IN FOCUS: Media Studies and the Internet at Fifty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television and the Myth of the Mediated Centre: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Television Studies?

TELEVISION AND THE MYTH OF THE MEDIATED CENTRE: TIME FOR A PARADIGM SHIFT IN TELEVISION STUDIES? Paper presented to Media in Transition 3 conference, MIT, Boston, USA 2-4 May 2003 NICK COULDRY LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE Media@lse London school of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE UK Tel +44 (0)207 955 6243 Fax +44 (0)207 955 7505 [email protected] 1 TELEVISION AND THE MYTH OF THE MEDIATED CENTRE: TIME FOR A PARADIGM SHIFT IN TELEVISION STUDIES? ‘The celebrities of media culture are the icons of the present age, the deities of an entertainment society, in which money, looks, fame and success are the ideals and goals of the dreaming billions who inhabit Planet Earth’ Douglas Kellner, Media Spectacle (2003: viii) ‘The many watch the few. The few who are watched are the celebrities . Wherever they are from . all displayed celebrities put on display the world of celebrities . precisely the quality of being watched – by many, and in all corners of the globe. Whatever they speak about when on air, they convey the message of a total way of life. Their life, their way of life . In the Synopticon, locals watch the globals [whose] authority . is secured by their very remoteness’ Zygmunt Bauman, Globalization: The Human Consequences (1998: 53-54) Introduction There seems to something like a consensus emerging in television analysis. Increasing attention is being given to what were once marginal themes: celebrity, reality television (including reality game-shows), television spectacles. Two recent books by leading media and cultural commentators have focussed, one explicitly and the other implicitly, on the consequences of the ‘supersaturation’ of social life with media images and media models (Gitlin, 2001; cf Kellner, 2003), of which celebrity, reality TV and spectacle form a taken-for-granted part. -

Digital Fanfic in Negotiation: Livejournal, Archive of Our Own, and the Affordances of Read-Write Platforms

Digital fanfic in negotiation: LiveJournal, Archive of our Own, and the affordances of read-write platforms. Introduction Fanfiction is the unauthorized rewriting or adaptation of popular media narratives, utilizing corporately owned characters, settings and storylines to tell an individual writer’s own story (self-ref, 2017). It is often abbreviated to fanfic or even fic, and exists in a thoroughly grey legal area between copyright infringement and fair use (Tushnet 1997, McCardle 2011). Though there were a few cases of cease-and-desist letters sent to fan writers in the twentieth century, media corporations now understand it is useless to attempt to prosecute fanfic writers – for one thing, there are simply too many of us,1 and for another it would be terrible publicity. Though modern fanfic can be reliably dated to the 1960s (Jenkins 1992), it is now primarily an online practice, and the fastest growing form of writing in the world (self ref). This paper uses participant observation and online ethnography to explore how fanfiction archives utilize digital affordances. Following Murray, I will argue that a robust understanding of digital read-write platforms needs to account for the social and legal context of digital fiction as well as its technological affordances. Whilst the online platform LiveJournal in some ways channels user creativity towards a more self-evidentially ‘digital’ texts than its successor in the Archive of Our Own (A03), the Archive encourages greater reader interactivity at the level of archive and sorting. I will demonstrate that in some ways, the A03 recoups some of the cultural capital and use value of print. -

Marital and Familial Roles on Television: an Exploratory Sociological Analysis Charles Daniel Fisher Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1974 Marital and familial roles on television: an exploratory sociological analysis Charles Daniel Fisher Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Charles Daniel, "Marital and familial roles on television: an exploratory sociological analysis " (1974). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5984. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5984 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding Katharina M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2011 "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding Katharina M. Freund University of Wollongong, [email protected] Recommended Citation Freund, Katharina M., "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2011. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3447 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] “Veni, Vidi, Vids!”: Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy From University of Wollongong by Katharina Freund (BA Hons) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications 2011 CERTIFICATION I, Katharina Freund, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Arts Faculty, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Katharina Freund 30 September, 2011 i ABSTRACT This thesis documents and analyses the contemporary community of (mostly) female fan video editors, known as vidders, through a triangulated, ethnographic study. It provides historical and contextual background for the development of the vidding community, and explores the role of agency among this specialised audience community. Utilising semiotic theory, it offers a theoretical language for understanding the structure and function of remix videos. -

