Move by Move

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZUGZWANGS in CHESS STUDIES G.Mcc. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. Van Der

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290629887 Zugzwangs in Chess Studies Article in ICGA journal · June 2011 DOI: 10.3233/ICG-2011-34205 CITATION READS 1 2,142 3 authors: Guy McCrossan Haworth Harold M.J.F. Van der Heijden University of Reading Gezondheidsdienst voor Dieren 119 PUBLICATIONS 354 CITATIONS 49 PUBLICATIONS 1,232 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Eiko Bleicher 7 PUBLICATIONS 12 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Chess Endgame Analysis View project The Skilloscopy project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Guy McCrossan Haworth on 23 January 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 82 ICGA Journal June 2011 NOTES ZUGZWANGS IN CHESS STUDIES G.McC. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. van der Heijden and E. Bleicher Reading, U.K., Deventer, the Netherlands and Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT Van der Heijden’s ENDGAME STUDY DATABASE IV, HHDBIV, is the definitive collection of 76,132 chess studies. The zugzwang position or zug, one in which the side to move would prefer not to, is a frequent theme in the literature of chess studies. In this third data-mining of HHDBIV, we report on the occurrence of sub-7-man zugs there as discovered by the use of CQL and Nalimov endgame tables (EGTs). We also mine those Zugzwang Studies in which a zug more significantly appears in both its White-to-move (wtm) and Black-to-move (btm) forms. We provide some illustrative and extreme examples of zugzwangs in studies. -

1. Development

By Natalie & Leon Taylor 1. DEVELOPMENT ID Shelf Title Author Brief Description No. No. 1 1.1 Chess Made Easy C.J.S. Purdy & G. Aimed for beginners, Koshnitsky 1942, 64 pages. 2 1.2 The Game of Chess H.Golombek Advance from beginner, 1945, 255pages 3 1.3 A Guide to Chess Ed.Gerard & C. Advance from beginner Verviers 1969, 156 pages. 4 1.4 My System Aron Nimzovich Theory of chess to improve yourself 1973, 372 pages 5 1.5 Pawn Power in Chess Hans Kmoch Chess strategy using pawns. 1969, 300 pages 6 1.6 The Most Instructive Games Irving Chernev 62 annotated masterpieces of modern chess strat- of Chess Ever Played egy. 1972, 277 pages 7 1.7 The Development of Chess Dr. M. Euwe Annotated games explaining positional play, Style combination & analysis. 1968, 152pgs 8 1.8 Three Steps to Chess MasteryA.S. Suetin Examples of modern Grandmaster play to im- prove your playing strength. 1982, 188pgs 9 1.9 Grandmasters of Chess Harold C. Schonberg A history of modern chess through the lives of these great players. 1973, 302 pages 10 1.10 Grandmaster Preparation L. Polugayevsky How to prepare technically and psychologically for decisive encounters where everything is at stake. 1981, 232 pages 11 1.11 Grandmaster Performance L. Polugayevsky 64 games selected to give a clear impression of how victory is gained. 1984, 174 pages 12 1.12 Learn from the Grandmasters Raymond D. Keene A wide spectrum of games by a no. of players an- notated from different angles. 1975, 120 pgs 13 1.13 The Modern Chess Sacrifice Leonid Shamkovich ‘A thousand paths lead to delusion, but only one to the truth.’ 1980, 214 pages 14 1.14 Blunders & Brilliancies Ian Mullen and Moe Over 250 excellent exercises to asses your apti- Moss tude for brilliancy and blunder. -

Ed Van De Gevel Trying to Figure out the Rules of a Futuristic Chess Set

No. 143 -(VoJ.IX) ISSN-0012-7671 Copyright ARVES Reprinting of (parts of) this magazine is only permitted for non commercial purposes and with acknowledgement. January 2002 Ed van de Gevel trying to figure out the rules of a futuristic chess set. 493 Editorial Board EG Subscription John Roycroft, 17 New Way Road, London, England NW9 6PL e-mail: [email protected] EG is produced by the Dutch-Flemish Association for Endgame Study Ed van de Gevel, ('Alexander Rueb Vereniging voor Binnen de Veste 36, schaakEindspelStudie') ARVES. Subscrip- 3811 PH Amersfoort, tion to EG is not tied to membership of The Netherlands ARVES. e-mail: [email protected] The annual subscription of EG (Jan. 1 - Dec.31) is EUR 22 for 4 issues. Payments Harold van der Heijden, should be in EUR and can be made by Michel de Klerkstraat 28, bank notes, Eurocheque (please fill in your 7425 DG Deventer, validation or garantee number on the The Netherlands back), postal money order, Eurogiro or . -e-mail: harold van der [email protected] bank cheque. To compensate for bank charges payments via Eurogiro or bank Spotlight-column: cheque should be EUR 27 and EUR 31 Jurgen Fleck, respectively, instead of 22. NeuerWeg 110, Some of the above mentioned methods of D-47803 Krefeld, payment may not longer be valid in 2002! Germany Please inform about this at your bank!! e-mail: juergenlleck^t-online.de All payments can be addressed to the Originals-column: treasurer (see Editorial Board) except those Noam D. Elkies by Eurogiro which should be directed to: Dept of Mathematics, Postbank, accountnumber 54095, in the SCIENCE CENTER name of ARVES, Leiderdorp, The Nether- One Oxford Street, lands. -

