Political Dynasties and Personal Political Machines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

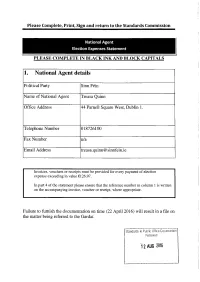

Sinn-Fein-NA-EES.Pdf

Candidate Name Constituency Amount Assigned Total Expenditure on the candidate by the national agent € € 1. Micheal MacDonncha Dublin Bay North 5000 2.Denise Mitchell Dublin Bay North 5000 3.Chris Andrews Dublin Bay South 5000 450.33 4.Mary Lou McDonald Dublin Central 4000 5.Louise O’Reilly Dublin Fingal 8000 2449.33 6. Eoin O’Broin Dublin Mid West 3000 7. Dessie Ellis Dublin North West 3000 8.Cathleen Carney Boud Dublin North West 5000 9.Sorcha Nic Cormaic Dublin Rathdown 5000 10.Aengus Ó Snodaigh Dublin South 3000 Central 11.Màire Devine Dublin South 3000 Central 12. Sean Crowe Dublin South West 3000 13.Sarah Holland Dublin South West 5000 14.Paul Donnelly Dublin West 3000 69.50 15.Shane O’Brien Dun Laoghaire 5000 73.30 16.Caoimhghìn Ó Caoláin Cavan Monaghan 3000 129.45 17.Kathryn Reilly Cavan Monaghan 3000 192.20 18.Pearse Doherty Donegal 3000 19.Pádraig MacLochlainn Donegal 3000 20.Garry Doherty Donegal 3000 21.Annemarie Roche Galway East 5000 22.Trevor O’Clochartaigh Galway West 5000 73.30 23.Réada Cronin Kildare North 5000 24.Patricia Ryan Kildare South 5000 13.75 25.Brian Stanley Laois 3000 255.55 26.Paul Hogan Longford 5000 Westmeath 27.Gerry Adams Louth 3000 28.Imelda Munster Louth 10000 29.Rose Conway Walsh Mayo 10000 560.57 30.Darren O’Rourke Meath East 6000 31.Peadar Tòibìn Meath West 3000 247.57 32.Carol Nolan Offaly 4000 33.Claire Kerrane Roscommon Galway 5000 34.Martin Kenny Sligo Leitrim 3000 193.36 35.Chris MacManus Sligo Leitrim 5000 36.Kathleen Funchion Carlow Kilkenny 5000 37.Noeleen Moran Clare 5000 794.51 38.Pat Buckley Cork East 6000 202.75 39.Jonathan O’Brien Cork North Central 3000 109.95 40.Thomas Gould Cork North Central 5000 109.95 41.Nigel Dennehy Cork North West 5000 42.Donnchadh Cork South Central 3000 O’Laoghaire 43.Rachel McCarthy Cork south West 5000 101.64 44.Martin Ferris Kerry County 3000 188.62 45.Maurice Quinlivan Limerick City 3000 46.Seamus Browne Limerick City 5000 187.11 47.Seamus Morris Tipperary 6000 1428.49 48.David Cullinane Waterford 3000 565.94 49.Johnny Mythen Wexford 10000 50.John Brady Wicklow 5000 . -

Oversight Group of Ireland's Second National Action Plan on Women

Oversight Group of Ireland’s second National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security 2015 - 2018 Independent Chair 1. Nora Owen Nora was a member of Dáil Eireann (Lower House of Parliament) from 1981-1987 and 1989-2002. She has held several political positions over her 20 years in politics including Deputy Leader of Fine Gael Party in 1993 – 2000 and Minister for Justice from 1994-1997. Nora has spent time in Rwanda as a Volunteer with Concern in 1994 and has taken part in Parliamentary training in Africa Asia and Europe with NDI (USA) and AWEPA. Nora serves on the Board as Vice-Chair of Concern Worldwide. She holds a BSc in Chemistry and Biochemistry and a Business Law Certificate. Nora is currently Chair of Justice and Home Affairs committee of Institute of International and European Affairs, and Chair of the Expert Advisory Group on Development Aid reporting to the Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade. Nora has acted as TV Presenter in TV3 programs and presented Mastermind on TV3 as well as a commentator on several radio and TV programs. Government Departments/Statutory Bodies 2. Kevin Kelly Director, Conflict Resolution Unit, OSCE, Council of Europe and UN Co-ordination, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Prior to his current role, Kevin was Director for Emergency & Recovery (Humanitarian Affairs) in the Development Cooperation Division of the Department. Previously he served as Ambassador to Uganda, also accredited to Rwanda, as Director for Africa in Political Division of the Department of Foreign Affairs, as Head of Development in the Embassy of Ireland in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and as Senior Governance Adviser for the World Bank in Addis Ababa. -

