The Material Life of Austin, Texas 1839-1846 Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Girl Scouts of Central Texas Explore Austin Patch Program

Girl Scouts of Central Texas Explore Austin Patch Program Created by the Cadette and Senior Girl Scout attendees of Zilker Day Camp 2003, Session 4. This patch program is a great program to be completed in conjunction with the new Capital Metro Patch Program available at gsctx.org/badges. PATCHES ARE AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE IN GSCTX SHOPS. Program Grade Level Requirements: • Daisy - Ambassador: explore a minimum of eight (8) places. Email [email protected] if you find any hidden gems that should be on this list and share your adventures here: gsctx.org/share EXPLORE 1. Austin Nature and Science Center, 2389 Stratford Dr., (512) 974-3888 2. *The Contemporary Austin – Laguna Gloria, 700 Congress Ave. (512) 453-5312 3. Austin City Limits – KLRU at 26th and Guadalupe 4. *Barton Springs Pool (512) 867-3080 5. BATS – Under Congress Street Bridge, at dusk from March through October. 6. *Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, 1800 Congress Ave. (512) 936-8746 7. Texas State Cemetery, 909 Navasota St. (512) 463-0605 8. *Deep Eddy Pool, 401 Deep Eddy. (512) 472-8546 9. Dinosaur Tracks at Zilker Botanical Gardens, 2220 Barton Springs Dr. (512) 477-8672 10. Elisabet Ney Museum, 304 E. 44th St. (512) 974-1625 11. *French Legation Museum, 802 San Marcos St. (512) 472-8180 12. Governor’s Mansion, 1010 Colorado St. (512) 463-5518 13. *Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, 4801 La Crosse Ave. (512) 232-0100 14. LBJ Library 15. UT Campus 16. Mayfield Park, 3505 W. 35th St. (512) 974-6797 17. Moonlight Tower, W. 9th St. -

1996-2015 Texas Book Festival Library Award Winners

1996-2015 Texas Book Festival Library Award Winners Abernathy Arlington Public Library, East Riverside Drive Branch Abernathy Public Library - 2000 Arlington Branch - 1996, 1997, Austin Public Library - 2004, 2007 Abilene 2001, 2008, 2014, 2015 Daniel H. Ruiz Branch Abilene Public Library – 1998, Arlington Public Library - 1997 Austin Public Library - 2001, 2006, 2009 Northeast Branch 2011 Abliene Public Library, South Arlington Public Library Southeast SE Austin Community Branch Branch - 1999 Branch Library - 2015 Austin Public Library - 2004 Alamo Arlington Public Library, Spicewood Springs Branch Lalo Arcaute Public Library - 2001 Woodland West Branch-2013 Albany George W. Hawkes Central Austin Public Library- 2009 Shackelford Co. Library - 1999, Library, Southwest Branch - St. John Branch Library 2004 2000, 2005, 2008, 2009 Austin Public Library - 1998, 2007 Alice Aspermont Terrazas Branch Alice Public Library - 2003 Stonewall Co. Public Library - Austin Public Library - 2007 Allen 1997 University Hills Branch Library Allen Public Library - 1996, 1997 Athens Austin Public Library - 2005 Alpine Henderson Co. Clint W. Murchison Windsor Park Branch Alpine Public Library – 1998, Memorial Library - 2000 Austin Public Library - 1999 2008, 2014 Aubrey Woodland West Branch Alpine Public Library South Aubrey Area Library - 1999 Cepeda Public Library - 2000, Branch - 2015 Austin 2006 Alto Austin Public Library - 1996, 2004 Lake Travis High - 1997 Stella Hill Memorial Library - Austin Public Library - 2004, 2007 School/Community Library 1998, -