Chess Endgame News

Chess Endgame News Article Published Version Haworth, G. (2014) Chess Endgame News. ICGA Journal, 37 (3). pp. 166-168. ISSN 1389-6911 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/38987/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 166 ICGA Journal September 2014 CHESS ENDGAME NEWS G.McC. Haworth1 Reading, UK This note investigates the recently revived proposal that the stalemated side should lose, and comments further on the information provided by the FRITZ14 interface to Ronald de Man’s DTZ50 endgame tables (EGTs). Tables 1 and 2 list relevant positions: data files (Haworth, 2014b) provide chess-line sources and annotation. Pos.w-b Endgame FEN Notes g1 3-2 KBPKP 8/5KBk/8/8/p7/P7/8/8 b - - 34 124 Korchnoi - Karpov, WCC.5 (1978) g2 3-3 KPPKPP 8/6p1/5p2/5P1K/4k2P/8/8/8 b - - 2 65 Anand - Kramnik, WCC.5 (2007) 65. … Kxf5 g3 3-2 KRKRB 5r2/8/8/8/8/3kb3/3R4/3K4 b - - 94 109 Carlsen - van Wely, Corus (2007) 109. … Bxd2 == g4 7-7 KQR..KQR.. 2Q5/5Rpk/8/1p2p2p/1P2Pn1P/5Pq1/4r3/7K w Evans - Reshevsky, USC (1963), 49. -

1979 September 29

I position with International flocked to see; To sorri{ of position and succumbed to · Chess - Masters Jonathan Speelman the top established players John Littlewood. In round> and Robert · Bellin until in · they represented vultures I 0, as Black in a Frerich (' . round eight the sensational come to witness the greatest. again, Short drew with Nunn. Short caught happened. As White against "humiliation" of British chess In the last round he met. Short, Miles selected an indif• ~r~a~! • 27-yeai:-old Robert Bellin, THIS YEAR's British Chain- an assistant at his Interzonal ferent line against the French Next up was defending also on 7½ points. Bellin · pionship was one of the most tournament. More quietly, at defence and was thrashed off champion '. Speelman, stood to win the champion- · sensational ever. The stage the other end of the scale, 14- the board. amusingly described along _ ship on tie-break if they drew was set when Grandmaster year-old Nigel Short scraped _ Turmoil reigned! Short had with Miles as· "having the the game as he had faced J - Tony Miles flew in from an in because the selected field great talent and an already physique of a boxer" in pub• stronger opposition earlier in international in Argentina . was then· extended to 48 formidable reputation - but lic information leaflets. Short the event. Against Bellin, and decided to exercise his players. no one had -foreseen this. He defeated Speelman as well to Short rattled off his moves special last-minute entry op- Miles began impressively, .couldn't possibly · win the take the sole lead on seven like · a machinegun in the tion, apparently because he. -

Award of the John Nunn 50Th Birthday Study Tourney

Award of the John Nunn 50th Birthday Study Tourney I am pleased to announce the results of the John Nunn 50th Birthday Study Tourney. First, a few words about the administration of the event. The closing date for entries was the end of October 2005. Round about this time, the tourney controller Brian Stephenson converted the entries to PGN format and passed the entries to me without the composers’ names. During the following month, I checked the studies for analytical soundness. At the start of De- cember, those unsound studies which seemed capable of repair were returned to the composers for correction, with a further month being allowed for this step. Although a few studies which would have featured in the award could not be corrected, several other studies were successfully repaired. Many of the corrected studies ended up in the award, so this was a worthwhile step. At this stage, there were 59 studies still in the tourney. I then made a preliminary selection of studies for the award and these were sent to Harold van der Heijden for anticipation checking. Only a couple of studies turned out to be seriously anticipated, although some partial anticipations led to changes in the order of the award. I then re-checked the studies in the award for soundness, which unfortu- nately resulted in one prize-winner being removed from the award. The standard of the entries was very high. Although I was quite tough with the judging, there are 30 studies in the award. I accept that some of the studies not in the award would certainly have been honoured in many other tourneys; likewise some of the lower-ranked studies in this award would have gained prizes elsewhere. -