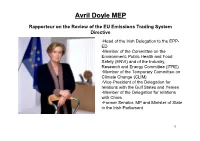

Avril Doyle MEP

Avril Doyle MEP Rapporteur on the Review of the EU Emissions Trading System Directive •Head of the Irish Delegation to the EPP- ED •Member of the Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI) and of the Industry, Research and Energy Committee (ITRE) •Member of the Temporary Committee on Climate Change (CLIM) •Vice-President of the Delegation for relations with the Gulf States and Yemen •Member of the Delegation for relations with China •Former Senator, MP and Minister of State in the Irish Parliament 1 TheThe EUEU ETSETS -- thethe PillarPillar ofof thethe CarbonCarbon MarketMarket • Applicable since 1 January 2005, for 25 EU Member states (now 27 + 3 EEA countries) • Mandatory cap on absolute emissions across more than 10,000 large energy-intensive installations across the Europe • Covers around 2 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions, half of our total emissions • Simple and cost-effective approach to reducing emissions, with single market for trading allowances • Credits from emission-reducing projects in more than 150 countries useable by companies for meeting the reduction target 2 DevelopmentDevelopment ofof EUEU ETSETS (1)(1) • 2005-7: Start-up period - 1st Phase • 2008 -12: 2nd Phase (1st phase under Kyoto) • October 2008: International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP) launched • 23 January 2008: Commission unveils its Climate Package • March 2008: Avril Doyle MEP announced as Rapporteur • 7 October 2008: EP Environment Committee votes on the EU ETS proposal • 17 December 2008: Parliament approves, by overwhelming -

Department of Foreign Affairs Office of the Secretary General 2021 Release 2020/23/1-59

DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY GENERAL 2021 RELEASE 2020/23/1-59 Reference Original Title Date code reference code 2020/23/1 250/630 Secretary General's chronological file, 1986. Letters and Jul 1986-Dec telexes from the Secretary General to embassy officials 1986 and the Department of the Taoiseach. Includes itineraries for Taoiseach Dr Garret FitzGerald's visits, July-December 1986. 2020/23/2 250/635 Secretary General's chronological file, 1986. Letters and Jan 1986-Jun telexes from the Secretary General to embassy officials 1986 and the Department of the Taoiseach. Includes itineraries for Taoiseach Dr Garret FitzGerald's visits, January-June 1986. 2020/23/3 250/897 Anglo-Irish matters, 1981. Includes documents Jan 1981-May (F.27/4) concerning H Block [Her Majesty's Prison Maze, County 1981 Down] hunger strikes; death of Bobby Sands in May 1981. 2020/23/4 250/919 Taoiseach's weekly brief. Brief sent to the Taoiseach from Apr 1982-Jun the Department of Foreign Affairs each week with reports 1986 of meetings, speeches, letters from all sections in the Department. 2020/23/5 250/988 Visit of Taoiseach Dr Garret Fitzgerald to USA, 13-18 Jan 1986-Mar March 1986. Includes itinerary, programme and 1986 arrangements. 2020/23/6 250/989 Anglo-Irish matters. Includes Memorandum for the Jul 1983-Jan Information of the Government, 31 August 1984; 1984 Memorandum for Government on Anglo-Irish relations, 9 May 1984; meetings between Taoiseach Dr Garret FitzGerald and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. 2020/23/7 250/1027 Meeting between Taoiseach Dr Garret FitzGerald and Dec 1986 British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, en Marge of the European Council, London, UK 5-6 December 1986 2020/23/8 250/1038 (A7 German civilian internees. -

