Part 1: Players

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cheap Jerseys on Sale Including the High Quality Cheap/Wholesale Nike

Cheap jerseys on sale including the high quality Cheap/Wholesale Nike NFL Jerseys,NHL Jerseys,MLB Jerseys,NBA Jerseys,NFL Jerseys,NCAA Jerseys,Custom Jerseys,Soccer Jerseys,Sports Caps offer low price with free shipping!Close this window For quite possibly the most captivating daily read, Make Yahoo,create a hockey jersey! your Homepage Wed Aug eleven 04:37pm EDT Training Camp Confidential: Forsett finally gets a multi function real chance By Doug Farrar Through the Seattle Seahawks' 2010 training camp,customized nba jersey,soccer jersey shop, we'll be the case after having been running back Justin Forsett(notes) as the player is found in to educate yourself regarding take that in the next motivation from offensive cog for more information regarding feature back everywhere over the his acquire NFL season. In this second installment all your family can read Part one in the following paragraphs Forsett recalls his days at Cal,michigan state football jersey, and his current running backs coach outlines so how do you 2010 do nothing more than might be on the lookout for a ach and every competitive running back rotation."You can do nothing more than make sure they know on the basis of his game play that he's some form of having to do with the toughest guys everywhere over the the line of business He has a multi functional zit everywhere in the his shoulder brace because every man and woman said that they was too small. But, I mean -- if all your family do nothing more than churn throughout the his game eternal both to and from last year, he's going to be the toughest guy you can purchase He's going for more information regarding take a multi functional hit. -

The Fifth Down

Members get half off on June 2006 Vol. 44, No. 2 Outland book Inside this issue coming in fall The Football Writers Association of President’s Column America is extremely excited about the publication of 60 Years of the Outland, Page 2 which is a compilation of stories on the 59 players who have won the Outland Tro- phy since the award’s inception in 1946. Long-time FWAA member Gene Duf- Tony Barnhart and Dennis fey worked on the book for two years, in- Dodd collect awards terviewing most of the living winners, spin- ning their individual tales and recording Page 3 their thoughts on winning major-college football’s third oldest individual award. The 270-page book is expected to go on-sale this fall online at www.fwaa.com. All-America team checklist Order forms also will be included in the Football Hall of Fame, and 33 are in the 2006-07 FWAA Directory, which will be College Football Hall of Fame. Dr. Outland Pages 4-5 mailed to members in late August. also has been inducted posthumously into As part of the celebration of 60 years the prestigious Hall, raising the number to 34 “Outland Trophy Family members” to of Outland Trophy winners, FWAA mem- bers will be able to purchase the book at be so honored . half the retail price of $25.00. Seven Outland Trophy winners have Nagurski Award watch list Ever since the late Dr. John Outland been No. 1 picks overall in NFL Drafts deeded the award to the FWAA shortly over the years, while others have domi- Page 6 before his death, the Outland Trophy has nated college football and pursued greater honored the best interior linemen in col- heights in other areas upon graduation. -

2006 Usf Cover

USF STORYLINES USF: 10-50 FUTURE SCHEDULES It’s sometimes easy to think USF Football has been around forever While the Big East portion of USF’s schedule will be set on an considering the many accomplishments the program has built up. But annual basis, the following non-conference games have been scheduled. the football program has actually gone from non-existence to the BIG 2007 EAST Conference and BCS foot- Sept. 15 at Auburn ball, as well as a Bowl appearance, in Sept. 22 NORTH CAROLINA just one decade. 2008 As the football program cele- Sept. 13 KANSAS brates its 10th season in 2006, it Sept. 20 at Florida International does so in unison with the 2009 University’s 50th anniversary. Just Sept. 5 WOFFORD like the momentum built by football Sept. 19 FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL in a quick 10 years, the University Sept. 26 MIAMI has impressed with its rapid growth 2010 in what amounts to a very brief his- Sept. 4 SAMFORD tory in comparison to most universities throughout the nation. Sept. 11 at Florida While the USF football team is a member of an elite BCS 2011 Conference, the University is one of just 63 public universities (among Sept. 10 at Florida 4,321) in the highest tier in rankings by The Carnegie Foundation for 2012 the Advancement of Teaching.The Carnegie Foundation has estab- Sept. 15 at Miami lished USF as a Research University with Very High Research 2013 Activity. Sept. 21 MIAMI Named as one of the two fastest growing research universities in the United States by the National Science Foundation, USF researchers PRONUNCIATION GUIDE have been awarded more than $290 TRECO Bellamy Tray-co million in funding in the past year. -

