Thesis Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking the KTX Catching a Taxi Hopping on the Bus and More Inside

Getting bigger and better, now with more than 2000 copies printed every month Vol. III Issue VII the Ulsanwww.ulsanpear.biz PearJanuary 2007 Getting Around Taking the KTX Catching a Taxi Hopping on the Bus and more inside... Taehwa Rotary Check out our Website! lots of back-issues everything you ever needed to know about living in Ulsan Cover photo by Bennett Ho FREE A Guide to Living in Korea’s Industrial Capital 무료 2 THE ulsan Pear Dear Pear Readers, By the time you read this, another year will have started, hopefully with a great holiday season behind all of us. New Year's is a time for resolutions, setting new goals and dreaming big. Now is the time to think of all the things you'd like to experience during your time in Emergency Contact Numbers Korea, and make the most of the mostly dry, sunny winter weather. speak very slowly, and clearly. One thing we should all endeavour to do is see more of the country we are living in. This issue provides lots of information on how to get around Ulsan and Korea, so get out and explore! Do not panic, ask for English We’re also taking a look at the possible future of Ulsan. I hope you all enjoy the trip through the looking glass. Ambulance 구급(Gu-Guep) Happy New Years from all of us at the Ulsan Pear! 119 Fire 화재 (Hwa-Jay) Kevin Forman 112 Police 경찰 (Gyeong-Chal) Editor-in-Chief 1366 Women Emergency CAll 00799 International Operator ™ THE ULSAN PEAR ESTABLISHED 2004 1330 Tourist Information CREATOR: Joel Burslem H Ulsan Hospital Emergency 052-259-5000 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Kevin Forman EDITORIAL BOARD/ -

SCUNTHORPE and GRIMSBY NEWSLETTER Group No

SCUNTHORPE AND GRIMSBY NEWSLETTER Group No. 7080 Charity No. 106312 May 2020 Summer Issue 1 Contents Hello & Welcome 3 Ad Lad Advertising in our Newsletter Dates for the Diary 4 Newsletter Distribution Social Nights MDU Committee Meetings Observer Meetings Support Family & Friends to Become an Advanced Driver Just for Fun SAGAM Team Members 5 Group Composition Chairman’s Chatter 6 Treasurers Report 6 Annual Balance Sheet 7 Rich’s Experiences in Thailand 8 Songran – Welcoming in the Thai New Year 9 Congratulations 10 Discount information 11 Editor’s Choice - Caught My Eye 11 Kia History RAC Review of Kia Venga Review of Social Night 16 How to Keep Your Car Healthy 18 Tribute to Sir Stirling Moss 19 IAM RoadSmart ADSM Group Audit 20 We Got Mail 23 Local Group Subscriptions Spot the Difference Keep Your Details Up To Date And Finally….. 2 Hello, welcome to the Summer edition of your newsletter! Well…. we are in May already – hasn’t the time flown by? Like me, I bet everyone is looking forward to the Summer being here properly, with some really nice weather and not much rain so we can enjoy our gardens to the full. We’ve put up a small greenhouse, have built a vegetable plot and are looking forward to having our home-grown vegetables for dinner. We will be planting/have planted various vegetables and plan on having a really good selection of herbs as well, so we can cook fresh for every meal. Actually, I don’t do much cooking myself as my husband is a professional chef – I just do the washing up and believe it or not there’s only the two of us!! So, less of the chit chat and on with the business of our Quarterly IAM magazine. -

MINISTRY of ENVIRONMENT REPUBLIC of KOREA Government Complex Gwacheon, 88 Gwanmoonro, Gwacheon-Si, Gyeonggi-Do, 427-729, Republic of Korea Tel

MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT REPUBLIC OF KOREA Government Complex Gwacheon, 88 Gwanmoonro, Gwacheon-si, Gyeonggi-do, 427-729, Republic of Korea Tel. 82-2-2110-6549 Fax. 82-2-504-9206 http://eng.me.go.kr ECOREA Environmental Review 2011, Korea MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT REPUBLIC OF KOREA Ecorea is a compound of the prefix“ Eco,”which suggests an ecologically sound and comfortable environment, and the name of the nation,“ Korea.” Contents The Minister’s Message 4 1. Overview of Korea 6 2. The Status and Trend of Environmental Quality 8 2-1. Nature 10 2-2. Air 18 2-3. Water 21 2-4. Soil 24 2-5. Waste 25 2-6. Chemicals 27 3. Environmental Issues and Measures 28 3-1. Nature Conservation and Biodiversity 30 3-2. Climate Change 39 3-3. Air Quality Management 44 3-4. Water Environment Management 49 3-5. Waste Resources Management 54 3-6. Environmental Health & Chemicals Management 59 3-7. Green Growth 66 3-8. International Environmental Cooperation 71 4. Leading Environmental Policies (2010) 84 4-1. Green Card 86 4-2. Four Major Rivers Restoration Project 91 4-3. Green City Pilot Project in Gangneung 98 4-4. Eco-friendly Food Culture 103 5. Subsidiary & Affiliated Organizations 108 5-1. National Institute of Environmental Research 110 5-2. National Institute of Environmental 113 Human Resources Development 5-3. Korea Environment Corporation 117 5-4. Korea National Park Service 120 5-5. SUDOKWON Landfill Site Management Corporation 124 5-6. Korea Environmental Industry & Technology Institute 127 6. Main Events in 2010 130 7. -

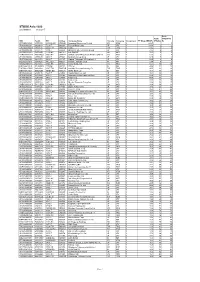

STOXX South Korea 200 Last Updated: 01.08.2017

STOXX South Korea 200 Last Updated: 01.08.2017 Rank Rank (PREVIOU ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) S) KR7005930003 6771720 005930.KS KR002D Samsung Electronics Co Ltd KR KRW Y 257.0 1 1 KR7000660001 6450267 000660.KS KR00EP SK HYNIX INC KR KRW Y 36.4 2 2 KR7005490008 6693233 005490.KS KR003E POSCO KR KRW Y 21.9 3 4 KR7035420009 6560393 035420.KS KR00NY NAVER CORP KR KRW Y 20.1 4 3 KR7055550008 6397502 055550.KS KR00AL Shinhan Financial Group Co Ltd KR KRW Y 19.1 5 7 KR7105560007 B3DF0Y6 105560.KS KR008J KB Financial Group Inc KR KRW Y 18.8 6 6 KR7005380001 6451055 005380.KS KR004F Hyundai Motor Co KR KRW Y 16.7 7 5 KR7012330007 6449544 012330.KS KR007I Hyundai Mobis KR KRW Y 12.8 8 8 KR7033780008 6175076 033780.KS KR00S3 KT&G Corp KR KRW Y 11.9 9 9 KR7051910008 6346913 051910.KS KR005G LG Chem Ltd KR KRW Y 11.7 10 11 KR7086790003 B0RNRF5 086790.KS KR06L2 Hana Financial G KR KRW Y 11.4 11 13 KR7015760002 6495730 015760.KS KR009K Korea Electric Power Corp KR KRW Y 10.6 12 15 KR7017670001 6224871 017670.KS KR048N SK TELECOM KR KRW Y 10.6 13 14 KR7028260008 BSXN8K7 028260.KS KR507N SAMSUNG C&T CORP KR KRW Y 10.5 14 10 KR7032830002 B12C0T9 032830.KS KR00BM Samsung Life Insurance Co Ltd KR KRW Y 10.3 15 16 KR7034730002 B39Z8L3 034730.KS KR053J SK HOLDINGS KR KRW Y 10.0 16 12 KR7000810002 6155250 000810.KS KR00JU Samsung Fire & Marine Insuranc KR KRW Y 8.9 17 17 KR7096770003 B232R05 096770.KS KR00HS SK INNOVATION KR KRW Y 8.2 18 22 KR7051900009 6344456 051900.KS KR05Q6 LG H&H KR KRW Y 7.7 -