74 Dáil Éireann

(Second Supplementary Order Paper) 74 DÁIL ÉIREANN Dé Máirt, 1 Nollaig, 2020 Tuesday, 1st December, 2020 2 p.m. GNÓ COMHALTAÍ PRÍOBHÁIDEACHA PRIVATE MEMBERS' BUSINESS Fógra i dtaobh Leasú ar Thairiscint: Notice of Amendment to Motion [Please note: there is a change to the text of the Sinn Féin motion highlighted in bold on today’s Second Supplementary Order Paper.] 109. “That Dáil Éireann: notes that: — in five weeks’ time the pension age is due to increase to 67 years of age on 1st January, 2021; — legislation needed to stop the pension age increasing to 67 in January has not passed through the House; — every worker in the State makes a considerable tax contribution throughout their working life and should have the right to retire at 65; — some workers want to retire at 65, while others want to remain at work, where they are able and willing to do so; — numerous employment contracts stipulate an end of employment date in line with when an employee turns 65; — since the abolition of the State Pension Transition payment, thousands of 65-year olds have had to sign on for a Jobseeker’s payment; — there are now over 4,000 65-year olds in receipt of either Jobseeker’s Allowance or Jobseeker’s Benefit; — there is a difference of €45.30 between the Jobseeker payments and the State Pension leading to an annual loss of €2,355.60; and — the pension age is scheduled in legislation to increase to 67 years in 2021, and 68 years in 2028; and calls on the Government to: — restore the State Pension Transition payment for those retiring at 65 years of age; — abolish mandatory retirement (with exceptions for security-related employment) to give workers the choice to work or retire so long as they are fit to do so; P.T.O. -

Nationalism in Japan's Contemporary Foreign Policy

The London School of Economics and Political Science Nationalism in Japan’s Contemporary Foreign Policy: A Consideration of the Cases of China, North Korea, and India Maiko Kuroki A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, February 2013 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of <88,7630> words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Josh Collins and Greg Demmons. 2 of 3 Abstract Under the Koizumi and Abe administrations, the deterioration of the Japan-China relationship and growing tension between Japan and North Korea were often interpreted as being caused by the rise of nationalism. This thesis aims to explore this question by looking at Japan’s foreign policy in the region and uncovering how political actors manipulated the concept of nationalism in foreign policy discourse. -

Aguisíní Appendices Aguisín 1: Comóradh Céad Bliain Ollscoil Na Héireann Appendix 1: Centenary of the National University of Ireland

Aguisíní Appendices Aguisín 1: Comóradh Céad Bliain Ollscoil na hÉireann Appendix 1: Centenary of the National University of Ireland Píosa reachtaíochta stairiúil ab ea Acht Ollscoileanna na hÉireann, 1908, a chuir deireadh go foirmeálta le tréimhse shuaite in oideachas tríú leibhéal na hEireann agus a d’oscail caibidil nua agus nuálaíoch: a bhunaigh dhá ollscoil ar leith – ceann amháin díobh i mBéal Feirste, in ionad sean-Choláiste na Ríona den Ollscoil Ríoga, agus an ceann eile lárnaithe i mBaile Átha Cliath, ollscoil fheidearálach ina raibh coláistí na hOllscoile Ríoga de Bhaile Átha Cliath, Corcaigh agus Gaillimh, athchumtha mar Chomh-Choláistí d’Ollscoil nua na hÉirean,. Sa bhliain 2008, rinne OÉ ceiliúradh ar chéad bliain ar an saol. Is iomaí athrú suntasach a a tharla thar na mblianta, go háiriithe nuair a ritheadh Acht na nOllscoileanna i 1997, a rinneadh na Comh-Choláistí i mBaile Átha Cliath, Corcaigh agus Gaillimh a athbhunú mar Chomh-Ollscoileanna, agus a rinneadh an Coláiste Aitheanta (Coláiste Phádraig, Má Nuad) a athstruchtúrú mar Ollscoil na hÉireann, Má Nuad – Comh-Ollscoil nua. Cuireadh tús le comóradh an chéid ar an 3 Nollaig 2007 agus chríochnaigh an ceiliúradh le mórchomhdháil agus bronnadh céime speisialta ar an 3 Nollaig 2008. Comóradh céad bliain ón gcéad chruinniú de Sheanad OÉ ar an lá céanna a nochtaíodh protráid den Seansailéirm, an Dr. Garret FitzGerald. Tá liosta de na hócáidí ar fad thíos. The Irish Universities Act 1908 was a historic piece of legislation, formally closing a turbulent chapter in Irish third level education and opening a new and innovational chapter: establishing two separate universities, one in Belfast, replacing the old Queen’s College of the Royal University, the other with its seat in Dublin, a federal university comprising the Royal University colleges of Dublin, Cork and Galway, re-structured as Constituent Colleges of the new National University of Ireland. -

