Understanding Rook Endgames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZUGZWANGS in CHESS STUDIES G.Mcc. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. Van Der

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290629887 Zugzwangs in Chess Studies Article in ICGA journal · June 2011 DOI: 10.3233/ICG-2011-34205 CITATION READS 1 2,142 3 authors: Guy McCrossan Haworth Harold M.J.F. Van der Heijden University of Reading Gezondheidsdienst voor Dieren 119 PUBLICATIONS 354 CITATIONS 49 PUBLICATIONS 1,232 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Eiko Bleicher 7 PUBLICATIONS 12 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Chess Endgame Analysis View project The Skilloscopy project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Guy McCrossan Haworth on 23 January 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 82 ICGA Journal June 2011 NOTES ZUGZWANGS IN CHESS STUDIES G.McC. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. van der Heijden and E. Bleicher Reading, U.K., Deventer, the Netherlands and Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT Van der Heijden’s ENDGAME STUDY DATABASE IV, HHDBIV, is the definitive collection of 76,132 chess studies. The zugzwang position or zug, one in which the side to move would prefer not to, is a frequent theme in the literature of chess studies. In this third data-mining of HHDBIV, we report on the occurrence of sub-7-man zugs there as discovered by the use of CQL and Nalimov endgame tables (EGTs). We also mine those Zugzwang Studies in which a zug more significantly appears in both its White-to-move (wtm) and Black-to-move (btm) forms. We provide some illustrative and extreme examples of zugzwangs in studies. -

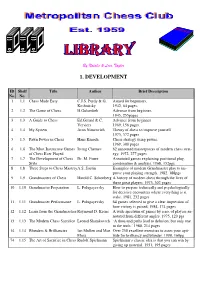

1. Development

By Natalie & Leon Taylor 1. DEVELOPMENT ID Shelf Title Author Brief Description No. No. 1 1.1 Chess Made Easy C.J.S. Purdy & G. Aimed for beginners, Koshnitsky 1942, 64 pages. 2 1.2 The Game of Chess H.Golombek Advance from beginner, 1945, 255pages 3 1.3 A Guide to Chess Ed.Gerard & C. Advance from beginner Verviers 1969, 156 pages. 4 1.4 My System Aron Nimzovich Theory of chess to improve yourself 1973, 372 pages 5 1.5 Pawn Power in Chess Hans Kmoch Chess strategy using pawns. 1969, 300 pages 6 1.6 The Most Instructive Games Irving Chernev 62 annotated masterpieces of modern chess strat- of Chess Ever Played egy. 1972, 277 pages 7 1.7 The Development of Chess Dr. M. Euwe Annotated games explaining positional play, Style combination & analysis. 1968, 152pgs 8 1.8 Three Steps to Chess MasteryA.S. Suetin Examples of modern Grandmaster play to im- prove your playing strength. 1982, 188pgs 9 1.9 Grandmasters of Chess Harold C. Schonberg A history of modern chess through the lives of these great players. 1973, 302 pages 10 1.10 Grandmaster Preparation L. Polugayevsky How to prepare technically and psychologically for decisive encounters where everything is at stake. 1981, 232 pages 11 1.11 Grandmaster Performance L. Polugayevsky 64 games selected to give a clear impression of how victory is gained. 1984, 174 pages 12 1.12 Learn from the Grandmasters Raymond D. Keene A wide spectrum of games by a no. of players an- notated from different angles. 1975, 120 pgs 13 1.13 The Modern Chess Sacrifice Leonid Shamkovich ‘A thousand paths lead to delusion, but only one to the truth.’ 1980, 214 pages 14 1.14 Blunders & Brilliancies Ian Mullen and Moe Over 250 excellent exercises to asses your apti- Moss tude for brilliancy and blunder. -

Chess Endgame News

Chess Endgame News Article Published Version Haworth, G. (2014) Chess Endgame News. ICGA Journal, 37 (3). pp. 166-168. ISSN 1389-6911 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/38987/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 166 ICGA Journal September 2014 CHESS ENDGAME NEWS G.McC. Haworth1 Reading, UK This note investigates the recently revived proposal that the stalemated side should lose, and comments further on the information provided by the FRITZ14 interface to Ronald de Man’s DTZ50 endgame tables (EGTs). Tables 1 and 2 list relevant positions: data files (Haworth, 2014b) provide chess-line sources and annotation. Pos.w-b Endgame FEN Notes g1 3-2 KBPKP 8/5KBk/8/8/p7/P7/8/8 b - - 34 124 Korchnoi - Karpov, WCC.5 (1978) g2 3-3 KPPKPP 8/6p1/5p2/5P1K/4k2P/8/8/8 b - - 2 65 Anand - Kramnik, WCC.5 (2007) 65. … Kxf5 g3 3-2 KRKRB 5r2/8/8/8/8/3kb3/3R4/3K4 b - - 94 109 Carlsen - van Wely, Corus (2007) 109. … Bxd2 == g4 7-7 KQR..KQR.. 2Q5/5Rpk/8/1p2p2p/1P2Pn1P/5Pq1/4r3/7K w Evans - Reshevsky, USC (1963), 49. -

