Download (2410Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apocalypse and Survival

APOCALYPSE AND SURVIVAL FRANCESCO SANTINI JULY 1994 FOREWORD !e publication of the Opere complete [Complete Works] of Giorgio Cesa- rano, which commenced in the summer of 1993 with the publication of the "rst comprehensive edition of Critica dell’utopia capitale [Critique of the uto- pia of capital], is the fruit of the activity of a group of individuals who were directly inspired by the radical critique of which Cesarano was one of the pioneers. In 1983, a group of comrades who came from the “radical current” founded the Accademia dei Testardi [Academy of the Obstinate], which published, among other things, three issues of the journal, Maelström. !is core group, which still exists, drew up a balance sheet of its own revolution- ary experience (which has only been partially completed), thus elaborating a preliminary dra# of our activity, with the republication of the work of Gior- gio Cesarano in addition to the discussion stimulated by the interventions collected in this text.$ In this work we shall seek to situate Cesarano’s activity within its his- torical context, contributing to a critical delimitation of the collective envi- ronment of which he formed a part. We shall do this for the purpose of more e%ectively situating ourselves in the present by clarifying our relation with the revolutionary experience of the immediate past. !is is a necessary theoret- ical weapon for confronting the situation in which we "nd ourselves today, which requires the ability to resist and endure in totally hostile conditions, similar in some respects to those that revolutionaries had to face at the begin- ning of the seventies. -

Living on the Edge: Delineating the Political Economy of Precarity In

Living on the Edge: Delineating the Political Economy of Precarity in Vancouver, Canada Robert Catherall School of Community and Regional Planning, University of British Columbia ABSTRACT Canadian cities are in the midst of a housing crisis, with Vancouver as their poster-child. The city’s over- inflated housing prices decoupled from wages in the early aughts, giving rise to a seller’s rental market and destabilizing employment. As neoliberal policies continue to erode the post-war welfare state, an increasing number of Canadians are living in precarious environments. This uncertainty is not just applicable to housing, however. Employment tenure has been on the decline, specifically since 2008, and better jobs—both in security and quality of work, with more equitable wages—are becoming less and less common. These elements of precarity are making decent work (as defined by the ILO), security of housing tenure, and a right to the city some of the most pressing issues at hand for Canadians. Using Vancouver as the principal case study, the political economy of precarity is examined through the various facets—including socio-cultural, economic, health, and legal—that are working to normalize this inequity. This paper proceeds to examine the standard employment relationship (SER) in a Canadian context through a critique of the neoliberal policies responsible for eroding the once widely-implemented SER is provided to conclude the systemic marginalization experienced by those in precarious and informal situations must be addressed via public policy instruments and community-based organization. INTRODUCTION While the sharing economy, such as shared housing provider Airbnb, or the gig economy associated with organizations like Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, and Fiverr, conjure images of affordable options for travellers, or employment opportunities during an economic downturn, they have simultaneously normalized housing crises and stagnating wages for those who live and work in urban centres. -

The Struggles of Iregularly-Employed Workers in South Korea, 1999-20121

1 The Struggles of Iregularly-Employed Workers in South Korea, 1999-20121 Jennifer Jihye Chun Department of Sociology University of Toronto [email protected] November 25, 2013 In December 1999, two years after the South Korean government accepted a $58.4 billion bailout package from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), President Kim Dae-Jung announced that the nation’s currency crisis was officially over. The South Korean government’s aggressive measures to stabilize financial markets, which included drastic efforts to reduce labor costs, dismantle employment security, and legalize indirect forms of dispatch or temporary employment, contributed to the fastest recovery of a single country after the 1997 Asian Debt Crisis, restoring annual GDP growth rates to pre-crisis levels.2 While the business community praised such efforts for helping debt-ridden banks and companies survive the crisis, labor unions and other proponents of social and economic justice virulently condemned the government’s neoliberal policy agenda for subjecting workers to deepening inequality and injustice. Despite differing opinions on the impact of government austerity measures, both sides agree that the “post-IMF” era is synonymous with a new world of work. Employment precarity – that is, the vulnerability of workers to an array of cost-cutting employer practices that depress wage standards, working conditions and job and income security – is a defining feature of the 21st century South Korean economy. The majority of jobs in the labor market consist of informal and precarious jobs that provide minimal, if any, legal protection against unjust and discriminatory employment practices. Informally- and precariously- employed workers also face numerous barriers to challenging deteriorating working conditions and heightened employer abuses through the conventional repertoire of unionism: strikes, collective bargaining and union agreements. -

