Rolling Recessions.” 8 the Cyclical Components of Personal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STOCK MARKET SOLUTION and the STOCK MARKET TRADERS TEST

Copyright © 2006-2017 theHyperDream.com STOCK MARKET SOLUTION and THE STOCK MARKET TRADERS TEST Over 400 Rules and Techniques You Need to Know to Profit at Trading Stocks! by David H Potschka INTRODUCTION It is good to spread stuff out so that your brain doesn't get bored but does get refreshed. I suggest you read the table of contents a few times before you read the book as it will help to prime your memory circuits. Then skim through the entire book without paying much attention to the things you don't understand. Then read the table of contents again a few more times, repeat. Eventually you will have to spend time figuring stuff out but if you pump and prime a few times first it will be easier. Spend a week skimming (like our bankers) so your brain can work on the stuff while you are sleeping at night. I tried to keep the book as short as possible so you could read it in under 5 hours. CONTENTS NOTE: If you can fill in all the "..." then you know the rules pretty good, and are ready to play the game! THE STOCK MARKET TRADERS TEST (and table of contents) Chapter 1; The Banks Are Criminal, we are aware Rule 1: The strength of the economy determines how high or low the market will go. Chapter 2; Back Cover, About Me Chapter 3; What Constitutes The Market Rule 2: The market is made up of some truth and some fiction... Chapter 4; Enterprise Multiple 1 (EM) and Journal Example 1 Rule 3: So a beaten down company with some legs and a good divy is one really good way to go. -

The IT Revolution and the Asian Economies Edward K

The IT Revolution and the Asian Economies Edward K. Y. Chen Keynote Address Asia Forum Nagoya Kanko Hotel 25 May 2001 1. The IT revolution/development and its implications for global economies and Asian economies in particular I would like to point out several implications of the changing nature of technological change. First, human capital is becoming more important than technology. The technology time lag is getting shorter. Technological change is not occurring in breakthroughs as in the Industrial Revolution, but it is occurring as rapid, incremental changes. This has implications for comparative advantage in Asia. Only countries that are rich in human capital--that have adaptive and creative people--will be able to make good use of the technology revolution. Countries that have historically invested heavily in human capital and an educated labor force will be at an advantage. Second, we are seeing a more globalized and fragmented production world because of international sourcing. International sourcing is enhanced by IT, and to some extent by trade and investment liberalization. In particular, the technological time lag in Asia is very short. I argue that under the IT revolution the Flying Geese concept no longer holds. In the past you had to wait for your turn, but now it is a much more open world. I visualize the current situation very much like bidding for tenders, open bidding, so every time a new opportunity arises every country, regardless of the pecking order can submit a tender, and the one submitting the lowest price will get the industry. The situation is much more competitive. -

1 MORNING BRIEFING Go with the Flows

MORNING BRIEFING December 13, 2017 Go With the Flows See the collection of the individual charts linked below. (1) From global energy-led rolling recession in 2015 to recovery in 2016, and boom in 2017-2018 (?). (2) Global manufacturing PMIs are running hot. (3) China’s exports and imports are back to record highs. (4) Citigroup Economic Surprise Index is highly elevated in the US. (5) Odd downward revision in GDPNow. (6) OECD leading indicators led higher by Germany and Brazil. (7) Americans collectively have never been richer as stock prices soar and home values rebound. (8) The Buffett Ratio is back to its previous record high. Global Economy: Synchronized Boom. It’s now widely known that one of the main reasons why global stock markets are soaring is that the global economy is booming. That wasn’t as widely recognized during the second half of 2016, when Debbie, Joe, and I spotted more signs the global energy-led economic slowdown and earnings recession were coming to an end. This year, there is mounting evidence of a global synchronized boom. The pace of economic activity has quickened in both the advanced and emerging economies. Consider the following latest developments: (1) Global PMIs. The JP Morgan global M-PMI has soared from last year’s low of 50.0 during February to 54.0 during November (Fig. 1). Leading the way has been the advanced economies’ M-PMI, which is up from 50.8 to 55.8 over this period. Trailing, but still improving considerably, has been the emerging economies’ M-PMI, up from 48.9 to 51.7 over this period. -

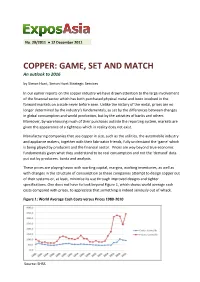

COPPER: GAME, SET and MATCH an Outlook to 2016 by Simon Hunt, Simon Hunt Strategic Services