1979 September 29

I position with International flocked to see; To sorri{ of position and succumbed to · Chess - Masters Jonathan Speelman the top established players John Littlewood. In round> and Robert · Bellin until in · they represented vultures I 0, as Black in a Frerich (' . round eight the sensational come to witness the greatest. again, Short drew with Nunn. Short caught happened. As White against "humiliation" of British chess In the last round he met. Short, Miles selected an indif• ~r~a~! • 27-yeai:-old Robert Bellin, THIS YEAR's British Chain- an assistant at his Interzonal ferent line against the French Next up was defending also on 7½ points. Bellin · pionship was one of the most tournament. More quietly, at defence and was thrashed off champion '. Speelman, stood to win the champion- · sensational ever. The stage the other end of the scale, 14- the board. amusingly described along _ ship on tie-break if they drew was set when Grandmaster year-old Nigel Short scraped _ Turmoil reigned! Short had with Miles as· "having the the game as he had faced J - Tony Miles flew in from an in because the selected field great talent and an already physique of a boxer" in pub• stronger opposition earlier in international in Argentina . was then· extended to 48 formidable reputation - but lic information leaflets. Short the event. Against Bellin, and decided to exercise his players. no one had -foreseen this. He defeated Speelman as well to Short rattled off his moves special last-minute entry op- Miles began impressively, .couldn't possibly · win the take the sole lead on seven like · a machinegun in the tion, apparently because he. -

Award of the John Nunn 50Th Birthday Study Tourney

Award of the John Nunn 50th Birthday Study Tourney I am pleased to announce the results of the John Nunn 50th Birthday Study Tourney. First, a few words about the administration of the event. The closing date for entries was the end of October 2005. Round about this time, the tourney controller Brian Stephenson converted the entries to PGN format and passed the entries to me without the composers’ names. During the following month, I checked the studies for analytical soundness. At the start of De- cember, those unsound studies which seemed capable of repair were returned to the composers for correction, with a further month being allowed for this step. Although a few studies which would have featured in the award could not be corrected, several other studies were successfully repaired. Many of the corrected studies ended up in the award, so this was a worthwhile step. At this stage, there were 59 studies still in the tourney. I then made a preliminary selection of studies for the award and these were sent to Harold van der Heijden for anticipation checking. Only a couple of studies turned out to be seriously anticipated, although some partial anticipations led to changes in the order of the award. I then re-checked the studies in the award for soundness, which unfortu- nately resulted in one prize-winner being removed from the award. The standard of the entries was very high. Although I was quite tough with the judging, there are 30 studies in the award. I accept that some of the studies not in the award would certainly have been honoured in many other tourneys; likewise some of the lower-ranked studies in this award would have gained prizes elsewhere. -

John Nunn's Problem Section in Inter• Robert Bellin Won on Tie-Break and Cutty Sark £2000 Grand Prix All to National Chess; a New Magazine Which

NZ LIST 13, 8Xh5 gXh5 • Nunn's counter-attack has succeeded 14. Bb2 Bd7 15. Rae1 QM in exchanging a pair _of rooks. 27. Qh5. ch would have lost neatly to tz ... Kj8 ,II For his broken pawns Black has the 28.Bg7 ch Kg8. kingside. initiative on the White's next 27 ·::. ; . 0Xe1 ch John N'unn_ ~ forgott~n . man move is over-ambitious - consolidation is. Kg2 Res . ENGLISH GRANDMASTER John because· of England's fine overall with l6.f3 or 16.Ndl is called for. 29. f6 Kd7 Nunn, age 25, might justifiably soon performance. If eyer there wasn't 16. f4?I Ng4 30. QXh7 Qd2ch 17. Nf3 31. Kg3 0Xd5 start to' feel· jinxed, as .the finer mo- a day to slaughter . Russian Lev 32. Kh4 Re8 ments of his chess career have-tended Polugayevsky, it was the day Nunn's 33. Resigns. to coincide with other great events. countryman Tony, Miles beat World He was the "unknown" third man in Champion Anatoly Karpov! The following puzzle comes· from the last British' championships ~ .However. Nunn did win the 1979 John Nunn's problem section in Inter• Robert Bellin won on tie-break and Cutty Sark £2000 grand prix all to national Chess; a new magazine which . 14-year-old Nigel Short got' all the himself, for being the most successful I mentioned in this column several publicity. : player on the. UK circuit, I got the months ago. Unfortunately, despite a · ;; At Hastirrgs over Christmas his first · considerably smaller second prize and great. · need for . this type of pub• · equal ahead.of a strong foreign con- a quantity of whisky, presumably to lication, it does not seem to have sur-1 •• tingent again took a· back seat - this console myself. -

