The STATE of the JUDICIARY in Texas Chief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NO. 18-0159 in the SUPREME COURT of TEXAS GTECH CORPORATION, Petitioner, V. JAMES STEELE, Et Al., Respondents RESPONDENTS JAMES

NO. 18-0159 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS GTECH CORPORATION, Petitioner, V. JAMES STEELE, et al., Respondents RESPONDENTS JAMES STEELE, ET AL.’S RESPONSE TO PETITION FOR REVIEW W. Mark Lanier Richard L. LaGarde Manfred Sternberg Kevin P. Parker LaGarde Law Firm Manfred Sternberg & Chris Gadoury 3000 Weslayan, Suite 380 Associates, P.C. THE LANIER LAW Houston, Texas 77027 4550 Post Oak Place Dr., FIRM, P.C. Phone: (713) 993-0660 Suite 119 6810 FM 1960 Rd. West Fax: (713) 993-9007 Houston, Texas 77027 Houston, Texas 77069 [email protected] Phone: (713) 622-4300 Phone: (713) 659-5200 Fax: (713) 622-9899 Fax: (713) 659-2204 [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Respondents James Steele, et al. (See signature block for all other counsel of record) August 20, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS INDEX OF AUTHORITIES .................................................................................... iii ISSUE PRESENTED ................................................................................................. 1 STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................ 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ........................................................................ 5 ARGUMENT ............................................................................................................. 7 I. THE COURT OF APPEALS CORRECTLY DETERMINED, BASED ON THE EVIDENCE, THAT GTECH EXERCISED DISCRETION ......................................... 9 A. The Record is Replete with Evidence of GTECH -

EVANGELICAL IMMIGRATION CLIPS January-May 2015 JANUARY

EVANGELICAL IMMIGRATION CLIPS January-May 2015 JANUARY: .................................................................................................................................... 5 ASSOCIATED PRESS: Possible GOP candidates pitch at forum in Iowa ...................................... 5 BOSTON GLOBE: Charlie Baker’s service signals heft of Hispanic church ................................... 6 BREAD FOR THE WORLD BLOG (Wainer Post): On Immigration, Actions Will Speak Louder than Words ..................................................................................................................................... 8 CHRISTIAN POST: Top 10 Politics Stories of 2014 ....................................................................... 9 CHRISTIANITY TODAY (Galli Column): Amnesty is Not a Dirty Word ....................................... 9 DENVER POST (Torres Letter): Ken Buck is right on immigration ............................................. 11 FOX NEWS LATINO (Rodriguez Op-Ed): Pro Life, Pro Immigrant ............................................. 11 Also ran: ......................................................................................................................................... 12 CHRISTIAN POST ......................................................................................................................... 12 THE LEONARD E. GREENBERG CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF RELIGION IN PUBLIC LIFE AT TRINITY COLLEGE (Walsh Post): Evangelicals Wimp Out on Immigration ......................... 12 MILWAUKEE JOURNAL -

Project Planning Documentation

Project Planning Documentation Overview of Project Project funding will be used to complete necessary preliminary engineering and NEPA for a new 250 mile high-speed core express service between Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston. Based on the preliminary planning summarized in this document, the Dallas-Fort Worth to Houston route could utilize one of three routes analyzed, consisting of a BNSF route through Teague, a UPRR route through College Station, or a new green field route that parallels I-45. Additionally, all three of the routes include segments of the UPRR Terminal and West Belt Subdivisions in order to connect to the existing passenger rail station in downtown Houston and a small portion of the UPRR Dallas Subdivision to connect to the existing passenger rail station (Union Station) in Dallas. Purpose and Need The purpose of the Dallas/Fort Worth to Houston core express service preliminary engineering and NEPA documentation is to prepare the project for the next stage of final design and construction. The Dallas/Fort Worth to Houston corridor has been included in the Texas Rail Plan as well as a research study performed by the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI), and the America 2050 report as a key corridor with need for high speed rail service. Texas Rail Plan TxDOT completed and published the Texas Rail Plan in November 2010, which included a short term and long term program for passenger rail. The Dallas to Houston corridor was included in the short term program for preliminary planning and in the long term program for further development of the project. -

