E9.3. Updated ISAP for the European Roller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coracias Garrulus

Coracias garrulus -- Linnaeus, 1758 ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- CORACIIFORMES -- CORACIIDAE Common names: European Roller; Roller; Rollier d'Europe European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) In Europe this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). Despite the fact that the population trend appears to be decreasing, the decline is not believed to be sufficiently rapid to approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in Europe. Within the EU27 this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend is not known, but the population is not believed to be decreasing sufficiently rapidly to approach the thresholds under the population -

4. Serbia Bieiii

BIRD PROTECTION AND STUDY SOCIETY OF SERBIA PROVINCIAL SECRETARIAT FOR URBAN PLANNING, CONSTRUCTION AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION SERBIA BIRDS POPULATION AND DISTRIBUTION CURRENT STATUS AND CHALLENGES Slobodan PUZOVI Ć & Milan RUŽI Ć Barcelona, March 2013 CORINE LAND COVER SERBIA 2006 - Monitorning of changes of land use, 1990, 2000. и 2006 - Corine Land Cover 2000 and 2006 database, in relation to Corine Land Cover 1990 database Forests in Serbia 2009 BIRDS IN SERBIA 2009 - c. 360 species - Forest in Serbia - 240 breeding species 2.252.400 ha (30,6%) - Forest ground over 35 % Nonpasseriformes: c.125 Passeriformes: c.115 Protected areas in Serbia 2010 - 5,9% of serbian territory - 465 protected natural areas FOREST HABITAT WATER HABITAT (105.131 hа; 1,4% of Serbia) (2.252.400 ha, 30,6% Србије ) 22) Reeds (c. 2.500 hа, Vojvodina) 1) Lowland aluvian forest (c. 36.000 ha) 23) Water steams (creek, river) (79.247 hа, 1% of Serbia)(beech, 2) Lowland ouk foret (c. 60.000 ha) sand, gravel 1.383 hа) 3) Hilly-mountain ouk forest (720.000 ha, 500-1300m) 24) Water bodies (stagnant water, lake, fish-pond, acumulation) 4) Hllly-mountain beech forest (500-2000m)(661.000 ha) (24.000 hа, 0,3% of Serbia) 5) Spruce foret (c. 50.000 ha, 700 мнв и више ) 25) Main canal network (ДТД sistem, 600 km in Vojvodina) 6) Pine foret (c. 35.000 ha) 26) Supporting canal network (20.100 km in Vojvodina) 7) Pine cvulture (86.000 ha) 8) Spruce culture (c. 35.000 ha, 600 мнв and more) 9) Mixed beech-fir-spruce forest (21.000 ha) AGRICULTURE LAND (5.036.000 ha, 63,7% Србије ) 10) Poplar plantation (37.000 ha) 27) Arable land I (arable land, farmland, large arable 11) ШИКАРЕ И ШИБЉАЦИ (510.000 ha) monoculture,...)(3.600.000 hа) 28) Arable land II (arable land, less parcels, edge bushes, rare ОPEN GLASSLAND HABITAT trees, canals, ...)(1.436.000 hа) 12) Mountain grassland and pasture (above 1000m) 13) Hilly grassland and pasture (400-1000m) URBAN-RURAL PLACES AND BUILDING LAND 14) Lowland pasture (35-400 м, 166.000 ha) (4.681 settlements in Serbia; c. -

Coracias Garrulus, European Roller

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T22682860A131911904 Scope: Global Language: English Coracias garrulus, European Roller Assessment by: BirdLife International View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: BirdLife International. 2018. Coracias garrulus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22682860A131911904. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018- 2.RLTS.T22682860A131911904.en Copyright: © 2018 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Aves Coraciiformes Coraciidae Taxon Name: Coracias garrulus Linnaeus, 1758 Regional Assessments: • Europe Common Name(s): • English: European Roller, Roller • French: Rollier d'Europe Taxonomic Source(s): Cramp, S. -

CBD First National Report

FIRST NATIONAL REPORT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA TO THE UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY July 2010 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................... 3 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 4 2. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Geographic Profile .......................................................................................... 5 2.2 Climate Profile ...................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Population Profile ................................................................................................. 7 2.4 Economic Profile .................................................................................................. 7 3 THE BIODIVERSITY OF SERBIA .............................................................................. 8 3.1 Overview......................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Ecosystem and Habitat Diversity .................................................................... 8 3.3 Species Diversity ............................................................................................ 9 3.4 Genetic Diversity ............................................................................................. 9 3.5 Protected Areas .............................................................................................10 -