John Nunn's Problem Section in Inter• Robert Bellin Won on Tie-Break and Cutty Sark £2000 Grand Prix All to National Chess; a New Magazine Which

NZ LIST 13, 8Xh5 gXh5 • Nunn's counter-attack has succeeded 14. Bb2 Bd7 15. Rae1 QM in exchanging a pair _of rooks. 27. Qh5. ch would have lost neatly to tz ... Kj8 ,II For his broken pawns Black has the 28.Bg7 ch Kg8. kingside. initiative on the White's next 27 ·::. ; . 0Xe1 ch John N'unn_ ~ forgott~n . man move is over-ambitious - consolidation is. Kg2 Res . ENGLISH GRANDMASTER John because· of England's fine overall with l6.f3 or 16.Ndl is called for. 29. f6 Kd7 Nunn, age 25, might justifiably soon performance. If eyer there wasn't 16. f4?I Ng4 30. QXh7 Qd2ch 17. Nf3 31. Kg3 0Xd5 start to' feel· jinxed, as .the finer mo- a day to slaughter . Russian Lev 32. Kh4 Re8 ments of his chess career have-tended Polugayevsky, it was the day Nunn's 33. Resigns. to coincide with other great events. countryman Tony, Miles beat World He was the "unknown" third man in Champion Anatoly Karpov! The following puzzle comes· from the last British' championships ~ .However. Nunn did win the 1979 John Nunn's problem section in Inter• Robert Bellin won on tie-break and Cutty Sark £2000 grand prix all to national Chess; a new magazine which . 14-year-old Nigel Short got' all the himself, for being the most successful I mentioned in this column several publicity. : player on the. UK circuit, I got the months ago. Unfortunately, despite a · ;; At Hastirrgs over Christmas his first · considerably smaller second prize and great. · need for . this type of pub• · equal ahead.of a strong foreign con- a quantity of whisky, presumably to lication, it does not seem to have sur-1 •• tingent again took a· back seat - this console myself. -

The Queen's Gambit

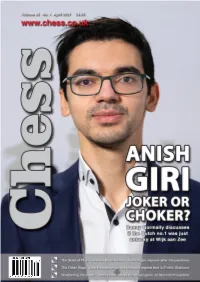

01-01 Cover - April 2021_Layout 1 16/03/2021 13:03 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/03/2021 11:45 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Associate Editor: John Saunders 60 Seconds with...Geert van der Velde.....................................................7 Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington We catch up with the Play Magnus Group’s VP of Content Chess Magazine (ISSN 0964-6221) is published by: A Tale of Two Players.........................................................................................8 Chess & Bridge Ltd, 44 Baker St, London, W1U 7RT Wesley So shone while Carlsen struggled at the Opera Euro Rapid Tel: 020 7486 7015 Anish Giri: Choker or Joker?........................................................................14 Email: [email protected], Website: www.chess.co.uk Danny Gormally discusses if the Dutch no.1 was just unlucky at Wijk Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Daniel King also takes a look at the play of Anish Giri Twitter: @chessandbridge The Other Saga ..................................................................................................22 Subscription Rates: John Henderson very much -

The English School of Chess: a Nation on Display, 1834-1904

Durham E-Theses The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904 HARRISON, EDWARD,GRAHAM How to cite: HARRISON, EDWARD,GRAHAM (2018) The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/12703/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904 Edward Harrison This thesis is submitted for the degree of MA by Research in the department of History at Durham University March 2018 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the author's prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. -

Amos Burn: a Chess Biography / Mcfarland & Company, 2004 / 972 Pages / 9780786417179 / Richard Forster / 2004

Amos Burn: A Chess Biography / McFarland & Company, 2004 / 972 pages / 9780786417179 / Richard Forster / 2004 "Must be considered the definitive biography of the Englishman Amos Burn. It's an incredible achievement. Four Stars." - -Chess Horizons. "Richard Forster and McFarland have done the chess world proud with this volume...Forster has happily found a publisher willing and able to give the subject the treatment it deserves." - -Chess Mail. Read more. About the Author. Richard Forster holds a doctorate in computational linguistics and the international master title in chess. He works as a technical writer in information technology and is also the chess columnist of the Neue AMOS BURN. A Chess Biography. Richard Forster. Foreword by Victor Korchnoi. McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson NC, 2004. 984 pages (8.5 x 11 inches) and 2.5 kg of pure chess history, with almost 800 annotated games, 209 photographs and illustrations and 6 indexes. Deep coverage of all aspects of 19th century chess life, at both international and club levels, with a detailed presentation of chess life in Liverpool and London. Comprehensive source indications and bibliography. Illustrations of Burn and most of his opponents. and much more. Comments and Corrections. Viewable chess game Joseph Henry Blackburne vs Amos Burn, 1868, with discussion forum and chess analysis features. Coles indicates that Burn took up chess in about 1866, and he was introduced to the Liverpool chess club in 1867. He was put into the club's Class II - the Pawn & Move class, and in his first season he won the club's handicap tournament. With practice at the club against experts such as the Rev. -