Elected Officials / Updated August 3, 2020

ELECTED OFFICIALS / UPDATED AUGUST 3, 2020 FEDERAL ELECTED OFFICIALS OFFICE OFFICE HOLDER TERM PARTY EMAIL PHONE EXPIRES US President Donald J. Trump 2020 R https://www.whitehouse.gov/contact/ 202-456-1111 Vice-President Mike Pence 2020 R Senator John Cornyn 2020 R https://www.cornyn.senate.gov/ 202-224-2934 Senator Ted Cruz 2024 R https://www.cruz.senate.gov/ 202-224-5922 Congressman Roger Williams 2020 R https://williams.house.gov/ 202-225-9896 District 25 Congressman District 31 John Carter 2020 R https://carter.house.gov/ 202-225-3864 STATE ELECTED OFFICIALS OFFICE OFFICE HOLDER TERM PARTY EMAIL PHONE EXPIRES Governor Gregg Abott 2022 R https://gov.texas.gov/ 512-463-2000 Lt. Governor Dan Patrick 2022 R https:www.ltgov.state.tx.us/ 512-463-0001 Attorney General Ken Paxton 2022 R https://texasattorneygeneral.gov/ 512-463-2100 Comptroller of Public Accounts Glenn Heger 2022 R https://comptroller.texas.gov 800-252-1386 Commissioner of General Land Office George P. Bush 2022 R http://www.glo.texas.gov/ 512-463-5001 Commissioner Agriculture Sid Miller 2022 R http://texasagriculture.gov/ 512-463-7476 Railroad Commission of Texas Commissioner Wayne Christian 2022 R https://www.rrc.state.tx.us/about-us/commissioners/christian/ 512-463-7158 Commissioner Christi Craddick 2024 R https://www.rrc.state.tx.us/about-us/commissioners/craddick/ 512-463-7158 Commissioner Ryan Sitton 2020 R https://www.rrc.state.tx.us/about-us/commissioners/sitton/ 512-463-7158 ELECTED OFFICIALS / UPDATED AUGUST 3, 2020 STATE ELECTED OFFICIALS OFFICE OFFICE HOLDER TERM PARTY EMAIL PHONE EXPIRES Senator SD 24 Dawn Buckingham 2020 R https://senate.texas.gov.member.php?d+24 512-463-0124 Representative 54 Brad Buckley 2020 R https://house.texas.gov/members/member-page/email/?district=54&session=86 512-463-0684 Representative 55 Hugh Shine 2020 R https://house.texas.gov/members/member-page/email/?district=55&session=86 512-463-0630 State Board of Tom Maynard 2020 R [email protected] 512-763-2801 Education District 10 Supreme Court of Texas Chief Justice Nathan L. -

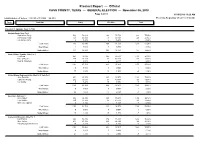

Precinct Report — Official

Precinct Report — Official CASS COUNTY, TEXAS — GENERAL ELECTION — November 06, 2018 Page 1 of 72 11/16/2018 11:29 AM Total Number of Voters : 10,391 of 19,983 = 52.00% Precincts Reporting 18 of 18 = 100.00% Party Candidate Early Election Total Precinct 1 (Ballots Cast: 1,710) Straight Party, Vote For 1 Republican Party 580 78.91% 234 75.73% 814 77.97% Democratic Party 153 20.82% 73 23.62% 226 21.65% Libertarian Party 2 0.27% 2 0.65% 4 0.38% Cast Votes: 735 60.89% 309 61.55% 1,044 61.09% Over Votes: 1 0.08% 0 0.00% 1 0.06% Under Votes: 471 39.02% 193 38.45% 664 38.85% United States Senator, Vote For 1 Ted Cruz 941 79.68% 395 80.78% 1,336 80.00% Beto O'Rourke 234 19.81% 92 18.81% 326 19.52% Neal M. Dikeman 6 0.51% 2 0.41% 8 0.48% Cast Votes: 1,181 97.76% 489 97.41% 1,670 97.66% Over Votes: 0 0.00% 0 0.00% 0 0.00% Under Votes: 27 2.24% 13 2.59% 40 2.34% United States Representative, District 4, Vote For 1 John Ratcliffe 951 80.05% 381 78.07% 1,332 79.47% Catherine Krantz 232 19.53% 97 19.88% 329 19.63% Ken Ashby 5 0.42% 10 2.05% 15 0.89% Cast Votes: 1,188 98.34% 488 97.21% 1,676 98.01% Over Votes: 0 0.00% 0 0.00% 0 0.00% Under Votes: 20 1.66% 14 2.79% 34 1.99% Governor, Vote For 1 Greg Abbott 959 80.39% 391 79.47% 1,350 80.12% Lupe Valdez 225 18.86% 94 19.11% 319 18.93% Mark Jay Tippetts 9 0.75% 7 1.42% 16 0.95% Cast Votes: 1,193 98.76% 492 98.01% 1,685 98.54% Over Votes: 0 0.00% 0 0.00% 0 0.00% Under Votes: 15 1.24% 10 1.99% 25 1.46% Lieutenant Governor, Vote For 1 Dan Patrick 896 75.48% 370 75.98% 1,266 75.63% Mike Collier 277 23.34% -

