Education in England: Progress and Goals’, Centreforum, January 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France

KNOWLEDGE COMMUNITIES Lynch Education in Late Medieval France Elementary and Grammar Sarah B. Lynch Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France Lyon, 1285-1530 Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France Knowledge Communities This series focuses on innovative scholarship in the areas of intellectual history and the history of ideas, particularly as they relate to the communication of knowledge within and among diverse scholarly, literary, religious, and social communities across Western Europe. Interdisciplinary in nature, the series especially encourages new methodological outlooks that draw on the disciplines of philosophy, theology, musicology, anthropology, paleography, and codicology. Knowledge Communities addresses the myriad ways in which knowledge was expressed and inculcated, not only focusing upon scholarly texts from the period but also emphasizing the importance of emotions, ritual, performance, images, and gestures as modalities that communicate and acculturate ideas. The series publishes cutting-edge work that explores the nexus between ideas, communities and individuals in medieval and early modern Europe. Series Editor Clare Monagle, Macquarie University Editorial Board Mette Bruun, University of Copenhagen Babette Hellemans, University of Groningen Severin Kitanov, Salem State University Alex Novikoff, Fordham University Willemien Otten, University of Chicago Divinity School Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France Lyon, 1285-1530 Sarah B. Lynch Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Aristotle Teaching in Aristotle’s Politiques, Poitiers, 1480-90. Paris, BnF, ms fr 22500, f. 248 r. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 986 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 902 5 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789089649867 nur 684 © Sarah B. -

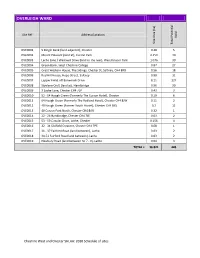

Schedule of Sites

OVERLEIGH WARD Site Ref Address/Location Yield Yield Site Area (ha) Total Potential Total OVE0001 5 Dingle Bank (land adjacent), Chester 0.48 5 OVE0002 Mount Pleasant (land at), Curzon Park 2.159 40 OVE0003 Lache Lane / Winkwell Drive (land to the rear), Westminster Park 1.076 30 OVE0004 Green Bank, West Cheshire College 0.87 27 OVE0005 Great Western House, The Sidings, Chester St, Saltney, CH4 8RD 0.56 18 OVE0006 Red Hill House, Hope Street, Saltney 0.99 31 OVE0007 Lapper Field, off Barwoods Drive 8.11 227 OVE0008 Styelane Croft (land at), Handbridge 0.96 30 OVE0009 3 Lache Lane, Chester CH4 7LP 0.43 3 OVE0010 52 - 54 Hough Green (Formerly The Curzon Hotel), Chester 0.19 6 OVE0011 64 Hough Green (Formerly The Redland Hotel), Chester CH4 8JW 0.11 2 OVE0012 40 Hough Green (Former Youth Hostel), Chester CH4 8JQ 0.2 11 OVE0013 40 Curzon Park North, Chester CH4 8AR 0.32 1 OVE0014 22 - 26 Handbridge, Chester CH4 7JE 0.03 2 OVE0015 53 - 59 Circular Drive, Lache, Chester 0.156 4 OVE0016 32 - 34 Oldfield Crescent, Chester CH4 7PE 0.08 1 OVE0017 31 - 37 Fairford Road (land between), Lache 0.03 2 OVE0018 34-51 Fairford Road land between), Lache 0.03 2 OVE0019 Newbury Road (land between no 7 - 9), Lache 0.04 3 TOTAL = 16.821 445 Cheshire West and Chester SHLAA: 2010 Schedule of sites Site Details Site Ref: OVE0001 Address/ 5 Dingle Bank (land adjacent), Chester Planning Status None/Other Location Site Area (Ha) 0.48 Ward Overleigh Source: Historic SHLAA Potential Yield 5 Ownership Density (per Ha) 35 Site Summary Key Site Characteristics Site Type Greenfield Garden adjacent to detached dwelling. -

