Publius and the Science of the Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May, 2019 George Washington Chapter in April "65Th Anniversary"

George Washington Chapter Sons of the American Revolution Newsletter Visit us online at www.gwsar.org Volume 20, Issue 5 May, 2019 George Washington Chapter in April "65th Anniversary" The George Washington Chapter celebrated its 65th year on April 13, 2019 at the Mount Vernon Country Club in Alexandria, with over 70 compatriots and guests in attendance. The chapter was chartered on April 2, 1954 with 14 charter members. Today, the chapter has over 250 members and continues to grow. (April Con't on Page 4) George Washington Chapter Sons of the American Revolution ~ Alexandria, Virginia 1 Alexander Chapter, Regent, Sarah Henze; President’s Corner DAR Mount Vernon Chapter, Regent, Katy Compatriots: Kane; NSSAR, C.A.R.–SAR Relations Committee Chairman, Darrin Schmidt; April was a very busy Col. William Grayson Chapter President, month for the Chapter to Mike Weyler; and Fairfax Resolves include the George Chapter, Past-President, Ken Bonner. Washington Chapter’s Guests of honor included Fairfax County 65th Anniversary Police, Master Police Officer, Kevin Webb; celebration, laying a JROTC Cadet, 1st Lt. Tyler Herod, and the wreath at James Monroe’s beloved Julia Carr, wife of Bob Carr, Past- 261st Birthday Celebration Ceremony, a President of the GW Chapter who passed Law Enforcement Commendation last year. In total we had over 30 guests in Ceremony and recognizing two Security attendance to be part of our Anniversary Access Control Officers who rendered celebration. timely assistance to a compatriot’s wife and were recognized with the Outstanding Notable George Washington Chapter Citizenship Award. Yep, we had a very Leaders included Past-VASSAR President busy month, so let’s get to the details. -

Albemarle County in Virginia

^^m ITD ^ ^/-^7^ Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.arGhive.org/details/albemarlecountyiOOwood ALBEMARLE COUNTY IN VIIIGIMIA Giving some account of wHat it -was by nature, of \srHat it was made by man, and of some of tbe men wHo made it. By Rev. Edgar Woods " It is a solemn and to\acKing reflection, perpetually recurring. oy tHe -weaKness and insignificance of man, tHat -wKile His generations pass a-way into oblivion, -with all tKeir toils and ambitions, nature Holds on Her unvarying course, and pours out Her streams and rene-ws Her forests -witH undecaying activity, regardless of tHe fate of Her proud and perisHable Sovereign.**—^e/frey. E.NEW YORK .Lie LIBRARY rs526390 Copyright 1901 by Edgar Woods. • -• THE MicHiE Company, Printers, Charlottesville, Va. 1901. PREFACE. An examination of the records of the county for some in- formation, awakened curiosity in regard to its early settle- ment, and gradually led to a more extensive search. The fruits of this labor, it was thought, might be worthy of notice, and productive of pleasure, on a wider scale. There is a strong desire in most men to know who were their forefathers, whence they came, where they lived, and how they were occupied during their earthly sojourn. This desire is natural, apart from the requirements of business, or the promptings of vanity. The same inquisitiveness is felt in regard to places. Who first entered the farms that checker the surrounding landscape, cut down the forests that once covered it, and built the habitations scattered over its bosom? With the young, who are absorbed in the engagements of the present and the hopes of the future, this feeling may not act with much energy ; but as they advance in life, their thoughts turn back with growing persistency to the past, and they begin to start questions which perhaps there is no means of answering. -