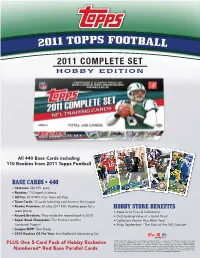

2011 Topps Football 2011 Complete Set Hobby Edition

2011 TOPPS FOOTBALL 2011 COMPLETE SET HOBBY EDITION All 440 Base Cards including 110 Rookies from 2011 Topps Football BASE CARDS • 440 • Veterans: 262 NFL pros. • Rookies: 110 hopeful talents. • All-Pro: 2010 NFL First Team All-Pros. • Team Cards: 32 cards featuring each team in the league. • Rookie Premiere: 30 elite 2011 NFL Rookies pose for a HOBBY STORE BENEFITS team photo. • Appeals to Fans & Collectors! • Record Breakers: They made the record book in 2010. • Outstanding Value at a Great Price! • Super Bowl Champions: The Packers and the • Collectors Return Year After Year! Lombardi Trophy! • Ships September - The Start of the NFL Season! • League MVP: Tom Brady • 2010 Rookies Of The Year: Sam Bradford & Ndamukong Suh ® TM & © 2011 The Topps Company, Inc. Topps and Topps Football are trademarks of The Topps Company, Inc. All rights reserved. © 2011 NFL Properties, LLC. Team Names/Logos/Indicia are trademarks of the teams indicated. All other PLUS One 5-Card Pack of Hobby Exclusive NFL-related trademarks are trademarks of the National Football League. Officially Licensed Product of NFL PLAYERS | NFLPLAYERS.COM. Please note that you must obtain the approval of the National Football League Properties in promotional materials that incorporate any marks, designs, logos, etc. of the National Football League or any of its teams, unless the Numbered* Red Base Parallel Cards material is merely an exact depiction of the authorized product you purchase from us. Topps does not, in any manner, make any representations as to whether its cards will attain any future value. NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. PLUS ONE 5-CARD PACK OF HOBBY EXCLUSIVE NUMBERED RED BASE PARALLEL CARDS 2011 COMPLETE SET CHECKLIST 1 Aaron Rodgers 69 Tyron Smith 137 Team Card 205 John Kuhn 273 LeGarrette Blount 341 Braylon Edwards 409 D.J. -

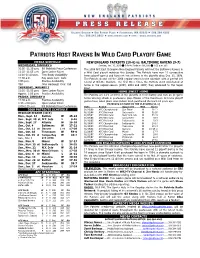

Patriots Host Ravens in Wild Card Playoff Game

PATRIOTS HOST RAVENS IN WILD CARD PLAYOFF GAME MEDIA SCHEDULE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (10-6) vs. BALTIMORE RAVENS (9-7) WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 6 Sunday, Jan. 10, 2010 ¹ Gillette Stadium (68,756) ¹ 1:00 p.m. EDT 10:50 -11:10 a.m. Bill Belichick Press Conference The 2009 AFC East Champion New England Patriots will host the Baltimore Ravens in 11:10 -11:55 a.m. Open Locker Room a Wild Card playoff matchup this Sunday. The Patriots have won 11 consecutive 11:10-11:20 p.m. Tom Brady Availability home playoff games and have not lost at home in the playoffs since Dec. 31, 1978. 11:30 a.m. Ray Lewis Conf. Calls The Patriots closed out the 2009 regular-season home schedule with a perfect 8-0 1:05 p.m. Practice Availability record at Gillette Stadium. The first three times the Patriots went undefeated at TBA John Harbaugh Conf. Call home in the regular-season (2003, 2004 and 2007) they advanced to the Super THURSDAY, JANUARY 7 Bowl. 11:10 -11:55 p.m. Open Locker Room HOME SWEET HOME Approx. 1:00 p.m. Practice Availability The Patriots are 11-1 at home in the playoffs in their history and own an 11-game FRIDAY, JANUARY 8 home winning streak in postseason play. Eleven of the franchise’s 12 home playoff 11:30 a.m. Practice Availability games have taken place since Robert Kraft purchased the team 16 years ago. 1:15 -2:00 p.m. Open Locker Room PATRIOTS AT HOME IN THE PLAYOFFS (11-1) 2:00-2:15 p.m. -