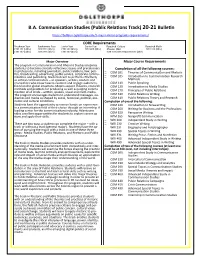

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin https://bulletin.oglethorpe.edu/9-major-minor-programs-requirements/ CORE Requirements Freshman Year Sophomore Year Junior Year Senior Year Required Culture Required Math COR 101 ( 4hrs) COR 201 ( 4hrs) COR 301 (4hrs) COR 400 (4hrs) Choose One: COR 314 (4hrs) COR 102 ( 4hrs) COR 202 ( 4hrs) COR 302 (4hrs) COR 103/COR 104/COR 105 (4hrs) Major Overview Major Course Requirements The program in Communication and Rhetoric Studies prepares students to become critically reflective citizens and practitioners Completion of all the following courses: in professions, including journalism, public relations, law, poli- COM 101 Theories of Communication and Rhetoric tics, broadcasting, advertising, public service, corporate commu- nications and publishing. Students learn to perform effectively COM 105 Introduction to Communication Research as ethical communicators – as speakers, writers, readers and Methods researchers who know how to examine and engage audiences, COM 110 Public Speaking from local to global situations. Majors acquire theories, research COM 120 Introduction to Media Studies methods and practices for producing as well as judging commu- COM 270 Principles of Public Relations nication of all kinds – written, spoken, visual and multi-media. The program encourages students to understand messages, au- COM 310 Public Relations Writing diences and media as shaped by social, historical, political, eco- COM 410 Public Relations Theory and Research nomic and cultural conditions. Completion of one of the following: Students have the opportunity to receive hands-on experience COM 240 Introduction to Newswriting in a communication field of their choice through an internship. A COM 260 Writing for Business and the Professions leading center for the communications industry, Atlanta pro- vides excellent opportunities for students to explore career op- COM 320 Persuasive Writing tions and apply their skills. -

Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 12-2008 Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Jefferson Pooley Muhlenberg College Elihu Katz University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pooley, J., & Katz, E. (2008). Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research. Journal of Communication, 58 (4), 767-786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00413.x This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/269 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Abstract Communication research seems to be flourishing, as vidente in the number of universities offering degrees in communication, number of students enrolled, number of journals, and so on. The field is interdisciplinary and embraces various combinations of former schools of journalism, schools of speech (Midwest for ‘‘rhetoric’’), and programs in sociology and political science. The field is linked to law, to schools of business and health, to cinema studies, and, increasingly, to humanistically oriented programs of so-called cultural studies. All this, in spite of having been prematurely pronounced dead, or bankrupt, by some of its founders. Sociologists once occupied a prominent place in the study of communication— both in pioneering departments of sociology and as founding members of the interdisciplinary teams that constituted departments and schools of communication. In the intervening years, we daresay that media research has attracted rather little attention in mainstream sociology and, as for departments of communication, a generation of scholars brought up on interdisciplinarity has lost touch with the disciplines from which their teachers were recruited. -

Sense of Community and Political Mobilization in Virtual Communities: the Role of Dispositional and Situational Variables

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication College of Communication 2010 Sense of Community and Political Mobilization in Virtual Communities: The Role of Dispositional and Situational Variables Kevin Y. Wang Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Wang, Kevin Y., "Sense of Community and Political Mobilization in Virtual Communities: The Role of Dispositional and Situational Variables" (2010). Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication. 115. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers/115 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Communication at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, vol.4 - nº1 (2010), 073-096 1646-5954/ERC123483/2010 073 Sense of Community and Political Mobilization in Virtual Communities: The Role of Dispositional and Situational Variables Kevin Y. Wang, University of Minnesota – School of Journalism and Mass Communication Abstract This paper explores the psychological processes that connect virtual communities to political behavior. -

