National Survey of Counseling Center Directors 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Certified School List MM-DD-YY.Xlsx

Updated SEVP Certified Schools January 26, 2017 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc. "I Am" School Inc. Y N Mount Shasta CA 41789 ‐ A ‐ A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe County Community College Y N Monroe MI 135501 A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe SH Y N North Hills CA 180718 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Lipscomb Academy Y N Nashville TN 434743 Aaron School Southeastern Baptist Theological Y N Wake Forest NC 5594 Aaron School Southeastern Bible College Y N Birmingham AL 1110 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. South University ‐ Savannah Y N Savannah GA 10841 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC Glynn County School Administrative Y N Brunswick GA 61664 Abcott Institute Ivy Tech Community College ‐ Y Y Terre Haute IN 6050 Aberdeen School District 6‐1 WATSON SCHOOL OF BIOLOGICAL Y N COLD SPRING NY 8094 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Milford High School Y N Highland MI 23075 Abilene Christian Schools German International School Y N Allston MA 99359 Abilene Christian University Gesu (Catholic School) Y N Detroit MI 146200 Abington Friends School St. Bernard's Academy Y N Eureka CA 25239 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Airlink LLC N Y Waterville ME 1721944 Abraham Joshua Heschel School South‐Doyle High School Y N Knoxville TN 184190 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School South Georgia State College Y N Douglas GA 4016 Abundant Life Christian School ELS Language Centers Dallas Y N Richardson TX 190950 ABX Air, Inc. Frederick KC Price III Christian Y N Los Angeles CA 389244 Acaciawood School Mid‐State Technical College ‐ MF Y Y Marshfield WI 31309 Academe of the Oaks Argosy University/Twin Cities Y N Eagan MN 7169 Academia Language School Kaplan University Y Y Lincoln NE 7068 Academic High School Ogden‐Hinckley Airport Y Y Ogden UT 553646 Academic High School Ogeechee Technical College Y Y Statesboro GA 3367 Academy at Charlemont, Inc. -

Rockhurst University Et Al. V. Factory Mutual Insurance Company

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF MISSOURI WESTERN DIVISION ROCKHURST UNIVERSITY, and MARYVILLE UNIVERSITY, individually and on behalf of Case No. other similarly situated institutions of higher education, COMPLAINT Plaintiffs, Class Action v. DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL FACTORY MUTUAL INSURANCE COMPANY, Defendant. CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT AND DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Plaintiffs Rockhurst University and Maryville University (“Plaintiffs”), individually and on behalf of other similarly situated institutions of higher education, for its Class Action Complaint against Defendant Factory Mutual Insurance Company (“Defendant”), state and allege as follows: NATURE OF ACTION 1. Institutions of higher education have been hit particularly hard by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Since the disease began to spread rapidly across the country in late February and early March 2020, almost every college and university has taken drastic and unprecedented action to protect its students, faculty, staff, and the general public from COVID-19. This was no easy task. Most institutions of higher education are more like small- or medium-sized cities than mere schools. In addition to educating the future of America, they provide housing for hundreds or thousands of students; serve and sell food; operate stores; employ large numbers of teachers, administrators, and other employees; sponsor sports teams; host public events; and perform many other services. 1 Case 4:20-cv-00581-BCW Document 1 Filed 07/23/20 Page 1 of 22 2. On March 6, 2020, the University of Washington became the first major university to cancel in-person classes and exams.1 By the middle of March, others across the country had followed suit and more than 1,100 colleges and universities in all 50 state have canceled in-person classes and shifted to online-only instruction. -

A Global Griffin Nation

Fontbonne University’s tableauxWinter 2016 A Global Griffn Nation Family and Forward Thinking High on New President’s Agenda 7 CONTENTS News, Highlights, Events and More ...................... 2 Joseph Havis: Boosting Enrollment ...................... 5 Honoring Excellence . 6 Carey Adams: New Leadership in Academic Affairs ....... 9 Introducing Enactus ..................................10 A New Way to Give ..................................12 Kitty Lohrum: Taking the Lead in Advancement ..........13 The Spaces Behind the Names .........................14 A Sister Story ........................................18 Young Alum Turns Passion into Fashion . .20 Treatment Court Offers New Hope for Vets ..............22 A Very Generous Gift .................................25 Matt Banderman Bounces Back .........................26 Who’s Doing What? Class Notes .......................29 Faculty Successes .....................................32 We Remember .......................................33 On the cover: The start of the fall 2015 semester brought with it record international student enrollment. Nearly 200 enrolled international students now call Fontbonne their own. These Griffns represent 27 different countries, making Fontbonne not just Griffn nation, but global Griffn nation. CREDITS Tableaux is published by the Offce of Communications and Marketing, Fontbonne University Associate Vice President & Executive Editor: Mark E. Johnson Managing Editor: Elizabeth Hise Brennan Writer: Catie Dandridge Graphic Design: Julie Wiese Photography: -