Where Did Braverman Go Wrong? a Marxist Response to the Politicist Critiques

Where did Braverman go wrong? A Marxist response to the politicist critiques Onde está errado Braverman? A resposta marxista às críticas politicistas Eduardo Sartelli1 Marina Kabat2 Abstract Braverman is considered an unquestionable reference of Marxist labour process. The objective of this paper is to show that despite Braverman’s undeniable achievements he forsakes the classical Marxist notions related to work organization, i. e. simple cooperation, manufacture and large-scale industry and replaces them with the notion of Taylorism. We also intend to show that because of this abandonment, Braverman cannot explain properly how the deskilling tendency operates in different historical periods, and in distinct industry branches. Finally, we try to demonstrate that those Marxist concepts neglected by Braverman are especially useful to understand labor unrest related to job organization. Braverman overvalues the incidence of labor fragmentation and direct forms of control and disregards the impact of mechanization achieved with the emergence of Large-scale industry and the new forms of control associated with it. Whereas Braverman’s allegedly Marxist orthodoxy is considered responsible for this, in fact, exactly the opposite can be asserted: the weaknesses of the otherwise noteworthy work of Harry Braverman are grounded in his relinquishment of some crucial Marxist concepts. We state that labor processes conventionally considered Taylorist or Fordist can be reconceptualized in Marxist classic terms allowing a better understanding of the dynamic of conflicts regarding labor process. Keywords: Labor process. Politics. Marxism. Regulationism. Workers’ Struggles. Resumo Braverman é considerado uma referência inquestionável do processo de trabalho marxista. O objetivo deste artigo é mostrar que, apesar das contribuições inegáveis de Braverman ele abandona as noções marxistas clássicas relacionadas à organização do trabalho, a saber, cooperação simples, manufatura e grande-indústria e substituí-las com a noção do taylorismo. -

The Hidden Work of Challenging Precarity

THE HIDDEN WORK OF CHALLENGING PRECARITY KIRAN MIRCHANDANI MARY JEAN HANDE Abstract. This article explores the hidden work of workers employed in pre- carious jobs which are characterized by part-time and temporary contracts, limited control over work schedules, and poor access to regulatory protection. Through 77 semi-structured interviews with workers in low-wage, precarious jobs in Ontario, Canada, we examine workers’ attempts to challenge the precar- ity they face when confronted by workplace conditions violating the Ontario Employment Standards Act (ESA), such as not being paid minimum wages, not being paid for overtime, being fired wrongfully or being subject to reprisals. We argue that these challenges involve hidden work, which is neither acknowledged nor recognized in the current ESA enforcement regime. We examine three types of hidden work that involve (1) creating a sense of positive self-worth amidst disempowering practices; (2) engaging in advocacy vis-à-vis employers, some- times through launching official claims with the Ontario Ministry of Labour; and (3) developing strategies to avoid the costs of job precarity in the future. We show that this hidden work of challenging job precarity needs to be formally recognized and that concrete strategies for doing so would lead to more robust protection for workers, particularly within ESA enforcement practices. Keywords: Hidden Work, Employment Relationships, Employment Standards, Low-wage work, Precarity, Stratification. Résumé. Cet article explore le travail caché de ceux qui occupent des emplois précaires se caractérisant par des contrats à temps partiel et temporaires, un con- trôle limité de leurs horaires de travail et des lacunes en matière de protection réglementaire. -

“Bifo” Berardi Marco Deseriis Theory & Event, Volume 1

Irony and the Politics of Composition in the Philosophy of Franco “Bifo” Berardi Marco Deseriis Theory & Event, Volume 15, Issue 4, 2012. Abstract By analyzing Franco Berardi’s reflections on irony as an extension of his political praxis, the article first examines the multifaceted functions of this rhetorical device in the contexts of the late-1960s social struggles against factory work in Italy, the communication experiments of the Autonomia movement, and the information overload of the contemporary mediascape. In the second part, the text addresses Berardi’s attempt to reconcile Jean Baudrillard’s theory of simulacra with Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s theory of desire to end with a reflection on how his distinction between irony and cynicism may offer a counterpoint to Slavoj Žižek’s critique of ideology. Keywords Irony; class composition; Italian workerism; social movements; subjectivity; autonomy. Born in Bologna in 1949, Franco “Bifo” Berardi has participated in four major anti-capitalist movements in the past four decades: the 1968 as a member of the Marxist revolutionary group Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power); the movement of Autonomia in 1977; the alter-globalization movement in the late 1990s-early 2000s; and the current European movement against austerity measures, the precarization of labor conditions, and the budget cuts to public education. Berardi has combined this personal engagement with an ongoing experimentation with social movement media such as the magazine A/Traverso, the experimental community radio Radio Alice, both founded in Bologna in the mid-1970s. In the late 1990s, he launched the e-mail list Rekombinant and, in the early 2000s, the community TV Orfeo TV. -

