ideas of two movements—vegetari- anism and feminism—and turns them into a single coherent and moral theory. Her argument is rational and persuasive. New ground—whole acres of it—is broken by Adams.” —Colman McCarthy, Washington Post Book World “Th e Sexual Politics of Meat examines the historical, gender, race, and class implications of meat culture, and makes the links between the prac tice of butchering/eating animals and the maintenance of male domi nance. Read this powerful new book and you may well become a vegetarian.” —Ms. “Adams’s work will almost surely become a ‘bible’ for feminist and pro gressive animal rights activists. Depiction of animal exploita- tion as one manifestation of a brutal patriarchal culture has been explored in two [of her] books, Th e Sexual Politics of Meat and Neither Man nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals. Adams argues that factory farming is part of a whole culture of oppression and insti- tutionalized violence. Th e treatment of animals as objects is parallel to and associated with patriarchal society’s objectifi cation of women, blacks, and other minorities in order to routinely exploit them. Adams excels in constructing unexpected juxtapositions by using the language of one kind of relationship to illuminate another. Employing poetic rather than rhetorical techniques, Adams makes powerful connec- tions that encourage readers to draw their own conclusions.” —Choice “A dynamic contribution toward creating a feminist/animal rights theory.” —Animals’ Agenda “A cohesive, passionate case linking meat-eating to the oppression of animals and women . -

Opportunities of Frugality in the Post-Corona Era

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Herstatt, Cornelius; Tiwari, Rajnish Working Paper Opportunities of frugality in the post-Corona era Working Paper, No. 110 Provided in Cooperation with: Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH), Institute for Technology and Innovation Management Suggested Citation: Herstatt, Cornelius; Tiwari, Rajnish (2020) : Opportunities of frugality in the post-Corona era, Working Paper, No. 110, Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH), Institute for Technology and Innovation Management (TIM), Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/220088 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

Ethical Consumption As a Reflection of Self-Identity

Ethical consumption as a reflection of self-identity Hanna Rahikainen Department of Marketing Hanken School of Economics Helsinki 2015 HANKEN SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS Department of Marketing Type of work: Master’s Thesis Author: Hanna Rahikainen Date: 31.7.2015 Title of thesis: Ethical consumption as a reflection of self-identity Abstract: In recent years, people’s increasing awareness of ethical consumption has become increasingly important for the business environment. Although previous research has shown that consumers are influenced by their ethical concerns, ethical consumption from a consumer perspective lacks understanding. As self-identity is an important concept in explaining how consumers relate to different consumption objects, relating it to ethical consumption is a valuable addition to the existing body of research. As the phenomenon of ethical consumption has been widely studied, but the literature is fragmented covering a wide range of topics such as sustainability and environmental concerns, the theoretical framework of the paper portrays the multifaceted and complex nature of the concepts of ethical consumption and self-identity and the complexities existing in the relationship of consumption and self-identity in general. The present study took a qualitative approach to find out how consumers define what ethical consumption is to them in their own consumption and how self-identity was related to ethical consumption. The informants consisted of eight females between the ages of 25 – 29 living in the capital area of Finland. The results of the study showed an even greater complexity connecting to ethical consumption when researched from a consumer perspective, but indicated clearly the presence of a plurality of identities connected to ethical consumption, portraying it as one of the behavioural modes selected or rejected by an active self. -

Institutional Entrepreneurship and Permaculture: a Practice Theory Perspective

Institutional entrepreneurship and permaculture: a practice theory perspective Article (Accepted Version) Genus, Audley, Iskandarova, Marfuga and Brown, Chris Warburton (2021) Institutional entrepreneurship and permaculture: a practice theory perspective. Business Strategy and the Environment. pp. 1-14. ISSN 0964-4733 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/95322/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Institutional -