No. 29/2011 ● 12 December 2011 COPPER: GAME, SET AND MATCH An outlook to 2016 by Simon Hunt, Simon Hunt Strategic Services In our earlier reports on the copper industry we have drawn attention to the large involvement of the financial sector which has both purchased physical metal and been involved in the forward markets on a scale never before seen. Unlike the history of the metal, prices are no longer determined by the industry’s fundamentals, as set by the differences between changes in global consumption and world production, but by the activities of banks and others. Moreover, by warehousing much of their purchases outside the reporting system, markets are given the appearance of a tightness which in reality does not exist. Manufacturing companies that use copper in size, such as the utilities, the automobile industry and appliance makers, together with their fabricator friends, fully understand the ‘game’ which is being played by producers and the financial sector. Prices are way beyond true economic fundamentals given what they understand to be real consumption and not the ‘demand’ data put out by producers, banks and analysts. These prices are playing havoc with working capital, margins, working inventories, as well as with changes in the structure of consumption as these companies attempt to design copper out of their systems or, at least, minimise its use through improved designs and tighter specifications. One does not have to look beyond Figure 1, which shows world average cash costs compared with prices, to appreciate that something is indeed seriously out of whack. Figure 1: World Average Cash Costs versus Prices 1980-2010 Source: SHSS No. -

The Central Role of Home Prices in the Current Financial Crisis: How Will the Market Clear?

11472-03_Case_rev.qxd 3/6/09 12:27 PM Page 161 KARL E. CASE Wellesley College The Central Role of Home Prices in the Current Financial Crisis: How Will the Market Clear? ABSTRACT This paper begins by describing some patterns in home price movements over recent decades. It then discusses some distinguishing char- acteristics of housing markets that will contribute to determining prices going forward: Housing is heterogeneous, making prices hard to measure. Home prices are subject to inertia and are sticky downward. Housing markets have traditionally been quantity clearing markets, with excess inventories absorbed only as new households are formed. And housing markets depend critically on credit market conditions and monetary policy. Two opposite scenarios for future home prices are both plausible: The first, noting among other things the many “underwater” mortgages and unsold inventories and the likelihood of a severe recession, foresees a slow recovery. The second observes that the market clearing process has been orderly so far and that deep regional housing busts in the past have sometimes been followed by quick recoveries, suggesting that a more rapid turnaround is possible. he housing market today lies at the heart of a potentially catastrophic Tcollapse of the banking and financial system. By some measures, hous- ing prices are down by more than even the most pessimistic forecasters were predicting a year ago. The collapse in value of the collateral behind the nation’s $12 trillion portfolio of home mortgages has led to unprecedented rates of delinquency and foreclosure. The decline in home prices has also led investors to unwind the layers of risk created by and traded in new, complex contracts, which now threaten the foundation of the payment system. -

View / Download

CONTENTS Strategic Management and growth economy under the Hammer of Recession and pressures - An Attempt for Understanding a Complex Situation Dr. Muhammad Ali EL-Hajji Seasonality in Stock Markets-Causes and Trends Mohamed Kamara & Mr. Rohit Bahai Causes and Consequences of Global Warming Dr. Urvashi Sharma Micro Finance and Women Empowerment: A Critical Overview Dr. D. Raja Jebasingh Constraints that encounter Strategic Sourcing: A Qualitative Assessment Prof. Ramagopal I & Prof. Lalit Prasad Structure of VAT in Federal Economy of Brazil Dr. Ummed Singh Significant Issues in Cyber Technology Mr. JPS Sirohi & Ms. Rajni Sirohi Lord Krishna Theory of Management in Hospitality Ms. Anju Chaudhary & Ms. Divya Thakur iNTi Green Marketing: Making Sense of the Situation t Ms. Deepmala Jain XGroup'of Institutions '%.:i'5'AT;£VVAY^^T6 KNOWLEDGE I. ' V C'hWderpllflfu^IlifCoTlege of Higher Studies & School of Law Chanderprabhu Jain College of Higher Studies & School of Law, Narela, Delhi - 110040 (Recognized by Govt of NCT of Delhi, Affiliated to Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University, Delhi) V ision About the College “Consistently improving the Chanderprabhu Jain College of Higher Studies (CPJ-CHS) institutional perseverance, & School of Law, has been promoted by the Rishi Aurobindo persistence and patience for Educational Society to start market focused professional ensuring continually rich, programmes in the emerging areas of higher education in value-based and globalize those disciplines which have high growing job potential. careers and lifestyles for all students who enroll themselves The College aims to impart high quality professional for studies in the academic education in a vibrant academic ambience with a faculty of programmes conducted at this distinguished lecturers and resource persons from industry. -

