Physiological Dead Space and Alveolar Ventilation in Ventilated Infants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypothermia Brochure

Visit these websites for more water safety and hypothermia prevention in- formation. What is East Pierce Fire & Rescue Hypothermia? www.eastpiercefire.org Hypothermia means “low temperature”. Washington State Drowning When your body is exposed to cold tem- Prevention Coalition Hypothermia www.drowning-prevention.org perature, it tries to protect itself by keeping a normal body temperature of 98.6°F. It Children’s Hospital & tries to reduce heat loss by shivering and Regional Medical Center In Our Lakes moving blood from your arms and legs to www.seattlechildrens.org the core of your body—head, chest and and Rivers abdomen. Hypothermia Prevention, Recognition and Treatment www.hypothermia.org Stages of Hypothermia Boat Washington Mild Hypothermia www.boatwashington.org (Core body temperature of 98.6°— 93.2°F) Symptoms: Shivering; altered judg- ment; numbness; clumsiness; loss of Boat U.S. Foundation dexterity; pain from cold; and fast www.boatus.com breathing. Boat Safe Moderate Hypothermia www.boatsafe.com (Core body temperature of 93.2°—86°F) Symptoms: Semiconscious to uncon- scious; shivering reduced or absent; lips are blue; slurred speech; rigid n in muscles; appears drunk; slow Eve breathing; and feeling of warmth can occur. mer! Headquarters Station Sum Severe Hypothermia 18421 Old Buckley Hwy (Core body temperature below 86°F) Bonney Lake, WA 98391 Symptoms: Coma; heart stops; and clinical death. Phone: 253-863-1800 Fax: 253-863-1848 Email: [email protected] Know the water. Know your limits. Wear a life vest. By choosing to swim in colder water you Waters in Western Common Misconceptions Washington reduce your survival time. -

Ventilation Patterns Influence Airway Secretion Movement Marcia S Volpe, Alexander B Adams MPH RRT FAARC, Marcelo B P Amato MD, and John J Marini MD

Original Contributions Ventilation Patterns Influence Airway Secretion Movement Marcia S Volpe, Alexander B Adams MPH RRT FAARC, Marcelo B P Amato MD, and John J Marini MD BACKGROUND: Retention of airway secretions is a common and serious problem in ventilated patients. Treating or avoiding secretion retention with mucus thinning, patient-positioning, airway suctioning, or chest or airway vibration or percussion may provide short-term benefit. METHODS: In a series of laboratory experiments with a test-lung system we examined the role of ventilator settings and lung-impedance on secretion retention and expulsion. Known quantities of a synthetic dye-stained mucus simulant with clinically relevant properties were injected into a transparent tube the diameter of an adult trachea and exposed to various mechanical-ventilation conditions. Mucus- simulant movement was measured with a photodensitometric technique and examined with image- analysis software. We tested 2 mucus-simulant viscosities and various peak flows, inspiratory/ expiratory flow ratios, intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressures, ventilation waveforms, and impedance values. RESULTS: Ventilator settings that produced flow bias had a major effect on mucus movement. Expiratory flow bias associated with intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure generated by elevated minute ventilation moved mucus toward the airway opening, whereas in- trinsic positive end-expiratory pressure generated by increased airway resistance moved the mucus toward the lungs. Inter-lung transfer of mucus simulant occurred rapidly across the “carinal divider” between interconnected test lungs set to radically different compliances; the mucus moved out of the low-compliance lung and into the high-compliance lung. CONCLUSIONS: The move- ment of mucus simulant was influenced by the ventilation pattern and lung impedance. -