Case Study of the English Early Childhood Education and Care System

e Early h l Case Studies na of E A atio ar Trn ly d te Ch In il dh v o o d a E d u n c a t io t n a a n d g C a r e e S y s t e m s EvolvingResponsive a HarmonizedIntegrated Policymaking and Hybrid andUniversal Implementation:System of ECEC: Maintaining the Reform Momentum RespectingEarlyAFrom Careful Childhood Equality Children Balancing to Services:and Equity ActFamilies Using Data for Improvement HongSingaporeAustraliaEnglandFinland Kong Integrated and Universal Early Childhood Services: Using Data for Improvement A Case Study of the English Early Childhood Education and Care System Professor Kathy Sylva, Grace Murkett, and Beatriz Melendro October 5, 2018 CopyrightÓ 2018 Teachers College All rights reserved International Case Studies of Innovative Early Childhood Systems: England Contents Executive Summary 1 Part 1 Introduction 11 Chapter 1: Study Overview .......................................................................................................... 12 Rationale and Goals ................................................................................................................... 12 Study Architecture ..................................................................................................................... 14 Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 20 Data Collection, Analysis, and Validation................................................................................ 24 Definitions and Abbreviations -

Female Education in the Late Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries in England and Wales: a Study of Attitudes and Practi Ce

FEMALE EDUCATION IN THE LATE SIXTEENTH AND EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES IN ENGLAND AND WALES: A STUDY OF ATTITUDES AND PRACTI CE Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy: January 1996 Caroline Mary Kynaston Bowden Institute of Education, University of London \ 2 ABSTRACT OF THESIS This thesis provides a study of attitudes and practice in respect of female education in England and Wales in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. It begins with a review of primary and secondary sources, and throughout draws substantially upon personal documents consulted in collections of family papers covering a wide geographical area. These documents, it is argued are broadly representative of gentry families. Chapter Two examines the education of daughters; Chapter Three the role of women in marriage; Chapter Four motherhood. Each of these chapters examines the links between education and the roles girls and women fulfilled. Throughout these three chapters, contrasts and comparisons are drawn between prescriptive advice and practice. Chapter Five considers the difficult issue of standards in the education of girls and women, while the final chapter examines some of the outcomes of education in terms of women as intermediaries in informal power networks, estate and farm managers and educational benefactors and founders. The thesis draws conclusions in respect of the importance of education in permitting the developing role of women in both private and public spheres and examines the reasons for such changes. It also challenges existing theories regarding the differences between Catholic and Protestant attitudes to girls' education. A substantial appendix listing some 870 educated and literate women of the period is provided, both to demonstrate the major sources for this study and to provide a basis for future research. -

Year Review Elcome to This Festive Edition of Alert

December 2009 Keeping Cheshire Fire and Rescue Service Personnel Informed Year Review elcome to this festive edition of Alert. July saw crews dealing with a The past year has been one of major major explosion at flats in Hoole Wchange for the organisation, yet we have Lane, Chester – miraculously there still managed to deliver an excellent service to were no injuries. The month was local communities and hit our key targets. A also a time for departures, with fire sincere thank you to all staff and volunteers for cadets making their third successful your hard work and commitment - Happy school-building visit to Ghana and Kathryn Christmas and a peaceful New Year. Foreman, Deputy Chief Fire Officer for Paul Hancock, Chief Fire Officer Corporate Services saying farewell. David Topping, Chair of the Fire Authority August saw the Service taking pride The year started with the Service highlighted as of place with its pink fire appliance at one of the most progressive in the country in a Manchester’s massive Pride Parade. national report called ‘Rising to the Challenge: The stars were out in September at improving fire service efficiency’. the Service’s inaugural STAR awards February saw the launch of a new stores service event which ensured many of the from HQ following a major £30,000 refit. organisation’s ‘stars’ were recognised. Improvements included better computer access, There was another first with the launch of improved storage and stock management. the Co-Responder scheme at Nantwich. March saw celebrations as the Service hit its October was another time for target of carrying out 60,000 HSAs. -