The Queen's Gambit

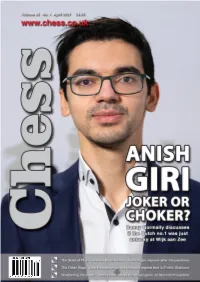

01-01 Cover - April 2021_Layout 1 16/03/2021 13:03 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/03/2021 11:45 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Associate Editor: John Saunders 60 Seconds with...Geert van der Velde.....................................................7 Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington We catch up with the Play Magnus Group’s VP of Content Chess Magazine (ISSN 0964-6221) is published by: A Tale of Two Players.........................................................................................8 Chess & Bridge Ltd, 44 Baker St, London, W1U 7RT Wesley So shone while Carlsen struggled at the Opera Euro Rapid Tel: 020 7486 7015 Anish Giri: Choker or Joker?........................................................................14 Email: [email protected], Website: www.chess.co.uk Danny Gormally discusses if the Dutch no.1 was just unlucky at Wijk Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Daniel King also takes a look at the play of Anish Giri Twitter: @chessandbridge The Other Saga ..................................................................................................22 Subscription Rates: John Henderson very much -

Petts Wood and Orpington Chess Club

PETTS WOOD AND ORPINGTON CHESS CLUB www.pwchessclub.org.uk The club meets at St John’s URC, Lynwood Grove, Orpington, BR6 0BG Fridays 19:30 to 22:15 mid-September to the end of April Visitors are most welcome. Please contact the club secretary with any enquiries. Chairman: Paul Jones 98 Eden Way, Beckenham, BR3 3DH H: 020 8663 6212 Secretary: Ralph Ambrose 12 Ringshall Road, Orpington BR5 2LZ M: 07976 726 765 Treasurer: Rajesh Suseelan 89 Clareville Road, Orpington, BR5 1RU M: 07771 976 327 E-mails: [email protected] | [email protected] | [email protected] RECOMMENDED READING These can be obtained from www.amazon.co.uk, often at a discount and with free delivery. Alternatively, your local library is obliged to obtain any title you’d like to borrow (if it is in print). The Right Way to Play Chess by D Brine Pritchard; Elliott Right Way Books; 223pp pb £7.99 General guidance and principles for the complete beginner or novice player. The Mammoth Book of Chess by Graham Burgess and John Nunn; Robinson; 538pp pb £9.99 A superb introduction to chess for the more serious player. Tactics; delivering mate; the openings; attack and defence; and just about every other subject is at least touched on. BCF Book of the Year, 1997. The World’s Greatest Chess Games by Graham Burgess, et alia; Robinson; 560pp pb £9.99 The companion volume. 100 pyrotechnic games by all the world champions and other great players, each annotated by a Grandmaster (John Nunn or John Emms) or International Master (Graham Burgess). -

Background I Spent 30 Years Working in the Ministry of Defence in the UK

The Watch Oak, Chain Lane, Battle, East Sussex TN33 0YD Telephone 01424 775222 Email [email protected] Website www.englishchess.org.uk A Company Limited by Guarantee | Registered in England and Wales Registration No. 5293039 | VAT Registration No 195643626 Affiliated to Fédération Internationale des Échecs Carl S Portman MCIPS MILT MinstLM BIO Background I spent 30 years working in the Ministry of Defence in the UK and Germany. In that time, I worked in several key roles but relevant to the ECF Development Officer role is Change Management, Audit, Operations Management, Head of Communications, Secretariat (where I occasionally advised and presented at Ministerial and Senior Military levels), and Project Management. I managed a Distribution Outlet for the Military in Germany for several years in a stand-alone position. I have supported logistical back up in the Falklands, Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts among others and my many civilian and military courses and workshops have given me the skill set to manage, motivate and deliver and to get results both in the workplace and life. My membership of the Institute of Leadership and Management has also proved very worthwhile in managing and engaging with people. I took voluntary early release in 2011 to take up writing, lecturing, travel, chess coaching and management consultancy. I still visit my old Officer’s Mess when I want to get away from it all! Education I went to work (on a farm!) only a couple of days after I left secondary school so there was no college or university for me. However, in my adult life I obtained a degree, managed to write three books (including Chess Behind Bars) and engage in many lectures and talks – and I learned most from real people in the University of life. -