COVID-19 Pneumonia: Different Respiratory Treatment for Different Phenotypes? L

Intensive Care Medicine EDITORIAL Un-edited accepted proof COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatment for different phenotypes? L. Gattinoni1, D. Chiumello2, P. Caironi3, M. Busana1, F. Romitti1, L. Brazzi4, L. Camporota5 Affiliations: 1Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Medical University of GöttinGen 4Department of Anesthesia, Intensive Care and Emergency - 'Città della Salute e della Scienza’ Hospital - Turin 5Department of Adult Critical Care, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, Health Centre for Human and Applied Physiological Sciences - London Corresponding author: Luciano Gattinoni Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Medical University of Göttingen, Robert-Koch Straße 40, 37075, Göttingen, Germany Conflict of interests: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose NOTE: This article is the pre-proof author’s accepted version. The final edited version will appear soon on the website of the journal Intensive Care Medicine with the following DOI number: DOI 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2 1 Gattinoni L. et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatment for different phenotypes? (2020) Intensive Care Medicine; DOI: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2 Intensive Care Medicine EDITORIAL Un-edited accepted proof The Surviving Sepsis CampaiGn panel (ahead of print, DOI: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5) recently recommended that “mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 should be managed similarly to other patients with acute respiratory failure in the ICU.” Yet, COVID-19 pneumonia [1], despite falling in most of the circumstances under the Berlin definition of ARDS [2], is a specific disease, whose distinctive features are severe hypoxemia often associated with near normal respiratory system compliance (more than 50% of the 150 patients measured by the authors and further confirmed by several colleagues in Northern Italy). -

Gas Exchange

Gas exchange Gas exchange occurs as a result of respiration, when carbon dioxide is excreted and oxygen taken up, and photosynthesis, when oxygen is excreted and carbon dioxide is taken up. The rate of gas exchange is affected by: • the area available for diffusion • the distance over which diffusion occurs • the concentration gradient across the gas exchange surface • the speed with which molecules diffuse through membranes. Efficient gas exchange systems must: • have a large surface area to volume ratio • be thin • have mechanisms for maintaining steep concentration gradients across themselves • be permeable to gases. Single-celled organisms are aquatic and their cell surface membrane has a sufficiently large surface area to volume ratio to act as an efficient gas exchange surface. In larger organisms, permeable, thin, flat structures have all the properties of efficient gas exchange surfaces but need water to prevent their dehydration and give them mechanical support. Since the solubility of oxygen in water is low, organisms that obtain their oxygen from water can maintain only a low metabolic rate. In small and thin organisms, the distance from gas exchange surface to the inside of the organism is short enough for diffusion of gases to be efficient. Diffusion gradients are maintained because gases are continually used up or produced. In larger organisms, simple diffusion is not an efficient way of transporting gases between cells in the body and the gas exchange surface. In many animals a blood circulatory system carries gases to and from the gas exchange surface. The gas-carrying capacity of the blood is increased by respiratory pigments, such as haemoglobin. -

Mechanisms of Pulmonary Gas Exchange Abnormalities During Experimental Group B Streptococcal Infusion

003 I -3998/85/1909-0922$02.00/0 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 19, No. 9, I985 Copyright 0 1985 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Printed in (I.S. A. Mechanisms of Pulmonary Gas Exchange Abnormalities during Experimental Group B Streptococcal Infusion GREGORY K. SORENSEN, GREGORY J. REDDING, AND WILLIAM E. TRUOG ABSTRACT. Group B streptococcal sepsis in newborns obtained from GBS (5, 6). Arterial Poz fell by 9 torr in association produces pulmonary arterial hypertension and hypoxemia. with the increase in pulmonary arterial pressure (4). In contrast, The purpose of this study was to investigate the mecha- the neonatal piglet infused with GBS demonstrated both pul- nisms by which hypoxemia occurs. Ten anesthetized, ven- monary arterial hypertension and profound arterial hypoxemia tilated piglets were infused with 2 x lo9 colony forming (7). These results suggest that the neonatal pulmonary vascula- unitstkg of Group B streptococci over a 30-min period. ture may respond to bacteremia differently from that of adults. Pulmonary arterial pressure rose from 14 ? 2.8 to 38 ? The relationship between Ppa and the matching of alveolar 6.7 torr after 20 min of the bacterial infusion (p< 0.01). ventilation and pulmonary perfusion, a major determinant of During the same period, cardiac output fell from 295 to arterial oxygenation during room air breathing (8), has not been 184 ml/kg/min (p< 0.02). Arterial Po2 declined from 97 studied in newborns. The predictable rise in Ppa with an infusion 2 7 to 56 2 11 torr (p< 0.02) and mixed venous Po2 fell of group B streptococcus offers an opportunity to delineate the from 39.6 2 5 to 28 2 8 torr (p< 0.05). -

