Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 87, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2016 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Royal Historical Society of Victoria is a community organisation comprising people from many fields committed to collecting, researching and sharing an understanding of the history of Victoria. The Victorian Historical Journal is a fully refereed journal dedicated to Australian, and especially Victorian, history produced twice yearly by the Publications Committee, Royal Historical Society of Victoria. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Jill Barnard Marilyn Bowler Richard Broome (Convenor) Marie Clark Mimi Colligan Don Garden (President, RHSV) Don Gibb David Harris (Editor, Victorian Historical Journal) Kate Prinsley Marian Quartly (Editor, History News) John Rickard Judith Smart (Review Editor) Chips Sowerwine Carole Woods BECOME A MEMBER Membership of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria is open. All those with an interest in history are welcome to join. Subscriptions can be purchased at: Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Journals are also available for purchase online: www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ISSUE 286 VOLUME 87, NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 2016 Royal Historical Society of Victoria Victorian Historical Journal Published by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Fax: 03 9326 9477 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Copyright © the authors and the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 2016 All material appearing in this publication is copyright and cannot be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher and the relevant author. -

Geoffrey Laurenson

‘Give a woman a Kodak’ The Doris McKellar Photograph Collection Geoff Laurenson The early 20th century was a time Hall and Harriet ‘Hattie’ Louisa Hall of great social change in Australia, (née Moore). Doris had a privileged building in part on technological upbringing; the family lived at innovations of the late 19th century. ‘Glenmoore’, a spacious, two-storey The University of Melbourne was villa in the south-eastern Melbourne changing as well, since the admission suburb of Elsternwick, situated on of its first women students following a large block, complete with tennis the passing of the University Act court. Glenmoore had been built as a 1881.1 Women also began to enter country house for the Moore family the paid workforce in larger numbers by Hugh Moore, Harriet’s father, in the late 19th century, including around 1868;2 Harriet and Percival the medical profession. This trend Hall probably moved there in 1895, spurred on the opening of the legal following their marriage.3 Doris profession to women through the attended Cromarty School for Girls, passing of the Women’s Disabilities a small, non-denominational private Removal Act in Victoria in 1903, school in Elsternwick, which operated which allowed women to practise as from 1897 to 1923.4 While at barristers and solicitors. Cromarty, Doris took a keen interest The growing popularity of in tennis, representing the school at photography was another significant the Kia-Ora Club matches against development that influenced in gendered terms, with women other girls’ schools.5 She also showed society around this time. Although responsible for documenting matters great academic ability, and was dux of photography had been invented in of domestic or personal significance, the school in 1912.6 In 1915 she sat the mid-19th century, it was not until while men were expected to record her final exams and was accepted into the late 19th century that Kodak more public and political events. -

Australian Women, Past and Present

Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Edited by Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein and Mary Tomsic Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Diversity in leadership : Australian women, past and present / Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein, Mary Tomsic, editors. ISBN: 9781925021707 (paperback) 9781925021714 (ebook) Subjects: Leadership in women--Australia. Women--Political activity--Australia. Businesswomen--Australia. Women--Social conditions--Australia Other Authors/Contributors: Damousi, Joy, 1961- editor. Rubenstein, Kim, editor. Tomsic, Mary, editor. Dewey Number: 305.420994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Introduction . 1 Part I. Feminist perspectives and leadership 1 . A feminist case for leadership . 17 Amanda Sinclair Part II. Indigenous women’s leadership 2 . Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy: Indigenous women leaders in Yolngu, Australia-wide and international contexts . 39 Gwenda Baker, Joanne Garŋgulkpuy and Kathy Guthadjaka 3 . Aunty Pearl Gibbs: Leading for Aboriginal rights . 53 Rachel Standfield, Ray Peckham and John Nolan Part III. Local and global politics 4 . Women’s International leadership . 71 Marilyn Lake 5 . The big stage: Australian women leading global change . 91 Susan Harris Rimmer 6 . ‘All our strength, all our kindness and our love’: Bertha McNamara, bookseller, socialist, feminist and parliamentary aspirant . -