Fall 2014 Newsletter

NEWSLETTER VOLUME 38 NO. 2 SEPTEMBER 2014 2013 CTA Fall Meeting, October 24, 2014 Business Meeting—Embassy Suites, 1001 E. McCarty Ln., San Marcos, TX 78666 CTA Careers in Archaeology Social—8:45 PM Agenda Registration – 8:30 AM New Business Call to Order – 9:00 AM The MAP—50th Anniversary of the NHPA Announcements Meeting Adjourns - 12:00 PM Approval of Minutes, Spring 2014 Meeting CTA Careers in Archaeology Social – 8:45 PM Officers’ Reports President (Missi Green) Past President (Rachel Feit) Secretary (Kristi Miller Nichols) A A Treasurer (Carole Leezer) A Newsletter Editor (Mindy Bonine) D D D Standing Committee Reports N N N Auditing (Mark Denton) E E CTA Communications (Mindy Bonine) E Contractors List (Shelly Fischbeck) G G Curation (Marybeth Tomka) G Governmental Affairs (Nesta Anderson) A A Multicultural Relations (Mary Jo Galindo) A Nominating (Bill Martin) Public Education (David Brown) Special Committee Reports Academic Archeology and CRM (Todd Ahlman) Anti-looting Committee (Jeffery Hanson) History (Doug Boyd) In this issue… Membership (Becky Shelton) Agency Reports President’s Forum ........................2 Texas Historical Commission (Pat Mercado- Map Embassy Suites San Marcos.3 Allinger) TAS Preliminary Schedule ............4 Texas Parks and Wildlife (Michael Strutt) Officer’s Reports...........................5 Texas Department of Transportation (Scott Announcements ...........................6 Pletka) Texas Archeological Research Laboratory Minutes (Spring 2014)..................7 (Jonathan Jarvis) 2014 Membership List..................12 Officers and Committee Chairs.....13 Old Business Join the CTA Yahoo! Group ..........14 Student Grant Applications Please renew your memberships! Membership Form........................15 1 CTA Newsletter 38(2) September 2014 President’s Forum By Missi Green chaeology Channel has also stepped up to par- ticipate. -

TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America

Capitol Area Council TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America TRAIL REQUIREMENTS: 1. There should be at least one adult for each 10 hikers. A group must have an adult leader at all times on the trail. The Boy Scouts of America policy requires two adult leaders on all Scout trips and tours. 2. Groups should stay together while on the hike. (Large groups may be divided into several groups.) 3. Upon completion of the trail the group leader should send an Application for Trail Awards with the required fee for each hiker to the Capitol Area Council Center. (Only one patch for each participant.) The awards will be mailed or furnished as requested by the group leader. Note: All of Part One must be hiked and all points (1-15) must be visited. Part Two is optional. HIKER REQUIREMENTS: 1. Any registered member of the Boy Scouts of America, Girl Scouts, or other civic youth group may hike the trail. 2. Meet all Trail requirements while on the hike. 3. The correct Scout uniform should be worn while on the trail. Some article (T-shirt, armband, etc) should identify other groups. 4. Each hiker must visit the historical sites, participate in all of his/her group’s activities, and answer the “On the Trail Quiz” to the satisfaction of his/her leader. Other places of interest you may wish to visit are: Zilker Park and Barton Springs Barton Springs Road Elisabet Ney Museum 304 E. 34th. Street Hike and Bike Trail along Town Lake Camp Mabry 38th. Street Lake Travis FM #620 Lake Austin FM # 2222 Capitol Area Council TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America ACCOMODATIONS: McKinney Falls State Park, 5805 McKinney Falls Parkway, Austin, TX 78744, tel. -

