Tony Blair Institute, Times Education Commission Submission, June

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France

KNOWLEDGE COMMUNITIES Lynch Education in Late Medieval France Elementary and Grammar Sarah B. Lynch Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France Lyon, 1285-1530 Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France Knowledge Communities This series focuses on innovative scholarship in the areas of intellectual history and the history of ideas, particularly as they relate to the communication of knowledge within and among diverse scholarly, literary, religious, and social communities across Western Europe. Interdisciplinary in nature, the series especially encourages new methodological outlooks that draw on the disciplines of philosophy, theology, musicology, anthropology, paleography, and codicology. Knowledge Communities addresses the myriad ways in which knowledge was expressed and inculcated, not only focusing upon scholarly texts from the period but also emphasizing the importance of emotions, ritual, performance, images, and gestures as modalities that communicate and acculturate ideas. The series publishes cutting-edge work that explores the nexus between ideas, communities and individuals in medieval and early modern Europe. Series Editor Clare Monagle, Macquarie University Editorial Board Mette Bruun, University of Copenhagen Babette Hellemans, University of Groningen Severin Kitanov, Salem State University Alex Novikoff, Fordham University Willemien Otten, University of Chicago Divinity School Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France Lyon, 1285-1530 Sarah B. Lynch Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Aristotle Teaching in Aristotle’s Politiques, Poitiers, 1480-90. Paris, BnF, ms fr 22500, f. 248 r. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 986 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 902 5 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789089649867 nur 684 © Sarah B. -

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

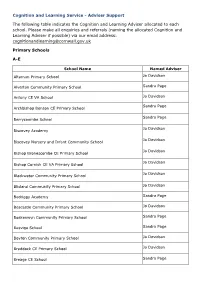

Cognition and Learning Schools List

Cognition and Learning Service - Adviser Support The following table indicates the Cognition and Learning Adviser allocated to each school. Please make all enquiries and referrals (naming the allocated Cognition and Learning Adviser if possible) via our email address: [email protected] Primary Schools A-E School Name Named Adviser Jo Davidson Altarnun Primary School Sandra Page Alverton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Antony CE VA School Sandra Page Archbishop Benson CE Primary School Sandra Page Berrycoombe School Jo Davidson Biscovey Academy Jo Davidson Biscovey Nursery and Infant Community School Jo Davidson Bishop Bronescombe CE Primary School Jo Davidson Bishop Cornish CE VA Primary School Jo Davidson Blackwater Community Primary School Jo Davidson Blisland Community Primary School Sandra Page Bodriggy Academy Jo Davidson Boscastle Community Primary School Sandra Page Boskenwyn Community Primary School Sandra Page Bosvigo School Boyton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Jo Davidson Braddock CE Primary School Sandra Page Breage CE School School Name Named Adviser Jo Davidson Brunel Primary and Nursery Academy Jo Davidson Bude Infant School Jo Davidson Bude Junior School Jo Davidson Bugle School Jo Davidson Burraton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Callington Primary School Jo Davidson Calstock Community Primary School Jo Davidson Camelford Primary School Jo Davidson Carbeile Junior School Jo Davidson Carclaze Community Primary School Sandra Page Cardinham School Sandra Page Chacewater Community Primary -

Case Study of the English Early Childhood Education and Care System

e Early h l Case Studies na of E A atio ar Trn ly d te Ch In il dh v o o d a E d u n c a t io t n a a n d g C a r e e S y s t e m s EvolvingResponsive a HarmonizedIntegrated Policymaking and Hybrid andUniversal Implementation:System of ECEC: Maintaining the Reform Momentum RespectingEarlyAFrom Careful Childhood Equality Children Balancing to Services:and Equity ActFamilies Using Data for Improvement HongSingaporeAustraliaEnglandFinland Kong Integrated and Universal Early Childhood Services: Using Data for Improvement A Case Study of the English Early Childhood Education and Care System Professor Kathy Sylva, Grace Murkett, and Beatriz Melendro October 5, 2018 CopyrightÓ 2018 Teachers College All rights reserved International Case Studies of Innovative Early Childhood Systems: England Contents Executive Summary 1 Part 1 Introduction 11 Chapter 1: Study Overview .......................................................................................................... 12 Rationale and Goals ................................................................................................................... 12 Study Architecture ..................................................................................................................... 14 Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 20 Data Collection, Analysis, and Validation................................................................................ 24 Definitions and Abbreviations -

Female Education in the Late Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries in England and Wales: a Study of Attitudes and Practi Ce

