Rhode Island M Edical J Ournal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predictive QSAR Tools to Aid in Early Process Development of Monoclonal Antibodies

Predictive QSAR tools to aid in early process development of monoclonal antibodies John Micael Andreas Karlberg Published work submitted to Newcastle University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Engineering November 2019 Abstract Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have become one of the fastest growing markets for diagnostic and therapeutic treatments over the last 30 years with a global sales revenue around $89 billion reported in 2017. A popular framework widely used in pharmaceutical industries for designing manufacturing processes for mAbs is Quality by Design (QbD) due to providing a structured and systematic approach in investigation and screening process parameters that might influence the product quality. However, due to the large number of product quality attributes (CQAs) and process parameters that exist in an mAb process platform, extensive investigation is needed to characterise their impact on the product quality which makes the process development costly and time consuming. There is thus an urgent need for methods and tools that can be used for early risk-based selection of critical product properties and process factors to reduce the number of potential factors that have to be investigated, thereby aiding in speeding up the process development and reduce costs. In this study, a framework for predictive model development based on Quantitative Structure- Activity Relationship (QSAR) modelling was developed to link structural features and properties of mAbs to Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) retention times and expressed mAb yield from HEK cells. Model development was based on a structured approach for incremental model refinement and evaluation that aided in increasing model performance until becoming acceptable in accordance to the OECD guidelines for QSAR models. -

Study Protocol

PROTOCOL SYNOPSIS A Multicentre, Randomised, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Phase 3 Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Two Doses of Anifrolumab in Adult Subjects with Active Systemic Lupus Erythematosus International Coordinating Investigator Study site(s) and number of subjects planned Approximately 450 subjects are planned at approximately 173 sites. Study period Phase of development Estimated date of first subject enrolled Q2 2015 3 Estimated date of last subject completed Q2 2018 Study design This is a Phase 3, multicentre, multinational, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of an intravenous treatment regimen of anifrolumab (150 mg or 300 mg) versus placebo in subjects with moderately to severely active, autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) while receiving standard of care (SOC) treatment. The study will be performed in adult subjects aged 18 to 70 years of age. Approximately 450 subjects receiving SOC treatment will be randomised in a 1:2:2 ratio to receive a fixed intravenous dose of 150 mg anifrolumab, 300 mg anifrolumab, or placebo every 4 weeks (Q4W) for a total of 13 doses (Week 0 to Week 48), with the primary endpoint evaluated at the Week 52 visit. Investigational product will be administered as an intravenous (IV) infusion via an infusion pump over a minimum of 30 minutes, Q4W. Subjects must be taking either 1 or any combination of the following: oral corticosteroids (OCS), antimalarial, and/or immunosuppressants. Randomisation will be stratified using the following factors: SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) score at screening (<10 points versus ≥10 points); Week 0 (Day 1) OCS dose 2(125) Revised Clinical Study Protocol Drug Substance Anifrolumab (MEDI-546) Study Code D3461C00005 Edition Number 5 Date 18 May 2016 (<10 mg/day versus ≥10 mg/day prednisone or equivalent); and results of a type 1 interferon (IFN) test (high versus low). -

New Treatments for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus on the Horizon: Targeting Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells to Inhibit Cytokine Production Laura M

C al & ellu ic la n r li Im C m Journal of Clinical & Cellular f u o Davison and Jorgensen et al., J Clin Cell Immunol n l o a l n o 2017, 8:6 r g u y o J Immunology DOI: 10.4172/2155-9899.1000534 ISSN: 2155-9899 Commentary Open Access New Treatments for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus on the Horizon: Targeting Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells to Inhibit Cytokine Production Laura M. Davison and Trine N. Jorgensen* Department of Immunology, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio, USA *Corresponding author: Dr. Trine N. Jorgensen, Department of Immunology, NE40, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Ohio, USA, Phone: +1 216-444-7454; Fax: +1 216-444-9329; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: December 4, 2017; Accepted date: December 13, 2017; Published date: December 20, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Davison LM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) often have elevated levels of type I interferon (IFN, particularly IFNα), a cytokine that can drive many of the symptoms associated with this autoimmune disorder. Additionally, the presence of autoantibody-secreting plasma cells contributes to the systemic inflammation observed in SLE and IFNα supports the survival of these cells. Current therapies for SLE are limited to broad immunosuppression or B cell- targeting antibody-mediated depletion strategies, which do not eliminate autoantibody-secreting plasma cells. -