Precarity: a Savage Journey to the Heart of Embodied Capitalism

10 2006 Precarity: A Savage Journey to the Heart of Embodied Capitalism Vassilis Tsianos / Dimitris Papadopoulos A. Introduction There is an underlying assumption to the current debates about class composition in post-Fordism: this is the assumption that immaterial work and its corresponding social subjects form the centre of gravity in the new turbulent cycles of struggles around living labour. This paper explores the theoretical and political implications of this assumption, its promises and closures. Is immaterial labour the condition out of which a radical socio-political transformation of contemporary post-Fordist capitalism can emerge? Who’s afraid of immaterial workers today? B. Immaterial labour and precarity In their attempt to historicize the emergence of the concept of the general intellect, many theorists (e.g. Hardt & Negri, 2000; Virno, 2004) remind us that the general intellect cannot be conceived simply as a sociological category. We think that we should apply the same precaution when using the concept of immaterial labour. This is the case especially when the studies which acknowledge the sociological evidence of immaterial work are increasing, such as research in the mainstream sociology of work which investigates atypical employment and the subjectivisation of labour (e.g. Lohr & Nickel, 2005; Moldaschl & Voss, 2003), or even conceptualisations of immaterial labour in the context of knowledge society (e.g. Gorz, 2004). A mere sociological understanding of the figure of immaterial labour is restricted to a simplistic description of the spreading of features such as affective labour, networking, collaboration, knowledge economy etc. into what mainstream sociology calls network society (Castells, 1996). What differentiates a mere sociological description from an operative political conceptualisation of immaterial labour – which is situated in co-research and political activism (Negri, 2006) – is the quest for understanding the power dynamics of living labour in post-Fordist societies. -

For the Global Emancipation of Labour: New Movements and Struggles Around Work, Workers and Precarity

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Call for papers Volume 3 (2): 478 - 481 (November 2011) Vol 4 (2): global emancipation of labour Call for papers vol 4 issue 2 (November 2012) For the global emancipation of labour: new movements and struggles around work, workers and precarity Issue editors: Alice Mattoni, Elizabeth Humphrys, Peter Waterman, Ana Margarida Esteves Once, the labour movement was seen as the international social movement for the left (and it was the spectre haunting capitalism). Over the last century, however, labour movements have been transformed. In most of the world membership rates have dwindled, and many act in defence of, or simply provide services to, their members in the spirit of interest or lobbying groups. Labour was once a broad social movement including cooperatives, socialist parties, women’s and youth wings, press and publications, cultural production and sporting clubs. Often it was at the core of movements for democracy or national independence, even of social revolution. Despite the rhetoric of “socialism”, “class and mass trade unionism” or, alternatively, technocratic “organising strategies”, most union movements internationally operate strictly within the parameters of capitalism and the ideology of “social partnership” (i.e. with and under capital and state). New labour organising efforts are increasingly moving beyond traditional trade union forms, dependence on the state or parties of the left, and have found new forms linked to ethnic or geographical communities, working women, precarious workers, migrants and other radical-democratic social movements. These changes may relate to the neoliberalisation and “globalization” of capitalism, and its result in restructured industry and employment. -

Workerism and Politics

Historical Materialism 18 (2010) 186–189 brill.nl/hima Workerism and Politics Mario Tronti Centro per la Riforma dello Stato [email protected] Abstract !is is the text of Mario Tronti’s lecture at the 2006 Historical Materialism conference. It provides a brief, evocative synopsis of Tronti’s understanding of the historical experience and contemporary relevance of operaismo, a theoretical and practical attempt, embodied in journals such as Quaderni Rossi and Classe Operaia, to renew Marxist thought and politics in the Italy of the 1960s through a renewed attention to class-antagonism and the changing composition of labour. Keywords capitalism, communism, factory, Italy, labour-power, workerism First, what is ‘workerism’? It is an experience that tried to unite the thinking and practice of politics, in a determinate domain, that of the modern factory. It looked for a strong subject, the working class, capable of contesting and putting into crisis the mechanism of capitalist production. I underscore its character as an experience. Young intellectual forces were involved, encountering the new levies of workers, introduced especially into the large factories of the Taylorist and Fordist phase of capitalist industry. What had taken place in the thirties in the US was happening in the sixties in Italy. !e historical context for workerism was precisely that of the sixties of the twentieth century. In Italy, that period witnessed the take-off of an advanced capitalism, the passage from an agricultural-industrial society to an industrial- agricultural one, with the migratory displacement of labour-power from the peasant South to the industrial North. !ey called it ‘neo-capitalism’. -