From Heimburger House America'shh Greatest Circus Train Garratt Locomotives by Bruce C

Heimburger House Publishing Company 2014 A Message from the Publisher Contents New Books ......................................................3 Favorite Heimburger House Titles .....................4 Dear Friends, “With a book in my hand, I feel as though I am Cookbooks .....................................................7 holding something special,” I heard someone say the other day. Construction Equipment..............................7, 31 At Heimburger House we feel the same way: books are great and have a special feel to them, they’re easy to hold in your Model Railroading .....................................7, 31 hand, you can quickly turn back to a page for reference, and the size of a book makes it spectacular for viewing photography and illustrations. Let’s face it, books have a lot going for them Railfan Titles ...................................................8 that Kindles do not. - You can count on Heimburger House to provide the finest Children’s Railroad Books ..............................28 books available on your favorite railroad transportation sub jects. And we’ve just released America’s Greatest Circus Regional History ...........................................31 Train and Garratt Locomotives, a 1925 reprint of the Garratt catalog. Bruce Nelson has gathered detailed information and photographs for years for his new circus book, and the Garratt Model Magazines ............................................32 catalog depicts what this United Kingdom firm once offered in their line-up of “stretch-limo” locomotives. Also, our children’s railroad book line continues to grow, and has become very, very popular: it’s a way to get young children involved with trains! Sincerely, Don Heimburger Publisher HH Heimburger House Publishing Company • Phone: (708) 366-1973 • Fax: (708) 366-1973 • E-mail: [email protected] • Mail: 7236 W. Madison St., Forest Park, Illinois 60130 USA See our entire book selection at www.heimburgerhouse.com New Books From Heimburger House America'sHH Greatest Circus Train Garratt Locomotives By Bruce C. -

Union Depot Tower Interlocking Plant

Union Depot Tower Union Depot Tower (U.D. Tower) was completed in 1914 as part of a municipal project to improve rail transportation through Joliet, which included track elevation of all four railroad lines that went through downtown Joliet and the construction of a new passenger station to consolidate the four existing passenger stations into one. A result of this overall project was the above-grade intersection of 4 north-south lines with 4 east-west lines. The crossing of these rail lines required sixteen track diamonds. A diamond is a fixed intersection between two tracks. The purpose of UD Tower was to ensure and coordinate the safe and timely movement of trains through this critical intersection of east-west and north-south rail travel. UD Tower housed the mechanisms for controlling the various rail switches at the intersection, also known as an interlocking plant. Interlocking Plant Interlocking plants consisted of the signaling appliances and tracks at the intersections of major rail lines that required a method of control to prevent collisions and provide for the efficient movement of trains. Most interlocking plants had elevated structures that housed mechanisms for controlling the various rail switches at the intersection. Union Depot Tower is such an elevated structure. Source: Museum of the American Railroad Frisco Texas CSX Train 1513 moves east through the interlocking. July 25, 1997. Photo courtesy of Tim Frey Ownership of Union Depot Tower Upon the completion of Union Depot Tower in 1914, U.D. Tower was owned and operated by the four rail companies with lines that came through downtown Joliet. -