Education System in the Uk

EDUCATION SYSTEM IN THE UK Across the UK there are five stages of education: early years, primary, secondary, Further Education (FE) and Higher Education (HE). Education is compulsory for all children between the ages of 5 (4 in Northern Ireland) and 16. FE is not compulsory and covers non-advanced education which can be taken at further (including tertiary) education colleges and HE institutions (HEIs). The fifth stage, HE, is study beyond GCE A levels and their equivalent which, for most full-time students, takes place in universities and other HEIs and colleges. Early Years Education In England since September 2010, all three and four year olds are entitled to 15 hours of free nursery education for 38 weeks of the year. Early Years education takes place in a variety of settings including state nursery schools, nursery classes and reception classes within primary schools, as well as settings outside the state sector such as voluntary pre-schools, privately run nurseries or childminders. In recent years there has been a major expansion of Early Years education and childcare. The Foundation Stage which was first introduced in September 2000, and covered children’s education from the age of 3 to the end of the reception year, when children are aged 5. The Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) came into force in September 2008, and is a single regulatory and quality framework for the provision of learning, development and care for children in all registered early years settings between birth and the academic year in which they turn 5. The EYFS Profile (EYFSP) is the statutory assessment of each child’s development and learning achievements at the end of the academic year in which they turn 5. -

Higher Education Funding Reforms: a Comprehensive Analysis of Educational and Labor Market Outcomes in England

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11083 Higher Education Funding Reforms: A Comprehensive Analysis of Educational and Labor Market Outcomes in England Ghazala Azmat Stefania Simion OCTOBER 2017 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11083 Higher Education Funding Reforms: A Comprehensive Analysis of Educational and Labor Market Outcomes in England Ghazala Azmat Sciences Po, CEP (LSE) and IZA Stefania Simion University of Edinburgh and CEP (LSE) OCTOBER 2017 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 11083 OCTOBER 2017 ABSTRACT Higher Education Funding Reforms: A Comprehensive Analysis of Educational and Labor Market Outcomes in England This paper investigates the impact of changes in the funding of higher education in England on students’ choices and outcomes. -

WP News Westminster Park Residents’ Association

December 2019 WP News Westminster Park Residents’ Association Sunset over Bringing our community alive Westminster Park www.wp-ra.org.uk @wesparkra Residents show care for our community obstruction, please think of others and trim it https://westcheshireyourstreets.co.uk/ back. Some residents may find this physically Fly-tipping has been noted by the bottle challenging, and people at the meeting banks on the shop car park – if you witness it, suggested that we could all be good please report it. neighbours and offer to help others. Speeding and inconsiderate parking, The idea of turning some of the larger particularly near the school, were also hot grassed areas on Westminster Park into topics at our meeting. Nobody wants to see wildflower meadows was very popular and we children involved in an accident, so please are hoping to work with the Council to bring ensure that you park with care around the this about over the next couple of years. school/shops area. PCSO Lauren Davies has The Council has started a new ‘Love Your recently visited the school to highlight this Caring for and enhancing our area, one of issue. There were calls for a zebra crossing the main objectives of your residents’ or lollipop person and Councillor Neil Sullivan association, was discussed at our recent agreed to pursue these suggestions with public meeting. Much is already happening – Council officers. last month we planted more bulbs for a great If you have any other ideas about how we spring display. Crocuses have gone in by the can improve our local area, please email me shops and daffodils around the junctions of at [email protected] or ring 07752 854383. -

The Right to Education in England

The Right to Education in England Alternative Report to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights September 2008 CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………………………………………………….2 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………...................3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………..11 Availability of education…………………………………………………………………………..13 No right to education for children held in custody………………………13 Children in immigration detention………………………………………...17 Lack of provision for children with special educational needs and disabilities…………………………………………………………………...19 Alternative provision for children not in school………………………….21 Access to education……………………………………………………………..26 Discrimination in access to education and educational outcomes for particular groups of children………………………………………….26 High rates of exclusion……………………………………………………37 Wide-spread bullying in schools…………………………………………40 Acceptability of education………………………………………………………44 Lack of participation of children in education…………………………...44 Content of education………………………………………………………47 Adaptability of education……………………………………………………….50 Inclusion: children with SEN in mainstream schools………………….50 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………52 FOREWORD This report was prepared by the Children’s Legal Centre – an independent national charity aimed at promoting children’s rights in the UK and worldwide. The Children’s Legal Centre has particular expertise in the area of education law, being one of the leading providers of education law advice and casework in England. Owing to the Centre’s particular expertise -