FEMALE EDUCATION IN THE LATE SIXTEENTH AND EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES IN ENGLAND AND WALES: A STUDY OF ATTITUDES AND PRACTI CE Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy: January 1996 Caroline Mary Kynaston Bowden Institute of Education, University of London \ 2 ABSTRACT OF THESIS This thesis provides a study of attitudes and practice in respect of female education in England and Wales in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. It begins with a review of primary and secondary sources, and throughout draws substantially upon personal documents consulted in collections of family papers covering a wide geographical area. These documents, it is argued are broadly representative of gentry families. Chapter Two examines the education of daughters; Chapter Three the role of women in marriage; Chapter Four motherhood. Each of these chapters examines the links between education and the roles girls and women fulfilled. Throughout these three chapters, contrasts and comparisons are drawn between prescriptive advice and practice. Chapter Five considers the difficult issue of standards in the education of girls and women, while the final chapter examines some of the outcomes of education in terms of women as intermediaries in informal power networks, estate and farm managers and educational benefactors and founders. The thesis draws conclusions in respect of the importance of education in permitting the developing role of women in both private and public spheres and examines the reasons for such changes. It also challenges existing theories regarding the differences between Catholic and Protestant attitudes to girls' education. A substantial appendix listing some 870 educated and literate women of the period is provided, both to demonstrate the major sources for this study and to provide a basis for future research. -

Education System in the Uk

EDUCATION SYSTEM IN THE UK Across the UK there are five stages of education: early years, primary, secondary, Further Education (FE) and Higher Education (HE). Education is compulsory for all children between the ages of 5 (4 in Northern Ireland) and 16. FE is not compulsory and covers non-advanced education which can be taken at further (including tertiary) education colleges and HE institutions (HEIs). The fifth stage, HE, is study beyond GCE A levels and their equivalent which, for most full-time students, takes place in universities and other HEIs and colleges. Early Years Education In England since September 2010, all three and four year olds are entitled to 15 hours of free nursery education for 38 weeks of the year. Early Years education takes place in a variety of settings including state nursery schools, nursery classes and reception classes within primary schools, as well as settings outside the state sector such as voluntary pre-schools, privately run nurseries or childminders. In recent years there has been a major expansion of Early Years education and childcare. The Foundation Stage which was first introduced in September 2000, and covered children’s education from the age of 3 to the end of the reception year, when children are aged 5. The Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) came into force in September 2008, and is a single regulatory and quality framework for the provision of learning, development and care for children in all registered early years settings between birth and the academic year in which they turn 5. The EYFS Profile (EYFSP) is the statutory assessment of each child’s development and learning achievements at the end of the academic year in which they turn 5. -

School Name Town County Post Code Head Teacher

Secondary POPPI Schools in partnership with Plymouth University 2015-16. Plymouth School name Town County Post Code Head teacher All Saints Church of England Academy Plymouth Plymouth Devon PL5 3NE Mr Peter Grainger Coombe Dean School Plymouth Devon PL9 8ES Mr S Lewis Devonport High School for Boys Plymouth Devon PL1 5QP Mr Kieran Earley Devonport High School for Girls Plymouth Devon PL2 3DL Mrs Anita Hemsi Eggbuckland Community College Plymouth Devon PL6 5YB Katrina Borowski Hele's School Plymouth Devon PL7 4LT Mr A Birkett Lipson Cooperative Academy Plymouth Devon PL4 7PG Mr Steve Baker Marine Academy Plymouth (MAP) Plymouth Devon PL5 2AF Mrs Helen Mathieson Notre Dame RC School Plymouth Devon PL6 5HN Ms Fiona Hutchings Ridgeway School Plymouth Devon PL7 2RS Mr John Didymus St Boniface's Catholic College Plymouth Devon PL5 3AG Mr Peter Eccles Stoke Damerel Community College Plymouth Devon PL3 4BD Ms Carol Hannaford Tor Bridge High Plymouth Devon PL6 8UN Mr Graham Browne UTC Plymouth Plymouth Devon PL1 4RL Ms Mary Cox Cornwall School name Town County Post Code Head teacher Bodmin College Bodmin Cornwall PL31 1DD Mr Brett Elliott Callington Community College Callington Cornwall PL17 7DR Mr Gary Lobbett Cape Cornwall School Penzance Cornwall TR19 7JX Mr Julie Nash Falmouth School Falmouth Cornwall TR11 4LH Mrs Sandra Critchley Fowey Community School Fowey Cornwall PL23 1HE Mr John Perry Hayle Community School Hayle Cornwall TR27 4DN Mrs Chris Jackman Humphry Davy School Penzance Cornwall TR18 2TG Mr Bill Marshall Launceston College Launceston -

Higher Education Funding Reforms: a Comprehensive Analysis of Educational and Labor Market Outcomes in England

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11083 Higher Education Funding Reforms: A Comprehensive Analysis of Educational and Labor Market Outcomes in England Ghazala Azmat Stefania Simion OCTOBER 2017 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11083 Higher Education Funding Reforms: A Comprehensive Analysis of Educational and Labor Market Outcomes in England Ghazala Azmat Sciences Po, CEP (LSE) and IZA Stefania Simion University of Edinburgh and CEP (LSE) OCTOBER 2017 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 11083 OCTOBER 2017 ABSTRACT Higher Education Funding Reforms: A Comprehensive Analysis of Educational and Labor Market Outcomes in England This paper investigates the impact of changes in the funding of higher education in England on students’ choices and outcomes. -

