A New Paradigm for C-School Ranking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Monthly 2018 College Rankings

The Prison-to-School Pipeline 2018 COLLEGE RANKINGS What Can College Do For You? PLUS: The best—and worst— colleges for vocational certificates Which colleges encourage their students to vote? Why colleges should treat SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 $5.95 U.S./$6.95 CAN students like numbers All Information Fixing higher education deserts herein is confidential and embargoed Everything you always wanted to know through Aug. 23, 2018 about higher education policy VOLUME 50 NUMBER 9/10 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 SOCIAL MOBILITY RESEARCH SERVICE Features NATIONAL UNIVERSITIES THE 2018 COLLEGE GUIDE *Public institution Introduction: A Different Kind of College Ranking 15 °For-profit institution by Kevin Carey America’s Best and Worst Colleges for%offederalwork-studyfunds Vocational Certificates 20 GraduationGrad rate rate rank performancePell graduationPell rank performance gap rankFirst-gen rank performancerankEarningsperformancerankNoNetpricerank publicationRepaymentrankPredictedrepaymentraterankResearch has expendituresBachelor’stoPhDrank everScience&engineeringPhDsrank rank rankedFacultyawardsrankFacultyinNationalAcademiesrank thePeaceCorpsrank schoolsROTC rank wherespentonservicerankMatchesAmeriCorpsservicegrants? millionsVotingengagementpoints of Americans 1 Harvard University (MA) 3 35 60 140 41 2seek 5 168 job310 skills.8 Until10 now.17 1 4 130 188 22 NO 4 2 Stanford University (CA) 7 128 107 146 55 11 by2 Paul16 48Glastris7 6 7 2 2 70 232 18 NO 1 3 MA Institute of Technology (MA) 16 234 177 64 48 7 17 8 89 13 2 10 3 3 270 17 276 NO 0 4 Princeton University (NJ) 1 119 100 100 23 20 Best3 30 &90 Worst67 Vocational5 40 6 5 Certificate117 106 203 ProgramsNO 1 Rankings 22 5 Yale University (CT) 4 138 28 121 49 22 America’s8 22 87 18Best3 Colleges39 7 9 for134 Student22 189 VotingNO 0 28 6 Duke University (NC) 9 202 19 156 218 18 Our26 15 first-of-its-kind183 6 12 list37 of9 the15 schools44 49doing215 theNO most3 to turn students into citizens. -

The Stability of US News' Ranking System Robert Daly

1 Running to Stay in Place: The Stability of U.S. News’ Ranking System Robert Daly, University of California, Riverside Anne Machung, University of California, Office of the President Gina Roque, University of California, Riverside Abstract The ranks of most national universities in the annual U.S. News “America’s Best Colleges” have not changed significantly during the past eight years. This is true even though most national universities have spent considerable resources and energy trying to improve their ranks. In this paper, we document the stability of the national universities’ ranks since 1999, describe how a few private universities have been able to improve their ranks, and discuss whether or not these techniques can be used by other colleges and universities, especially public ones. Introduction: In 1983, U.S. News published its first rankings of colleges and universities, and except for 1984 and 1986 has ranked colleges and universities every subsequent year.1 The 1983 and 1985 rankings were based on academic reputation alone, but in 1987 U.S. News reduced the weight of academic reputation to 25% of its total score, and introduced a series of other measures which it combined into a single quantitative formula. The formula worked. U.S. News rankings have been enormously successful, so much so that they have spawned a whole cottage industry of emulators and competitors – the Washington Monthly rankings, TheCenter rankings from the University of Florida, Maclean’s rankings of Canadian universities, the TimesHigher Education Supplement’s rankings from London, and from the Institute of Higher Education at Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China a list of the top 500 universities in the world. -

PBPL 5: INTRODUCTION to PUBLIC POLICY Winter 2016 Term—Rockefeller 003

Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for Public Policy and the Social Sciences Dartmouth College PBPL 5: INTRODUCTION TO PUBLIC POLICY Winter 2016 Term—Rockefeller 003 Professor Ronald G. Shaiko 10: MWF 10:00-11:05am 204 Rockefeller Hall X-Hour: Thursday, 12:00-12:50pm Tel: 646-9146 Office Hours: MWF 12:00-2:00pm Email: [email protected] and by appointment Course Philosophy: Public policymaking in the United States is characterized by scholars and politicians in a wide variety of ways. For some, public policy reflects “the authoritative allocation of values;” while others see the policymaking process from a more bottom line perspective—“who gets what, when, and how.” Still others have incorporated the overtly political nature of public policy by referring to the process as “partisan mutual adjustment,” and have acknowledged that public policymaking involves trade-offs and, at times, less than optimal policy outcomes—“satisficing.” Those who make public policy in the United States often wrestle with normative questions of what constitutes the “best” policy outcomes for the most people as they strive to reach the right balance between government intervention and citizens’ rights to “the pursuit of happiness.” James Madison clearly stated in the Federalist Papers that “if men were angels, no government would be necessary.” Unfortunately, citizens of the United States are not angels and, as a result, must be constrained in their self-interested pursuits. Public policy—influenced by economics, psychology, sociology, philosophy, political science, and religion—reflects the aspiration of creating a society in which its citizens behave in a way that reflects the broadly agreed upon societal norms and values, but also the day-to- day rules and regulations established by governments at all levels. -