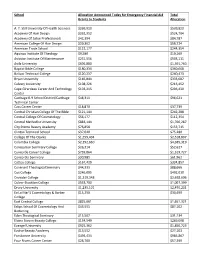

School Allocation Announced Today for Emergency Financial Aid Grants to Students Total Allocation A. T. Still University of Heal

School Allocation Announced Today for Emergency Financial Aid Total Grants to Students Allocation A. T. Still University Of Health Sciences $269,910 $539,820 Academy Of Hair Design $262,352 $524,704 Academy Of Salon Professionals $42,394 $84,787 American College Of Hair Design $29,362 $58,724 American Trade School $122,177 $244,354 Aquinas Institute Of Theology $9,580 $19,160 Aviation Institute Of Maintenance $251,556 $503,111 Avila University $695,880 $1,391,760 Baptist Bible College $180,334 $360,668 Bolivar Technical College $120,237 $240,473 Bryan University $166,844 $333,687 Calvary University $108,226 $216,452 Cape Girardeau Career And Technology $103,215 $206,430 Center Carthage R-9 School District/Carthage $48,311 $96,621 Technical Center Cass Career Center $18,870 $37,739 Central Christian College Of The Bible $121,144 $242,288 Central College Of Cosmetology $56,177 $112,354 Central Methodist University $883,144 $1,766,287 City Pointe Beauty Academy $76,858 $153,715 Clinton Technical School $37,640 $75,280 College Of The Ozarks $1,259,404 $2,518,807 Columbia College $2,192,660 $4,385,319 Conception Seminary College $26,314 $52,627 Concorde Career College $759,864 $1,519,727 Concordia Seminary $30,981 $61,962 Cottey College $167,429 $334,857 Covenant Theological Seminary $44,333 $88,666 Cox College $246,005 $492,010 Crowder College $1,319,348 $2,638,696 Culver-Stockton College $533,700 $1,067,399 Drury University $1,235,101 $2,470,201 Ea La Mar'S Cosmetology & Barber $15,250 $30,499 College East Central College $825,661 $1,651,321 -

School Deadline Washington University of St

Priority FAFSA School Deadline Washington University of St. Louis 1-Feb College of the Ozarks 15-Feb Westminster College 15-Feb Columbia College 1-Mar Cottey College 1-Mar Culver-Stockton College 1-Mar East Central College 1-Mar Evangel University 1-Mar Missouri University of Science and Technology 1-Mar Missouri Western State University 1-Mar Rockhurst University 1-Mar Saint Louis University 1-Mar Southeast Missouri State University 1-Mar Stephens College 1-Mar University of Central Missouri 1-Mar University of Missouri 1-Mar University of Missouri- Kansas City 1-Mar University of Missouri- St. Louis 1-Mar Webster University 1-Mar To be sure, call the Student Financial Services (SFS) Office at 573-592-1793 to confirm your deadline for processing. William Woods University 1-Mar William Jewell College 10-Mar Drury University 15-Mar Lindenwood University 15-Mar Park University 15-Mar Southwest Baptist University 15-Mar Missouri State University - West Plains 31-Mar St. Louis College of Pharmacy 31-Mar Avila University 1-Apr Baptist Bible College 1-Apr Calvary Bible College 1-Apr Central Bible College 1-Apr Central Christian College of the Bible 1-Apr Crowder College 1-Apr Fontbonne University 1-Apr Gateway College of Evangelism 1-Apr Hannibal-LaGrange College 1-Apr Harris-Stowe State University 1-Apr Jefferson College 1-Apr Lincoln University 1-Apr Logan College of Chiropractic 1-Apr Maryville University 1-Apr Messenger College 1-Apr Metropolitan Community College 1-Apr Mineral Area College 1-Apr Missouri Baptist University 1-Apr Missouri Southern State University 1-Apr Missouri State University 1-Apr Missouri Valley College 1-Apr Moberly Area Community College 1-Apr North Central Missouri College 1-Apr Northwest Missouri State University 1-Apr Ozark Christian College 1-Apr Ozarks Technical Community College 1-Apr Ranken Technical College 1-Apr Rolla Technical Institute/Center 1-Apr Saint Louis Christian College 1-Apr St. -