The Federalist (And Antifederalist) Review Guide

The Federalist (and Antifederalist) Review Guide The Federalist Papers were authored by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in the fall/winter of 1787-1788. Federalists believed in a strong central government and used the press to encourage ratification of the newly proposed Constitution through a series of “letters to the people” espousing (supporting) the virtues and protections the new document would give the American people as well as solve many of the problems of the Articles of Confederation. The letters were signed “Publius” which is Greek for “public.” Several of the papers are notable for their specific arguments on the importance of the newly created Constitution principles such as Federalism, checks & balances, limited government, and separation of powers. The Antifederalist Papers were written as a result of huge debate against ratifying the Constitution. Theses arguments appeared in various forms and by various authors. The authors used pseudonyms (fake names). While the authors of the Antifederalist Papers are not provided in any particular list, the major authors include Cato (likely George Clinton), Brutus (likely Robert Yates), Centinel (Samuel Bryan), and the Federal Farmer (either Melancton Smith, Richard Henry Lee, or Mercy Otis Warren). Other pseudonyms/authors include An Old Whig, Aristocrotis, Leonidas, Agrippa (John Winthrop), Candidus, A Customer, William Penn, Philadelphiensis, Richard Henry Lee, William Grayson and more. Patrick Henry’s speeches may also be considered as “Antifederalist” work. These papers contained warnings of dangers from tyranny that weaknesses in the proposed Constitution did not adequate protect against. Some of these dangers were corrected with the adoption of the Bill of Rights. -

Politics in a New Nation: the Early Career of James Monroe

72-15,198 DICKSON, Charles Ellis, 1935- POLITICS IN A NEW NATION: THE EARLY CAREER OF JAMES MONROE. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 History, modern University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Charles Ellis Dickson 1972 POLITICS IN A NEW NATION: THE EARLY CAREER OP JAMES MONROE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Charles Ellis Dickson, B.S., M.A. ###### The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by PLEASE NOTE: Some pages have indistinct print. Filmed as received. University Microfilms, A Xerox Education Company ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Among the many people who have helped me in my graduate studies at Ohio State, I wish in particular to thank my adviser, Professor Mary E. Young, and my wife, Patricia. This work is dedicated to my father, John McConnell Dickson (1896-1971). ii VITA 13 June 1935 . Born— Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 1957 ............. B.S., Indiana University of Penn sylvania, Indiana, Pennsylvania 1957-195 8 . Active Duty as Second Lieutenant, U.S.A.R., Port Lee, Virginia 1958-196 6 . Social Studies Teacher, Churchill Area Schools, Pittsburgh, Pennsyl vania 1961 ............. M.A., University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 196^ . Pulbright Grant for Study and Travel in Prance and Great Britain 1967-1970 . Teaching Associate, Department of History, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1970-Present . Assistant Professor, Department of History, Geneva College, Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania FIELDS OF STUDY Jefferson-Jackson. Professor Mary E. Young Colonial America. Professor Bradley Chapin and Assistant Professor Paul G. Bowers Tudor-Stuart. -

Colonel William Grayson Tomb Rededication

President’s Message January 2015 Compatriots, Happy New Year to each of you, and welcome to 2015. I hope you and your families enjoyed the blessings of the Christmas season and enter the New Year in good health. We have much to look forward to this year in our Chapter and in SAR. Upcoming Events: First, I am pleased to inform you of a $260 donation the Chapter was able to make to Fisher House in December. An anonymous January 29: benefactor funded our Christmas social on December 11, and ask Rumbaugh Orations that members who attended would make a $10 donation/per person to Fisher House. Thank you all who attended and for your February 7: response to the request of our benefactor. Colonel William Grayson Tomb Rededication (VASSAR) Second, be advised that all current Chapter Officers (including myself) have agreed to serve until May 2015. This is due to a February 12: number of pending (and necessary) amendments to our Chapter Board of Managers Meeting By-Laws. I felt that it would be less disruptive to Chapter operations if all Officers continued to serve in their current February 16: capacities until these changes had been finalized and approved at George Washington’s the April 2015 meeting. When I presented this approach to the Birthday Parade Chapter leadership in November 2014, they all agreed that we should proceed as I suggested. As a result, you can expect to February 20-22: receive more information about these changes in the coming days. VASSAR Annual Meeting The Chapter Constitution and By-Laws Committee has been formed and will begin its deliberations in January. -

