The Korean Lutherans' Perspective of Lutheranism and Lutheran Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Give Us Today Our Daily Bread Official Report

LWF EleVENTH ASSEMBLY Stuttgart, Germany, 20–27 July 2010 Give Us Today Our Daily Bread Official Report The Lutheran World Federation – A Communion of Churches Give Us Today Our Daily Bread Official Report THE LUTHERAN WORLD FEDERATION – A COMMUNION OF CHURCHES Published by The Lutheran World Federation Office for Communication Services P.O. Box 2100 CH-1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.lutheranworld.org Parallel editions in German, French and Spanish Unser tägliches Brot gib uns heute! – Offizieller Bericht Donne-nous aujourd’hui notre pain quotidien – Rapport officiel Danos Hoy Nuestro Pan de Cada Día – Informe Oficial Editing, translation, revision, cover design and layout by LWF Office for Communication Services Other translation, revision by Elaine Griffiths, Miriam Reidy-Prost and Elizabeth Visinand Logo design by Leonhardt & Kern Agency, Ludwigsburg, Germany All Photos © LWF/Erick Coll unless otherwise indicated © 2010 The Lutheran World Federation Printed in Switzerland by SRO-Kundig on paper certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (www.fsc.org) ISBN 978-2-940459-08-7 Contents Foreword .......................................................................................7 Address of the LWF President .......................................................9 Address of the General Secretary ...............................................19 Report of the Treasurer ..............................................................29 Letter to the Member Churches .................................................39 -

LWF 2019 Statistics

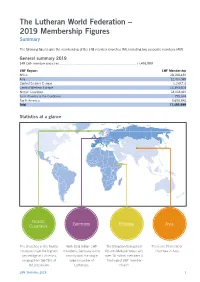

The Lutheran World Federation – 2019 Membership Figures Summary The following figures give the membership of the 148 member churches (M), including two associate members (AM). General summary 2019 148 LWF member churches ................................................................................. 77,493,989 LWF Regions LWF Membership Africa 28,106,430 Asia 12,4 07,0 69 Central Eastern Europe 1,153,711 Central Western Europe 13,393,603 Nordic Countries 18,018,410 Latin America & the Caribbean 755,924 North America 3,658,842 Total 77,493,989 Statistics at a glance Nordic Countries Germany Ethiopia Asia The churches in the Nordic With 10.8 million LWF The Ethiopian Evangelical There are 55 member countries have the highest members, Germany is the Church Mekane Yesus with churches in Asia. percentage of Lutherans, country with the single over 10 million members is ranging from 58-75% of largest number of the largest LWF member the population Lutherans. church. LWF Statistics 2019 1 2019 World Lutheran Membership Details (M) Member Church (AM) Associate Member Church (R) Recognized Church, Congregation or Recognized Council Church Individual Churches National Total Africa Angola ............................................................................................................................................. 49’500 Evangelical Lutheran Church of Angola (M) .................................................................. 49,500 Botswana ..........................................................................................................................................26’023 -

Policy Statement on Foreign Relations of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria

Policy Statement on Foreign Relations of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria A Contribution to the Global Communio Contents Foreword by Michael Martin 4 1. WHY? Foundations 6 1.1 Reasons for ELCB’s Global Ecumenical Work 6 1.2 Entities Responsible for the Partnerships within the ELCB 8 1.3 Priorities of the ELCB’s Partnerships 10 1.4 Context of the Partnerships 11 1.5 Incentives for the ELCB´s Foreign Relations 12 1.6 Challenges, Disparities, Power Issues 12 2. HOW? The ELCB’s Policy Statement on Foreign Relations 14 2.1 The Diversity of Relationships – Partnership is “Journeying Together, Side by Side” 14 2.2 Church in Relationship – The Emmaus Process 14 2.3 Characteristics of Partnership 15 2.4 Principles of Partnership 16 2.5 Partnership and Development – Partners in the Development Process 18 2.6 Forms of Church and Partner Cooperation 20 2.6.1 Partnership Cooperation 20 2.6.1.1 Contractual Partnership 21 2.6.1.2 Partnerships Resulting from Bavarian Missions 21 2.6.1.3 Partner Relationships in Forums 22 2.6.1.4 Amicable and Neighborly Relationships 22 2.6.1.5 Church-Reconstruction Assistance and Temporary Cooperation 23 2.6.1.6 Issue-Based Partnership 23 2.6.2 Ecumenical Cooperation 24 2.6.2.1 The Global Lutheran Community 24 2.6.2.2 Congregations of Various Languages and Origins 24 2.6.2.3 Interconfessional Cooperation 25 2.6.3 Project Support within Partner Relationships 25 2 3. FOR WHAT PURPOSE? Communio as a Vision of Church 27 3.1. -