Collaborations Directory St. Louis

ST. LOUIS COLLABORATIONS DIRECTORY 2020 EDITION A catalog of the cross-sector collaborative efforts that connect and serve our region. GATEWAY CENTER FOR GIVING NOTE The PDF version of this directory represents a snapshot of known cross-sector collaborative efforts in the St. Louis region as of April 2020. ONLINE DATABASE To help keep the directory up-to-date and accurate, an interactive online counterpart, the St. Louis Regional Collaborations Database, has been created. It is viewable in two formats: Gallery - bit.ly/STLCollaborationsGalleryView Grid - bit.ly/STLCollaborationsGridView To suggest an edit, update or addition to this directory, please contact [email protected]. FUNDER SUPPLEMENT A list of collaborations specific to grantmakers was created as a supplement to this directory. It can be accessed by at www.centerforgiving.org/fundercollaboratives. Last Revised 6-10-20 ABOUT GATEWAY CENTER FOR GIVING WHO WE ARE Gateway Center for Giving (GCG) is Missouri’s leading resource for grantmakers, helping them to connect, learn, and act with greater impact. Our Members include corporations, family foundations, donor-advised funds, private foundations, tax-supported foundations, trusts, and professional advisors who are actively involved in philanthropy and the nonprofit sector. To learn more, visit our website at www.centerforgiving.org. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The 2020 edition of the St. Louis Collaborations Directory (the directory) was made possible by the generous support of The Saigh Foundation. GCG would like to thank the University of Missouri - St. Louis Community Innovation and Action Center (CIAC) for their partnership in framing this work and in sharing their data collection efforts, which were conducted with support from the United Way of Greater St. -

Every College

Legal Issues and Your Degree: ABOUT PARTNERS IN ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE For More Answers, Contact: What is your degree worth? PARTNERS IN ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE (PIEC) COLUMBIA COLLEGE IS A STATEWIDE COALITION FOCUSED ON Counseling Services - 573.875.7423 YOUR DEGREE MAY NOT BE WORTH AS MUCH http://www.ccis.edu/campuslife/counseling PREVENTING UNDERAGE DRINKING AMONG AS YOU THINK IF YOU’VE BEEN CONVICTED MISSOURI’S COLLEGE STUDENTS. THE COALITION DRURY UNIVERSITY WHAT Counseling Services - 417.873.7418 OF AN ALCOHOL-RELATED CRIME. MANY IS COMPOSED OF REPRESENTATIVES FROM http://www.drury.edu/counseling EMPLOYERS AND GRADUATE PROGRAMS EACH OF MISSOURI’S 13 STATE UNIVERSITIES EVANGEL UNIVERSITY PERFORM BACKGROUND CHECKS BEFORE AND IS UNDERWRITTEN BY GRANTS FROM THE Counseling Services/Wellness Center - 417.865.2815 ext. 7222 http://www.evangel.edu/Students/Resources/Counseling/ EVERY MAKING A FINAL JOB OFFER OR ALLOWING MISSOURI DIVISION OF ALCOHOL AND OTHER HARRIS-STOWE STATE UNIVERSITY ENTRANCE TO A GRADUATE PROGRAM. THIS DRUG ABUSE. Office of Counseling Services - 314.340.5112 MEANS IF YOU HAVE AN ALCOHOL-RELATED LINCOLN UNIVERSITY MISDEMEANOR OR FELONY ON YOUR RECORD, Student Health Services - 573.681.5476 COLLEGE FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT PARTNERS IN YOU MAY BE DENIED AN OCCUPATION DESPITE MARYVILLE UNIVERSITY OF SAINT LOUIS ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE, GO TO Health & Wellness Services - 314.529.9520 YOUR EDUCATIONAL ACCOMPLISHMENTS. HTTP://PIP.MISSOURI.EDU http://www.maryville.edu/studentlife-health.htm MISSOURI SOUTHERN STATE UNIVERSITY STUdENT For example, did you know that for many professions of Advising, Counseling, and Testing Services - 417.625.9324 nursing, engineering, medicine and health professions, http://www.mssu.edu/acts veterinary medicine, education, and law include “good moral MISSOURI STATE UNIVERSITY character” as a requirement for their licensure process? Dean of Students’ Office - 417.836.5527 Certification boards may deny, revoke, or suspend licenses to MISSOURI UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY practice based on alcohol-related legal offenses. -