STOXX Asia 1200 Last Updated: 02.01.2017

STOXX Asia 1200 Last Updated: 02.01.2017 Rank Rank (PREVIOU ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) S) KR7005930003 6771720 005930.KS KR002D Samsung Electronics Co Ltd KR KRW Y 199.0 1 1 JP3633400001 6900643 7203.T 690064 Toyota Motor Corp. JP JPY Y 157.8 2 2 TW0002330008 6889106 2330.TW TW001Q TSMC TW TWD Y 101.0 3 4 JP3902900004 6335171 8306.T 659668 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group JP JPY Y 82.9 4 5 HK0000069689 B4TX8S1 1299.HK HK1013 AIA GROUP HK HKD Y 64.5 5 6 CNE1000002H1 B0LMTQ3 0939.HK CN0010 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H CN HKD Y 62.6 6 7 JP3735400008 6641373 9432.T 664137 Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C JP JPY Y 56.6 7 10 HK0941009539 6073556 0941.HK 607355 China Mobile Ltd. CN HKD Y 56.1 8 8 JP3436100006 6770620 9984.T 677062 Softbank Group Corp. JP JPY Y 54.9 9 9 JP3890350006 6563024 8316.T 656302 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Grou JP JPY Y 51.3 10 12 JP3854600008 6435145 7267.T 643514 Honda Motor Co. Ltd. JP JPY Y 50.3 11 11 INE002A01018 6099626 RELI.BO IN0027 Reliance Industries Ltd IN INR Y 44.5 12 15 JP3496400007 6248990 9433.T 624899 KDDI Corp. JP JPY Y 43.7 13 13 JP3885780001 6591014 8411.T 625024 Mizuho Financial Group Inc. JP JPY Y 43.3 14 14 TW0002317005 6438564 2317.TW TW002R Hon Hai Precision Industry Co TW TWD Y 37.4 15 18 CNE1000003G1 B1G1QD8 1398.HK CN0021 ICBC H CN HKD Y 37.1 16 16 JP3726800000 6474535 2914.T 647453 Japan Tobacco Inc. -

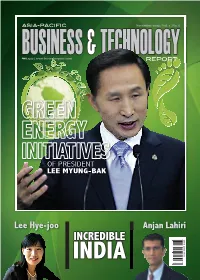

Lee Myung-Bak

ASIA-PACIFICBUSINESS & TECHNOLOGYNovember 2009 / Vol. 1, No. 6 W8,500 | www.biztechreport.com REPORT OF PRESIDENT LEE MYUNG-BAK Lee Hye-joo Anjan Lahiri INCREDIBLE ISSN 2092-7738 INDIA ASIA-PACIFICBUSINESS & TECHNOLOGY REPORT Contents November 2009 / Vol. 1, No. 6 | www.biztechreport.com COVER STORY 6 gReeN eNeRgy iNiTiATiVeS GREEN 32 Risk Factors 10 Pedal Power Consumer Tech industry Publisher: Lee Deuk Ho Editor-in-Chief: Lee Deuk Ho Seoul Promotes Bicycles Published by: Asia-Pacific Business & INNOVATION Technology Report Co. 34 Korean Websites Registration date: 2009.09.03 POLITICS Registration number: 서올중. 라00307 Lack of Foresight Price: W8,500/ US$8 12 Family Reunions Annual subscription fee: W96,000/ US$90 Reuniting Long-lost Relatives 36 MindTree Coping with global Recession Chief Consultant DR. LAkHViNDeR SiNgH IT 40 Emerging Opportunity Indo-Korean Business and Policy Forum Product Development and Resourcing Editorial Advisory Board 16 Web-Based Training N K Goyal President, Communications & Manufacturing 8 Reasons Against it Association of India, CMAI HUMAN DR. MezyAD ALTeRkAWi 20 Health IT Systems Associate Professor, King Saud University Long Road Ahead for Asia RESOURCES MR. eMANUeL yi PASTReiCH 42 Diversity Director, The Asia Institute 24 Cloud Computing MR. JUNgSoo JANg Workforce at Asian organizations President, Korea Future Institute A Number of Possibilities 28 Snovasoft To contact Asia Pacific Business and TRAVEL Technology Report for advertising, sub- missions, subscriptions or emerging giant in iT general comments -