A Handbook of Councils and Churches Profiles of Ecumenical Relationships

A HANDBOOK OF COUNCILS AND CHURCHES PROFILES OF ECUMENICAL RELATIONSHIPS World Council of Churches Table of Contents Foreword . vii Introduction . ix Part I Global World Council of Churches. 3 Member churches of the World Council of Churches (list). 6 Member churches by church family. 14 Member churches by region . 14 Global Christian Forum. 15 Christian World Communions . 17 Churches, Christian World Communions and Groupings of Churches . 20 Anglican churches . 20 Anglican consultative council . 21 Member churches and provinces of the Anglican Communion 22 Baptist churches . 23 Baptist World Alliance. 23 Member churches of the Baptist World Alliance . 24 The Catholic Church. 29 Disciples of Christ / Churches of Christ. 32 Disciples Ecumenical Consultative Council . 33 Member churches of the Disciples Ecumenical Consultative Council . 34 World Convention of Churches of Christ. 33 Evangelical churches. 34 World Evangelical Alliance . 35 National member fellowships of the World Evangelical Alliance 36 Friends (Quakers) . 39 Friends World Committee for Consultation . 40 Member yearly meetings of the Friends World Committee for Consultation . 40 Holiness churches . 41 Member churches of the Christian Holiness Partnership . 43 Lutheran churches . 43 Lutheran World Federation . 44 Member churches of the Lutheran World Federation. 45 International Lutheran Council . 45 Member churches of the International Lutheran Council. 48 Mennonite churches. 49 Mennonite World Conference . 50 Member churches of the Mennonite World Conference . 50 IV A HANDBOOK OF CHURCHES AND COUNCILS Methodist churches . 53 World Methodist Council . 53 Member churches of the World Methodist Coouncil . 54 Moravian churches . 56 Moravian Unity Board . 56 Member churches of the Moravian Unity Board . 57 Old-Catholic churches . 57 International Old-Catholic Bishops’ Conference . -

The Church's Mission and Evangelistic Task

ACELC Free Conference March 2, 2011 Rev. Clint K. Poppe The Church’s Mission and Evangelistic Task A Distinctively Lutheran Theology of Mission1 “Who am I? Why am I here?”2 It is not easy to be a Lutheran. At times we seem to have no identity of our own. While Roman Catholics see us as just another type of Protestantism, Protestants look at us as watered down Romanists. As Lutherans, we have a unique theological system with an identity all our own. When we forget this basic premise, we always get ourselves into theological trouble. When we fail to keep God’s theological tensions in balance, we not only lose our identity, we fall into error. Perhaps nowhere is this more true than with regard to the topic that is before us today. What is the mission of the Church? Does “mission” have a separate and unique theology of its own? Does being a “Confessional Lutheran” mean you are by definition “anti-mission?” Does having a “heart for mission” mean that there are some traditional Lutheran practices that must be jettisoned? Is it really possible in this day and age to keep the message straight and get the message out? Has it ever been? May God grant us His blessing and guide us into His Truth. The Theology of Mission Where should we begin? The faddish temptation is to begin our discussion of mission with a mission statement. But which statement should we use; synod, district, circuit, congregation, growing congregation, traditional congregation, high priced consultant? The now sainted Dr. -

ILC to EECMY 15Feb2013

INTERNATIONAL LUTHERAN COUNCIL Bishop Hans-Jörg Voigt, Chairman P.O. Box 690407 • 30613 Hannover GERMANY Telephone: 49-511-55-7808 • FAX: 49-511-55-1588 E-MAIL: [email protected] Rev. Dr. Albert B. Collver, III, Executive Secretary 1333 S. Kirkwood Road • St. Louis, MO USA 63122 Telephone: 314-996-1430 • FAX: 314-996-1119 E-MAIL: [email protected] 15 February 2013 Dear President Idosa and the members of the Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus (EECMY): To the church of God in Ethiopia, Grace be unto you, and peace, from God our Father, and from the Lord Jesus Christ. We, the members of the International Lutheran Council and the attendees of the African Lutheran Theological Conference held in Accra, Ghana, on 12 - 15 February 2013, heard the report of the EECMY to severe fellowship with both the Church of Sweden and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America (ELCA) over the issue of same-sex marriage and the ordination of practicing homosexuals into the pastoral ministry. We want to commend and thank you for taking a stand on the Word of God. In fact, we praise the Lord that he has brought this good work to fruition in the life of your church. Your conscience- bound view that the Scripture Alone is the only source of authority in deciding this matter is the view shared by the members of the International Lutheran Council (ILC). We pray that the courage you displayed in standing upon the Word of God will spread to other churches in Africa as they struggle on how to approach historic partners who have departed from the Word of God. -

