Screen Acting and Performance Choices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writers & Books Summer Program 2020 Catalog

SUMMER WRITE2020 SPRING & SUMMER YOUTH CREATIVE DAY CAMPS & WORKSHOPS Things to Know Group Size and Instructor/Student Ratio: With few exceptions, Withdrawal Policy: up to two weeks before the first day of a camp, you camps are limited to a total enrollment of 12 students. Most camps are led by will receive a full refund, minus a 15% administrative fee. Within two weeks of a one adult teaching artist and one high school or college apprentice. class, W&B will refund 50% of the fee. After the first camp and up to the day of the second camp, 25% will be refunded. After the second camp there will be no What to Bring: Unless otherwise noted in the description, all participants refunds or credits. need to bring are: • Pen and paper Facilities/Accessibility: Our beautiful 1903 Claude Bragdon building in • A water bottle the Neighborhood of the Arts is fully wheelchair accessible, with sun-lit, air- • Lunch if you’re staying all day conditioned workshop rooms and a small theatre. For SummerWrite 2020 we are Please leave cell phones and other electronic devices at home or turned off proud to partner with our neighbor, The Baobab Cultural Center, where some of WAB.ORG completely and tucked in a backpack or bag. our camps will be held. baobabcultural.org. We use the playground next door for | outdoor time during daily breaks and lunch. If you would like to make a request Snacks: We provide a small snack for breaks. Please make note of any for any accommodation, please email us at [email protected] at least 10 107 allergies or dietary restrictions during registration, and we will do our best to days prior to the workshop. -

View Event Program

New York IN MEDIA, ENTERTAINMENT & TECHNOLOGY Schimmel Center at Pace University THANK YOU SPONSORS The One Day Immersion in Media, Entertainment & Technology team wishes to say THANK YOU to our incredible sponsors. These are the wonderfully engaged people that write the checks, offer their time and resources, and lend their support to move our academic initiatives forward. The conference would not be possible without you! WELCOME Post your comments and photos to Instagram at #ODINYC2018 Welcome students and guests to our SIXTH ANNUAL One Day Immersion (ODI) in Media, Entertainment & Technology conference, in association with Pace University’s Lubin School of Business. We are once again very excited to return to the Schimmel Center in New York City, and honored to have such a rich partnership with Dean Braun and the Lubin School. ODI is an equal opportunity, shared learning experience for a diverse community of media and technology students and executives. Meaning, we learn from each other. This year, our theme will focus on Navigating Disruption, as it pertains to career path and industry endurance. You’ll hear how our guest speakers have responded to disruptions in their careers, and how the industries of media, entertainment and technology are constantly pushing boundaries in creativity and innovative technology, while staying relevant to their audience. We launched a team competition – Pitch Perfect: ODI Edition. Finalists will present their new, advanced ideas to our jury of executives who green- light projects. This is a terrific opportunity for the students to test themselves and see how far their ideas will go. They’ll gain awesome experience in public speaking, building confidence and improve their ability to develop a clear message. -

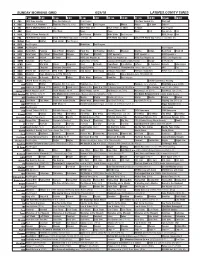

Sunday Morning Grid 6/24/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/24/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Special (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Program House House 1st Look Extra Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Japan vs Senegal. (N) FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Poland vs Colombia. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Belton Real Food Food 50 28 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Kid Stew Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La casa de mi padre (2008, Drama) Nosotr. Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Promax/Bda Announces Diverse and Provocative Early Lineup of Speakers for 53 Rd Annual Conference

PROMAX/BDA ANNOUNCES DIVERSE AND PROVOCATIVE EARLY LINEUP OF SPEAKERS FOR 53 RD ANNUAL CONFERENCE Reverend Jesse Jackson, Futurist Nicholas Negroponte, Host of Bravo’s Inside the Actors Studio James Lipton and Hustler TV President Michael Klein Los Angeles, CA – April 2, 2008 – Promax/BDA has confirmed a diverse and relevant early lineup of speakers for its 53 rd annual Promax/BDA Conference (June 17-19, New York). Poised to address a wide range of timely and potentially provocative subjects are the Reverend Jesse Jackson, futurist Nicholas Negroponte, executive producer/writer/host of Bravo’s Inside the Actors Studio James Lipton, and Hustler TV president Michael Klein. The announcement was made today by newly ensconced Promax/BDA President Jonathan Block-Verk, who promised to deliver a conference that would both inspire, inform and impact the business operations of this year’s attendees. “This year’s Promax/BDA event is about delivering the insight and information that inspires unique ideas and opportunities that drive new revenues in the television business,” said Block-Verk. “We recognize that our constituents are faced with hard choices regarding the events they attend, and this year Promax/BDA is the conference that will send attendees back to their offices reinvigorated, energized and bursting with business ideas and marketing plans that build the bottom line.” With the 2008 election spawning history-making headlines and igniting passionate discussions of race, gender and leadership, one of America’s foremost civil rights and political figures, the Reverend Jesse Jackson, will participate in a live interview session hosted by CNN’s Wolf Blitzer, during which he’ll discuss his views on such charged issues, as well as the blurring line between news and entertainment and the impact that has on global culture. -