Hill Country Trail Region

Inset: Fredericksburg’s German heritage is displayed throughout the town; Background: Bluebonnets near Marble Falls ★ ★ ★ reen hills roll like waves to the horizon. Clear streams babble below rock cliffs. Wildfl owers blanket valleys in a full spectrum of color. Such scenic beauty stirs the spirit in the Texas Hill Country Trail Region. The area is rich in culture and mystique, from fl ourishing vineyards and delectable cuisines to charming small towns with a compelling blend of diversity in heritage and history. The region’s 19 counties form the hilly eastern half of the Edwards Plateau. The curving Balcones Escarpment defi nes the region’s eastern and southern boundaries. Granite outcroppings in the Llano Uplift mark its northern edge. The region includes two major cities, Austin and San Antonio, and dozens of captivating communities with historic downtowns. Millions of years ago, geologic forces uplifted the plateau, followed by eons of erosion that carved out hills more than 2,000 feet in elevation. Water fi ltered through limestone bedrock, shaping caverns and vast aquifers feeding into the many Hill Country region rivers that create a recreational paradise. Scenic beauty, Small–town charm TxDOT TxDOT Paleoindian hunter-gatherers roamed the region during prehistoric times. Water and wildlife later attracted Tonkawa, Apache and Comanche tribes, along with other nomads who hunted bison and antelope. Eighteenth-century Spanish soldiers and missionaries established a presidio and fi ve missions in San Antonio, which became the capital of Spanish Texas. Native American presence deterred settlements during the era when Texas was part of New Spain and, later, Mexico. -

Spring 2019 H Volume 23 No

SAVING THE GOOD STUFF Spring 2019 h Volume 23 No. 2 J oin us for “The Art of the Craftsman Style,” our 27th Annual 20th century. Creative updates show their seamless adaptation to Homes Tour! This year’s event celebrates seven stunning modern life today. Craftsman style homes citywide in coordination with the Harry Ransom Center exhibition The Rise of Everyday Design: The Arts This is Preservation Austin’s biggest event of the year, as well as our and Crafts Movement in Britain and America, on view now. most important fundraiser. Our members receive special pricing on tour During the late 19th century Britain’s Arts and Crafts Movement tickets and some membership levels include free tickets as well. We emphasized handmade domestic goods and honest design to hope you’ll join us, and bring along some friends, to spend a beautiful combat the more dehumanizing effects of the Industrial Revolution. Austin day celebrating these incredible homes, their homeowners, and Here in America, magazines and pattern books diffused the all the good work our nonprofit does year-round! h movement’s principles into the wildly-popular Craftsman style, embracing its picturesque aesthetic and democratic spirit to produce quality housing (albeit with machine-made components) Saturday, April 27 nationwide. 10am to 4pm Our tour explores the Arts and Crafts Movement’s impact here Home Base: Preservation Austin in Austin. Featured homes show a wide range of Craftsman style 500 Chicon, Texas Society of Architects Building influences, from pattern-book houses built by middle-and working- $30 for Preservation Austin Members class families to those designed by architects for families of more $40 for Non-Members means. -

African American Resource Guide

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE Sources of Information Relating to African Americans in Austin and Travis County Austin History Center Austin Public Library Originally Archived by Karen Riles Austin History Center Neighborhood Liaison 2016-2018 Archived by: LaToya Devezin, C.A. African American Community Archivist 2018-2020 Archived by: kYmberly Keeton, M.L.S., C.A., 2018-2020 African American Community Archivist & Librarian Shukri Shukri Bana, Graduate Student Fellow Masters in Women and Gender Studies at UT Austin Ashley Charles, Undergraduate Student Fellow Black Studies Department, University of Texas at Austin The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use. INTRODUCTION The collections of the Austin History Center contain valuable materials about Austin’s African American communities, although there is much that remains to be documented. The materials in this bibliography are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This bibliography is one in a series of updates of the original 1979 bibliography. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals and support groups. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the online computer catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing collection holdings by author, title, and subject. These entries, although indexing ended in the 1990s, lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be time-consuming to find and could be easily overlooked. -

Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL and GEOLOGICAL WONDERS

Iid Guide AUSTIN2015/2016 Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL AND GEOLOGICAL WONDERS TUNE IN: ESSENTIAL YOUR GUIDE TO AUSTIN’S NEARBY GEMS: PERFECT MUSIC EXPERIENCES NEIGHBORHOODS HILL COUNTRY ROAD TRIPS PAGE 10 PAGE 15 PAGE 45 WE DITCHED THE LANDSCAPES FOR MORE SOUNDSCAPES. If you’re going to spend some time in Austin, shouldn’t you stay in a suite that feels like it’s actually in Austin? EXPLORE OUR REINVENTION at Radisson.com/AustinTX AUSTIN CONVENTION & VISITORS BUREAU 111 Congress Ave., Suite 700, Austin, TX 78701 800-926-2282, Fax: 512-583-7282, www.austintexas.org President & CEO Robert M. Lander Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Julie Chase Director of Marketing Communications Jennifer Walker Director of Digital Marketing Katie Cook Director of Content & Publishing Susan Richardson Director of Austin Film Commission Brian Gannon Senior Communications Manager Shilpa Bakre Tourism & PR Manager Lourdes Gomez Film, Music & Marketing Coordinator Kristen Maurel Marketing & Tourism Coordinator Rebekah Grmela AUSTIN VISITOR CENTER 602 E. Fourth St., Austin, TX 78701 866-GO-AUSTIN, 512-478-0098 Hours: Mon. – Sat. 9 a.m. – 5 p.m., Sun. 10 a.m.– 5 p.m. Director of Retail and Visitor Services Cheri Winterrowd Visitor Center Staff Erin Bevins, Harrison Eppright, Tracy Flynn, Patsy Stephenson, Spencer Streetman, Cynthia Trenckmann PUBLISHED BY MILES www.milespartnership.com Sales Office: P.O. Box 42253, Austin, TX 78704 512-432-5470, Fax: 512-857-0137 National Sales: 303-867-8236 Corporate Office: 800-303-9328 PUBLICATION TEAM Account Director Rachael Root Publication Editor Lisa Blake Art Director Kelly Ruhland Ad & Data Manager Hanna Berglund Account Executives Daja Gegen, Susan Richardson Contributing Writers Amy Gabriel, Laura Mier, Kelly Stocker SUPPORT AND LEADERSHIP Chief Executive Officer/President Roger Miles Chief Financial Officer Dianne Gates Chief Operating Officer David Burgess For advertising inquiries, please contact Daja Gegen at [email protected]. -

Muffled Voices of the Past: History, Mental Health, and HIPAA

INTERSECT: PERSPECTIVES IN TEXAS PUBLIC HISTORY 27 Muffled Voices of the Past: History, Mental Health, and HIPAA by Todd Richardson As I set out to write this article, I wanted to explore mental health and the devastating toll that mental illness can take on families and communities. Born out of my own personal experiences with my family, I set out to find historical examples of other people who also struggled to find treatment for themselves or for their loved ones. I know that when a family member receives a diagnosis of a chronic mental illness, their life changes drastically. Mental illness affects individuals and their loved ones in a variety of ways and is a grueling experience for all parties involved. When a family member’s mind crumbles, often that person— the brother or father or favorite aunt— is gone forever. Families, left helpless, watch while a person they care for exists in a state of constant anguish. I understood that my experiences were neither new nor unique. As a student of history, I knew that other families’ stories must exist somewhere in the recorded past. By looking back through time, I hoped to shine a light on the history of American mental health policy and perhaps to make the voices of those affected by mental illness heard. Doing so might bring some sense of justice and awareness to the lives of people with mental illness in the present in the same way that history allows other marginalized groups to make their voices heard and reshape the way people perceive the past. -