Dáil Éireann

DÁIL ÉIREANN AN BILLE SLÁINTE (LEASÚ), 2020 HEALTH (AMENDMENT) BILL 2020 LEASUITHE COISTE COMMITTEE AMENDMENTS [No. 42 of 2020] [22 October, 2020] DÁIL ÉIREANN AN BILLE SLÁINTE (LEASÚ), 2020 —AN COISTE HEALTH (AMENDMENT) BILL 2020 —COMMITTEE STAGE Leasuithe Amendments SECTION 3 1. In page 4, line 36, after “Equality” to insert “and Dáil Éireann”. —Bríd Smith, Richard Boyd Barrett, Gino Kenny. 2. In page 4, between lines 36 and 37, to insert the following: “(e) The Minister shall, before prescribing a fixed penalty provision in regulations under this section, recognising the emergency nature of these regulations, consult with and seek approval of a majority of the members of both Houses of the Oireachtas.”. —David Cullinane, Chris Andrews, John Brady, Martin Browne, Pat Buckley, Matt Carthy, Sorca Clarke, Rose Conway-Walsh, Réada Cronin, Seán Crowe, Pa Daly, Pearse Doherty, Paul Donnelly, Dessie Ellis, Mairéad Farrell, Kathleen Funchion, Thomas Gould, Johnny Guirke, Martin Kenny, Claire Kerrane, Pádraig Mac Lochlainn, Mary Lou McDonald, Denise Mitchell, Imelda Munster, Johnny Mythen, Eoin Ó Broin, Donnchadh Ó Laoghaire, Ruairí Ó Murchú, Louise O'Reilly, Darren O'Rourke, Aengus Ó Snodaigh, Maurice Quinlivan, Patricia Ryan, Brian Stanley, Pauline Tully, Mark Ward, Violet-Anne Wynne. 3. In page 5, line 21, after “Equality” to insert “and Dáil Éireann”. —Bríd Smith, Richard Boyd Barrett, Gino Kenny. [No. 42 of 2020] [22 October, 2020] [SECTION 3] 4. In page 5, between lines 21 and 22, to insert the following: “(d) The Minister shall, before prescribing a fixed penalty provision in regulations under this section, recognising the emergency nature of these regulations, consult with and seek approval of a majority of the members of both Houses of the Oireachtas.”. -

Taking Ireland Forward Together CITYWEST HOTEL, DUBLIN 16Th – 17Th November 2018

79th ÁRD FHEIS Taking Ireland Forward Together CITYWEST HOTEL, DUBLIN 16th – 17th November 2018 #FGAF18 CONTENTS Information Connacht/Ulster Candidates 4 17 5 Standing Orders 20 Dublin Candidates 6 What’s Happening 22 Leinster Candidates Message from the Munster Candidates 8 General Secretary 25 General Election Candidates Message from 28 9 An Taoiseach Leo VaradkarTD 30 Accounts Executive Council 10 Nominations 2018 Motions for Debate 32 11 Presidential Candidate 43 Site Maps 12 Vice Presidential Candidates Parliamentary Party Candidates 13 Council of Local Public 16 Representatives Candidates #FGAF18 ARD FHEIS 2018 // 3 INFORMATION REGISTRATION & PRE-REGISTRATION ELECTIONS & VOTING Don’t worry if you haven’t pre-registered for Voting will take place on the Ground Floor of the Árd Fheis. You can still register, but please the Convention Centre between 1.00pm and be aware that you must do so at the Citywest 4.00pm. To vote, members must produce a valid Convention Centre. Membership Card (2018/19) and a Delegate Card and will be asked to produce photo I.D. Registration will take place from 4.00pm to The following are entitled to vote: all Public 8.00pm on Friday and 9.00am to 5.00pm on Representatives, members of Executive Council, Saturday. Constituency and District Officers and five Delegates will be required to produce their delegates per Branch. membership card and photo I.D. Travelling companions will have to be vouched for by a VOTING APPEALS member. The Ethics Committee (Gerry O’Connell, Eileen Lynch, Tom Curran (Gen. Sec), Brian Murphy, COLLECTION OF ACCREDITATION Mary Danagher, Fiona O’Connor, John Hogan) will Delegates who have registered but have not convene in the Carraig Suite between 1.00pm. -