Move by Move

Zenón Franco Lasker move by move www.everymanchess.com About the Author is a Grandmaster from Paraguay, now living in Spain. He represented Zenón Franco Paraguay, on top board, in seven Chess Olympiads, and won individual gold medals at Lucerne 1982 and Novi Sad 1990. He’s an experienced trainer and has written numerous books on chess. Also by the Author: Test Your Chess Anand: Move by Move Spassky: Move by Move Rubinstein: Move by Move Keres: Move by Move Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Preface 7 Introduction 9 Selected Games 1 1889-1894 36 2 1895-1900 128 3 1901-1910 236 4 1914-1925 335 5 Final Years: 1934-1936 416 Index of Openings 446 Index of Complete Games 447 Preface The Danish Grandmaster Bent Larsen spent many years living in Spain and Argentina and he noted that Spanish speakers, as your author is, hold José Raúl Capablanca in par- ticularly high esteem, due to the linguistic connection, and as a consequence we have tended to seriously undervalue two of his great rivals, the Russian Alexander Alekhine and the subject of this book, Emanuel Lasker of Germany. It is possible that Larsen was right; it’s certainly true that until recently there were not many good books about Lasker. Recently, however, an excellent book, John Nunn’s Chess Course, was published, in which Nunn deeply analyzes Lasker’s play. As soon I was assigned the gratifying task of writing the present book I naturally stud- ied Lasker’s games more deeply than I had done in the past, and for more than a year there has scarcely been a day when I haven’t marvelled at his strength. -

Understanding Minor Piece Endgames

Understanding Minor Piece Endgames Karsten Müller and Yakov Konoval Foreword by Jacob Aagaard 2018 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 1 Understanding Minor Piece Endgames by Karsten Müller and Yakov Konoval ISBN: 978-1-941270-78-3 (print) ISBN: 978-1-941270-79-0 (eBook) © Copyright 2018 Karsten Müller and Yakov Konoval All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover by Janel Lowrance Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Bibliography 4 Preface 5 Foreword 6 The History of Creating Seven-Piece Endgame Tablebases 7 Chapter 1 Knight vs. Pawn Endgames 14 Chapter 2 Knight Endgames 63 Chapter 3 Bishop and Pawns vs. Pawns Endgames 95 Chapter 4 Same-Color Bishops Endgames 140 Chapter 5 Opposite-Color Bishop Endgames 174 Chapter 6 Bishop vs. Knight Endgames 196 Chapter 7 Computer Endgames 314 Chapter 8 Endgame Studies 324 Solutions 327 3 Understanding Minor Piece Endgames Bibliography Fundamental Chess Endings, Karsten Müller and Frank Lamprecht, Gambit 2001 How to Play Chess Endgames, Karsten Müller and Wolfgang Pajeken, Gambit 2008 Understanding Rook Endgames, Karsten Müller and Yakov Konoval, Gambit 2016 Understanding Chess Endgames, John Nunn, Gambit 2009 Nunn’s Chess Endings, John Nunn, Gambit 2010 Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual, Mark Dvoretsky, Russell Enterprises 2003, 4th edition 2014 Encyclopedia of Chess Endings (ECE v. -

My 10 Chess Heroes

The ICC and Coach Dan Heisman present: My 10 Chess Heroes The Internet Chess Club and Coach Dan Heisman present My 10 Chess Heroes The ICC and Coach Dan Heisman present: My 10 Chess Heroes This is a guide that comes with the video course “My 10 Chess Heroes”. We highly recommend you watch the video series AND read this Course Guide to enjoy your product! To watch the videos, click here The ICC and Coach Dan Heisman present: My 10 Chess Heroes Since the beginning of the modern chess era, players like Morphy, Lasker, Keres, Spassky, Fischer, Kasparov, Carlsen and many others have ruled the world of the 64-square board, inspiring and influencing people devoted to the noble game. Studying their games and their life is the fuel that feeds the engines of millions of players. It's almost impossible to become a good chess player without the knowledge that these great artists of the board have given us. In this fantastic video-series, renowned coach Dan Heisman, with his unmistakable and easy- to-understand style, shares with you stories and games of his ten chess heroes. Dan takes you on a journey that will help to discover tactics, positional play, error management, initiative, defense, and all of this presented you by some of the greatest players ever! Here is a list with Dan's 10 chess heroes: Paul Morphy Emanuel Lasker Paul Keres Donald Byrne David Bronstein Boris Spassky Robert J. Fischer John Nunn Garry Kasparov Alexei Shirov In the videos, Dan analyzes and discuss games, showing the style of play, tricks, and nuances that characterize the uniqueness of each of these "monsters.".