Stanley B. Greenberg the Battle for Working People Begins with Government Reform

Featuring an analysis by: Stanley B. Greenberg The Battle for Working People Begins with Government Reform with a Roundtable Discussion by: Ed Kilgore Ruy Teixeira and John Halpin John Judis Mark Schmitt Joan Walsh Karen Nussbaum Richard D. Kahlenberg Andrew Levison John Russo Jack Metzgar with a welcome by Ed Kilgore and Andrew Levison Welcome to the second white working class roundtable, a project of The Democratic Strategist in collaboration with the Washington Monthly. The first white working class roundtable, held in June 2014, brought together 15 leading pro-Democratic strategists and observers to discuss the subject of “progressives and the white working class” and had a very significant effect on the national debate regarding the white working class vote that emerged after the 2014 elections. The roundtable was directly cited by Thomas Edsall in The New York Times, E.J. Dionne in The Washington Post, Noam Scheiber in The New Republic, Kevin Drum in Mother Jones, Jamelle Bouie in Slate and was cited by many other commentaries that used data and quotes drawn from the contributions to the June 2014 roundtable discussion. As a follow-up to this debate, The Democratic Strategist published an in-depth review of the post-2014 discussion in December, 2014. It is available HERE.i The present White working class roundtable is organized around a provocative strategy paper by leading opinion analyst Stan Greenberg that is entitled, “The Fight for Working People Begins with Government Reform.” Stan’s analysis, which also appears in the June issue of the Washington Monthly, is discussed by a distinguished group of progressive thinkers including Ed Kilgore, Ruy Teixeira, John Halpin, John Judis, Mark Schmitt, Joan Walsh, Karen Nussbaum, Richard Kahlenberg, Andrew Levison and others. -

International Rankings and the Contest for University Hegemony

This article was downloaded by: [UNAM Ciudad Universitaria] On: 26 November 2014, At: 08:29 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Education Policy Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tedp20 International rankings and the contest for university hegemony Imanol Ordorikaa & Marion Lloyda a Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Dirección General de Evaluación Institutional, Circuito del Estadio Olímpico Universitario s/n (costado poniente), antigua tienda UNAM, Ciudad Universitaria, México, México Published online: 24 Nov 2014. To cite this article: Imanol Ordorika & Marion Lloyd (2014): International rankings and the contest for university hegemony, Journal of Education Policy, DOI: 10.1080/02680939.2014.979247 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2014.979247 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Download Curriculum Vitae

JUDITH SCOTT-CLAYTON TEACHERS COLLEGE, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY / COMMUNITY COLLEGE RESEARCH CENTER 525 W. 120TH ST., BOX 174 ∙ NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10027 TEL: (212) 678-3478 ∙ E-MAIL: [email protected] ∙ Twitter: @jscottclayton URL: http://www.tc.columbia.edu/academics/?facid=js3676 EMPLOYMENT 2015 – present TEACHERS COLLEGE, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, Associate Professor of Economics and Education, Dept. of Education Policy and Social Analysis 2009 – 2015 TEACHERS COLLEGE, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, Assistant Professor 2009 – present COMMUNITY COLLEGE RESEARCH CENTER, Senior Research Scholar PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2011 – present NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH, Research Associate since 2017 2015 – present EDUCATION FINANCE AND POLICY, Editorial Board 2016 – present EDUCATIONAL EVALUATION AND POLICY ANALYSIS, Editorial Board EDUCATION 2009 HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT, Ph.D. in Public Policy 2000 WELLESLEY COLLEGE, B.A., Sociology (Economics minor) summa cum laude 1999 LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS, General Course (visiting student) TEACHING & ADMINISTRATION Program Director, Economics & Education MA, EdM & PhD programs. Teaching: Economics of Education, Causal Methods for Education Policy Research, Applied Labor Economics GRANTS & FELLOWSHIPS 2015 Spencer Foundation Grant #201500101 ($50,000) “Financial Aid, Debt Management, and Socioeconomic Outcomes” 2011-2016 IES Center for the Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment (CAPSEE) ($10,000,000; PI: Thomas Bailey, my projects ~ $760,000 of total) 2012-2013 AERA Research -