Allocation of Schools Per Case Work Officer

Information Classification: PUBLIC Statutory Special Educational Needs | Find Your Case Work Officer This list details the schools and postcodes that each case work officer is responsible for. West Cornwall Rupert Lawler: Area Casework Officer (West) email: [email protected] CWO: Bridget Bingley email: [email protected] Area Postcodes TR17, TR18, TR20 Early years Allocated by home address Independent special school (ISP) / out of Allocated by home address county Post 16 Allocated by home address Special school Curnow (Upper Y7 – 11) Allocated by home address, or if dual registered ACE Academy allocated by mainstream school base EHE Allocated by home address Allocated by home address if single registered and by APAs mainstream school base if dual registered Secondary schools Primary schools Humphry Davy Alverton, Germoe, Gulval, Heamoor, Ludgvan, Marazion, Mousehole, Newlyn, Pensans, St Hilary, St Mounts Bay Academy Maddern’s, St Mary’s CE, St Mary’s RC, Trythall CWO: Jenni Trewhella email: [email protected] Area Postcodes TR12, TR13 Early years Allocated by home address Independent special school (ISP) / out of Allocated by home address county Post 16 Allocated by home address Information Classification: PUBLIC Special school Curnow (Lower Y-1 – 6 & Post 16 Y12-14) Allocated by home address or if dual registered ACE Academy allocated by mainstream school base EHE Allocated by home address Allocated by home address if single registered and by APAs mainstream school base if dual registered Secondary -

The Right to Education in England

The Right to Education in England Alternative Report to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights September 2008 CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………………………………………………….2 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………...................3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………..11 Availability of education…………………………………………………………………………..13 No right to education for children held in custody………………………13 Children in immigration detention………………………………………...17 Lack of provision for children with special educational needs and disabilities…………………………………………………………………...19 Alternative provision for children not in school………………………….21 Access to education……………………………………………………………..26 Discrimination in access to education and educational outcomes for particular groups of children………………………………………….26 High rates of exclusion……………………………………………………37 Wide-spread bullying in schools…………………………………………40 Acceptability of education………………………………………………………44 Lack of participation of children in education…………………………...44 Content of education………………………………………………………47 Adaptability of education……………………………………………………….50 Inclusion: children with SEN in mainstream schools………………….50 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………52 FOREWORD This report was prepared by the Children’s Legal Centre – an independent national charity aimed at promoting children’s rights in the UK and worldwide. The Children’s Legal Centre has particular expertise in the area of education law, being one of the leading providers of education law advice and casework in England. Owing to the Centre’s particular expertise -

1 Recapturing Labour's Traditions? History, Nostalgia and the Re-Writing

Recapturing Labour’s Traditions? History, nostalgia and the re-writing of Clause IV Dr Emily Robinson University of Nottingham The making of New Labour has received a great deal of critical attention, much of which has inevitably focused on the way in which it placed itself in relation to past and future, its inheritances and its iconoclasm.1 Nick Randall is right to note that students of New Labour have been particularly interested in ‘questions of temporality’ because ‘New Labour so boldly advanced a claim to disrupt historical continuity’.2 But it is not only academics who have contributed to this analysis. Many of the key figures associated with New Labour have also had their say. The New Labour project was not just about ‘making history’ in terms of its practical actions; the writing up of that history seems to have been just as important. As early as 1995 Peter Mandelson and Roger Liddle were preparing a key text designed ‘to enable everyone to understand better why Labour changed and what it has changed into’.3 This was followed in 1999 by Phillip Gould’s analysis of The Unfinished Revolution: How the Modernisers Saved the Labour Party, which motivated Dianne Hayter to begin a PhD in order to counteract the emerging consensus that the modernisation process began with the appointment of Gould and Mandelson in 1983. The result of this study was published in 2005 under the title Fightback! Labour’s Traditional Right in the 1970s and 1980s and made the case for a much longer process of modernisation, strongly tied to the trade unions. -

Dr. Robin T. Pettitt Is Senior Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Kingston University - London

Dr. Robin T. Pettitt is Senior Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Kingston University - London. His main area of research is the internal life of political parties. 1 The ‘How’ of Election Manifestos in the British Labour Party: A source of ongoing controversy Introduction The organisational history of the British Labour Party is to a significant degree the story of an ongoing struggle over the ‘how’ of election manifestos, a struggle, somewhat ironically, partly driven by a broad based agreement over the ‘why’ of manifestos. British political parties and indeed British politics more widely, are programmatic – that is, based on the idea that election manifestos are a party’s plan for government. What is says in the manifesto is what the party will do in government, and anything less, or indeed more, becomes a source of criticism of that government. Because the manifesto is seen as a programme for government action, this also means that the answer to the ‘how’ takes on huge importance, because controlling the ‘how’ means controlling government action. In the Labour Party the answer to the ‘how’ question has been the source of a longstanding and often heated dispute. On the one hand there are those who believe that the party’s parliamentary leadership must control the ‘how’. The parliamentary party is responsible to the electorate and has to answer for their actions at election time. They should therefore have the main say in the policies they will have to defend at a general election. On the other hand, the parliamentary party is only there because of the work of the grassroots, who selected them as candidates, campaigned for them on the doorstep, and therefore have a right to influence what they do.