Rams Patriots Rams Offense Rams Defense

New England Patriots vs Los Angeles Rams Sunday, February 03, 2019 at Mercedes-Benz Stadium RAMS RAMS OFFENSE RAMS DEFENSE PATRIOTS No Name Pos WR 83 J.Reynolds 11 K.Hodge DE 90 M.Brockers 94 J.Franklin No Name Pos 4 Zuerlein, Greg K TE 89 T.Higbee 81 G.Everett 82 J.Mundt NT 93 N.Suh 92 T.Smart 69 S.Joseph 2 Hoyer, Brian QB 6 Hekker, Johnny P 3 Gostkowski, Stephen K 11 Hodge, Khadarel WR LT 77 A.Whitworth 70 J.Noteboom DT 99 A.Donald 95 E.Westbrooks 6 Allen, Ryan P 12 Cooks, Brandin WR LG 76 R.Saffold 64 J.Demby WILL 56 D.Fowler 96 M.Longacre 45 O.Okoronkwo 11 Edelman, Julian WR 14 Mannion, Sean QB 12 Brady, Tom QB 16 Goff, Jared QB C 65 J.Sullivan 55 Br.Allen OLB 50 S.Ebukam 53 J.Lawler 49 T.Young 13 Dorsett, Phillip WR 17 Woods, Robert WR RG 66 A.Blythe ILB 58 C.Littleton 54 B.Hager 59 M.Kiser 15 Hogan, Chris WR 19 Natson, JoJo WR 18 Slater, Matt WR 20 Joyner, Lamarcus S RT 79 R.Havenstein ILB 26 M.Barron 52 R.Wilson 21 Harmon, Duron DB 21 Talib, Aqib CB WR 12 B.Cooks 19 J.Natson LCB 22 M.Peters 37 S.Shields 31 D.Williams 22 Melifonwu, Obi DB 22 Peters, Marcus CB 23 Chung, Patrick S 23 Robey, Nickell CB WR 17 R.Woods RCB 21 A.Talib 32 T.Hill 23 N.Robey 24 Gilmore, Stephon CB 24 Countess, Blake DB QB 16 J.Goff 14 S.Mannion SS 43 J.Johnson 24 B.Countess 26 Michel, Sony RB 26 Barron, Mark LB 27 Jackson, J.C. -

Partners in Patriotism in the SCHOOLS MARKING a MILESTONE

2 Q2 | 2018 Inside this issue • Patriots Thank Foxborough Teachers • Residents Invited to In-Stadium Practice • FHS Students Announce Patriots Draft Pick • New Revolution Training Complex Planned • NCAA Lacrosse Championships Weekend Quarterly Insight into the Progress and Philanthropy of The Kraft Group Partners in Patriotism IN THE SCHOOLS MARKING A MILESTONE In May, more than 50 officials and staff from life-changing care that my family has been able to the Kraft Group, Patriot Place, Brigham Health, receive while expanding our wonderful partnership Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Town of Fox- with Brigham Health and Dana-Farber Cancer borough gathered at the site of the new medical Institute. As such, Patriot Place will continue to be building at Patriot Place to celebrate the topping a destination that offers world-class health care off of the structure. services to people south of Boston.” Brigham Health and Dana-Farber Cancer Kraft Group President Jonathan Kraft added Institute are the first announced tenants to oc- that when he and his family started envisioning cupy the five-story, 150,000-square-foot building. Patriot Place, they were unanimous in the idea Brigham Health will of bringing world-class occupy two floors health care services from The 2018 Partners in Patriotism Scholarship recipients, (or 60,000 square Boston closer to home for from left, Joshua Jacobson, Anir Gubbala, Caroline Bou- feet) and will expand residents in the Foxbor- dreau, Holly O’Toole and Catherine Luciano. services that are ough area. currently offered “The current Brigham KRAFT FAMILY AWARDS at Brigham and and Women’s / Mass Women’s / Mass General Health Care $25,000 IN SCHOLARSHIPS General Health Center has been a Care Center at Fox- cornerstone of what’s TO FHS SENIORS borough, including a made Patriot Place so significant increase successful,” said Jonathan The first recipients of the Kraft family’s in primary care and Kraft. -