Thesis Proposal

Analysis of the Present Curriculum: The Kingdom of God, and Proposal for the Future Curriculum of the Presbyterian Church of Korea by Hyeok-Su Chae A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Knox College and the Pastoral Department of the Toronto School of Theology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael’s College © Copyright by Hyeok-Su Chae 2014 Analysis of The Present Curriculum: The Kingdom of God, and Proposal for the Future Curriculum of the Presbyterian Church of Korea Hyeok-Su Chae Doctor of Philosophy University of St. Michael's College 2014 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to analyze the present curriculum of the Presbyterian Church of Korea (PCK), and to propose a new curriculum for the future. In 2001, facing the new millennium, the PCK published the current curriculum, “The Kingdom of God: Calling and Responding.” This curriculum was based on the theories of three scholars. It used broad concepts of curriculum developed by Yong-Soo Koh based on the educational theory of Maria Harris, Reformed Church theology by Myung-Yong Kim, and cultural insights by Sung-Hee Lee based on the Korean context. This thesis analyzes the curriculum from three perspectives: educational, theological, and cultural. It examines the congruence between these foundational theories and their application in the written curriculum. Several questions arise from educational, theological, and cultural perspectives. From an educational perspective, is the PCK curriculum true to the broad and holistic curriculum understanding of Maria Harris on which the curriculum was based? From a theological perspective, does this curriculum integrate the theological identity of the Reformed (Presbyterian) Church? From a cultural perspective, has this curriculum adequately considered the unique Korean cultural context? ii This thesis answers these questions by examining the PCK curriculum based on its foundational theories and the Korean context. -

STOXX South Korea 200 Last Updated: 01.03.2017

STOXX South Korea 200 Last Updated: 01.03.2017 Rank Rank (PREVIOU ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) S) KR7005930003 6771720 005930.KS KR002D Samsung Electronics Co Ltd KR KRW Y 225.0 1 1 KR7000660001 6450267 000660.KS KR00EP SK HYNIX INC KR KRW Y 22.6 2 2 KR7005380001 6451055 005380.KS KR004F Hyundai Motor Co KR KRW Y 20.3 3 4 KR7035420009 6560393 035420.KS KR00NY NAVER CORP KR KRW Y 19.8 4 3 KR7005490008 6693233 005490.KS KR003E POSCO KR KRW Y 17.6 5 6 KR7055550008 6397502 055550.KS KR00AL Shinhan Financial Group Co Ltd KR KRW Y 17.4 6 5 KR7105560007 B3DF0Y6 105560.KS KR008J KB Financial Group Inc KR KRW Y 16.3 7 7 KR7012330007 6449544 012330.KS KR007I Hyundai Mobis KR KRW Y 14.6 8 8 KR7000270009 6490928 000270.KS KR00GR Kia Motors Corp KR KRW Y 12.9 9 10 KR7028260008 BSXN8K7 028260.KS KR507N SAMSUNG C&T CORP KR KRW Y 12.2 10 9 KR7033780008 6175076 033780.KS KR00S3 KT&G Corp KR KRW Y 11.7 11 11 KR7017670001 6224871 017670.KS KR048N SK TELECOM KR KRW Y 11.6 12 12 KR7015760002 6495730 015760.KS KR009K Korea Electric Power Corp KR KRW Y 11.4 13 13 KR7051910008 6346913 051910.KS KR005G LG Chem Ltd KR KRW Y 10.4 14 15 KR7032830002 B12C0T9 032830.KS KR00BM Samsung Life Insurance Co Ltd KR KRW Y 9.6 15 14 KR7034730002 B39Z8L3 034730.KS KR053J SK HOLDINGS KR KRW Y 8.8 16 17 KR7086790003 B0RNRF5 086790.KS KR06L2 Hana Financial G KR KRW Y 8.7 17 18 KR7000810002 6155250 000810.KS KR00JU Samsung Fire & Marine Insuranc KR KRW Y 8.5 18 16 KR7096770003 B232R05 096770.KS KR00HS SK INNOVATION KR KRW -