European Red List of Birds

European Red List of Birds Compiled by BirdLife International Published by the European Commission. opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Commission or BirdLife International concerning the legal status of any country, Citation: Publications of the European Communities. Design and layout by: Imre Sebestyén jr. / UNITgraphics.com Printed by: Pannónia Nyomda Picture credits on cover page: Fratercula arctica to continue into the future. © Ondrej Pelánek All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder (see individual captions for details). Photographs should not be reproduced or used in other contexts without written permission from the copyright holder. Available from: to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed Published by the European Commission. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. ISBN: 978-92-79-47450-7 DOI: 10.2779/975810 © European Union, 2015 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Printed in Hungary. European Red List of Birds Consortium iii Table of contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................................1 Executive summary ...................................................................................................................................................5 1. -

Phylogeography of the Eurasian Green Woodpecker (Picus Viridis)

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2011) 38, 311–325 ORIGINAL Phylogeography of the Eurasian green ARTICLE woodpecker (Picus viridis) J.-M. Pons1,2*, G. Olioso3, C. Cruaud4 and J. Fuchs5,6 1UMR7205 ‘Origine, Structure et Evolution de ABSTRACT la Biodiversite´’, De´partement Syste´matique et Aim In this paper we investigate the evolutionary history of the Eurasian green Evolution, Muse´um National d’Histoire Naturelle, 55 rue Buffon, C.P. 51, 75005 Paris, woodpecker (Picus viridis) using molecular markers. We specifically focus on the France, 2Service Commun de Syste´matique respective roles of Pleistocene climatic oscillations and geographical barriers in Mole´culaire, IFR CNRS 101, Muse´um shaping the current population genetics within this species. In addition, we National d’Histoire Naturelle, 43 rue Cuvier, discuss the validity of current species and subspecies limits. 3 75005 Paris, France, 190 rue de l’industrie, Location Western Palaearctic: Europe to western Russia, and Africa north of the 4 11210 Port la Nouvelle, France, Genoscope, Sahara. Centre National de Se´quenc¸age, 2 rue Gaston Cre´mieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry Cedex, France, Methods We sequenced two mitochondrial genes and five nuclear introns for 17 5DST/NRF Centre of Excellence at the Percy Eurasian green woodpeckers. Multilocus phylogenetic analyses were conducted FitzPatrick Institute, University of Cape Town, using maximum likelihood and Bayesian algorithms. In addition, we sequenced a Rondebosch 7701, Cape Town, South Africa, fragment of the cytochrome b gene (cyt b, 427 bp) and of the Z-linked BRM 6Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and intron 15 for 113 and 85 individuals, respectively. The latter data set was analysed Department of Integrative Biology, 3101 Valley using population genetic methods. -

PCB Contaminated Site Investigation Report Including

UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Output 5.1 and 5.2 – PCB contaminated site investigation report including investment interest information with the Prioritized list of PCB contaminated site for decontamination related to Full-sized Project to Implement an Environmentally Sound Management and Final Disposal of PCBs in the Republic of Serbia, 100313 5th April 2018 These report provide PCB contaminated site investigation report including investment interest information with the Prioritized list of PCB contaminated site for decontamination to undertake the project activities of the project entitled “Full-sized Project to Implement an Environmentally Sound Management and Final Disposal of PCBs in the Republic of Serbia”, UNIDO ID: 100313, GEF ID: 4877. Introductory considerations Legislative framework Soil protection, as well as soil recovery and remediation are principally regulated by the Law on Environmental Protection (“Official Gazette of the RS” No 135/04, 36/09, 36/09 other law, 72/09 other law), leaving to the special law on soil protection to address the issue in details. The Law on Land Protection ("Sl. glasnik RS", No. 112/15) was adopted by the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia and came into force in January 7, 2016. This law regulates land protection, systematic monitoring of the condition and quality of land, measures for recovery, remediation, recultivation, inspection supervision and other important issues for the protection and conservation of land as a natural resource of national interest. In the transitional Decree of the Law on Protection of Land, it is defined that the by-laws enacted on the basis of the authorization referred to in this Law, shall be adopted within one year from the date of Page 1 of 39 entry into force of this Law. -

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

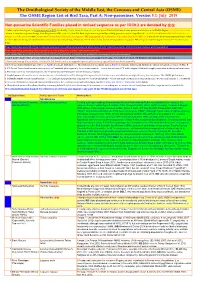

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Conservation Ecology of the European Roller