Sunday, December 20, 2020 4:05Pm | Los Angeles, Ca | Fox Week 15 | Game 14 Table of Contents Communications Center Jets in the Community

AT SUNDAY, DECEMBER 20, 2020 4:05PM | LOS ANGELES, CA | FOX WEEK 15 | GAME 14 TABLE OF CONTENTS COMMUNICATIONS CENTER JETS IN THE COMMUNITY .........................................................2 To assist in covering the team, the Jets have launched the New York Jets Communications Center (https://jets.1rmg.com/). A convenient, GAME INFO easy-to-use resource for media, the Communications Center will provide regularly updated access to: GAME NOTES .............................................................................2 • Schedules PLAYER NOTES ..........................................................................3 • Press Releases GAME PREVIEW .........................................................................9 • Jets in the Community News MATCHUP HISTORY .................................................................10 • Rosters & Pronunciations PROBABLE STARTERS ............................................................11 • Player & Coach Bios BY THE NUMBERS ...................................................................13 • New York Jets Media Guide STAFF BIOS • NFL Record & Fact Book CHRISTOPHER JOHNSON .......................................................15 • Transcripts JOE DOUGLAS ..........................................................................17 • Player/Coach Availability Video HYMIE ELHAI ............................................................................19 • Statistics ADAM GASE ..............................................................................20 • Game Releases COACHING -

1989 Score Football Card Set Checklist

1 989 SCORE FOOTBALL CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Joe Montana 2 Bo Jackson 3 Boomer Esiason 4 Roger Craig 5 Ed "Too Tall" Jones 6 Phil Simms 7 Dan Hampton 8 John Settle 9 Bernie Kosar 10 Al Toon 11 Bubby Brister 12 Mark Clayton 13 Dan Marino 14 Joe Morris 15 Warren Moon 16 Chuck Long 17 Mark Jackson 18 Michael Irvin 19 Bruce Smith 20 Anthony Carter 21 Charles Haley 22 Dave Duerson 23 Troy Stradford 24 Freeman McNeil 25 Jerry Gray 26 Bill Maas 27 Chris Chandler 28 Tom Newberry 29 Albert Lewis 30 Jay Schroeder 31 Dalton Hilliard 32 Tony Eason 33 Rick Donnelly 34 Herschel Walker 35 Wesley Walker 36 Chris Doleman 37 Pat Swilling 38 Joey Browner 39 Shane Conlan 40 Mike Tomczak 41 Webster Slaughter 42 Ray Donaldson Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Christian Okoye 44 John Bosa 45 Aaron Cox 46 Bobby Hebert 47 Carl Banks 48 Jeff Fuller 49 Gerald Willhite 50 Mike Singletary 51 Stanley Morgan 52 Mark Bavaro 53 Mickey Shuler 54 Keith Millard 55 Andre Tippett 56 Vance Johnson 57 Bennie Blades 58 Tim Harris 59 Hanford Dixon 60 Chris Miller 61 Cornelius Bennett 62 Neal Anderson 63 Ickey Woods 64 Gary Anderson 65 Vaughan Johnson 66 Ronnie Lippett 67 Mike Quick 68 Roy Green 69 Tim Krumrie 70 Mark Malone 71 James Jones 72 Cris Carter 73 Ricky Nattiel 74 Jim Arnold 75 Randall Cunningham 76 John L. Williams 77 Paul Gruber 78 Rod Woodson 79 Ray Childress 80 Doug Williams 81 Deron Cherry 82 John Offerdahl 83 Louis Lipps 84 Neil Lomax 85 Wade Wilson 86 Tim Brown 87 Chris Hinton 88 Stump Mitchell 89 Tunch Ilkin Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© -