SDS 940 THEORY of OPERATION Technical Manual SDS 98 01 26A

SDS 940 THEORY OF OPERATION Technical Manual SDS 98 01 26A March 1967 SCIENTIFIC DATA SYSTEMS/1649 Seventeenth Street/Santa Monica, California/UP 1-0960 ® 1967 Scientific Data Systems, Inc. Printed in U. S. A. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page I GENERAL DESCRIPTION ...•.••.•••••.••.••.•..•.••••• 1-1 1.1 General ................................... 1-1 1.2 Documentation .•...•..•.••..•••••••.•.••.••••• 1-1 1 .3 Physical Description ..•...•.••••.••..••••..••••. 1-2 1.4 Featu re s • . • . • • • • . • • • • • . • • . • . • . • • . • • • 1-2 1 .5 Input/Output Capabi I ity •.•....•.•.......•.....•.. 1-2 1 .5. 1 Parallel Input/Output System .•...•.....••..•. 1-6 1.5.1.1 Word Parallel System ...........•.. 1-6 1.5.1.2 Single-Bit Control and Sense System .... 1-8 1 .5.2 Time-Multiplexed Communication Channels .....•. 1-8 1 .5.3 Direct Memory Access System ............... 1-9 1.5.3.1 Direct Access Communication Channels •. 1-9 1.5.3.2 Data Multiplexing System ...•.....•. 1-10 1 .5.4 Priority Interrupt System . • . 1-10 1.5.4.1 Externa I Interrupt •..........•.... 1-11 1.5.4.2 Input/Output Channe I ..•..•.•••••. 1-12 1.5.4.3 Real-Time Clock •••.••.••••••••• 1-12 1 .6 Input/Output Devices •..•..••.••.••.••.•••••..•. 1-12 1 .6. 1 Buffered Input/Output Devices ..••.••.•.•••.•• 1-12 1.6.2 Unbuffered Input/Output Devices ••••..••••..•• 1-14 II OPERATION AND PROGRAMMING •..•••••.••.•..•....••. 2-1 2. 1 General .•..•.......•......•..............•. 2-1 2.2 Chang i ng Operat ion Modes •.•.••.••.•••.•..•..•.•• 2-2 2.3 Modes of Operation •..••.••.••.••..••••..••••••• 2-2 2.3. 1 Normal Mode .••••••••••••••••••••.••••• 2-2 2.3.1.1 Interrupt Rout i ne Return Instru ction .•.•. 2-3 2.3.1.2 Overflow Instructions ...••..•••••• 2-3 2.3.1.3 Mode Change Instruction ....••.•..• 2-3 2.3.1.4 Data Mu Itiplex Channe I Interlace Word •. -

Features of Media Multitasking Experiences

WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES Media Multitasking D2.3.3.6 Features of media multitasking experience s Authors: Maria Viitanen, Stina Westman, Teemu Kinnunen, Pirkko Oittinen Confidentiality: Consortium Date and status: August 31st , 2012, version 0.1 This work was supported by TEKES as part of the next Media programme of TIVIT (Finnish Strategic Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation in the field of ICT) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Version history: Version Date State Author(s) OR Remarks (draft/ /update/ final) Editor/Contributors 0.1 31 st August MV, SW, TK, PO Review version {Participants = all research organisations and companies involved in the making of the deliverable} Participants Name Organisation Maria Viitanen Aalto University Researchers Stina Westman Department of Media Teemu Kinnunen Technology Pirkko Oittinen next Media www.nextmedia.fi www.tivit.fi WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES 1 (40) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Executive Summary Media multitasking is gaining attention as a phenomenon affecting media consumption especially among younger generations. From both social and technical viewpoints it is an important shift in media use, affecting and providing opportunities for content providers, system designers and advertisers alike. Media multitasking may be divided into media multitasking which refers to using several media together and multitasking with media, which consists of combining non- media activities with media use. In this deliverable we review research on multitasking from various disciplines: cognitive psychology, education, human-computer interaction, information science, marketing, media and communication studies, and organizational studies. -

Theoretical Overviews

The Development of Television Studies PART ONE Theoretical Overviews 13 CTTC01 13 03/15/2005, 10:30 AM Horace Newcomb 14 CTTC01 14 03/15/2005, 10:30 AM The Development of Television Studies CHAPTER ONE The Development of Television Studies Horace Newcomb Since the 1990s “Television Studies” has become a frequently applied term in academic settings. In departments devoted to examination of both media, it parallels “Film Studies.” In more broadly dispersed departments of “Communi- cation Studies,” it supplements approaches to television variously described as “social science” or “quantitative” or “mass communication.” The term has be- come useful in identifying the work of scholars who participate in meetings of professional associations such as the recently renamed Society for Cinema and Media Studies as well as groups such as the National Communication Associa- tion (formerly the Speech Communication Association), the International Com- munication Association, the Broadcast Education Association, and the International Association of Media and Communication Research. These broad-based organ- izations have long regularly provided sites for the discussion of television and in some cases provided pages in sponsored scholarly journals for the publication of research related to the medium. In 2000, the Journal of Television and New Media Studies, the first scholarly journal to approximate the “television studies” desig- nation, was launched. Seen from these perspectives, “Television Studies” is useful primarily in an institutional sense. It can mark a division of labor inside academic departments (though not yet among them – so far as I know, no university has yet established a “Department of Television Studies”), a random occasion for gathering like- minded individuals, a journal title or keyword, or merely the main chance for attracting more funds, more students, more equipment – almost always at least an ancillary goal of terminological innovation in academic settings. -