The Hazards of Nitrogen Asphyxiation US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board

The Hazards of Nitrogen Asphyxiation US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board Introduction • Nitrogen makes up 78% of the air we breath; because of this it is often assumed that nitrogen is not hazardous. • However, nitrogen is safe to breath only if it is mixed with an appropriate amount of oxygen. • Additional nitrogen (lower oxygen) cannot be detected by the sense of smell. Introduction • Nitrogen is used commercially as an inerting agent to keep material free of contaminants (including oxygen) that may corrode equipment, present a fire hazard, or be toxic. • A lower oxygen concentration (e.g., caused by an increased amount of nitrogen) can have a range of effects on the human body and can be fatal if if falls below 10% Effects of Oxygen Deficiency on the Human Body Atmospheric Oxygen Concentration (%) Possible Results 20.9 Normal 19.0 Some unnoticeable adverse physiological effects 16.0 Increased pulse and breathing rate, impaired thinking and attention, reduced coordination 14.0 Abnormal fatigue upon exertion, emotional upset, faulty coordination, poor judgment 12.5 Very poor judgment and coordination, impaired respiration that may cause permanent heart damage, nausea, and vomiting <10 Inability to move, loss of consciousness, convulsions, death Source: Compressed Gas Association, 2001 Statistics on Incidents CSB reviewed cases of nitrogen asphyxiation that occurred in the US between 1992 and 2002 and determined the following: • 85 incidents of nitrogen asphyxiation resulted in 80 deaths and 50 injuries. • The majority of -

Oxygenation and Oxygen Therapy

Rules on Oxygen Therapy: Physiology: 1. PO2, SaO2, CaO2 are all related but different. 2. PaO2 is a sensitive and non-specific indicator of the lungs’ ability to exchange gases with the atmosphere. 3. FIO2 is the same at all altitudes 4. Normal PaO2 decreases with age 5. The body does not store oxygen Therapy & Diagnosis: 1. Supplemental O2 is an FIO2 > 21% and is a drug. 2. A reduced PaO2 is a non-specific finding. 3. A normal PaO2 and alveolar-arterial PO2 difference (A-a gradient) do NOT rule out pulmonary embolism. 4. High FIO2 doesn’t affect COPD hypoxic drive 5. A given liter flow rate of nasal O2 does not equal any specific FIO2. 6. Face masks cannot deliver 100% oxygen unless there is a tight seal. 7. No need to humidify if flow of 4 LPM or less Indications for Oxygen Therapy: 1. Hypoxemia 2. Increased work of breathing 3. Increased myocardial work 4. Pulmonary hypertension Delivery Devices: 1. Nasal Cannula a. 1 – 6 LPM b. FIO2 0.24 – 0.44 (approx 4% per liter flow) c. FIO2 decreases as Ve increases 2. Simple Mask a. 5 – 8 LPM b. FIO2 0.35 – 0.55 (approx 4% per liter flow) c. Minimum flow 5 LPM to flush CO2 from mask 3. Venturi Mask a. Variable LPM b. FIO2 0.24 – 0.50 c. Flow and corresponding FIO2 varies by manufacturer 4. Partial Rebreather a. 6 – 10 LPM b. FIO2 0.50 – 0.70 c. Flow must be sufficient to keep reservoir bag from deflating upon inspiration 5. -

Clinical Management of Severe Acute Respiratory Infections When Novel Coronavirus Is Suspected: What to Do and What Not to Do