The Life of John Marshall

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com ^V^YNBSdURG COLLEGE JUNIONTOWN CENTER THE LIFE OF JOHN MARSHALL &tanfcati> fti&rarp <2£iritton IN FOUR VOLUMES VOLUME I JOHN MARSHALL AT 43 From a miniature painted in Paris THE LIFE OF JOHN MARSHALL BY ALBERT J. BEVEEIDGE Volume I FBONTIERSMAN, SOLDIEB LAWMAKER 1755-1788 BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE ^IVERSITX COMMONWEALTH CAMPUSES LIBRARIES^ FAYETTE CAMPUS. — COPYIUOBT, I9I0, DT ALBERT J. BEVBMDGt IOIO, BY HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANV ALL RIGHTS RISEKVBD PREFACE The work of John Marshall has been of supreme importance in the development of the American Nation, and its influence grows as time passes. Less is known of Marshall, however, than of any of the great Americans. Indeed, so little has been written of his personal life, and such exalted, if vague, en comium has been paid him, that, even to the legal profession, he has become a kind of mythical being, endowed with virtues and wisdom not of this earth. He appears to us as a gigantic figure looming, indis tinctly, out of the mists of the past, impressive yet lacking vitality, and seemingly without any of those qualities that make historic personages intelligible to a living world of living men. Yet no man in our history was more intensely human than John Mar shall and few had careers so full of movement and color. His personal life, his characteristics and the incidents that drew them out, have here been set forth so that we may behold the man as he appeared to those among whom he lived and worked. -

NEH Application Cover Sheet Digital Projects for the Public

NEH Application Cover Sheet (MN-258857) Digital Projects for the Public: Production Grants PROJECT DIRECTOR Dr. Kelly Leahy Whitney E-mail: [email protected] Chief Product and Partnerships Officer Phone: (b) (6) 1035 Cambridge Street Fax: Cambridge, MA 02141-1057 USA Field of expertise: Digital Humanities INSTITUTION iCivics Cambridge, MA 02141-1057 APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Ratifying the Constitution: A Digital Game Opportunity Grant period: From 2018-01-01 to 2019-08-31 Project field(s): U.S. History; American Government; Law and Jurisprudence Description of project: iCivics, in collaboration with Filament Games and select scholars in the humanities, proposes to develop its 20th online educational video-game: "Ratification: The Great Debate.” The game will offer middle and high school students a new immersive experience on a pivotal topic: the ratification of the United States Constitution. Our goal is to impart students with core knowledge surrounding this eventful period, to develop their argumentative writing, and to give our thousands of teacher-users a unique resource to engage their students in our nation’s history. BUDGET Outright Request 400,000.00 Cost Sharing 0.00 Matching Request 0.00 Total Budget 400,000.00 Total NEH 400,000.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Mr. Gabriel Neher E-mail: [email protected] 1035 Cambridge Street Phone: 617-356-8311 ext.103 Cambridge, MA 02141-1057 Fax: USA Table of Contents Application Narrative A) Nature of the request . 1 B) Humanities content . 1 C) Project format . 8 D) Audience and distribution . 9 E) Project evaluation and testing . 10 F) Right, permissions, and licensing. 11 G) Humanities advisers . -

How Grayson Became Grayson

How Grayson became Grayson © Glen Haney 2007 The town of Grayson, Kentucky County seat of Carter, was named so in honor of Heabard (Grayson) Carter. She would be known as Hebe. It is hard to imagine anyone with a richer, blue blooded pedigree, than Hebe. Her grandmother was a cousin of James Monroe. Her mother, was a sister of Maryland Governor William Smallwood. Her nephew, was Confederate General John Breckenridge Grayson. Hebe, daughter of Col. William. Grayson and Miss. Smallwood, married Robert W. Carter(1), of Loudoun Co., Virginia about 1795. They had a fine estate in Virginia and life was good. It appears that Robert passed away around 1808 leaving six children. Hebe decided to move to Kentucky to work the huge 70,000 acre grant given to her father for his war service. The move was hardly a back- breaking affair, at least for Hebe and the family, as she brought along the slaves. The 1810 census shows that Hebe owns 12 slaves. In addition to the children, in the household there are seven other adult males and one female; most likely hired help and slave overseers. Two cousins of Hebe, Robert H. and George W., who apparently made the trip with her, own 49 and 5 slaves respectively. Even with the luxuries her position afforded her, the move from the soft life in a grand house in Virginia, to the backwoods of Kentucky, must have must have come after considerable contemplation. With the amount of baggage and bodies, it is most likely that that her party traveled first to Wheeling, Va. -