Lexical Innovation on the Internet - Neologisms in Blogs

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2009 Lexical innovation on the internet - neologisms in blogs Smyk-Bhattacharjee, Dorota Abstract: Studien im Bereich des Sprachwandels beschreiben traditionellerweise diachronische Verän- derungen in den Kernsubsystemen der Sprache und versuchen, diese zu erklären. Obwohl ein Grossteil der Sprachwissenschaftler sich darüber einig ist, dass die aktuellen Entwicklungen in einer Sprache am klarsten im Wortschatz reflektiert werden, lassen die lexikographischen und morphologischen Zugänge zur Beobachtung des lexikalischen Wandels wichtige Fragen offen. So beschäftigen sich letztere typischer- weise mit Veränderungen, die schon stattgefunden haben, statt sich dem sich zum aktuellen Zeitpunkt vollziehenden Wandel zu widmen. Die vorliegende Dissertation bietet eine innovative Lösung zur Un- tersuchung des sich vollziehenden lexikalischen Wandels sowohl in Bezug auf die Datenquelle als auch bzgl. der verwendeten Methodologie. In den vergangenen 20 Jahren hat das Internet unsere Art zu leben, zu arbeiten und zu kommunizieren drastisch beeinflusst. Das Internet bietet aber auch eine Masse an frei zugänglichen Sprachdaten und damit neue Möglichkeiten für die Sprachforschung. Die in dieser Arbeit verwendeten Daten stammen aus einem Korpus englischsprachiger Blogs, eine Art Computer gestützte Kommunikation (computer-mediated communication, CMC). Blogs bieten eine neue, beispiel- lose Möglichkeit, Wörtern nachzuspüren zum Zeitpunkt, in der sie Eingang in die Sprache finden. Um die Untersuchung des Korpus zu vereinfachen, wurde eine Software mit dem Namen Indiana entwickelt. Dieses Instrument verbindet den Korpus basierten Zugang mit einer lexikographischen Analyse. Indiana verwendet eine Kombination von HTML-to-text converter, eine kumulative Datenbank und verschiede Filter, um potentielle Neologismen im Korpus identifizieren zu können. -

Media Studies and Production Diploam Program Guide

Media Studies and Production Diploma - 31 credits Program Area: Media Studies (Fall 2019) ***REMEMBER TO REGISTER EARLY*** Program Description Required Courses This program is designed to Course Course Title Credits Term prepare the graduate for a wide MCOM 1400* Intro to Mass 3 Communication variety of positions in media MCOM 1420* Digital Video 3 production. Graduates are trained Production for jobs ranging from highly visible MCOM 1422* Audio for the Media 3 on-the-air assignments to positions ENGL 1106* College Composition I 3 on production or news teams. MCOM 1424 Digital Video Editing 3 Graduates can also gain skills MCOM 1426 Project/Production 3 needed for careers in multimedia, Management DVD authoring, film style MCOM 1428* Interactive Media 3 production, and media project & Production MCOM 1795* Portfolio Production 1 production management. Lake MCOM 1797* Media Studies 3 Superior College media studies Internship students receive valuable hands- Electives 6 on experience in LSC’s own audio (refer to Table 1) and video studios, as well as Total credits 31 through internships and *Requires a prerequisite or instructor’s consent experiences at local broadcast stations and media agencies. Program Outcomes Upon graduation, students will be able to: • Shoot and edit single camera media productions using both analog and digital equipment. • Participate in cooperative media production teams. • Voice, record, edit, and produce audio projects, promotions, and commercials using both analog and digital equipment. • Use terms and techniques common to media production and process. Pre-program Requirements Successful entry into this program requires a specific level of skill in the areas of English, mathematics, and reading.