INTERIM GUIDANCE DOCUMENT Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infections when novel coronavirus is suspected: What to do and what not to do Introduction 2 Section 1. Early recognition and management 3 Section 2. Management of severe respiratory distress, hypoxemia and ARDS 6 Section 3. Management of septic shock 8 Section 4. Prevention of complications 9 References 10 Acknowledgements 12 Introduction The emergence of novel coronavirus in 2012 (see http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/en/index. html for the latest updates) has presented challenges for clinical management. Pneumonia has been the most common clinical presentation; five patients developed Acute Respira- tory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). Renal failure, pericarditis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) have also occurred. Our knowledge of the clinical features of coronavirus infection is limited and no virus-specific preven- tion or treatment (e.g. vaccine or antiviral drugs) is available. Thus, this interim guidance document aims to help clinicians with supportive management of patients who have acute respiratory failure and septic shock as a consequence of severe infection. Because other complications have been seen (renal failure, pericarditis, DIC, as above) clinicians should monitor for the development of these and other complications of severe infection and treat them according to local management guidelines. As all confirmed cases reported to date have occurred in adults, this document focuses on the care of adolescents and adults. Paediatric considerations will be added later. This document will be updated as more information becomes available and after the revised Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines are published later this year (1). This document is for clinicians taking care of critically ill patients with severe acute respiratory infec- tion (SARI). -

The Basics of Ventilator Management Overview How We Breath

3/23/2019 The Basics of Ventilator Management What are we really trying to do here Peter Lutz, MD Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Pulmonary Associates, Mobile, Al Overview • Approach to the physiology of the lung and physiological goals of mechanical Ventilation • Different Modes of Mechanical Ventilation and when they are indicated • Ventilator complications • Ventilator Weaning • Some basic trouble shooting How we breath http://people.eku.edu/ritchisong/301notes6.htm 1 3/23/2019 How a Mechanical Ventilator works • The First Ventilator- the Iron Lung – Worked by creating negative atmospheric pressure around the lung, simulating the negative pressure of inspiration How a Mechanical Ventilator works • The Modern Ventilator – The invention of the demand oxygen valve for WWII pilots if the basis for the modern ventilator https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcRI5v-veZULMbt92bfDmUUW32SrC6ywX1vSzY1xr40aHMdsCVyg6g How a Mechanical Ventilator works • The Modern Ventilator – How it works Inspiratory Limb Flow Sensor Ventilator Pressure Sensor Expiratory Limb 2 3/23/2019 So what are the goals of Mechanical Ventilation • What are we trying to control – Oxygenation • Amount of oxygen we are getting into the blood – Ventilation • The movement of air into and out of the lungs, mainly effects the pH and level of CO 2 in the blood stream Lab Oxygenation Ventilation Pulse Ox Saturation >88-90% Arterial Blood Gas(ABG) Po 2(75-100 mmHg) pCO 2(40mmHg) pH(~7.4) Oxygenation How do we effect Oxygenation • Fraction of Inspired Oxygen (FIO 2) – Percentage of the gas mixture given to the patient that is Oxygen • Room air is 21% • On the vent ranges from 30-100% • So if the patient’s blood oxygen levels are low, we can just increase the amount of oxygen we give them 3 3/23/2019 How do we effect Oxygenation • Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP) – positive pressure that will remains in the airways at the end of the respiratory cycle (end of exhalation) that is greater than the atmospheric pressure in mechanically ventilated patients. -

Gas-Liquid Hollow Fiber Membrane Contactors for Different Applications

Review Gas-Liquid Hollow Fiber Membrane Contactors for Different Applications Stepan D. Bazhenov 1,*, Alexandr V. Bildyukevich 2 and Alexey V. Volkov 1 1 A.V. Topchiev Institute of Petrochemical Synthesis, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow 119991, Russia; [email protected] 2 Institute of Physical Organic Chemistry, National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, Minsk 220072, Belarus; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-495-647-5927 (ext. 202) Received: 14 September 2018; Accepted: 2 October 2018; Published: 10 October 2018 Abstract: Gas-liquid membrane contactors that were based on hollow fiber membranes are the example of highly effective hybrid separation processes in the field of membrane technology. Membranes provide a fixed and well-determined interface for gas/liquid mass transfer without dispensing one phase into another while their structure (hollow fiber) offers very large surface area per apparatus volume resulted in the compactness and modularity of separation equipment. In many cases, stated benefits are complemented with high separation selectivity typical for absorption technology. Since hollow fiber membrane contactors are agreed to be one of the most perspective methods for CO2 capture technologies, the major reviews are devoted to research activities within this field. This review is focused on the research works carried out so far on the applications of membrane contactors for other gas-liquid separation tasks, such as water deoxygenation/ozonation, air humidity control, ethylene/ethane separation, etc. A wide range of materials, membranes, and liquid solvents for membrane contactor processes are considered. Special attention is given to current studies on the capture of acid gases (H2S, SO2) from different mixtures. -