Lutheran World Includes Informationlwi Membership of Churches Highlights Belonging to the LWF Tops

Assembly Update No. 6 Lutheran World Includes InformationLWI Membership of Churches Highlights Belonging to the LWF Tops The Lutheran World Federation 70 Million for the First Time 2009 Membership Figures ......5 North America Europe 4,784,089 37,164,411 2009 World Lutheran Membership Details ...............6 Lutheran Leader Urges Asian Churches to Expose Systemic Causes of Hunger ................ 14 Asia As the ancient prophets challenged 8,746,434 the powerful who ignored the cries of the needy, so too must the church today act to dismantle systems that prevent people from getting their Latin America daily bread... & the Caribbean 837,692 Africa 18,520,690 North American Church © LWF Leaders Must Become LWF 2009 Membership Figures “Communion Ambassadors” ..20 Lutheran leaders from North America explored what it means to be a communion of communities in a globalizing world at a Lutheran Over 1.2 Million New Members in African World Federation regional seminar 1-12 December in Geneva, Lutheran Churches Switzerland... GENEVA (LWI) – The total number of ognized congregations and one recognized members in churches belonging to the council in 79 countries, had a combined FEATURE: From a Disaster Lutheran World Federation (LWF) last membership increase of approximately 2.3 Graveyard into a Thriving year rose by 1,589,225 to just over 70 percent in 2009. In 2008, LWF affiliated Community ..........................23 Mr Anjappan Kumar remembers million (70,053,316). While membership churches had some 68.5 million members the day five years ago when the of Lutheran churches in Africa and Asia worldwide, up from 68.3 million in 2007. -

LWI-200801-EN-Low.Pdf

Lutheran World InformationLWI Global Increase in LWF Churches’ Highlights Membership Pushes Total to 68.3 Million New Resource Equips North America Churches to Talk About HIV Europe Prevention .............................2 4,958,203 37,137,374 The Geneva-based Ecumenical Advocacy Alliance has released a new guide aimed at helping Christians to talk openly and accurately, and with compassion about why HIV spreads... Asia 8,275,418 The Lutheran World Federation 2007 Membership Figures ......5 Latin America & the Caribbean 2007 World Lutheran 822,074 Africa Membership Details ...............6 17,129,230 © LWF The Lutheran World Federation LWF 2007 Membership Figures Consultations 2008 ..............14 LWF German National Committee Closes Stuttgart An Additional Two Million Members Office ...................................16 in Africa’s Lutheran Churches After some 50 years, the German National Committee of the GENEVA (LWI) Lutheran World Federation has – Africa’s Lutheran churches 1,623,024 to approximately 71.8 million relocated its previously Stuttgart- saw their total membership increase over (71,823,423), an increase of 2.3 percent. In based Office for Church the past year by just under two million, 2006, all Lutheran churches worldwide Cooperation and World Service boosting the total membership of the Lu- counted some 70.2 million members, up from to the United Evangelical theran World Federation (LWF) member 69.8 million in 2005. The number of Luther- Lutheran Church of Germany churches worldwide to over 68.3 million. ans in non-LWF member churches fell by central office in Hanover... Lutheran churches in Asia registered an 17,676, or 0.5 percent, to reach 3,501,124. -