Papers of Gemma Hussey P179 Ucd Archives

PAPERS OF GEMMA HUSSEY P179 UCD ARCHIVES [email protected] www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 © 2016 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Biographical History iv Archival History vi CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and Content vii System of Arrangement ix CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access xi Language xi Finding Aid xi DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s Note xi ALLIED MATERIALS Allied Collections in UCD Archives xi Published Material xi iii CONTEXT Biographical History Gemma Hussey nee Moran was born on 11 November 1938. She grew up in Bray, Co. Wicklow and was educated at the local Loreto school and by the Sacred Heart nuns in Mount Anville, Goatstown, Co. Dublin. She obtained an arts degree from University College Dublin and went on to run a successful language school along with her business partner Maureen Concannon from 1963 to 1974. She is married to Dermot (Derry) Hussey and has one son and two daughters. Gemma Hussey has a strong interest in arts and culture and in 1974 she was appointed to the board of the Abbey Theatre serving as a director until 1978. As a director Gemma Hussey was involved in the development of policy for the theatre as well as attending performances and reviewing scripts submitted by playwrights. In 1977 she became one of the directors of TEAM, (the Irish Theatre in Education Group) an initiative that emerged from the Young Abbey in September 1975 and founded by Joe Dowling. It was aimed at bringing theatre and theatre performance into the lives of children and young adults. -

Transformative Illegality: How Condoms 'Became Legal' in Ireland

Feminist Legal Studies (2018) 26:261–284 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10691-018-9392-1 Transformative Illegality: How Condoms ‘Became Legal’ in Ireland, 1991–1993 Máiréad Enright1 · Emilie Cloatre2 Published online: 20 November 2018 © The Author(s) 2018 Abstract This paper examines Irish campaigns for condom access in the early 1990s. Against the backdrop of the AIDS crisis, activists campaigned against a law which would not allow condoms to be sold from ordinary commercial spaces or vending machines, and restricted sale to young people. Advancing a conception of ‘transformative ille- gality’, we show that illegal action was fundamental to the eventual legalisation of commercial condom sale. However, rather than foregrounding illegal condom sale as a mode of spectacular direct action, we show that tactics of illegal sale in the 1990s built on 20 years of everyday illegal sale within the Irish family planning movement. Everyday illegal sale was a long-term world-making practice, which gradually trans- formed condoms’ legal meanings, eventually enabling new forms of provocative and irreverent protest. Condoms ‘became legal’ when the state recognised modes of con- dom sale, gradually built up over many years and publicised in direct action and in the courts. Keywords Activism · Condoms · Contraceptives · Family planning · Illegality · Ireland · Law · Social movements The Case of the Virgin Condom On Saturday January 6, 1990, Detective-Sergeant John McKeown of Pearse Street Garda (police) Station entered the Virgin Megastore record shop on Aston Quay, near Temple Bar, in Dublin together with a female colleague. They watched as a young woman sold condoms to a young man from a black, semi-circular counter on * Emilie Cloatre [email protected] Máiréad Enright [email protected] 1 Birmingham Law School, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK 2 Kent Law School, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK Vol.:(0123456789)1 3 262 M. -

Palestine in Irish Politics a History

Palestine in Irish Politics A History The Irish State and the ‘Question of Palestine’ 1918-2011 Sadaka Paper No. 8 (Revised edition 2011) Compiled by Philip O’Connor July 2011 Sadaka – The Ireland Palestine Alliance, 7 Red Cow Lane, Smithfield, Dublin 7, Ireland. email: [email protected] web: www.sadaka.ie Bank account: Permanent TSB, Henry St., Dublin 1. NSC 990619 A/c 16595221 Contents Introduction – A record that stands ..................................................................... 3 The ‘Irish Model’ of anti-colonialism .................................................................... 3 The Irish Free State in the World ........................................................................ 4 The British Empire and the Zionist project........................................................... 5 De Valera and the Palestine question ................................................................. 6 Ireland and its Jewish population in the fascist era ............................................. 8 De Valera and Zionism ........................................................................................ 9 Post-war Ireland and the State of Israel ............................................................ 10 The UN: Frank Aiken’s “3-Point Plan for the Middle East” ................................ 12 Ireland and the 1967 War .................................................................................. 13 The EEC and Garret Fitzgerald’s promotion of Palestinian rights ..................... 14 Brian Lenihan and the Irish