STOXX Asia 1200 Last Updated: 01.06.2017

STOXX Asia 1200 Last Updated: 01.06.2017 Rank Rank (PREVIOU ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) S) KR7005930003 6771720 005930.KS KR002D Samsung Electronics Co Ltd KR KRW Y 249.7 1 1 JP3633400001 6900643 7203.T 690064 Toyota Motor Corp. JP JPY Y 131.8 2 2 TW0002330008 6889106 2330.TW TW001Q TSMC TW TWD Y 113.5 3 3 JP3902900004 6335171 8306.T 659668 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group JP JPY Y 78.7 4 4 HK0000069689 B4TX8S1 1299.HK HK1013 AIA GROUP HK HKD Y 76.0 5 5 CNE1000002H1 B0LMTQ3 0939.HK CN0010 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H CN HKD Y 63.0 6 7 JP3436100006 6770620 9984.T 677062 Softbank Group Corp. JP JPY Y 62.9 7 8 JP3735400008 6641373 9432.T 664137 Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C JP JPY Y 60.5 8 9 INE002A01018 6099626 RELI.BO IN0027 Reliance Industries Ltd IN INR Y 59.9 9 6 HK0941009539 6073556 0941.HK 607355 China Mobile Ltd. CN HKD Y 55.1 10 10 INE154A01025 B0JGGP5 ITC.BO IN007C ITC Ltd IN INR Y 49.4 11 13 TW0002317005 6438564 2317.TW TW002R Hon Hai Precision Industry Co TW TWD Y 46.0 12 14 INE040A01026 B5Q3JZ5 HDBK.BO IN00CH HDFC Bank Ltd IN INR Y 45.4 13 15 JP3854600008 6435145 7267.T 643514 Honda Motor Co. Ltd. JP JPY Y 45.4 14 11 JP3890350006 6563024 8316.T 656302 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Grou JP JPY Y 45.2 15 12 JP3496400007 6248990 9433.T 624899 KDDI Corp. -

Essays on Industrial Networking and Small and Medium Firms

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KDI School Archives - ESSAYS ON INDUSTRIAL NETWORKING AND SMALL AND MEDIUM FIRMS By Yeon-Sook Park DISSERTATION Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph. D. IN PUBLIC POLICY Spring 2006 ESSAYS ON INDUSTRIAL NETWORKING AND SMALL AND MEDIUM FIRMS By Yeon-Sook Park DISSERTATION Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph. D. IN PUBLIC POLICY Spring 2006 ESSAYS ON INDUSTRIAL NETWORKING AND SMALL AND MEDIUM FIRMS By Yeon-Sook Park DISSERTATION Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph. D. IN PUBLIC POLICY Committee in charge Professor Hun-Joo PARK, Chairperson Professor Tae-Jong KIM Professor Byung-Joon AHN Approved May 31, 2006 Spring 2006 2006 by Yeon-Sook Park All rights reserved. ABSTRACT ESSAYS ON INDUSTRIAL NETWORKING AND SMALL AND MEDIUM FIRMS By Yeon-Sook Park The three essays presented in this dissertation aim to investigate the relationship between industrial networking and the growth of small and medium firms in Korea. Chapter 1 Firm Size, Age, Industrial Networking, and Growth: A Case of Korean Manufacturing . The first essay investigates the relationships among firm size, age, industrial networking, and firm growth using the balanced panel data of 7,889 Korean manufacturing firms between 1994 and 2003. The result confirms Evans’ study in 1987 that firm size and age have significant negative effects on firm growth and significant positive impacts on firm survivability. -

Investigating the Korean Bicycle Industry at the Kintex Show

Exhibitions Kintex Show Investigating the Korean Bicycle Industry at the Kintex Show Text & Photos: Grace S. Ruan hanks to the Korean gov- Although 70% of all Korean bi- Ternment’s incentives to cycles are currently MTBs (pre- the cycle industry and its ac- viously as high as 80%), road tive construction of bike paths, bikes—despite their low popu- the cycling environment is very larity in Korea—have become a good and Korean cycle industry new favorite over the last four has been enjoying good pros- years and show signs of steady ▲Seoul has many bridges (the Han River flows beneath). pects over the past few years. growth. 94 BMU 2012 Spring www.biketaiwan.com Kintex Show Exhibitions and 1.3 million units in recent Korean President Lee Myung- decades, sales have surpassed 2 bak loves sports and cycling, million units during the past four and therefore wishes to create an years due to the government’s excellent cycling environment promotions of environmental encouraging the Korean people awareness and cycling, and the to ride bikes. South Koreans like large-scale constructions of bike to use the Internet and often em- paths (especially bike paths along ploy it to invite their friends go rivers). Additionally, anyone can out to ride bikes, so it’s unsur- ▲Full of locks and cards, the card tree signifies easily rent a bike in many parks. prising that the bicycle growth good fortune and love. The Nakdong River (525 rate is around 10% annually. The km) is South Korea’s longest riv- cycling population consists of There are 50 million people er and has 389 kilometers of bike two major groups—middle aged in South Korea and 23 million in paths along its banks.