Victorian Honour Roll of Women

INSPIRATIONAL WOMEN FROM ALL WALKS OF LIFE OF WALKS ALL FROM WOMEN INSPIRATIONAL VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE I VICTORIAN HONOUR To receive this publication in an accessible format phone 03 9096 1838 ROLL OF WOMEN using the National Relay Service 13 36 77 if required, or email Women’s Leadership [email protected] Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, 1 Treasury Place, Melbourne. © State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services March, 2018. Except where otherwise indicated, the images in this publication show models and illustrative settings only, and do not necessarily depict actual services, facilities or recipients of services. This publication may contain images of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Where the term ‘Aboriginal’ is used it refers to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Indigenous/Koori/Koorie is retained when it is part of the title of a report, program or quotation. ISSN 2209-1122 (print) ISSN 2209-1130 (online) PAGE II PAGE Information about the Victorian Honour Roll of Women is available at the Women Victoria website https://www.vic.gov.au/women.html Printed by Waratah Group, Melbourne (1801032) VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 2018 WOMEN OF ROLL HONOUR VICTORIAN VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE 1 VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE 2 CONTENTS THE 4 THE MINISTER’S FOREWORD 6 THE GOVERNOR’S FOREWORD 9 2O18 VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN INDUCTEES 10 HER EXCELLENCY THE HONOURABLE LINDA DESSAU AC 11 DR MARIA DUDYCZ -

The Hon Tf Bathurst Chief Justice

THE HON T F BATHURST CHIEF JUSTICE OF NEW SOUTH WALES FRANCIS FORBES SOCIETY AUSTRALIAN LEGAL HISTORY ‘A TOUGH NUT TO CRACK’1: THE HISTORY OF THE LEGAL PROFESSION IN NEW SOUTH WALES THURSDAY 19 SEPTEMBER 2019* INTRODUCTION 1. I would like to begin by respectfully acknowledging the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, the Gadigal people of the Eora nation, and pay my respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging. As I will discuss later in this tutorial, the first legal system in Australia belonged to that of Australia’s Indigenous people. We acknowledge and respect the ongoing laws and customs of the traditional custodians of this land. 2. If any of you are here to hear about the development of the law of New South Wales or the history of its courts, you are sure to be disappointed. To console you there will be plenty of these lectures during the Court’s bicentenary in a few years’ time. This speech is about the profession itself, not the law, Courts or judiciary. 3. A traditional view of the advent of the legal profession in New South Wales would focus exclusively on the advent of solicitors, both free and former- convict, and barristers in the emerging penal Colony. However, far too often we conflate the start of the legal profession in New South Wales with the start of the legal profession for men. The advent of the legal profession for women did not occur until over a century later, and regrettably, even later for Australia’s Indigenous peoples. -

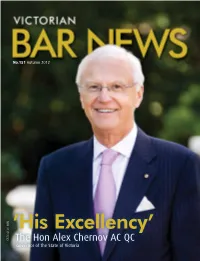

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

Leading from the Bench: Women Jurists As Role Models

Leading from the Bench: Women Jurists as Role Models Remarks by the Honourable Marilyn Warren AC, Chief Justice of Victoria on the occasion of American Chamber of Commerce in Australia ‘Women in Leadership’ Breakfast at Crown, Melbourne 12 February 2015 Précis Women currently account for about one third of the Australian judiciary; an extraordinary achievement in a relatively short time. This figure is echoed in the United States. The Hon. Chief Justice Marilyn Warren AC, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Victoria, celebrates the women who paved the way for judicial equality and who continue to act as role models and inspire others to continue the journey. Introduction Women are a relatively recent addition to the practice of law in Australia. It was just over a century ago in 1902 that Australia saw its first female law graduate, Ada Evans.1 Legend has it that her enrolment at the Sydney Law School was aided by a small stroke of good fortune or, rather, good timing. The Dean of Law at the time would never have accepted a woman, 1 Mary Gaudron, ‘Australian Women Lawyers’ (Speech to delivered at the launch of Australian Women Lawyers, High Court of Australia, 19 September 1997). Supreme Court of Victoria 12 February 2015 however luckily for Evans he was on leave at the time and her enrolment was accepted in his absence.2 Upon his return the Dean told Evans that ‘she did not have the physique for law’.3 However it was too late; Evans was not deterred. History had been made and the trailblazing had begun. -

VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No

VICTORIAN No. 139 ISSN 0159-3285BAR NEWS SUMMER 2006 Appointment of Senior Counsel Welcomes: Justice Elizabeth Curtain, Judge Anthony Howard, Judge David Parsons, Judge Damien Murphy, Judge Lisa Hannon and Magistrate Frank Turner Farewell: Judge Barton Stott Charles Francis Talks of County Court Judges of Yesteryear Postcard from New York City Bar Welcomes Readers Class of 2006 Milestone for the Victorian Bar 2006–2007 Victorian Bar Council Appointment and Retirement of Barfund Board Directors Celebrating Excellence Retiring Chairman’s Dinner Women’s Legal Service Victoria Celebrates 25 Years Fratricide in Labassa Launch of the Good Conduct Guide Extending the Boundary of Right Council of Legal Education Dinner Women Barristers Association Anniversary Dinner A Cricket Story The Essoign Wine Report A Bit About Words/The King’s English Bar Hockey 3 ���������������������������������� �������������������� VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 139 SUMMER 2006 Contents EDITORS’ BACKSHEET 5 Something Lost, Something Gained 6 Appointment of Senior Counsel CHAIRMAN’S CUPBOARD 7 The Bar — What Should We be About? ATTORNEY-GENERAL’S COLUMN 9 Taking the Legal System to Even Stronger Ground Welcome: Justice Welcome: Judge Anthony Welcome: Judge David WELCOMES Elizabeth Curtain Howard Parsons 10 Justice Elizabeth Curtain 11 Judge Anthony Howard 12 Judge David Parsons 13 Judge Damien Murphy 14 Judge Lisa Hannon 15 Magistrate Frank Turner FAREWELL 16 Judge Barton Stott NEWS AND VIEWS 17 Charles Francis Talks of County Court Judges Welcome: Judge Damien Welcome: Judge -

The Case of Edith Haynes*

CHALLENGING THE LEGAL PROFESSION A CENTURY ON: THE CASE OF EDITH HAYNES* † MARGARET THORNTON This article focuses on Edith Haynes’ unsuccessful attempt to enter the legal profession in Western Australia. Although admitted to articles as a law student in 1900, she was denied permission to sit her intermediate examination by the Supreme Court of WA (In re Edith Haynes (1904) 6 WAR 209). Edith Haynes is of particular interest for two reasons. First, the decision denying her permission to sit the exam was an example of a ‘persons’ case’, which was typical of an array of cases in the English common law world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in which courts determined that women were not persons for the purpose of entering the professions or holding public office. Secondly, as all (white) women had been enfranchised in Australia at the time, the decision of the Supreme Court begs the question as to the meaning of active citizenship. The article concludes by hypothesising a different outcome for Edith Haynes by imagining an appeal to the newly established High Court of Australia. Contents I Introduction ................................................................................................1 II Edith Haynes 1876-1963...............................................................................4 III In Re Haynes ..................................................................................................6 IV The Citizenship Conundrum ...........................................................................9 V Imagining -

010Edition 34 1010Victorian Women Lawyers Celebrating 10 Years in 2006

p 10edition 34 Victorian Women Lawyers 1Celebrating0 10 years in 2006 The Objectives of the Association (a) to provide a common meeting ground for women lawyers; (b) to foster the continuing education and development of women lawyers in all matters of legal interest; portia (c) to encourage and provide for the entry of A publication of women into the legal profession and their advancement within the legal profession; (d) to work towards the reform of the law; (e) to participate as a body in matters of interest to the legal profession; C el 6 e 00 br 2 (f) to promote the understanding and support at in ing 10 years of women’s legal and human rights; and (g) such other objectives as the Association may in General Meeting decide. Further, the Association also adopts the objectives Edition 34, August 2006 of the Australian Women Lawyers and is a Recognised Organisation of that Association: (a) achieve justice and equality for all women: Executive Committee (b) further understanding of and support 2006 Convenor Virginia Jay for the legal rights of all women; Immediate Past Convenor Rosemary Peavey (c) identify, highlight and eradicate discrimination Assistant Convenor Justine Lau against women in law and in the legal system; Secretary Anne Winckel (d) advance equality for women in the legal profession; Treasurer Leanne Hughson (e) create and enhance awareness of women’s contribution to the practise Chair Networking and development of the law; and Committee Mandy Bede (f) provide a professional and social Chair Communications network for women -