April Journal.P65

CONCORDIA JOURNAL Volume 28 April 2002 Number 2 CONTENTS ARTICLES Pursuit of a Lutheran Raison d’Être in Asia Won Yong JI ............................................................................ 126 “Real Presence”: An Overview and History of the Term Albert B. Collver, III .............................................................. 142 The Aleppo Statement: A Proposal That May “Serve the Cause of Christian Unity” Edward J. Callahan ..................................................................... 160 REVIEW ESSAYS ................................................................................ 175 HOMILETICAL HELPS ..................................................................... 192 BOOK REVIEWS ............................................................................... 216 BOOKS RECEIVED ........................................................................... 230 CONCORDIA JOURNAL/APRIL 2002 125 Articles Pursuit of a Lutheran Raison d’Être in Asia Won Yong JI We are to deal with a serious subject on the reason for existence of Lutherans in Asia. Lutherans are the minority of minorities in the Asian context, with the possible exception of Papua New Guinea, in the midst of most of the leading historical world religions and among relatively large constituencies of Roman Catholic and other Protestant denominations— the “Reformed” oriented, theologically speaking. Furthermore, Lutherans are surrounded by the general milieu of the so-called Charismatic groups which are frequently not compatible with Lutheranism. In -

Report of Actions

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 2 The Commitment 4 Summary of Actions 6 Challenges and Opportunities Encountered 16 What Difference has it Made to Me, and to 21 the People and Community I Serve Lessons, Observations, Recommendations 23 to Other Religious Leaders Reflections on the Report 27 Appendix I 30 Signatures to Together We Must Do More: My Personal Commitment to Action Appendix II 37 Strengthening Religious Leadership Working Group Report on Together We Must Do More 1 www.hivcommitment.net INTRODUCTION In March 2010, some 40 Baha’í, Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim and Sikh leaders met together with the Executive Directors of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the AIDS Ambassadors of The Netherlands and Sweden, leaders and representatives of networks of people living with HIV and other organisations active in the response to HIV. It was the first international, high level meeting aimed at building collaboration and momentum between religious leaders and among religious leaders and other sectors of the response. Participants affirmed in their concluding statement the “renewed sense of urgency” to prioritize and strengthen the response to HIV. Such response includes “holistic prevention” in addition to reaching universal access to treatment, care and support. The statement called for the “respect for the dignity of every human being” as well as “a massive social mobilization” to support services for women to eliminate the transmission of HIV from mother to child. In addition religious leaders drafted and personally signed a pledge to commit themselves to strengthened efforts to respond to HIV. -

Dial Toc 1..2

138 Dialog: A Journal of Theology . Volume 45, Number 2 . Summer 2006 The Lutheran Confessions in Korea By Jin-Seop Eom Abstract: Although Christianity has been active in Korea for two centuries, the church of the Lutheran confessions was planted only a half century ago, in 1958, by the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod. With an ecumenical face, Korean Lutherans provide a dynamic leaven in wider society and the church is growing. Even though other Korean church bodies have engaged in writing new confessional statements, Lutherans are finding the richness of the Lutheran Confessions in the Book of Concord sufficient for self-understanding and expansion. Key Terms: Confession, Lutheran, Korea. In Caesarea Philippi Jesus asked his disciples, ‘‘Who do was introduced approximately one hundred years you say that I am?’’ We know what Peter replied: ‘‘You later, pioneered by Presbyterians and Methodists are the Christ, the Son of the Living God’’ (Matt. from North America (1885). Seventy-three years 16:13–16). This is the question each generation must later (1958) Lutheranism came to Korea through answer. Faith, Philip Schaff says, ‘‘has a desire to express the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod in America. itself before others.’’1 ‘I believe; therefore I confess’ As result of that missionary effort, the Lutheran (Credo, ergo Confiteor). This is exemplified by a Korean Church in Korea was established in 1971 as an pastor in the early part of the twentieth century who used autonomous national church. It continues to this to shout in the streets with eschatological urgency, day as the only national Lutheran church body in ‘‘Believe in Jesus and [go to] Heaven!,’’ later shortened the country. -

Lutheran W Orld Information

2011 World Lutheran Membership Details Lutheran World Information (M) ............................................................................................................. Member Church (AM) .......................................................................................... Associate Member Church (R) ...........................................Recognized Church, Congregation or Recognized Council (C) .........................................................Other Lutheran churches, bodies or congregations Church Individual Churches National Total Africa Angola ................................................................................................................... 48,000 Evangelical Lutheran Church of Angola (M) ........................................................................... 48,000 Botswana .............................................................................................................. 18,800 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Botswana (M) ........................................................................18,800 Burundi ................................................................................................................... 1,850 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Burundi (C) ..............................................................................1,850 Cameroon ............................................................................................................ 406,702 Church of the Lutheran Brethren of Cameroon (M) ..............................................................