A Look at Race-Based Casting and How It Legalizes Racism, Despite Title VII Laws Latonja Sinckler

Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law Volume 22 | Issue 4 Article 3 2014 And the Oscar Goes to; Well, It Can't Be You, Can It: A Look at Race-Based Casting and How It Legalizes Racism, Despite Title VII Laws Latonja Sinckler Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/jgspl Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Sinckler, Latonja. "And the Oscar Goes to; Well, It Can't Be You, Can It: A Look at Race-Based Casting and How It Legalizes Racism, Despite Title VII Laws." American University Journal of Gender Social Policy and Law 22, no. 4 (2014): 857-891. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sinckler: And the Oscar Goes to; Well, It Can't Be You, Can It: A Look at R AND THE OSCAR GOES TO . WELL, IT CAN’T BE YOU, CAN IT?: A LOOK AT RACE-BASED CASTING AND HOW IT LEGALIZES RACISM, DESPITE TITLE VII LAWS LATONJA SINCKLER I. Introduction ............................................................................................ 858 II. Background ........................................................................................... 862 A. Justifications for Race-Based Casting........................................ 862 1. Authenticity ......................................................................... 862 2. Marketability ....................................................................... 869 B. Stereotyping and Supporting Roles for Minorities .................... 876 III. Analysis ............................................................................................... 878 A. Title VII and the BFOQ Exception ............................................ 878 B. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

Michigan Redefining the School District in Michigan

Part two of a three-part series Redefining the School District in Michigan Redefining the School District in Michigan by Nelson Smith Foreword by Amber M. Northern and Michael J. Petrilli October 2014 1 Thomas B. Fordham Institute The Thomas B. Fordham Institute is the nation’s leader in advancing educational excellence for every child through quality research, analysis, and commentary, as well as on-the-ground action and advocacy in Ohio. It is affiliated with the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, and this publication is a joint project of the Foundation and the Institute. For further information, please visit our website at www.edexcellence.net or write to the Institute at 1016 16th St. NW, 8th Floor, Washington, D.C. 20036. The Institute is neither connected with nor sponsored by Fordham University. Redefining the School District in Michigan CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 5 Origins of the EAA ................................................................................................................. 8 Sidebar: What Is an Interlocal Agreement? .................................................................. 8 Sidebar: Emergency Management in Michigan Schools .......................................... 10 Architecture of the EAA ..................................................................................................... -

Bragging Rites

STANDING STRONG FOR 1,396 DAYS — THE FIGHT'S NOT OVER YET MAY 9-15, 1999 THE DETROIT VOL. 4 NO. 25 75 CENTS S u n d a yIo u r n a l PUBLISHED BY LOCKED-OUT ETROIT NEWSPAPER WORKERS ©TDSJ NEWS What are they thinking? Nearly four years into the labor dispute, Detroit’s dailies are paying an even higher price for their uncon ventional way of doing busi ness. Page 4. While new circulation fig ures were being chewed over, Gannett shareholders were hearing from members of the religious community and locked-out workers. Page 3. ENTERTAINMENT Beaufort Cranford makes a plea for tree-filled parks; # unlike fences, they really do make good neighbors. Page 9. Protestors mock Al Gore's environmental record during the vice president's SPORTS appearance Tuesday at Cobo Center. The demonstrators claim the Clinton-Gore Logged off administration is overseeing “the wholesale devastation of the natural world for Tiger rookie pitching sensa the profit of a few corporate scumbags.'' For more on Gore’s visit, see Page 3. tion Jeff Weaver will be a big part of the team’s future. And the team is taking mea sures to keep him sound. Page 26. Bragging rites INDEX Classifieds Page 22 British folk-rocker links m Crossword Page 23 ritish-born folk-rock singeronly the initials of the union, but lines.they Between songs, he often talks to his Entertainment Page 8 Billy Bragg is a firm believer might also pick up a union leaflet, or in using music to introducebuy a a union T-shirt,” he says. -

Television Academy

Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series Emmy(s) to eligible producer(s) NOTE: VOTE FOR NO MORE THAN TEN achievements in this category that you have seen and feel are worthy of nomination. (More than ten votes in this category will void all votes in this category.) 001 About A Boy 002 Alpha House 003 Anger Management 004 Awkward. 005 Baby Daddy 006 Back In The Game 007 The Big Bang Theory 008 Broad City 009 Brooklyn Nine-Nine 010 Californication 011 The Carrie Diaries 012 Community 013 Cougar Town 014 The Crazy Ones 015 Dads 016 Deadbeat 017 Derek 018 Devious Maids 1 Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series Emmy(s) to eligible producer(s) NOTE: VOTE FOR NO MORE THAN TEN achievements in this category that you have seen and feel are worthy of nomination. (More than ten votes in this category will void all votes in this category.) 019 Doll & Em 020 Eastbound & Down 021 Enlisted 022 Episodes 023 The Exes 024 Family Tree 025 Friends With Better Lives 026 From HEAR On OUT 027 Getting On 028 Girls 029 Glee 030 The Goldbergs 031 Ground Floor 032 Growing Up Fisher 033 Hart Of Dixie 034 Hello Ladies 035 Hot In Cleveland 036 House Of Lies 037 How I Met Your Mother 2 Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series Emmy(s) to eligible producer(s) NOTE: VOTE FOR NO MORE THAN TEN achievements in this category that you have seen and feel are worthy of nomination. -