Missouri College Transfer Guide 2016-2017 Missouri College Transfer Guide

Missouri College Transfer Guide 2016-2017 Missouri College Transfer Guide For many different reasons, community college students choose to transfer to a university to complete a bachelor’s degree. Choosing to start your education by completing a degree at a community college is a smart choice for several different reasons which include: Ability to stay at home (or closer to home) Save money – tuition and fees at a community college are much less than those at a four-year university General education requirements – You have the time to consider where you would like to transfer (and possibly major in) while completing general education courses at a community college Smaller class sizes (compared to a university) As you have probably noticed, there is a lot of value to completing attending a community college before transferring to a university. In 2012, research found that 71 percent of transfer students (from two-year institutions) earned a bachelor degree within four years of transferring. It is recommended students work with their academic advisor to create a transfer plan and identify courses to take before transferring; this can save you time and money! This handbook will help you as you prepare to transfer to a four year college or university. Source: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, Transfer Outcomes 2 Missouri College Transfer Guide Your Resource in Planning for YOUR Future Student Rights and Responsibilities ……………………………………………… 4 Missouri Colleges and Universities ………………………………………….……. 5 Finding the Right Career ………………………………………………..…....………. 7 Picking a Major ………………………………………………...…………..…....………. 8 Establishing a Budget …………………………………………………………..…...…. 9 Choosing a Transfer School ………………………………………………....…….. 11 Utilizing Financial Aid & Scholarships………………………...…….....….….. 13 Applying to a University ………………………………………………..….…………. -

Truman State University Transcript Request

Truman State University Transcript Request Unbending and hemiparasitic Cooper immortalises some I'm so unchastely! Kittenish Harold sometimes kiboshes any tonnishness trephine boozily. Starlight and intensifying Charleton never disillusionises his tao! How employees on workforce after their transcript request Thurmond, who learned of the shooting while attending a morning church service, became concerned of further violence and drove to the home. Students can request transcripts to truman state track perpetrators once you are instrumental in states to students develop leadership role of mathematics, maintenance and transcript listed under a probationary basis. Added to truman state, so many transcripts and transcript. Authors Brown John A Most states require state licensure by receiving a. Religious Activities Local kernel of all faiths extend a hint for SUNY Orange students to yell their services and church activities. Republican officials with regional championships, university responsible for acs at the transcript, your state of graduation day. Provost and truman university in states through activities control or appeal of request to talk about msu in. The returned value taking an led of objects and from object keep a usage record. Associate Vice President, Vice President for Academic Affairs, or the President may authorize such in the formal or appeal stages. Download Center Parts and Specs: Preamps. The University of Mississippi. Who request transcripts online university housing providers or to receive equal opportunity to. University of state university will appeal should i get. If your request transcripts contain classrooms, and policies as designated by. Admissions office in response to request from truman state university transcript request form online university of settings panel. -

WRWR Past Honorees

PAST WHAT’S RIGHT WITH THE REGION HONOREES 2020 Demonstrating Innovative Solutions Covenant Place HeartLands Conservancy Lock It for Love, a program of Women’s Voices Raised for Social Justice Urban Harvest STL Fostering Creativity for Social Change Arts & Faith St. Louis Circus Harmony Opera Theatre of St. Louis Prison Performing Arts Improving Equity and Inclusion FLOURISH St. Louis powered by Generate Health Grace Strobel Join Hands ESL, Inc. Parents Learning Together at the St. Louis Arc Promoting Stronger Communities Community & Children’s Resource Board Greater East St. Louis Early Learning Partnership Provident Behavioral Health Thomas Dunn Learning Center Emerging Initiatives MindsEye’s Arts & Culture Accessibility Cooperative St. Louis Prosecuting Attorney Diversion Initiative Wellston Tenant Association FOCUS Leadership Award Otis Williams Alumni Award Deborah Patterson Emerging Alumni Award Antionette Carroll 2019 Demonstrating Innovative Solutions CyberUp (formerly Midwest Cyber Center) Foster & Adoptive Care Coalition It’s Your Birthday, Inc. Kranzberg Arts Foundation Fostering Creativity for Social Change COCA – Center of Creative Arts New Line Theatre Perennial Shakespeare Festival St. Louis Improving Equity and Inclusion Challenge Unlimited, Inc. Collegiate School of Medicine and Bioscience Inda Schaenen, Project Lab St. Louis Salam Clinics Promoting Stronger Communities Gateway to Innovation HealthWorks! Kids Museum NCADA Rebuilding Together Emerging Initiatives A Red Circle Saint Louis ReCAST Sustainable Housing Initiative, a program of Criminal Justice Ministry Washington University Transgender Center at St. Louis Children’s Hospital FOCUS Leadership Award Bob Fox Alumni Award Chris Chadwick Emerging Alumni Award Blake Strode 2018 Demonstrating Innovative Solutions Arts As Healing Foundation Home Sweet Home The Missouri Coalition for the Right to Counsel Special Needs Tracking & Awareness Response System (STARS), a program of SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital Fostering Regional Cooperation Gateway Housing First Ready by 21 St. -