John D. Rockefeller V Embraces Family Legacy with $3 Million Giff to US Chess

Included with this issue: 2021 Annual Buying Guide John D. Rockefeller V Embraces Family Legacy with $3 Million Giftto US Chess DECEMBER 2020 | USCHESS.ORG The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com So you want to improve your chess? NEW! If you want to improve your chess the best place to start is looking how the great champs did it. dŚƌĞĞͲƟŵĞh͘^͘ŚĂŵƉŝŽŶĂŶĚǁĞůůͲ known chess educator Joel Benjamin ŝŶƚƌŽĚƵĐĞƐĂůůtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶƐĂŶĚ shows what is important about their play and what you can learn from them. ĞŶũĂŵŝŶƉƌĞƐĞŶƚƐƚŚĞŵŽƐƚŝŶƐƚƌƵĐƟǀĞ games of each champion. Magic names ƐƵĐŚĂƐĂƉĂďůĂŶĐĂ͕ůĞŬŚŝŶĞ͕dĂů͕<ĂƌƉŽǀ ĂŶĚ<ĂƐƉĂƌŽǀ͕ƚŚĞLJ͛ƌĞĂůůƚŚĞƌĞ͕ƵƉƚŽ ĐƵƌƌĞŶƚtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶDĂŐŶƵƐĂƌůƐĞŶ͘ Of course the crystal-clear style of Bobby &ŝƐĐŚĞƌ͕ƚŚĞϭϭƚŚtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶ͕ŵĂŬĞƐ for a very memorable chapter. ^ƚƵĚLJŝŶŐƚŚŝƐŬǁŝůůƉƌŽǀĞĂŶĞdžƚƌĞŵĞůLJ ƌĞǁĂƌĚŝŶŐĞdžƉĞƌŝĞŶĐĞĨŽƌĂŵďŝƟŽƵƐ LJŽƵŶŐƐƚĞƌƐ͘ůŽƚŽĨƚƌĂŝŶĞƌƐĂŶĚĐŽĂĐŚĞƐ ǁŝůůĮŶĚŝƚǁŽƌƚŚǁŚŝůĞƚŽŝŶĐůƵĚĞƚŚĞŬ in their curriculum. paperback | 256 pages | $22.95 from the publishers of A Magazine Free Ground Shipping On All Books, Software and DVDS at US Chess Sales $25.00 Minimum – Excludes Clearance, Shopworn and Items Otherwise Marked CONTRIBUTORS DECEMBER Dan Lucas (Cover Story) Dan Lucas is the Senior Director of Strategic Communication for US Chess. He served as the Editor for Chess Life from 2006 through 2018, making him one of the longest serving editors in US Chess history. This is his first cover story forChess Life. { EDITORIAL } CHESS LIFE/CLO EDITOR John Hartmann ([email protected]) -

Petts Wood and Orpington Chess Club

PETTS WOOD AND ORPINGTON CHESS CLUB www.pwchessclub.org.uk The club meets at St John’s URC, Lynwood Grove, Orpington, BR6 0BG Fridays 19:30 to 22:15 mid-September to the end of April Visitors are most welcome. Please contact the club secretary with any enquiries. Chairman: Paul Jones 98 Eden Way, Beckenham, BR3 3DH H: 020 8663 6212 Secretary: Ralph Ambrose 12 Ringshall Road, Orpington BR5 2LZ M: 07976 726 765 Treasurer: Rajesh Suseelan 89 Clareville Road, Orpington, BR5 1RU M: 07771 976 327 E-mails: [email protected] | [email protected] | [email protected] RECOMMENDED READING These can be obtained from www.amazon.co.uk, often at a discount and with free delivery. Alternatively, your local library is obliged to obtain any title you’d like to borrow (if it is in print). The Right Way to Play Chess by D Brine Pritchard; Elliott Right Way Books; 223pp pb £7.99 General guidance and principles for the complete beginner or novice player. The Mammoth Book of Chess by Graham Burgess and John Nunn; Robinson; 538pp pb £9.99 A superb introduction to chess for the more serious player. Tactics; delivering mate; the openings; attack and defence; and just about every other subject is at least touched on. BCF Book of the Year, 1997. The World’s Greatest Chess Games by Graham Burgess, et alia; Robinson; 560pp pb £9.99 The companion volume. 100 pyrotechnic games by all the world champions and other great players, each annotated by a Grandmaster (John Nunn or John Emms) or International Master (Graham Burgess).