Classification Decisions Taken by the Harmonized System Committee from the 47Th to 60Th Sessions (2011

CLASSIFICATION DECISIONS TAKEN BY THE HARMONIZED SYSTEM COMMITTEE FROM THE 47TH TO 60TH SESSIONS (2011 - 2018) WORLD CUSTOMS ORGANIZATION Rue du Marché 30 B-1210 Brussels Belgium November 2011 Copyright © 2011 World Customs Organization. All rights reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning translation, reproduction and adaptation rights should be addressed to [email protected]. D/2011/0448/25 The following list contains the classification decisions (other than those subject to a reservation) taken by the Harmonized System Committee ( 47th Session – March 2011) on specific products, together with their related Harmonized System code numbers and, in certain cases, the classification rationale. Advice Parties seeking to import or export merchandise covered by a decision are advised to verify the implementation of the decision by the importing or exporting country, as the case may be. HS codes Classification No Product description Classification considered rationale 1. Preparation, in the form of a powder, consisting of 92 % sugar, 6 % 2106.90 GRIs 1 and 6 black currant powder, anticaking agent, citric acid and black currant flavouring, put up for retail sale in 32-gram sachets, intended to be consumed as a beverage after mixing with hot water. 2. Vanutide cridificar (INN List 100). 3002.20 3. Certain INN products. Chapters 28, 29 (See “INN List 101” at the end of this publication.) and 30 4. Certain INN products. Chapters 13, 29 (See “INN List 102” at the end of this publication.) and 30 5. Certain INN products. Chapters 28, 29, (See “INN List 103” at the end of this publication.) 30, 35 and 39 6. Re-classification of INN products. -

Advances in Interferon-Alpha Targeting-Approaches for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Treatment

Full title: Advances in Interferon-alpha targeting-approaches for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus treatment Running title: Interferon-alpha targeting in SLE Authors: Filipa Farinha - Rheumatology Department, Centro Hospitalar do Baixo Vouga E.P.E. – Aveiro, Portugal David A Isenberg - Centre for Rheumatology, Division of Medicine, University College London – London, UK Correspondence to: Professor David Isenberg The Rayne Building Room 424, 4th Floor 5 University Street London WC1E 6JF E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 0044 203 108 2148 Fax: 0044 203 108 2152 1 Contents Summary 1. Introduction 1.1. IFN alpha 1.2. IFN alpha and SLE 2. IFN alpha targeting approaches 2.1. Anti-IFN alpha antibodies 2.2. Anti-IFN alpha receptor antibodies 2.3. IFN alpha Kinoid 3. Discussion 4. Conclusion Acknowledgements References 2 Summary Conventional therapies seem to have reached the limit of their ability to treat patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE). To improve the outcome for these patients, new drugs are needed. Several attempts have been made to introduce targeted therapies for this complex disease. One of these targets is Interferon (IFN) alpha, whose production is increased in SLE, contributing to its pathogenesis. In this review we consider some recent advances in IFN alpha targeting-approaches. Three monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against several IFN alpha subtypes have been tested in phase I and II trials, showing an acceptable safety profile and promising results in terms of reducing the IFN signature and disease activity. A mAb specific for the IFN alpha receptor and active immunization against IFN alpha are also being tested. Further trials will be essential to ascertain the safety and efficacy of all these approaches. -