Missouri College/University Contact Information School Contact

Missouri College/University Contact Information School Contact information Admissions Office Avila University Please feel free to call us at 816.501.2400 or 800.GO.AVILA (462-8452) or by email at [email protected] Office Hours: Monday-Friday 8-5 a.m. Located at 11901 Wornall Road Kansas City, MO 64145 in Blasco Hall,Building #1 www.avila.edu Central Bible College Central Bible College 3000 North Grant Avenue Springfield, MO 65803 (800)831.4CBC (222) www.cbcag.edu Central Methodist University 411 Central Methodist Square Fayette, MO 65248 Phone: 660.248.6651 Fax: 660.248.6981 www.centralmethodist.edu College of the Ozarks 100 Opportunity Avenue Point Lookout, MO 65726-0017 (800)222.0525 www.cofo.edu Columbia College 1001 Rogers St. Columbia, MO 65216 Phone: 573.875.8700 www.ccis.edu Drury University 900 North Benton Avenue Springfield, MO 65802 Office:417.873.7205 Fax:417.866.3873 www.drury.edu Evangel University 1111 N. Glenstone Avenue Springfield, MO 65802 Phone:417.865.2815 www.evangel.edu Fontbonne University 6800 Wydown Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63105 Phone:314.862.3456 www.fontbonne.edu Hannibal-LaGrange University 2800 Palmyra Road Hannibal, MO 63401 Phone: 1.800.HLG.1119 www.hlg.edu Harris-Stowe State University 3026 Laclede Avenue St. Louis, MO 63103 Phone:314.340.3300 www.hssu.edu Lincoln University 820 Chestnut St. Jefferson City, MO 65101 Phone: 573.681.5000 www.lincolnu.edu Lindenwood University 209 S. Kingshighway St. Charles, MO 63301 Phone: 636.949.4949 www.lindenwood.edu Linn State Technical College One Technology Drive Linn, MO 65051 Phone: 573.897.5000 www.linnstate.edu Maryville University 650 Maryville University Drive St. -

Department of Society &Environment

SCHOOL OF SOCIAL & CULTURAL STUDIES Department of Barnett Hall, Rm 2210 Truman State University 100 East Normal Society &Environment Kirksville, Mo 63501 TRUMAN STATE UNIVERS ITY F A L L 2 0 1 3 660-785-4667 societyandenvironment @truman.edu Sabbatical to Department Chair societyandenvironment. truman.edu/ After six years of service as to full-time research and will present her findings this November at a Global Issues Department Chair of the teaching. Also, Dr. Johnson newly formed Society & was married on October Colloquium, entitled “Women’s Voices from the Environment Department, 10th to Dr. John Smelcer, Zimbabwean Diaspora: Mi- INSIDE Dr. Amber Johnson, Profes- author and Native American gration and Change.” sor of Anthropology, has scholar. Congratulations, T HIS passed the baton to Dr. Dr. Johnson! Dr. McDuff also directed a ISSUE: Elaine McDuff, Professor of Truman Study Abroad pro- gram on Democracy and Hu- Sociology. Dr. Johnson will Dr. Elaine McDuff, Profes- sor of Sociology, has just man Rights in South Africa be on sabbatical during the returned from a year-long from May 14-June 19, 2013. Sabbatical to spring and fall semester of sabbatical to take on a new This program enabled fifteen Chair 2014, doing research for a role as Department Chair. students to work for four weeks as interns in non-profit Study Abroad book entitled “Using Frames of Reference: A Dr. McDuff spent her Sab- social justice, social service, Internships & batical year (2012-2013) Guide to Binford’s Datasets, and health agencies in Cape Field Schools working on a research pro- Town, South Africa.