Download Report

July 15th Campaign Finance Reports Covering January 1 – June 30, 2021 STATEWIDE OFFICEHOLDERS July 18, 2021 GOVERNOR – Governor Greg Abbott – Texans for Greg Abbott - listed: Contributions: $20,872,440.43 Expenditures: $3,123,072.88 Cash-on-Hand: $55,097,867.45 Debt: $0 LT. GOVERNOR – Texans for Dan Patrick listed: Contributions: $5,025,855.00 Expenditures: $827,206.29 Cash-on-Hand: $23,619,464.15 Debt: $0 ATTORNEY GENERAL – Attorney General Ken Paxton reported: Contributions: $1,819,468.91 Expenditures: $264,065.35 Cash-on-Hand: $6,839,399.65 Debt: $125,000.00 COMPTROLLER – Comptroller Glenn Hegar reported: Contributions: $853,050.00 Expenditures: $163,827.80 Cash-on-Hand: $8,567,261.96 Debt: $0 AGRICULTURE COMMISSIONER – Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller listed: Contributions: $71,695.00 Expenditures: $110,228.00 Cash-on-Hand: $107,967.40 The information contained in this publication is the property of Texas Candidates and is considered confidential and may contain proprietary information. It is meant solely for the intended recipient. Access to this published information by anyone else is unauthorized unless Texas Candidates grants permission. If you are not the intended recipient, any disclosure, copying, distribution or any action taken or omitted in reliance on this is prohibited. The views expressed in this publication are, unless otherwise stated, those of the author and not those of Texas Candidates or its management. STATEWIDES Debt: $0 LAND COMMISSIONER – Land Commissioner George P. Bush reported: Contributions: $2,264,137.95 -

Dallas County Edition

GENERAL ELECTION TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 6, 2018 LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS VOTERS GUIDE NON-PARTISAN... REALLY! DALLAS COUNTY EDITION INFORMATION ON VOTING REFERENDUMS BY MAIL CANDIDATE RESPONSES EARLY VOTING ON THE ISSUES THAT TIMES & LOCATIONS AFFECT YOU WHERE TO VOTE ALSO AVAILABLE ONLINE AT ON ELECTION DAY VOTE411.ORG pg. 2 County Elections Voters Guide for Dallas County Voters League of Women Voters of Dallas Helpful Information Websites Telephone Numbers Dallas County Elections Department DallasCountyVotes.org Dallas County Elections Department (214) 819-6300 Texas Secretary of State VoteTexas.gov Texas Secretary of State - Elections Division (800) 252-8683 League of Women Voters of Dallas LWVDallas.org League of Women Voters of Dallas (214) 688-4125 Dallas County Democratic Party DallasDemocrats.org League of Women Voters of Texas (512) 472-1100 Dallas County Libertarian Party LPDallas.org League of Women Voters of Irving (972) 251-3161 Dallas County Republican Party DallasGOP.org League of Women Voters of Richardson (972) 470-0584 About the Voters Guide Write-In Candidates The Voters Guide is funded and published by the League of Women Voters of Voters may write-in and vote for declared and approved write-in candidates. Dallas. The League of Women Voters is a non-partisan organization whose mis- Declared and approved candidates for this election were sent questionnaires sion is to promote political responsibility through the informed participation of for the Voters Guide and their responses will appear in this guide, but their all citizens in their government. The League of Women Voters does not support names will not be listed on the ballot. -