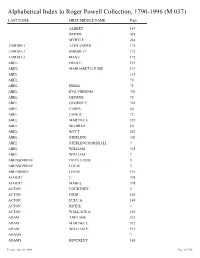

Alphabetical Index to Roger Powell Collection, 1790-1996 (M 037) LAST NAME FIRST/MIDDLE NAME Page

Alphabetical Index to Roger Powell Collection, 1790-1996 (M 037) LAST NAME FIRST/MIDDLE NAME Page ALBERT 147 BERTIE 424 MYRTLE 268 CORNELL ALEXANDER 172 CORNELL HARRIETT 172 CORNELL IRENE 172 ABEE FRED E. 139 ABEE MARGARET LOUISE 139 ABEL 318 ABEL 70 ABEL EMMA 72 ABEL EVA VIRGINIA 302 ABEL GEORGE 72 ABEL GEORGE F. 323 ABEL JAMES 60 ABEL JANE D. 72 ABEL MARTHA E. 323 ABEL MILDRED 60 ABEL ROY T. 253 ABEL STERLING 302 ABEL STERLING MARSHALL 7 ABEL WILLIAM 318 ABEL WILLIAM 7 ABENSCHIENE DEAN LOUIS 5 ABENSCHIENE LOUIS 5 ABENSHIEN LOUIS 110 ACHERT C. 398 ACHERT MABEL 398 ACTON COURTNEY 5 ACTON JOHN 150 ACTON LULU A. 169 ACTON RICH E. 3 ACTON WALLACE A. 150 ADAM ADELANE 512 ADAM MARTHA L. 512 ADAM WILLIAM F. 512 ADAMS 7 ADAMS BEVERLEY 160 Tuesday, June 02, 2009 Page 1 of 468 LAST NAME FIRST/MIDDLE NAME Page ADAMS CARLOS 512 ADAMS DELL 395 ADAMS EDITH 324 ADAMS EDWIN CARL 2 ADAMS ELIZ. 17 ADAMS ELLA 225 ADAMS ELLA 354 ADAMS ELLA 70 ADAMS F. MASON 160 ADAMS MARY T. 118 ADAMS O. BUFORD 188 ADIE FANNIE 149 ADIE FANNIE A. 142 ADIE FRANCES 189 ADIE FRANCES A. 179 ADIE JAMES 149 ADIE JENNIE 62 ADKINS DOROTHY 2 ADKINS LESTER ALFRED 2 ADLER MATILDA 161 ADLER MATILDA 169 ADLER MAURICE 169 ADLER MAURICE E. 161 ADLER MAURICE J. 161 ADLER MAURICE J. 169 ADRAIN 3 ADRAIN ADA 174 ADRAIN ADA CONSTANCE 417 ADRAIN ANNIE 3 ADRAIN DOROTHY ELIZ. 3 ADRAIN EDITH 7 ADRAIN EUGENE 152 ADRAIN EUGENE 5 ADRAIN EUGENE S. -