New Drug Therapies for Systemic Lupus

icine- O ed pe M n l A a c n c r e e s t s n I Beenken, Intern Med 2018, 8:1 Internal Medicine: Open Access DOI: 10.4172/2165-8048.1000268 ISSN: 2165-8048 Review Article Open Access New Drug Therapies for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Review Beenken AE* Institute for Medical Immunology at the Campus Charité Mitte of the Medical Faculty of the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany *Corresponding author: Beenken AE, Institute for Medical Immunology, Berlin, Germany, Tel: 4915161419493; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: January 31, 2018; Accepted date: February 20, 2018; Published date: February 25, 2018 Copyright: © 2018 Beenken AE, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited Abstract From the literature research the belimumab studies were the only ones to meet the primary and some of the secondary endpoints. Introduction: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a multiorganic autoimmune disease caused by an immune reaction against DNA. Despite continuous research progress, the mortality of SLE patients is still 2‐4 times higher than the healthy populations and the standard drugs’ adverse effects (especially corticosteroids) hamper the patients’ quality of life. That is why there is an urgent need for new therapies. This paper reviews all phase III clinical trials of new SLE medication that were published since 2011 and analyses the drugs for their respective effects. Methods: MEDLINE (PubMed), Livivo, The Cochrane Library and Embase were systematically searched for relevant publications. -

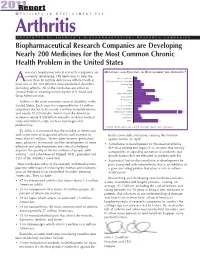

Report, Please Call the Telephone Number Listed

201R1e port M E D I C I N E S I N D E V E L O P M E N T F O R Arthritis P R E S E N T E D B Y A M E R I C A ’ S B I O P H A R M A C E U T I C A L R E S E A R C H C O M P A N I E S Biopharmaceutical Research Companies are Developing Nearly 200 Medicines for the Most Common Chronic Health Problem in the United States merica’s biopharmaceutical research companies are MEDICINES AND VACCINES IN DEVELOPMENT FOR ARTHRITIS* currently developing 198 medicines to help the Behcet’s Syndrome 3 more than 50 million Americans afflicted with at A Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy 6 least one of the 100 different musculoskeletal disorders, Fibromyalgia 9 including arthritis. All of the medicines are either in Gout 7 clinical trials or awaiting review by the U.S. Food and Lupus 19 Muscle Disorders 11 Drug Administration. Osteoarthritis 19 Osteoporosis 23 Arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the Pain 15 United States. Each year, it is responsible for 44 million Psoriatic Arthritis 7 outpatient doctor visits, nearly 1 million hospitalizations, Raynaud’s Disease 4 and nearly 10,000 deaths. And it costs the American Rheumatoid Arthritis 67 Scleroderma 6 economy nearly $128 billion annually in direct medical Spondylitis 7 costs and indirect costs, such as lost wages and Other 22 productivity. * Some medicines are listed in more than one category. -

MEDICAL JOURNAL Yongwen Jiang, Phd (USPS 464-820), a Monthly Publication, Is Deborah N

RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL Body Worlds Vital visits Rhode Island, page 66 R SPECIAL SECTION ADVANCES IN AUTOIMMUNE DISEASES GUEST EDITOR: EDWARD V. LALLY, MD DECember 2016 VOLUME 99 • NUMBER 12 ISSN 2327-2228 Your records are secure. Until they’re not. Data theft can happen to anyone, anytime. A misplaced mobile device can compromise your personal or patient records. RIMS IBC can get you the cyber liability insurance you need to protect yourself and your patients. Call us. 401-272-1050 IN COOPERATION WITH RIMS IBC RIMS INSURANCE BROKERAGE CORPORATION 405 PROMENADE STREET, SUITE B, PROVIDENCE RI 02908-4811 MEDICAL PROFESSIONAL/ CYBER LIABILITY PROPERTY/ CASUALTY LIFE/HEALTH/ DISABILITY RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL 18 Newer Treatment Strategies for Autoimmune Diseases EDWARD V. LALLY, MD GUEST EDITOR E. Lally, MD 19 Targeted Immunomodulatory Therapy: An Overview ASHLEY L. LEFEBVRE, PharmD, CDOE LAURA MCAULIFFE, PharmD: PGY2 23 Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A. Lefebvre, PharmD A Review of the Clinical Approach to Diagnosis and Update on Current Targeted Therapies JOANNE SZCZYGIEL CUNHA, MD KATARZYNA GILEK-SEIBERT, MD J. Cunha, MD 28 Pemphigus: Pathogenesis to Treatment K. Gilek-Siebert, MD CHRISTOPHER DIMARCO, MD 32 Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP): C. DiMarco, MD Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Current Treatment Strategies JACQUES REYNOLDS, DO GEORGE SACHS, MD, PhD G. Sachs, MD, PhD KARA STavROS, MD 36 Autoimmune Cytopenias: Diagnosis & Management CHRISTIAN P. NIXON, MD, PhD JOSEPH D. SWEENEY, MD C. Nixon, MD, PhD RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL 8 COMMENTARY Medical Tourism JOSEPH H. FRIEDMAN, MD Dickensian Diagnostics: The Diseases of Christmas Past What ailed Scrooge and Tiny Tim? HERBERT RAKATANSKY, MD Reconnecting with my Purpose in the Kingdom of Bhutan ERIC COHEN, MD 17 RIMJ AROUND THE WORLD New York, New York 58 RIMS NEWS Are you reading RIMS Notes? Working for You Weight + Wellness Summit Why You Should Join RIMS 66 SPOTLIGHT Body Worlds Exhibit: Anatomy Up Close & Personal MARY KORR 78 HeritaGE Dec. -