SCHOOL SYSTEM in the UK England Education in England May Differ from the System Used Elsewhere in the United Kingdom . Basicall

SCHOOL SYSTEM IN THE UK England Education in England may differ from the system used elsewhere in the United Kingdom . Basically, there are two systems: one covering England, Wales and Northern Ireland and one covering Scotland. The two education systems have different emphases. Traditionally the English, Welsh and Northern Irish system has emphasised depth of education whereas the Scottish system has emphasised breadth. Thus English, Welsh and Northern Irish students tend to sit a small number of more advanced examinations and Scottish students tend to sit a larger number of less advanced examinations. It should be noted that local English practice can vary from this general picture although Scottish practice is well nigh universal. Education in Wales Nowadays education in Wales differs slightly from the system used in England. The statutory national key stage tests in Wales were, until 2000, the same as in England and were managed by the School Curriculum and Assessment Authority (SCAA). In 2000, the National Assembly for Wales took responsibility for these tests in Wales, at which point they were developed by test agencies on behalf of the Awdurdod Cymwysterau, Cwricwlwm ac Asesu Cymru (ACCAC), whilst the tests in England were developed for the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA). In 2002, the Welsh Assembly decided to cease the tests at Key Stage One. Instead, optional teacher assessment materials were provided to schools in 2003 for use in English, mathematics and Welsh . These had been adapted from materials that had originally been developed by the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) and the other test agencies to be used as statutory assessment materials for 2003. -

Boys' Underachievement in Education

MEASUREMENT AND RESEARCH SUPPORT TO EDUCATION STRATEGY GOAL 1 BOYS’ UNDERACHIEVEMENT IN EDUCATION: A REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE WITH A FOCUS ON READING IN THE EARLY YEARS AUGUST 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by RTI International. MEASUREMENT AND RESEARCH SUPPORT TO EDUCATION STRATEGY GOAL 1 BOYS’ UNDERACHIEVEMENT IN EDUCATION: A REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE WITH A FOCUS ON READING IN THE EARLY YEARS Education Data for Decision Making (EdData II) Task Order No. AID-OAA-BC-12-00003 RTI Task Order 20, Activity 13 (Project No. 0209354.020.013) Prepared for Office of Education Bureau for Economic Growth, Education, and Environment (E3) United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Arthur Muchajer, Contracting Officer Penelope Bender, Contracting Officer’s Representative Prepared by Jyotsna Jha, RTI consultant; and Sarah Pouezevara RTI International 3040 East Cornwallis Road P.O. Box 12194 Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-2194 USA DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Cover photo: Schoolroom in Philippines (Sarah Pouezevara) Table of Contents List of Figures ...................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... -

Read the Full Report Here

1 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the LSE Housing and Communities Research Team in the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) at the London School of Economics (LSE), LSE. Thanks to Ceris Anderson and Jane Ashworth from StreetGames for their advice, support and information; also many local stakeholders who provided us with background information and introduced us to their areas – in particular Alex Tate, Sean Daley, Dale Gilmartin, Liz Holding, Geraldine Maddison, Matthew Jacklin, Delroy Hibbert, Andrew Birtwhistle, Harry Jenkinson, Daniel Burford and Jason Turner. We owe special thanks to the 106 young people and parents who shared their experiences. We accept full responsibility for any mistakes, misleading or incomplete information. About LSE Housing and Communities LSE Housing and Communities is a research unit within the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) at the London School of Economics led by Professor Anne Power. CASE is a multi-disciplinary research centre which focuses on the exploration of different dimensions of social disadvantage, particularly from longitudinal and neighbourhood perspectives, examining the impact of public policy. We aim to understand the social dynamics of disadvantaged neighbourhoods; promote models of housing and neighbourhood management; develop ways to support community and resident self-help action, especially in social housing areas; and shape government policy. 2 Contents Acknowledgements ...........................................................................................................................