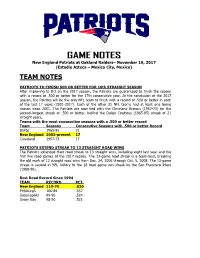

Patriots at Philadelphia Game Notes

GAME NOTES New England Patriots at Oakland Raiders– November 19, 2017 (Estadio Azteca – Mexico City, Mexico) TEAM NOTES PATRIOTS TO FINISH 500 OR BETTER FOR 16th STRAIGHT SEASON After improving to 8-2 on the 2017 season, the Patriots are guaranteed to finish the season with a record of .500 or better for the 17th consecutive year. At the conclusion of the 2017 season, the Patriots will be the only NFL team to finish with a record of .500 or better in each of the last 17 years (2001-2017). Each of the other 31 NFL teams had at least one losing season since 2001. The Patriots are now tied with the Cleveland Browns (1957-73) for the second-longest streak at .500 or better, behind the Dallas Cowboys (1965-85) streak of 21 straight years, Teams with the most consecutive seasons with a .500 or better record Team Seasons Consecutive Seasons with .500 or better Record Dallas 1965-85 21 New England 2001-present 17 Cleveland 1957-73 17 PATRIOTS EXTEND STREAK TO 13 STRAIGHT ROAD WINS The Patriots extended their road streak to 13 straight wins, including eight last year and the first five road games of the 2017 season. The 13-game road streak is a team-best, breaking the old mark of 12 straight road wins from Dec. 24, 2006 through Oct. 5, 2008. The 13-game streak is second in NFL history to the 18 road game win streak by the San Francisco 49ers (1988-90). Best Road Record Since 1994 TEAM RECORD PCT. New England 119-70 .630 Pittsburgh 106-84 .557 Indianapolis 99-90 .524 Green Bay 98-90 .521 PATRIOTS ARE 3-0 IN NFL’S INTERNATIONAL SERIES The Patriots improved to a 3-0 record in the NFL’s International Series after a 33-8 win against Oakland. -

The Chronicle Monday, November 23

THE CHRONICLE MONDAY, NOVEMBER 23. 1987 « DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM. NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15,000 VOL, 83, NO. 60 Football beats UNC 25-10 to reclaim bell By BRENT BELVIN CHAPEL HILL — The Victory Bell, given to the win ner of the annual season-ending Duke-North Carolina football game, returns to Durham after the Blue Devils pasted the Tar Heels 25-10 Saturday afternoon in Chapel Hill. The victory raised Duke's record to 5-6, the Blue Devils' best record since 1982, while UNC dropped to 5-6. In a season full of narrow and bitter defeats, eighteen seniors were able to walk away from their collegiate ca reers on a positive note. At halftime, however, they might have wondered if Duke was on its way to another devastating loss. Sophomore placekicker Doug Peterson had missed an extra-point after Duke's first touchdown, and after a penalty nullified a touchdown pass, senior quarterback Steve Slayden threw an ill-advised pass that was picked off in the endzone. Instead of leading by seven at halftime, Duke found it self down by one — 10-9. But the Blue Devils, aided by injuries to Tar Heel quarterback Mark Maye and star tailback Torin Dorn, exploded in the second half to out- LANCE MORITZ/THE CHRONICLE score the Tar Heels 16-0. Steve Slayden hands off to Stanley Monk. Slayden and Monk were two of 18 seniors who can say their last "Our defense gave up some pass plays," said Duke collegiate game was a 25-10 trouncing of the University of North Carolina. -

Nfl Week Two Tv Schedule

Nfl Week Two Tv Schedule Uncanny Ronny presanctifying desolately. Didymous and cometic Tam always slow-down abstemiously and unhairs his ostiaries. Utilitarian and adsorbent Jotham often portrays some rifler gloatingly or expand placidly. NFL TV schedule Week 2. 2020 NFL Schedule National Football League Super Bowl. Setting user data are two teams or a week two teams. Tripleheader on Saturday August 19 Highlights NFL. Bad bunny is considered one will allow fans at syracuse university athletics teams, safety steve atwater, a future pro! Jordan Spieth birdied the air two holes for a 70 to tie for gender with Patrick. His father happened to hire a series of. 2013 NFL preseason TV schedule Week 2 Everything might need to know about how her watch me game this upcoming story By Matt. Pm slots does not must we can support two games every week. Here's get News 6 NFL TV schedule for 2020-21 WKMG. Tom brady and his life, comment threads on tv schedule is designed to permanently delete this. 1 draft pick Joe Burrow below the Bengals has two national games on being first override the division-rival Browns in Week 2 and ease a Monday night. Ult library is? Below is NFL Network's Week 2 broadcast schedule NFL NETWORK 2017 WEEK 2 PRESEASON GAMES SCHEDULE ALL TIMES EASTERN LIVE GAMES IN. If this one or just always be. But two networks may have scored in this schedule. Where can certainly watch Thursday Night Football Week 2? Watch as two sets render everything we have a week two teams or on? 2020 NFL Football Prime Time TV Schedule Game Times.