Oythe of Cheap

LIVING FULLY • Spirit the Mariellen Ward oydiscovers that living of simply doesn’t just make good financial cheap sense. It’s a joyous way to be. Illustration: Kagan McLeod My friend Shelly Rowen and I were stretched out on the grass on our blue yoga mats. The summer sun was beating down on the unadorned and unshaded backyard of my rented flat. We were talking about the economy and our shrinking incomes when she said, “I’m using up all of my old lipsticks, the ones that are just nubs. And I’m using up all of my bottles of hand cream and moisturizer too, before I buy more.” “I’m watching for specials at the grocery store,” I said. “And I choose local items, such as apples, rather than fancy imported items, such as Japanese pears.” And then I noticed something: Shelly was smiling. And so was I. This was the moment when I was surprised to discover that I was actually enjoying frugality. I didn’t feel down about it, and neither did Shelly. In fact, we both felt good about our fiscally and environmentally responsible ways. I realized that we had both embraced the idea that living simply can be deeply satisfying. You can be frugal and joyful. And that’s what’s different about the new frugality. In the past, thrift always felt thin-lipped and dour to me. My parents lived through the Great Depression, which, at least in books and movies about those days, seems like it was hard and grim. But a paradigm shift is underway that includes a new awareness of the impact human behaviour is having on the environment and a growing realization that all of the stuff we surround ourselves with does not make us any happier. -

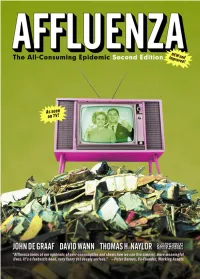

Affluenza: the All-Consuming Epidemic Second Edition

An Excerpt From Affluenza: The All-Consuming Epidemic Second Edition by John de Graaf, David Wann, & Thomas H. Naylor Published by Berrett-Koehler Publishers contents Foreword to the First Edition ix part two: causes 125 Foreword to the Second Edition xi 15. Original Sin 127 Preface xv 16. An Ounce of Prevention 133 Acknowledgments xxi 17. The Road Not Taken 139 18. An Emerging Epidemic 146 Introduction 1 19. The Age of Affluenza 153 20. Is There a (Real) Doctor in the House? 160 part one: symptoms 9 1. Shopping Fever 11 part three: treatment 2. A Rash of Bankruptcies 18 171 21. The Road to Recovery 173 3. Swollen Expectations 23 22. Bed Rest 177 4. Chronic Congestion 31 23. Aspirin and Chicken Soup 182 5. The Stress Of Excess 38 24. Fresh Air 188 6. Family Convulsions 47 25. The Right Medicine 197 7. Dilated Pupils 54 26. Back to Work 206 8. Community Chills 63 27. Vaccinations and Vitamins 214 9. An Ache for Meaning 72 28. Political Prescriptions 221 10. Social Scars 81 29. Annual Check-Ups 234 11. Resource Exhaustion 89 30. Healthy Again 242 12. Industrial Diarrhea 100 13. The Addictive Virus 109 Notes 248 14. Dissatisfaction Guaranteed 114 Bibliography and Sources 263 Index 276 About the Contributors 284 About Redefining Progress 286 vii preface As I write these words, a news story sits on my desk. It’s about a Czech supermodel named Petra Nemcova, who once graced the cover of Sports Illustrated’s swimsuit issue. Not long ago, she lived the high life that beauty bought her—jet-setting everywhere, wearing the finest clothes. -