Conservation ecology of the European Roller Thomas M. Finch A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences University of East Anglia, UK November 2016 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract Among temperate birds, two traits in particular are associated with current population declines; an association with farmed habitats, and the strategy of long-distance migration. The European Roller Coracias garrulus enjoys both of these characteristics, and has declined substantially over the last few decades. Here, I investigate intra- specific variation in Roller breeding ecology and migration in an attempt to work towards conservation solutions. I first compare the breeding ecology of Rollers from two populations; one in Latvia at the northern range limit, and one in France in the core Mediterranean range. I show that the French population is limited principally by nest-site availability, whilst foraging habitat is more important in Latvia. I also highlight the lower productivity of Latvian birds, which also varies substantially from year to year. Comparison of insect and chick feather δ13C and δ15N in France provides little support for specific foraging habitat preferences, providing further evidence that foraging habitat is not limiting for the French population. Next, I provide the most comprehensive analysis of Roller migration to date, showing that Rollers from seven European countries generally occupy overlapping winter quarters. -

Cyclotourism and Campsites in Vojvodina

Tourism Organisation of FREE COPY Vojvodina CYCLOTOURISM AND CAMPSITES IN VOJVODINA www.vojvodinaonline.com SERBIA 2 Državna granica | State Border | Staatsgrenze Pokrajinska granica | Provincial Border | Provinzgrenze Granični prelaz | Border Crossing | Grenzübergang Budapest Magistralni put | Motorway | Landstraße H Tisza Auto-put | Highway | Autobahn Budapest Szeged Priključak na auto-put | A Slip Road | Autobahn anschluss Elevacija | Elevation | Elevation 7 8 P E < 100m 100-200m Subotica Palić Kanjiža Novi Kneževac O 3 R Aranca U 200-400m > 400m Budapest B Duna E Krivaja Čoka Hidrograja | Hydrography | Hydrographie B Reka | River | Fluss E-75 Senta Kanal | Canal | Kanal Kikinda Zlatica S Dunav Bačka Topola Timişoara R Jezero, ribnjak | Lake, shpond | See, teich Ada B 6 Sombor Tisa Čik I 5 Kanal DTD Mali Iđoš J Osijek RO Sedišta opština (broj stanovnika) 12 Bega A A A Nova Crnja Municipality Seat (Population) 11 Apatin M Sitz der Gemeinde (Bevölkerung) a li K a Kula n < 20 000 a Bečej l N.Bečej 20 000 - 50 000 9 Vrbas Begej 50 000 - 100 000 Č Srbobran Tisa Osijek > 100 000 Odžaci Jegrička Timiş HR Žitište Temerin Žabalj N Danube Bač Bački Petrovac K Zrenjanin Sečanj Timişoara Bačka Palanka NOVI SAD A Tisa Donau Kanal DTD Plandište Begej CYCLING ROUTES Sr.Karlovci Beočin Titel A MTB 10 niinnee main route F pla The Danube Route r u Kovačica ke š k a g o čk alternative route Šid r a Vršac aa šš MTB S Opovo rr Irig Alibunar V main route V The Tisa Route Inđija Zagreb E-70 R alternative route Ruma Del Bosut Tamiš ib la T main route Sr.Mitrovica -

Serbia for the Period 2011 – 2018

MINISTRY OF ENVIRONmeNT AND SPATIAL PLANNING BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY OF THE RePUBLIC OF SeRBIA FOR THE PERIOD 2011 – 2018 Belgrade, 2011. IMPRINT Title of the publication: Biodiversity Strategy of the Republic of Serbia for the period 2011 – 2018 Publisher: Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning, Belgrade For Publisher: Oliver Dulic, MD Editors: Prof. Ivica Radovic, PhD Milena Kozomara, MA Photography: Boris Erg, Sergej Ivanov and Predrag Mirkovic Design: Coba&associates Printed on Recycled paper in “PUBLIKUM”, Belgrade February 2011 200 copies ISBN 978-86-87159-04-4 FOR EWORD “Because of the items that satisfy his fleeting greed, he destroys large plants that protect the soil everywhere, quickly leading to the infertility of the soil he inhabits and causing springs to dry up, removing animals that relied on this nature for their food and resulting in large areas of the once very fertile earth that were largely inhabited in every respect, being now barren, infertile, uninhabitable, deserted. One could say that he is destined, after making the earth uninhabitable, to destroy himself” Jean Baptiste Lamarck (Zoological Philosophy, 1809). Two centuries after Lamarck recorded these thoughts, it is as if we were only a step away from fulfilling his alarming prophecy. Today, unfortunately, it is possible to state that man’s influence over the environment has never been as intensive, extensive or far-reaching. The explosive, exponential growth of the world’s population, coupled with a rapid depletion of natural resources and incessant accumulation of various pollutants, provides a dramatic warning of the severity of the situation at the beginning of the third millennium.