Final Thesis File

The Children’s Court: Implications of a New Jurisdiction Jennifer Marie Anderson https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5562-6383 Williamstown Police Court c. 1890s with children in foreground Andrew Rider (1821 – 1903), State Library Victoria, H86.98/640. Doctor of Philosophy March 2021 Melbourne Law School and School of Social and Political Studies University of Melbourne Submitted in total fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ABSTRACT This thesis examines the establishment of Children’s Courts in the state of Victoria through the Children’s Court Act 1906 (Vic) and the campaign for legislative change in the city of Melbourne. It asks as its central question why the foundation of a separate Court was, and continues to be, understood as a primary response to children’s social and economic disadvantage. The thesis employs social history methodologies to show, through close jurisprudential examination of archives, how the Children’s Court was theorised by middle class reformers as a solution to their anxieties about the public behaviour of poor urban children in early twentieth-century Melbourne. It reveals how those anxieties were projected on to concerns over Court environment and procedures, as well as how key decisions about which children should be included within (and excluded from) the new jurisdiction reflected reformers’ social and moral understandings about criminal responsibility, poverty and welfare, race and gender. The thesis also documents the experiences of children who were the subject of historical Court intervention. Their life stories demonstrate the close interrelationship between structural disadvantage and a Court appearance. This research project has both historical and contemporary significance. -

How Great Ideas Take Flight INNOVATION an EIGHT-PAGE SPECIAL REPORT

melbourne university magazine How great ideas take flight INNOVATION AN EIGHT-PAGE SPECIAL REPORT ISSUE 1, 2017 JUSTICE FOR ALL A DAY IN THE MAGISTRATES’ COURT 2 ISSUE 1, 2017 CONTENTS 3 unimelb.edu.au/3010 unimelb.edu.au/3010 STAY IN TOUCH We hope you enjoy your exclusive alumni magazine, 3010, packed with news, features and all that’s happening at the University of Melbourne. ISSUE 1, 2017 We have an extensive range of events and benefits available WE WELCOME YOUR FEEDBACK to alumni both locally and Email your comments to: internationally. [email protected] Write to us at: The Advancement Office, Go to unimelb.edu.au/3010 The University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia and stay in touch. Call us on: +61 3 8344 1751 THE ALUMNI For more exclusive content visit: RELATIONS TEAM unimelb.edu.au/3010 EDITORIAL ADVISORY GROUP WANT MORE? DR JAMES ALLAN, DIRECTOR, ALUMNI AND STAKEHOLDER RELATIONS GO ONLINE DORON BEN-MEIR, VICE-PRINCIPAL FOR ENTERPRISE Social media can connect you EOIN HAHESSY, ADVISOR COMMUNICATIONS to many of the University’s AND PUBLIC RELATIONS, ENGAGEMENT 300,000-strong alumni DR JENNIFER HENRY, BEQUESTS MANAGER (BAgr(Hons) 1990, PhD 2001) LA story community. Our alumni are PETER KRONBORG, UNIVERSITY OF A group of driven, represented on all the major MELBOURNE ALUMNI COUNCIL (MBA 1979) young graduates come channels. ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR TIMOTHY LYNCH, Go to alumni.unimelb.edu.au/ GRADUATE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES together in a Hollywood AND SOCIAL SCIENCES alumni/connect SIMON MANN, EDITOR, THE CITIZEN, house to pursue their CENTRE FOR ADVANCING JOURNALISM movie dreams.