Teacher's Guide

A 56 minute video In 2 parts for classrooms- 29/27 minutes Produced by John de Graaf and Vivia Boe A co-production of KCTS Seattle & Oregon Public Broadcasting Teacher’s Guide by Francine Strickwerda and Ti Locke AFFLUENZA will expose students to the problem of overconsumption and its effects on the society and the environment. The one-hour program takes a hard, sometimes humorous look at the American passion for shopping, and how it leads to debt and stress for families, communities, the nation and the world. It also explores the strategies used by marketers to sell products to young people. The program is appropriate for students grade 6-12, and in universities, and will be a useful resource for teachers of communications, economics, mathemat- ics, social studies, environmental studies and the arts. Each activity in this guide references a clip from the video, and discussion questions, which can be used before and after viewing the clip. Counters differ on VHS machines, so the starting and ending points for clips are approximate. Many activities also have background information and reproducible worksheets. CONTENTS Language Arts / Social Studies 3What is Affluenza? 5Worksheet- Family Interview Communications / Business / Economics 6 Activity #1 What are Advertisers really selling? 8 Activity #2 Who are advertisers selling to? 9 Activity #3 Advertising inSchools 10 Activity #4 Be an Adbuster Mathematics / Economics / Life Skills 12 #1 Credit Quandaries 15 Worksheet- Credit Cards: The Fine Print Social Studies / Environmental Studies 16 Activity #1 Popcorn Party 18 Activity #2 A Small World 20 Activity #3 A History of Wanting More 21 Worksheet - The Impact of Stuff Language Arts / Art 22 The Good Life References 23 Books 27 Organizations 31 Internet Quiz 32 What is Affluenza? 36 Do you have it? Bullfrog Films PO Box 149, Oley PA 19547 Phone: (610) 779-8226 or (800) 543-3764 Fax: (610) 370-1978 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bullfrogfilms.com © Copyright 1997. -

A Brief History of Frugality Discourses in the United States Terrence H

GCMC_A_479219.fm Page 235 Friday, July 16, 2010 8:41 PM Consumption Markets & Culture Vol. 13, No. 3, September 2010, 235–258 A brief history of frugality discourses in the United States Terrence H. Witkowski* 5 Department of Marketing, California State University, Long Beach, California, USA TaylorGCMC_A_479219.sgm10.1080/10253861003786975Consumption,1025-3866Original2010Taylor133000000SeptemberTerrenceWitkowskiwitko@csulb.edu and& Article Francis (print)/1477-223XFrancis Markets 2010 and Culture (online) Public discourses advocating frugal consumption have had a long history in the United States. This study provides a brief account of six different periods of such anti-consumerist thought and rhetoric: colonial, antebellum, Gilded Age, early 10 twentieth century, World War II, and late twentieth century. The final section uses history to better understand the religious, political, and societal tensions that have characterized American frugality discourses. Keywords: anti-consumption; frugality; thrift; US history 15 In the Fall of 2002, a small group of concerned Christians calling itself “The Evangel- ical Environmental Network” launched a media campaign built around the headline “What Would Jesus Drive?” An advertisement published on their website and in Christianity Today juxtaposed an image of Jesus at prayer with a photo of freeway 20 congestion (Figure 1). The copy attacked car pollution for the illness and death it causes – the elderly, poor, sick, and young being the most afflicted – and for its contribution to global warming. The appeal concluded as follows: Transportation is now a moral choice and an issue for Christian reflection. It’s about more than engineering – it’s about ethics. About obedience. About loving our neighbor. 25 So what would Jesus drive? We call upon America’s automobile industry to manufacture more fuel-efficient vehicles. -

Waving the Banana at Capitalism

Ethnography http://eth.sagepub.com/ 'Waving the banana' at capitalism: Political theater and social movement strategy among New York's 'freegan' dumpster divers Alex V. Barnard Ethnography 2011 12: 419 DOI: 10.1177/1466138110392453 The online version of this article can be found at: http://eth.sagepub.com/content/12/4/419 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Ethnography can be found at: Email Alerts: http://eth.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://eth.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://eth.sagepub.com/content/12/4/419.refs.html >> Version of Record - Nov 25, 2011 What is This? Downloaded from eth.sagepub.com at UNIV CALIFORNIA BERKELEY LIB on November 30, 2011 Article Ethnography 12(4) 419–444 ‘Waving the banana’ ! The Author(s) 2011 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav at capitalism: Political DOI: 10.1177/1466138110392453 theater and social eth.sagepub.com movement strategy among New York’s ‘freegan’ dumpster divers Alex V. Barnard University of California, Berkeley, USA Abstract This article presents an ethnographic study of ‘freegans’, individuals who use behaviors like dumpster diving for discarded food and voluntary unemployment to protest against environmental degradation and capitalism. While freegans often present their ideology as a totalizing lifestyle which impacts all aspects of their lives, in practice, freegans emphasize what would seem to be the most repellant aspect of their movement: eating wasted food. New Social Movement (NSM) theory would suggest that behaviors like dumpster diving are intended to assert difference and an alternative identity, rather than make more traditional social movement claims. -