The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-)

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) in Autoimmune Disease and Current TNF-α Inhibitors in Therapeutics Dan-in Jang 1,†, A-Hyeon Lee 1,† , Hye-Yoon Shin 2, Hyo-Ryeong Song 1,3 , Jong-Hwi Park 1, Tae-Bong Kang 4 , Sang-Ryong Lee 5,* and Seung-Hoon Yang 1,* 1 Department of Medical Biotechnology, Collage of Life Science and Biotechnology, Dongguk University, Seoul 04620, Korea; [email protected] (D.-i.J.); [email protected] (A.-H.L.); [email protected] (H.-R.S.); [email protected] (J.-H.P.) 2 School of Life Science, Handong Global University, Pohang, Gyeongbuk 37554, Korea; [email protected] 3 Department of Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, Yonsei University, Seoul 03722, Korea 4 Department of Biotechnology, College of Biomedical and Health Science, Konkuk University, Chungju 27478, Korea; [email protected] 5 Department of Biological Environmental Science, Collage of Life Science and Biotechnology, Dongguk University, Seoul 04620, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.-R.L.); [email protected] (S.-H.Y.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) was initially recognized as a factor that causes the Citation: Jang, D.-i.; Lee, A-H.; Shin, necrosis of tumors, but it has been recently identified to have additional important functions as a H.-Y.; Song, H.-R.; Park, J.-H.; Kang, pathological component of autoimmune diseases. TNF-α binds to two different receptors, which T.-B.; Lee, S.-R.; Yang, S.-H. The Role initiate signal transduction pathways. -

Immunfarmakológia Immunfarmakológia

Gergely: Immunfarmakológia Immunfarmakológia Prof Gergely Péter Az immunpatológiai betegségek döntő többsége gyulladásos, és ennek következtében általában szövetpusztulással járó betegség, melyben – jelenleg – a terápia alapvetően a gyulladás csökkentésére és/vagy megszűntetésére irányul. Vannak kizárólag gyulladásgátló gyógyszereink és vannak olyanok, amelyek az immunreakció(k) bénításával (=immunszuppresszió révén) vagy emellett vezetnek a gyulladás mérsékléséhez. Mind szerkezetileg, mind hatástanilag igen sokféle csoportba oszthatók, az alábbi felosztás elsősorban didaktikus célokat szolgál. 1. Nem-szteroid gyulladásgátlók (‘nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs’ NSAID) 2. Kortikoszteroidok 3. Allergia-elleni szerek (antiallergikumok) 4. Sejtoszlás-gátlók (citosztatikumok) 5. Nem citosztatikus hatású immunszuppresszív szerek 6. Egyéb gyulladásgátlók és immunmoduláns szerek 7. Biológiai terápia 1. Nem-szteroid gyulladásgátlók (NSAID) Ezeket a vegyületeket, melyek őse a szalicilsav (jelenleg, mint acetilszalicilsav ‘aszpirin’ használatos), igen kiterjedten alkalmazzák a reumatológiában, az onkológiában és az orvostudomány szinte minden ágában, ahol fájdalom- és lázcsillapításra van szükség. Egyes felmérések szerint a betegek egy ötöde szed valamilyen NSAID készítményt. Szerkezetük alapján a készítményeket több csoportba sorolhatjuk: szalicilátok (pl. acetilszalicilsav) pyrazolidinek (pl. fenilbutazon) ecetsav származékok (pl. indometacin) fenoxiecetsav származékok (pl. diclofenac, aceclofenac)) oxicamok (pl. piroxicam, meloxicam) propionsav -