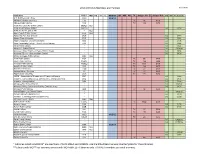

2019-20 MALA Members and Partners * Libraries Noted As MOBIUS* Are

2019-20 MALA Members and Partners 10/2/2019 Institution OCLC MO KS IA IL MOBIUS AR NM OK TX Amigos Site ID Amigos Hub CO WY CLiC Code A.T. Still Memorial Library WG1 MOBIUS Abilene Christian University TXC TX 36 WTX Abilene Public Library TXB TX 155 WTX Academie Lafayette School Library MOALC MO Academy 20 School District COPCH CO C314 Academy for Integrated Arts * MO Adair County Public Library KVA MO Adams 12 Five Star Schools DVA CO C878 Adams State University CLZ CO C384 Adams-Arapahoe 28J School District XN0 CO C108 Aims Community College - Jerry A. Kiefer Library CAA CO C884 Akron Public Library * CO C824 Akron R-1 School District * CO C824.as Alamosa Library (Southern Peaks Public Library) * CO C404 Alamosa RE-11J - Alamosa High School * CO C406 Albany Carnegie Public Library MQ2 MO Allen Public Library TOP TX 95 DFW Alpine Public Library TXAPL TX 122 HKB Alvarado Public Library TXADO TX 8801 DFW Amarillo Public Library TAP TX 156 WTX Amberton University TAM TX 27 DFW Amigos Library Services IIC TX 23 DFW Angelo State University ANG TX 19 WTX AORN - Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses DNF CO C886 Arapahoe Community College Library and Learning Commons DVZ CO C874 Arapahoe Library District CO2 CO C214 Arickaree R-2 School District * CO C840.ar Arkansas Valley Correctional Facility General Library * CO C402 Arlington Public Library AR9 TX 98 DFW Arriba-Flagler C-20 School District * CO C836.af Arrowhead Correctional Center * CO C370 Assistive Technology Partners (SWAAAC) * CO C209 Atchison County Library MQ3 MO Aubrey -

Mexican American Resource Guide: Sources of Information Relating to the Mexican American Community in Austin and Travis County

MEXICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE: SOURCES OF INFORMATION RELATING TO THE MEXICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY IN AUSTIN AND TRAVIS COUNTY THE AUSTIN HISTORY CENTER, AUSTIN PUBLIC LIBRARY Updated by Amanda Jasso Mexican American Community Archivist September 2017 Austin History Center- Mexican American Resource Guide – September 2017 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use so that customers can learn from the community’s collective memory. The collections of the AHC contain valuable materials about Austin and Travis County’s Mexican American communities. The materials in the resource guide are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This guide is one of a series of updates to the original 1977 version compiled by Austin History staff. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals, support groups and Austin History Center staff. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the Find It: Austin Public Library On-Line Library Catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing individual items in the collection with entries under author, title, and subject. These tools lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be very difficult to find. It must be noted that there are still significant gaps remaining in our collection in regards to the Mexican American community. -

Places to Visit in GSCTX Tip Sheet

Places To Visit in GSCTX Tip Sheet Location City Area County The Eckert James River Bat Cave Preserve Mason 1 Mason Fort Mason, a Texas Frontier Fort Mason 1 Mason Topaz Hunting (Seaquist Ranch, Lindsay Ranch, Bar M Ranch) Mason 1 Mason Fort Concho San Angelo 1 Tom Green International Lilly Collection San Angelo 1 Tom Green San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts San Angelo 1 Tom Green Sheep Tour San Angelo 1 Tom Green Cameron Park Zoo Waco 2 McLennan Dr. Pepper Museum Waco 2 McLennan Mayborn Museum Waco 2 McLennan Texas Ranger Museum Waco 2 McLennan Waco Mammoth National Monument Waco 2 McLennan Blue Baker Bakery Tour College Station 3 Brazos George W. Bush Presidential Library College Station 3 Brazos The Jersey Barnyard La Grange 3 Fayette Texas Renaissance Festival Todd Mission 3 Grimes Blue Bell Creameries Brenham 3 Washington Brenham Miniature Horses Brenham 3 Washington Burton Cotton Gin & Museum Burton 3 Washington Peeka Ranch - Alpacas Burton 3 Washington Washington-on-the Brazos State Historic Site Washington 3 Washington Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park Johnson City 4 Blanco Pedernales Falls State Park Johnson City 4 Blanco Eagle Eye Observatory Burnet 4 Burnet Longhorn Caverns Burnet 4 Burnet Eugene Clarke Library Lockhart 4 Caldwell Chisholm Wolf Foundation Dale 4 Caldwell Enchanted Rock Fredericksburg 4 Gillespie Museum of the Pacific War Fredericksburg 4 Gillespie Lyndon B. Johnson Ranch Stonewall 4 Gillespie Aquarena Center San Marcos 4 Hays Wonder World Cave & Wildlife Park San Marcos 4 Hays Hamilton Pool Preserve Dripping