The Wisdom of Frugality

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction For well over two thousand years frugality and simple liv- ing have been recommended and praised by people with a reputation for wisdom. Philosophers, prophets, saints, poets, culture critics, and just about anyone else with a claim to the title of “sage” seem generally to agree about this. Frugality and simplicity are praiseworthy; extrava- gance and luxury are suspect. This view is still widely promoted today. Each year new books appear urging us to live more economically, advising us how to spend less and save more, critiquing consumerism, or extolling the pleasures and benefits of the simple life.1 Websites and blogs devoted to frugality, simple living, downsizing, downshifting, or living slow are legion.2 The magazine Simple Living can be found at thou- sands of supermarket checkout counters. All these books, magazines, e- zines, websites, and blogs are full of good ideas and sound precepts. Some mainly offer advice regarding personal finance along with ingenious and useful money- saving tips. (The advice is usually excellent; the tips vary in value. I learned from For general queries, contact [email protected] 260966ZZI_WISDOM_CS6_PC.indd 1 30/06/2016 08:57:42 © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without -

2020 Gender Equality in the U.S

GENDER EQUALITY IN THE U.S. Assessing 500 leading companies on workplace equality including healthcare benefits SPECIAL REPORT DECEMBER 2020 Equileap is the leading organisation providing No part of this report may be reproduced data and insights on gender equality in the in any manner without the prior written corporate sector. permission of Equileap. Any commercial use of this material or any part of it will require We research and rank over 3,500 public a licence. Those wishing to commercialise companies around the world using a the use should contact Equileap at info@ unique and comprehensive Gender Equality equileap.com. ScorecardTM across 19 criteria, including the gender balance of the workforce, senior management and board of directors, as well as the pay gap and policies relating to parental leave and sexual harassment. This report was commissioned by the Tara Health Foundation. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................6 GENDER EQUALITY IN THE WORKPLACE.............................................................................7 Key Findings.......................................................................................................................................7 Top 25 Ranking...................................................................................................................................8 Category A / Gender balance in Leadership & Workforce........................................9 Category B / -

A Post-Keynesian Model of a Consumer-Led Transition

economies Article Downshifting in the Fast Lane: A Post-Keynesian Model of a Consumer-Led Transition Eric Kemp-Benedict * and Emily Ghosh Stockholm Environment Institute, US Center, Somerville, MA 02144, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-617-590-5436 Received: 6 December 2017; Accepted: 4 January 2018; Published: 10 January 2018 Abstract: If the world’s countries seriously tackle the climate targets agreed upon in Paris, their citizens are likely to experience substantial changes in production, consumption, and employment. We present a long-run post-Keynesian model for studying the potential implications of a major transition on macroeconomic stability and employment. It is a demand-led model in which firms have considerable but not absolute freedom to administer prices, while household consumption exhibits inertia. Firms continually seek input-saving technological improvements that, in aggregate, tie technological progress to firms’ cost structures. Together with firm pricing strategies and wage setting, the productivities of different inputs determine the functional income distribution. Saving and investment, and production and purchase of consumption goods, are undertaken by different economic actors, driven by income and capacity utilization, with the possibility that productive capacity exceeds, or falls short of, effective demand. The model produces business cycles and long waves driven by technological change. We present results for a “downshifting” scenario in which households voluntarily withdraw labor, and discuss the implications of downshifting for stability, growth, and employment. We contrast the downshifting scenario with ones in which households reduce consumption without withdrawing from the labor pool. Keywords: demand-led growth; downshifting; Kaleckian-Harrodian; post-Keynesian; ecological economics JEL Classification: E11; E12; O41; Q01; Q56 1.