Neonatal Ventilation

Neonatal Ventilation Edward G. Shepherd History • Bourgeois, 1609: – “…give a small spoonfulof pure wine into the neonate’s mouth, …[to] help the infant to regain its spirits when being agitated by the labors, which sometimes make it so weak that it seems more dead than alive.” • Mauriceau, mid-1600’s: – “[The baby] should be rested on a warmed bed and brought near the fire, where the midwife having taken some wine into her mouth shall blow it into the infant’s mouth, which can be repeated several times if necessary … She should warm all the parts of the body to recall the blood and the spirits which retired during the weakness and endangered suffocation.” Neonatology 2008;94:144–149 History • Levret, 1766: – “There is one more means which sometimes works as by enchantment, it is to apply one’s mouth on that of the infant and to blow into it, taking care to pinch the tip of the nose simultaneously. This method is so effective that it is really rare that others are useful if it fails” Neonatology 2008;94:144–149 History • First ventilators: – Hunter, Chaussier, and Gorcy in the mid 1700’s • Bellows or gas attached to masks or tubes • 1800’s – Discovery of the breathing center – Determination of survival time in asphyxiated animals – First attempts at electrical resuscitation Neonatology 2008;94:144–149 History • By mid 1800’s ventilation fell out of favor – Fears of pnuemothorax, infection, and sudden death – Various positional techniques were developed • “Schultze swingings” • Arm extension and then chest compression – Stayed in practice -

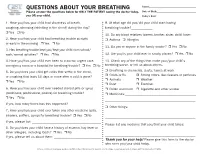

QUESTIONS ABOUT YOUR BREATHING Name:______Please Answer the Questions Below for ONLY the PATIENT Seeing the Doctor Today, Date of Birth:______You OR Your Child

QUESTIONS ABOUT YOUR BREATHING Name:_____________________________________ Please answer the questions below for ONLY THE PATIENT seeing the doctor today, Date of Birth:_______________________________ you OR your child. Today’s Date:_______________________________ 1. Have you/has your child had shortness of breath, 9. At what age did you/did your child start having coughing, wheezing (whistling in the chest) during the day? breathing trouble?_____________ r Yes r No 10. Do any blood relatives (parent, brother, sister, child) have: 2. Have you/has your child had breathing trouble at night r Asthma r Allergies or early in the morning r Yes r No 11. Do you or anyone in the family smoke? r Yes r No 3. Has breathing trouble kept you/kept your child from school/ work/normal activities? r Yes r No 12. Are you/is your child ever in smoky places? r Yes r No 4. Have you/has your child ever been to a doctor, urgent care, 13. Check any of the things that make your/your child’s emergency room or a hospital for breathing trouble? r Yes r No breathing worse, or tell us about others. 5. Do you/does your child get colds that settle in the chest, r Breathing in chemicals, dusts, fumes at work r Colds or flu r Strong odors, like cleaners or perfumes or coughing that lasts 10 days or more after a cold is gone? r Animals r Weather r Yes r No r Dust r Exercise 6. Have you/has your child ever needed steroid pills or syrup r Pollen and mold r Cigarette and other smoke (prednisone, prednisolone, prelone) for breathing trouble? r Medicines:___________________________________________ r Yes r No _______________________________________________________ If yes, how many times has this happened? ___________________ r Other things: 7.