The Two Tontti Tudiul Lui Hi Ha Unit

THETWO TONTTI USTUDIUL 20170267753A1 LUI HI HA UNIT ( 19) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication (10 ) Pub. No. : US 2017 /0267753 A1 Ehrenpreis (43 ) Pub . Date : Sep . 21 , 2017 ( 54 ) COMBINATION THERAPY FOR (52 ) U .S . CI. CO - ADMINISTRATION OF MONOCLONAL CPC .. .. CO7K 16 / 241 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 39 / 3955 ANTIBODIES ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 31 /4706 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 31 / 165 ( 2013 .01 ) ; CO7K 2317 /21 (2013 . 01 ) ; (71 ) Applicant: Eli D Ehrenpreis , Skokie , IL (US ) CO7K 2317/ 24 ( 2013. 01 ) ; A61K 2039/ 505 ( 2013 .01 ) (72 ) Inventor : Eli D Ehrenpreis, Skokie , IL (US ) (57 ) ABSTRACT Disclosed are methods for enhancing the efficacy of mono (21 ) Appl. No. : 15 /605 ,212 clonal antibody therapy , which entails co - administering a therapeutic monoclonal antibody , or a functional fragment (22 ) Filed : May 25 , 2017 thereof, and an effective amount of colchicine or hydroxy chloroquine , or a combination thereof, to a patient in need Related U . S . Application Data thereof . Also disclosed are methods of prolonging or increasing the time a monoclonal antibody remains in the (63 ) Continuation - in - part of application No . 14 / 947 , 193 , circulation of a patient, which entails co - administering a filed on Nov. 20 , 2015 . therapeutic monoclonal antibody , or a functional fragment ( 60 ) Provisional application No . 62/ 082, 682 , filed on Nov . of the monoclonal antibody , and an effective amount of 21 , 2014 . colchicine or hydroxychloroquine , or a combination thereof, to a patient in need thereof, wherein the time themonoclonal antibody remains in the circulation ( e . g . , blood serum ) of the Publication Classification patient is increased relative to the same regimen of admin (51 ) Int . -

Antibodies to Watch in 2021 Hélène Kaplona and Janice M

MABS 2021, VOL. 13, NO. 1, e1860476 (34 pages) https://doi.org/10.1080/19420862.2020.1860476 PERSPECTIVE Antibodies to watch in 2021 Hélène Kaplona and Janice M. Reichert b aInstitut De Recherches Internationales Servier, Translational Medicine Department, Suresnes, France; bThe Antibody Society, Inc., Framingham, MA, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY In this 12th annual installment of the Antibodies to Watch article series, we discuss key events in antibody Received 1 December 2020 therapeutics development that occurred in 2020 and forecast events that might occur in 2021. The Accepted 1 December 2020 coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic posed an array of challenges and opportunities to the KEYWORDS healthcare system in 2020, and it will continue to do so in 2021. Remarkably, by late November 2020, two Antibody therapeutics; anti-SARS-CoV antibody products, bamlanivimab and the casirivimab and imdevimab cocktail, were cancer; COVID-19; Food and authorized for emergency use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the repurposed Drug Administration; antibodies levilimab and itolizumab had been registered for emergency use as treatments for COVID-19 European Medicines Agency; in Russia and India, respectively. Despite the pandemic, 10 antibody therapeutics had been granted the immune-mediated disorders; first approval in the US or EU in 2020, as of November, and 2 more (tanezumab and margetuximab) may Sars-CoV-2 be granted approvals in December 2020.* In addition, prolgolimab and olokizumab had been granted first approvals in Russia and cetuximab saratolacan sodium was first approved in Japan. The number of approvals in 2021 may set a record, as marketing applications for 16 investigational antibody therapeutics are already undergoing regulatory review by either the FDA or the European Medicines Agency.