Seven Deadly Sins of Banking

Banks Mike Mayo, CFA Seven deadly sins of banking [email protected] We are initiating on US banks with an Underweight sector rating given (212) 2614000 the ongoing consequences of increased risk taking by banks in seven different areas. A key implication is that loan losses (to total loans) Chris Spahr, CFA should increase to levels that exceed the Great Depression. While certain [email protected] mortgage problems are farther along, other areas are likely to (202) 2979587 accelerate, reflecting a rolling recession by asset class. New government actions might not help as much as expected, especially given that loans have been marked down to only 98 cents on the dollar, on average. Hunter Murchison [email protected] (212) 2614004 Higher Structural Risk ❏ The seven deadly sins of banking include greedy loan growth, gluttony of real Tom Hennessy estate, lust for high yields, sloth-like risk management, pride of low capital, [email protected] envy of exotic fees, and anger of regulators. (212) 2614003 ❏ To a degree, each reflects a way that banks tried to compensate for lower 6 April 2009 natural rates of growth by taking more risk. USA ❏ The effect was to front-load earnings only to have back-ended costs, the brunt which is getting felt today. The consequences of this risk, while not new, seem Banks only midstream and have more to go. Ticker Rating Target Cyclical pressures BAC UNDERPERFORM $8.00 ❏ We expect loan losses to loans to increase from 2% to 3.5% by year-end 2010 BBT SELL $14.00 given ongoing problems in mortgage and an acceleration in cards, consumer C UNDERPERFORM $3.00 credit, construction, commercial real estate and industrial. -

Market Review

MARKET REVIEW Overview of Credit Markets Second Quarter 2009 Report “To rob the public, it is necessary to deceive them. To deceive them, it is necessary to persuade them that they are robbed for their own advantage.” Frédéric Bastiat “The US should consider drafting a second stimulus package focusing on infrastructure projects because the $787 billion approved in February was a bit too small.” Laura Tyson, Member of President Obama’s Economic Recovery Advisory Board Now comes “Son of Stimulus.” Why must there be a second stimulus program, you ask? Well, accord- ing to Laura Tyson, it is because the first stimulus package was just a “bit too small.” Not to be out- quipped, Warren Buffet recently echoed the call for a second stimulus package after referring to the first stimulus bill as “sort of like taking half a tablet of viagra.”So then, we are to understand that the eco- nomic justification for a second stimulus plan is impotence? But how can this be true? Hearken back to January and February of this year and recall what we were told when the first stimulus bill was being crafted. The financial and economic crisis we are now facing was then described by President Obama as “deep and dire as any since the days of the Great Depression.” In fact, the candidate who had run on “hope” spoke in near apocalyptic terms when describing what might befall us if vigorous gov- ernment intervention were not pursued. Mr. Obama warned the American people in no uncertain terms that failure to pass the first stimulus bill “could turn a crisis into a catastrophe.”Yet, set against this backdrop of impending doom and despair, Mr. -

Southwest Economy, Issue 5, September-October, 1997

federal reserve I SSUE 5SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 1997 thwe u s o tt ss e c y onom bank of dallas ROLLING RsECESSIONS EGIONAL ECONOMIES ARE growing across the nation, lead- ing some to observe that this shared national expansion differs considerably from the traditional seesaw of regional downturns and upswings. However, this perception about the past is based on the relatively recent experience of the R 1980s and early 1990s, in which some regions contracted while others expanded. Before then, regional economies tended to move together. What contributed to this out-of-sync behavior? Does the situation differ today? A continuation of this pattern of regional disparities could have significant implications for the national business cycle. Just as the nation is composed of regions, the national business cycle can be thought of as the sum of regional business cycles. If parts of the nation expand while others contract, the nation as a whole may have INSIDE less severe recessions and less volatile business cycles. The current U.S. expansion, along with the expansion of the 1980s, has been ex- Is the Fed Slave to a ceptionally long, far exceeding the four-year average for post–World Defunct Economist? War II expansions. One contributor to this phenomenon may be diverging regional business cycles. Corporate Financing Many factors can cause regional business cycles to differ. For ex- And Governance: ample, national shocks may affect regions differently, due to differ- An International Perspective ing tax and regulatory environments or combinations of labor and capital. Regional cycles are also influ- Chart 1 economic activity as gross domestic enced by shocks specific to the region, Cyclical Components of Real product or the unemployment rate. -