Segmentation, Fragmentation and Transnational Migrant Labour In

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF EVERYDAY PRECARITY : SEGMENTATION , FRAGMENTATION AND TRANSNATIONAL MIGRANT LABOUR IN CALIFORNIAN AGRICULTURE A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 FABIOLA MIERES SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES /P OLITICS LIST OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................................... 7 DECLARATION ................................................................................................................................... 8 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ................................................................................................................... 9 DEDICATION ..................................................................................................................................... 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................... 10 THE AUTHOR ................................................................................................................................... 11 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................. 12 INTRODUCTION: LICENCE TO EXPLOIT? NEW INSIGHTS INTO MEXICAN MIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES ................................................................................................................................ 15 Background -

The Intersectionality of Precarity

104 Symposium and automation shape what kind of work a vital task, one that transcends the silos of gets seen as precarious? What kind of polit- sociology to expand our reckoning of impor- ical and cultural conditions affect the trajec- tant social trends: understanding the tory of technology and its impact on who broader impacts of provisioning. gets to have work, who must work, and whose precarious lives depend on it? By adding culture, race and gender inequal- References ities, and technology to the conversation, Collins, Caitlyn. 2019. Making Motherhood Work: we can use Precarious Lives to think further How Women Manage Careers and Caregiving. about a future that is already here. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Kalleberg has written a comprehensive Gordon, Linda. 1995. Pitied but Not Entitled: Single comparative analysis of precarious work Mothers and the History of Welfare, 1890–1935. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. and its effects that ripple out well beyond Pugh, Allison J. 2015. The Tumbleweed Society: work and the workplace. It is important Working and Caring in an Age of Insecurity. that we understand how countries have New York: Oxford University Press. managed these effects and how institutional Quadagno, Jill S. 1994. The Color of Welfare: How and cultural practices shape consequences Racism Undermined the War on Poverty. New for the well-being of people, their families, York: Oxford University Press. and communities. The book contributes to The Intersectionality of Precarity JOYA MISRA University of Massachusetts-Amherst [email protected] In Precarious Lives: Job Insecurity and Well- long experienced ‘‘uncertain, insecure, and Being in Rich Democracies, Arne Kalleberg risky work relations’’ (p. -

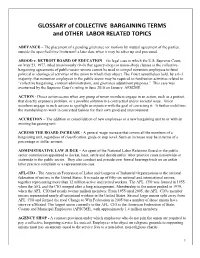

GLOSSARY of COLLECTIVE BARGAINING TERMS and OTHER LABOR RELATED TOPICS

GLOSSARY of COLLECTIVE BARGAINING TERMS and OTHER LABOR RELATED TOPICS ABEYANCE – The placement of a pending grievance (or motion) by mutual agreement of the parties, outside the specified time limits until a later date when it may be taken up and processed. ABOOD v. DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCATION – The legal case in which the U.S. Supreme Court, on May 23, 1977, ruled unanimously (9–0) that agency-shop (or union-shop) clauses in the collective- bargaining agreements of public-sector unions cannot be used to compel nonunion employees to fund political or ideological activities of the union to which they object. The Court nevertheless held, by a 6–3 majority, that nonunion employees in the public sector may be required to fund union activities related to “collective bargaining, contract administration, and grievance adjustment purposes.” This case was overturned by the Supreme Court’s ruling in June 2018 on Janus v. AFSCME. ACTION - Direct action occurs when any group of union members engage in an action, such as a protest, that directly exposes a problem, or a possible solution to a contractual and/or societal issue. Union members engage in such actions to spotlight an injustice with the goal of correcting it. It further mobilizes the membership to work in concerted fashion for their own good and improvement. ACCRETION – The addition or consolidation of new employees or a new bargaining unit to or with an existing bargaining unit. ACROSS THE BOARD INCREASE - A general wage increase that covers all the members of a bargaining unit, regardless of classification, grade or step level.