Hbcus and the Washington Monthly's College Rankings

Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington Monthly’s College Rankings UNCF Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute Institute for Capacity Building ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was a collaboration between UNCF’s Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute, Drs. Janet Awokoya and David Richards, and UNCF’s Institute for Capacity Building, Dr. Clarissa Myrick-Harris. We are also very grateful to Drs. Karl Reid and Brian Bridges for their editorial comments and advice. Suggested Citation: Awokoya, J., Richards, D., & Myrick-Harris, C. (2012). Serving students and the public good: HBCUs and the Washington Monthly’s College Rankings. Fairfax, VA: Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute, UNCF. Executive Summary Many HBCUs have graduation rates that match and exceed those of many non-HBCUs. Other HBCUs have lower rates, sometimes substantially lower. Such For many, the US News & World Report college comparisons can be misleading, however, because rankings are the gold standard for identifying the they do not take into account the socio-economic country’s best institutions of higher learning. But a backgrounds of the students that colleges serve. Since close analysis of the less well-publicized but highly their founding well over a century ago, HBCUs have respected college rankings compiled by the Washington been dedicated to serving students from low-income Monthly indicates that those rankings may be a better families and those whose pre-college education guide to identifying colleges and universities that has put them at a disadvantage in doing college address one of the nation’s most urgent education coursework. and economic priorities: helping students from low- income, minority families who are often the first in Forty-six percent of HBCU students, for example, their family to attend college—in other words, students come from families with incomes lower than $36,000. -

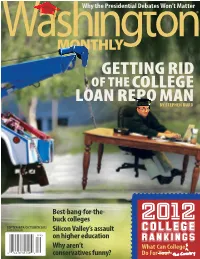

Getting Rid of Thecollege Loan Repo Man by STEPHEN Burd

Why the Presidential Debates Won’t Matter GETTING RID OF THECOLLEGE LOAN REPO MAN BY STEPHEN BURd Best-bang-for-the- buck colleges 2012 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 $5.95 U.S./$6.95 CAN Silicon Valley’s assault COLLEGE on higher education RANKINGS Why aren’t What Can College conservatives funny? Do For You? HBCUsHow do tend UNCF-member to outperform HBCUsexpectations stack in up successfully against other graduating students from disadvantaged backgrounds. higher education institutions in this ranking system? They do very well. In fact, some lead the pack. Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington Monthly’s College Rankings UNCF “Historically black and single-gender colleges continue to rank Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute Institute for Capacity Building well by our measures, as they have in years past.” —Washington Monthly Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington “When it comes to moving low-income, first-generation, minority Monthly’s College Rankings students to and through college, HBCUs excel.” • An analysis of HBCU performance —UNCF, Serving Students and the Public Good based on the College Rankings of Washington Monthly • A publication of the UNCF Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute To receive a free copy, e-mail UNCF-WashingtonMonthlyReport@ UNCF.org. MH WashMonthly Ad 8/3/11 4:38 AM Page 1 Define YOURSELF. MOREHOUSE COLLEGE • Named the No. 1 liberal arts college in the nation by Washington Monthly’s 2010 College Guide OFFICE OF ADMISSIONS • Named one of 45 Best Buy Schools for 2011 by 830 WESTVIEW DRIVE, S.W. The Fiske Guide to Colleges ATLANTA, GA 30314 • Named one of the nation’s most grueling colleges in 2010 (404) 681-2800 by The Huffington Post www.morehouse.edu • Named the No. -

The Impact of Ranking Systems on Higher Education and Its Stakeholders

Journal of Institutional Research 13(1), 83–96. 83 The Impact of Ranking Systems on Higher Education and its Stakeholders MARIAN THAKUR Monash University, Australia Submitted to the Journal of Institutional Research, July 23, 2007, accepted August 27, 2007. Abstract The arrival of university ranking has changed the landscape of higher education all over the world and is likely to continue to influence further development nationally and internationally. This article provides an overview of rankings systems in which Australian universities feature and it goes on further to discuss the impact ranking systems have on higher education and its stakeholders. It concludes by acknowledging that ranking systems are viewed differently by different stakeholders and hence affect them in different ways. While no one ranking can be accepted as definitive, these ranking systems will remain a part of the higher education system for some time to come. Keywords: University rankings; league tables; higher education; stakeholders There is a new era in higher education, characterised by global competition, in which university ranking systems have assumed an importance. Their emergence, often controversial and subject to considerable debate, has been met with a lot of scepticism, some enthusiasm and an institutional unease. Regardless, ranking systems are here to stay and it is important to assess their effect on the higher education sector and its stakeholders. Correspondence to: Marian Thakur, University Planning and Statistics, Monash University, Victoria 3800, Australia. Email: [email protected] Journal of Institutional Research 13(1), 83–96. 84 Overview of ranking systems There are many standards used to assess excellence in universities but the quality of teaching and research is fundamental (Taylor & Braddock, n.d.). -