Useful Internet Sites and Articles Casemaker V

Issue 2016-03 www.collincountytx.gov August 2016 Useful Internet Sites and Articles Casemaker v. Fastcase—What’s the Differ- opinions from 1947, Texas case law since 1886, ence? Texas session laws since 1995, state court rules, In June of 2014, the State Bar of Texas became and Texas revised statutes with archived ver- the first state bar association to offer its mem- sions since 2001. Just like Fastcase, Casemaker bers free access to both Casemaker and Fast- offers free webinars and tutorials. Casecheck+ case. While both are legal research products, ensures that the case law citations are still good there are some differences between the two. law, CiteCheck shows any negative history and CasemakerDigest is a daily summary of state and federal appellate cases searchable by practice area. A few months after access to both Fastcase and Casemaker was introduced, the State Bar of According to the State Bar of Texas website, the Texas Texas Bar Blog featured an article with a Texas Plan is available free to all Texas lawyers review of both services. Attorney Grant and the Premium Plan is available free to solo Scheiner prefers Fastcase because of its easy firms and firms of 10 lawyers or less. The Texas transition to smartphones and tablets with the Plan includes Supreme Court of Texas opinions Fastcase app, available on both Andriod and Ap- and courts of appeal opinions dating back to ple. The mobile sync feature allows the user to 1759, Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals opinions, share search results and research materials the United States Code annotated, Texas stat- across all devices at once. -

Fortieth Emergency Order Regarding the Covid-19 State of Disaster

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS ════════════════════ Misc. Docket No. 21-9079 ════════════════════ FORTIETH EMERGENCY ORDER REGARDING THE COVID-19 STATE OF DISASTER ════════════════════════════════════════════════════ ORDERED that: 1. Governor Abbott has declared a state of disaster in all 254 counties in the State of Texas in response to the imminent threat of the COVID-19 pandemic. This Order is issued pursuant to Section 22.0035(b) of the Texas Government Code. 2. The Thirty-Eighth Emergency Order (Misc. Dkt. No. 21-9060) is renewed as amended. 3. Subject only to constitutional limitations, all courts in Texas may in any case, civil or criminal, without a participant’s consent: a. except as provided in paragraph 4, modify or suspend any and all deadlines and procedures, whether prescribed by statute, rule, or order, for a stated period ending no later than October 1, 2021; b. except as this Order provides otherwise, allow or require anyone involved in any hearing, deposition, or other proceeding of any kind—including but not limited to a party, attorney, witness, court reporter, grand juror, or petit juror—to participate remotely, such as by teleconferencing, videoconferencing, or other means; c. consider as evidence sworn statements made out of court or sworn testimony given remotely, out of court, such as by teleconferencing, videoconferencing, or other means; d. conduct proceedings away from the court’s usual location with reasonable notice and access to the participants and the public; e. require every participant in a proceeding to alert the court if the participant has, or knows of another participant who has: (i) COVID-19 or a fever, chills, cough, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, fatigue, muscle or body aches, headache, sore throat, loss of taste or smell, congestion or runny nose, nausea or vomiting, or diarrhea; or (ii) recently been in close contact with a person who is confirmed to have COVID-19 or exhibiting the symptoms described above; f. -

SJI Newsletter May 2019 | Volume 29, No

SJI Newsletter May 2019 | Volume 29, No. 8 Civil Justice Initiative Pilot Project Releases Miami-Dade Evaluation In November 2016, the Circuit Civil Division of the Eleventh Judicial Circuit Court of Florida implemented the Civil Justice Initiative Pilot Project (CJIPP) to test the impact of Civil Case Management Teams (CCMTs) on civil case processing. CCMTs were envisioned as an essential component of civil justice reform in the report and recommendations of the CCJ Civil Justice Improvements Committee. With SJI support, the CJIPP created four CCMTs, each consisting of a judge, a case manager, a judicial assistant, and a bailiff. The CCMTs developed a standardized case management process to streamline administrative tasks, triage cases into appropriate case management pathways, and monitor case progress. The remaining 21 judges in the Circuit Civil Division continued to manage civil caseloads under traditional case processing practices and staffing assignments, providing a baseline for comparison. To assess the impact of CJIPP, the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) conducted an outcome evaluation that compared the outcomes of cases assigned to the CJIPP teams with those assigned to the non- CJIPP judges (baseline). The NCSC found that CJIPP cases closed at a significantly higher rate, and approximately five months earlier on average than baseline cases. Shortly after the initial launch of the pilot program, the CJIPP cases experienced a temporary increase in the number of court hearings and case management conferences as lawyers in the CJIPP cases requested modifications to case management orders, including continuances or extensions of time to complete litigation tasks; however, the frequency of these case events returned to normal levels within three months.