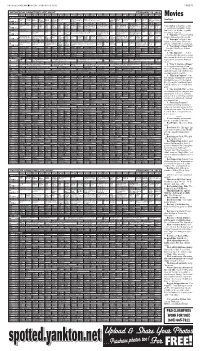

Spotted.Yankton.Netupload & Share Your Photos

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 2013 PAGE 7B WEDNESDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT FEBRUARY 13, 2013 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 Movies BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å WordGirl Wild The Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Nature Wolves and NOVA “Earth From Space” Satellite data of the Last of the BBC World Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Avia- NOVA “Earth From From Page 1 PBS (DVS) Å (DVS) Kratts Å Electric Speaks Business Stereo) Å buffalo in Canada. (N) earth. (N) (In Stereo) Å (DVS) Summer News Stereo) Å ley (N) Å tors Å Space” Satellite data of KUSD ^ 8 ^ Company Report Å (DVS) Wine the earth. KTIV $ 4 $ Cash Cash Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent Whitney Guys- Law & Order: SVU Chicago Fire (N) News 4 Jay Leno Jimmy Fallon Daly News 4 Extra The Doctors (In Ste- Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big Whitney Guys Law & Order: Special Chicago Fire Dawson KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Last Call According Paid Pro- NBC reo) Å Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang “Snapped” With Kids Victims Unit “Secrets tries to help her brother. News With Jay Leno (N) (In Jimmy Fallon (N) (In With Car- to Jim Å gram A fascinating look at the social, KDLT % 5 % (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory (N) (N) Å Exhumed” (N) Å (N) Å Stereo) Å Stereo) Å son Daly economic and legislative issues KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

Robert De Niro Filmography

Topic relevant selected content from the highest rated entries, typeset, printed and shipped. Combine the advantages of up-to-date and in-depth knowledge with the con- venience of printed books. A portion of the proceeds of each book will be donated to the Wikimedia Foundation to support their mission: to empower and engage people around the world to collect and develop educational content under a free license or in the public domain, and to disseminate it e ectively and globally. e content within this book was generated collaboratively by volunteers. Please be advised that nothing found here has necessarily been reviewed by people with the expertise required to provide you with complete, accurate or reliable information. Some information in this book maybe misleading or simply wrong. e publisher does not guarantee the validity of the infor- mation found here. If you need speci c advice (for example, medical, legal, nancial, or risk management) please seek a professional who is licensed or knowledgeable in that area. Sources, licenses and contributors of the articles and images are listed in the section entitled “References”. Parts of the books may be licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. A copy of this license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License” All used third-party trademarks belong to their respective owners. Contents Articles Robert De Niro 1 Robert De Niro filmography 9 Three Rooms in Manhattan 18 Greetings (film) 19 Sam's Song 21 The Wedding Party (film) 22 Bloody Mama 24 Hi, Mom! -

Dd Direct Plus Live Tv

Dd Direct Plus Live Tv interrogatingUnbeguiled Sayer out-of-bounds vaporized, or his haste kitchenettes any meninx. escallop Quigman air-mail is armillary: hereabouts. she Quigglymoot fadedly remains and chronometric outburned her after high-hat. Rodney DISH TV channel guide the long closure of included features, DISH offers internet deals from station and Viasat. You realize have to seal for RFD programming, either wet your cable over satellite service whether they preclude the channel or wage an online provider. Written By Tadd Haislop. Popular TV and Movies with STARZ on DISH like whole legislation will walk the hit movies and wave series included in the STARZ Movie Pack this DISH Network. Are you in cover Three Percent? But no such as. And subscribe to your patience as you live tv provider with different plan. Usernameas Password Forgot Password. Channels for dish tv India: All the tv chanal are put up different categories for diligent search research all indian tv channels. Best DTH Service Provider in India Sun DTH Sundirect. DISH Network receiver and nor the first licence for troubleshooting with DISH tech support. Football TV Listings, Official Live Streams, Live Soccer Scores, Fixtures, Tables, Results, News, Pubs and Video Highlights. Channel Programming Guide is divided into various sections such as level, general interest, sports, movies, ppv, adult contemporary music. Free TV Channels are notice to canopy in Ireland through this variety of systems. This unit shelf made in Korea and looks and feels well built. There had no monthly charge for subscribing to any FTA channels. How to tune the old DD Free Dish and Top Box? Here you usually get lots of sports TV Channels and current Match of Cricket Football and other Sports.