In the Rankings U.S

in the Rankings U.S. News & World Report UCLA performs very well in all the national and Rank University Score international rankings of the “best” public and private 1 Private Harvard University 100 1 Private Princeton University 100 universities, including the most widely known list 3 Private Yale University 98 published by U.S. News & World Report. 4 Private Columbia University 94 Following is an overview of some of the more significant and well-known national 5 Private California Institute of Technology 93 5 Private Massachusetts Institute of Technology 93 and international rankings. It includes information on UCLA’s standing, as well as commentary that provides a sense of the factors used to determine the rankings. 5 Private Stanford University 93 The charts provide a snapshot of UCLA’s standing in these rankings vis-à-vis other 5 Private University of Chicago 93 top-tier research universities, both public and private. 5 Private University of Pennsylvania 93 10 Private Duke University 92 11 Private Dartmouth College 91 12 Private Northwestern University 90 U.S. News & World Report 13 Private Johns Hopkins University 89 14 Private Washington University in St. Louis 88 USN&WR this year ranked UCLA second among 15 Private Brown University 87 public universities and tied for 25th among all 15 Private Cornell University 87 universities. In all, five University of California 17 Private Rice University 84 campuses ranked among the top 10 public universities in the nation: Berkeley (1st), UCLA 17 Private Vanderbilt University 84 (2nd, tied with University of Virginia), San Diego 19 Private University of Notre Dame 83 (8th), Davis (9th) and Santa Barbara (10th). -

Let Us Rank Journalism Programs Joseph Weber University of Nebraska–Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, College of Journalism & Mass Journalism and Mass Communications, College of Communications 2014 Let Us Rank Journalism Programs Joseph Weber University of Nebraska–Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismfacpub Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Weber, Joseph, "Let Us Rank Journalism Programs" (2014). Faculty Publications, College of Journalism & Mass Communications. 80. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismfacpub/80 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and Mass Communications, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, College of Journalism & Mass Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 69:1 (2014), pp. 76– 86; doi: 10.1177/1077695813517889 Copyright © AEJMC 2013; published by Sage Publications. Used by permission. digitalcommons.unl.edu Online at http://jmce.sagepub.com Essay Let Us Rank Journalism Programs Joseph Weber 307 Andersen Hall, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, 68588-0474 USA; email [email protected] Abstract Unlike law, business, and medical schools, as well as universities in general, jour- nalism schools and journalism programs have rarely been ranked. Publishers such as U.S. News & World Report, Forbes, Bloomberg Businessweek, and Washington Monthly do not pay them much mind. What is the best journalism school in the country? The top ten undergraduate and graduate schools? It is impossible to know. That should change, and the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) should lead the way. -

In the Rankings

IN THE RANKINGS UCLA performs very well in all the national and international U.S. NEWS & WORLD REPORT 23 rankings of the “best” public and private universities, RANK UNIVERSITY SCORE 1 Private Princeton University 100 including the most widely known list published by 2 Private Harvard University 99 U.S. News & World Report. 3 Private Yale University 97 4 Private Columbia University 95 4 Private Stanford University 95 Following is an overview of some of the more significant and well-known national and 4 Private University of Chicago 95 international rankings. It includes information on UCLA’s standing, as well as commentary 7 Private Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) 93 that provides a sense of the factors used to determine the rankings. The charts provide a 8 Private Duke University 92 snapshot of UCLA’s standing in these rankings vis-à-vis other top-tier research universities, 8 Private University of Pennsylvania 91 both public and private. 10 Private California Institute of Technology 90 10 Private Johns Hopkins University 90 12 Private Dartmouth College 89 U.S. News & 12 Private Northwestern University 89 14 Private Brown University 85 World Report 15 Private Cornell University 84 15 Private Vanderbilt University 84 Again this year, UCLA ranked second among 15 Private Washington University in St. Louis 84 public universities, tied for 23rd among all 18 Private Rice University 82 universities in the USN&WR Best Colleges 18 Private University of Notre Dame 82 rankings. Five University of California campuses 20 Public University of California, Berkeley 77 rank in the top 10 among publics: Berkeley (1st), 21 Private Emory University 76 UCLA (2nd), Santa Barbara (8th), Irvine and San Diego (tied for 9th).