Tracking Budget Surpluses

2/20/2020 Tracking Budget Surpluses I N S I D E T H E VA U LT | S P R I N G 2 0 0 2 https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/inside-the-vault/spring-2002/tracking-budget-surpluses Tracking Budget Surpluses Like all of us, the government's income and spending don't always match. Sometimes the government spends more money than it takes in—a budget deficit. When the opposite occurs, and the government's revenue exceeds expenses, that is known as a budget surplus. Sounds simple, but predicting how long a deficit or surplus will last and which one will occur from year to year has proved to be a complex task for economists. After running deficits that averaged almost $200 billion a year from 1989 to 1997, the federal government recorded a budget surplus of $69.2 billion in fiscal year 1998—the first surplus in more than 25 years. Over the next two years, as the economy strengthened, the federal surplus nearly quadrupled, rising to just under $240 billion in fiscal year 2000. In May 2001, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that it expected this trend to continue in the form of federal surpluses totaling just over $5.6 trillion between fiscal years 2002 and 2011. Unforeseen Obstacles These CBO projections were based on the assumptions that the economy would continue to grow robustly, with no new tax cuts or increases in government spending. Given that trillions of dollars are involved, even small errors in these assumptions about economic conditions have the potential to become quite large when compounded over a decade. -

The Economic Situation 2009

1 THE ECONOMIC SITUATION Bruce Yandle Dean Emeritus, College of Business & Behavioral Science, Clemson University Director, Strom Thurmond Institute Economic Outlook Project [email protected] To add your name to the report email list, please send an email to Kathy Skinner. She is [email protected]. March 2009 Lost trust: How do we move from panic to uncertainty to trust? The bludgeoned economy is seeking a bottom. What about employment? Housing markets: Is the worst behind us? South Carolina journal. Lost trust and financial collapse. The current world financial collapse now has more to do with lost trust than sub-prime mortgages or newly minted monetary and fiscal policy. Indeed, once trust is lost, even the brightest and most articulate political leaders cannot repair the economic engine. It will take real action, not rhetoric to get the engine running smoothly again. In fact, the more rhetoric we get, the less trust we seem to have. What do I mean by lost trust? How did it happen? And what can be done about it? As background, I am referring to the tightly linked world financial market that made it possible for U.S. mortgage backed securities and collateralized debt obligations to be sold to investors worldwide. Bankers and investors in Helsinki, Tokyo, Singapore, and Dubai seemed glad to invest in mortgages that were originated in Florida, Georgia, California, and Nevada without even checking to see where the underlying property or borrowers were located. They had no reason to worry. The paper was rated AAA by the world premier credit rating agencies---Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch. -

Coronavirus Economic Recuperation Continues: New Jersey and the Nation--Not Yet Back to the Future

Please do not remove this page Coronavirus economic recuperation continues: New Jersey and the nation--not yet back to the future Hughes, James W.; Hughes, Connie O.; Seneca, Joseph J. https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643442160004646?l#13643548690004646 Hughes, J. W., Hughes, C. O., & Seneca, J. J. (2020). Coronavirus economic recuperation continues: New Jersey and the nation--not yet back to the future. Rutgers University. https://doi.org/10.7282/t3-k7qx-ym92 This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/24 23:04:14 -0400 Fast Track Research Notes Issue Number 5: September 2020 Coronavirus Economic Shocks: CoronavirusNJ vs The Nation Economic Recuperation Continues: [DOCUMENT SUBTITLE] New Jersey and the Nation—Not Yet Back to the Future James W. Hughes Connie O. Hughes Joseph J. Seneca University Professor Former Chief, Management & University Professor Emeritus Dean Emeritus of the Policy, NJ Governor’s Office Vice President for Academic Edward J. Bloustein Former President & Commissioner Affairs Emeritus School of Planning NJ Board of Public Utilities Distinguished Professor of and Public Policy Former Deputy Commissioner Economics Emeritus Rutgers, The State University NJ Department of Labor Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey of New Jersey Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Coronavirus Economic Recuperation Continues: New Jersey and the Nation—Not Yet Back to the Future The economy of the United States continues to mend from its coronavirus-driven collapse, but the employment surge that characterized the early stages of the recovery has been noticeably tapering off.