Prince William County, Virginia Court Orders 1783-1784

PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY, VIRGINIA COURT ORDERS 1783-1784 Transcribed by Kenna Cathcart Transcribed by RELIC volunteer Kenna Cathcart, from Prince William County Court Order Book 1778-1784, a continuation of transcriptions in Northern Virginia Genealogy, v. 5-9 (2000-2004). Ruth E. Lloyd Information Center (RELIC) Prince William Public Library System Bull Run Regional Library, Manassas, Virginia 2012 Prince William County, Virginia, Court Orders 1783-1784 [p. 200] December Court 1782 Court on Harriss At a court called and held at the court house for Prince William County the 10th day of December 1782 for the examination of Burr Harriss for felony. Present: Foushee Tebbs, William Carr, William Tebbs , Jesse Ewell Gent. Justices The said Burr Harriss being committed to the God of the said County by an order of the Court of the said County dated the Second Instant being charged with feloniously stealing and carrying away a parcel of yarn and thread and a pair of knee buckles from a certain John Ryner of which charge he said he is not guilty and the several Evidences being heard in behalf of the commonwealth and of the prisoner it is the opinion of the Court upon full testimony that his not guilty of the felony, but that he has been guilty of a breach of the peace and of a trespass in the taking of the goods from the said Ryner. The Court therefore order and direct that he stand committed until he gives security in the sum of one hundred pounds and his two security in the sum of fifty pounds each that he make his personal appearance at the next Grand Jury Court to beheld for this County to answer an indictment then to be presented against him for the aforesaid trespasses and that he do not depart thence without leave of the Court & be of good behaviour in the mean time. -

Read a More Comprehensive History of James Monroe Here

PRESIDENT JAMES MONROE Our country's fifth President, James Monroe endured the untimely loss of his parents, carried a musket and faced fierce fighting in the American Revolutionary War, took a bullet to the shoulder and grieved over the death of an infant son. Monroe's war time service was followed by nearly fifty years of public service. It is in those offices that he had a hand in shaping the nation, from conducting negotiations for land purchases which effectively doubled the size of the United States, to penning his Monroe Doctrine which opposed any further colonization by European powers in the western hemisphere, to helping the country avoid a sectional crisis with the Missouri Compromise. He was the most qualified man to ever assume the office, and he was a skilled farmer as well. It seemed there was nothing Monroe could not do. Revolutionary War Hero. Lawyer. State Legislator. Congressman. Senator. Diplomat. Governor of Virginia. Secretary of State. Secretary of War. President of the United States. “A better man cannot be.” - Thomas Jefferson, 1785 Introduction James Monroe was a deliberate thinker as well as a nationalist in diplomacy and defense. He supported a limited executive branch of the federal government and advocated that the needs of the public should be paramount over personal greed and party ambition. He extolled the advantages of farmers and craftsmen, and distrusted a vigorous central government in domestic affairs. Chapter 1: Monroe's Early Years James Monroe's mother Elizabeth Jones Monroe was pictured as “a very amiable and respectable woman, possessing the best domestic qualities of a good wife, and a good parent,” recounts Monroe. -

A Survey of Historic Architecture in Grayson County, Virginia Including the Towns of Independence and Fries

A Survey of Historic Architecture in Grayson County, Virginia including the towns of Independence and Fries Conducted for Virginia Department of Historic Resources Richmond, Virginia Conducted by Gibson Worsham, Architect Winter 2001 – Spring 2002 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 3 Acknowledgments 3 List of Figures 4 List of Plates 5 Introduction/Description of the Project Introduction 6 Description of Survey Area 7 Historic Context Introduction 9 Previously Identified Historic Resources 9 Historic Overview of the Survey Area 13 European Settlement to Society (1607-1752) 13 Colony to Early National Period (1753-1830) 14 Antebellum Period (1831-1860) 26 Civil War (1861-1865) 36 Reconstruction and Growth (1866-1916) 36 World War I to World War II (1917-1945) 53 The New Dominion (1946-Present) 60 Survey Results by Theme and Period 63 Research Design Introduction 72 Methodology 72 Expected Results 72 Survey Findings 73 Evaluation Potential Historic Designations and Boundaries 73 Eligibility Standards 74 Properties Eligible for Listing 77 Preservation Recommendations 79 Glossary 81 Bibliography 86 Appendices 88 Numerical Inventory of Surveyed Properties Alphabetical Inventory of Surveyed Properties 2 3 ABSTRACT Grayson County, Virginia, is a rural community in mountainous southwest Virginia within the primary service area of the Roanoke Regional Preservation Office (RRPO), a branch of the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR). The county had never been the subject of a coordinated survey effort. In winter-spring 2001-2002, Gibson Worsham surveyed 150 properties within the county to the Reconnaissance Level and 15 to the Intensive Level, including four sites that were resurveyed and are included in the indices and tabulations.