Cane and Pilimathalawa Brass Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project for Formulation of Greater Kandy Urban Plan (Gkup)

Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development Urban Development Authority Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN (GKUP) Final Report Volume 2: Main Text September 2018 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. NIKKEN SEKKEI Research Institute EI ALMEC Corporation JR 18-095 Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development Urban Development Authority Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN (GKUP) Final Report Volume 2: Main Text September 2018 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. NIKKEN SEKKEI Research Institute ALMEC Corporation Currency Exchange Rate September 2018 LKR 1 : 0.69 Yen USD 1 : 111.40 Yen USD 1 : 160.83 LKR Map of Greater Kandy Area Map of Centre Area of Kandy City THE PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN (GKUP) Final Report Volume 2: Main Text Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PART 1: INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background .............................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Objective and Outputs of the Project ....................................................... 1-2 1.3 Project Area ............................................................................................. 1-3 1.4 Implementation Organization Structure ................................................... -

District Secretariat—Kandy for the Year 2015

කාය සාධන හා 燒귔 ලාතාල - 2015 nrayhw;Wif kw;Wk; fzf;F mwpf;if Annual Performance & Accounts Report pKfk; khtl;l nrayhsupd; nra;jp 04 Nehf;F 06 nraw;gzpf; $w;W 07 epUthf khtl;l tiug;glk 08 nghJ tpguq;fs; 09 khfhz epu;thfk; 17-39 gapw;rp 뷒ස්ත්රික් ල කමකkw;Wk; කායාය - මහ엔ලර mgptpUj;jp khtl;l nrayfk; - fz;b epiwNtw;wg;gl;l District SecretariattpNrl mk;rq;fs; - Kandy gpuNjr nrayhsu;; fl;bl tpguk; fk neFk tpNrl fUj;jpl;lk; CONTENTS Page Serial Number Description Number Message of District Secretary/ Government Agent, Kandy 1 Introduction of District Secretariat Kandy 1 1.1 Vision, Values and Mission 2 1.2 Quality Policy 3 1.3 Main Duties Performed by the District Secretariat 4-5 2 Kandy District Introduction 6-10 2.1 Administration Map 11 2.2 Basic Information 12 3 Organizational Chart 13 3.1 Approved Carder of Kandy District Secretariat 14 3.2 Approved Carder of Divisional Secretariats 15 4 Performance of District Secretariat 4.1 General Administration 4.1.1 Establishment Division’s Activities 16-19 4.1.2 Activities of the District Media Unit 20 4.1.3 Internal Audit Activities 21-23 4.1.4 District Disaster Management Activities 24-25 4.1.5 Training and Human Resources Development Activities 4.1.5.1 Training Programs 26-27 4.1.5.2 Human Resources and Career Guidance Activities 28-30 4.1.5.3 Productivity Programs 31-32 5 Statutory Activities and other Duties 5.1 Activities of Registration of Persons Department 32-33 5.2 Registrar General Department's Activities 33-34 5.3 District Election Activities 34 5.4 Motor Traffic Unit’s Activities 35 -

Invitation to Bid Ceylon Electricity Board

INVITATION TO BID CEYLON ELECTRICITY BOARD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Region / Bid No. / Item Description & Quantity Bid closing Procurement Place of Purchase of Value of Bid Bond Bids should be Bids will be opened Type Division / date & Time Committee Bidding Documents Price of the (Rs) deposited at at Price of the of Bid Informatio Province TP. Nos. Bid information ICB/ n Copy Document copy NCB Download (Rs) (Rs) Link Materials Generation MC/VIC /OP/2019/16 20/01/2020 Mahaweli DGM (Mahaweli Rs. 3500/= Rs.150,000/- DGM (Mahaweli Complex) DGM (Mahaweli N.A ICB Click here Deputy General (Wednesday) Complex Complex) 40/20, Ampitiya Road, Complex) Manager Supply of 220VDC Battery Chargers for Victoria Power Station. At 10.00 a.m. Procurement 40/20, Ampitiya Road, All payment Kandy. 40/20, Ampitiya Road, (Mahaweli Committee Kandy. shall be made Kandy. Complex) Tel: . +94 81 4953839 at any branch +94 81 2224568 of People’s Fax: .+94 81 2232802 bank to the credit of generation division collection account at People’s bank Dematagoda branch 071- 1001-2-3320- 705 & produce the bank slip Generation/ Extension of Bid Closing Office of Deputy General LKR.45,000.0 LKR. 4,500,000.00 Office of Deputy General The Auditorium, 2nd - ICB Click here Deputy General 23/12/2020 Ministry Manager (Mahaweli 0 (Additional Manager (Corporate Floor, Generation Manager MC/VIC /OP/2020/06 (Wednesday) Procurement Complex), No.40/20, copies may be Affairs), Generation Head Head Quarters, (Mahaweli at 10.00 hrs. Committee Ampitiya Road, purchased up Quarters, Ceylon Ceylon Electricity Complex) SUPPLY OF FOUR (04) NOS. -

Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka

Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka Nirekha De Silva Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka Copyright© WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama, New Delhi, India, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama Core 4A, UGF, India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110 003, India This initiative was made possible by a grant from the Ford Foundation. The views expressed are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of WISCOMP or the Foundation for Universal Responsibility of HH The Dalai Lama, nor are they endorsed by them. 2 Contents Acknowledgements 5 Preface 7 Introduction 9 Methodology 11 List of Abbreviations 13 Civil War in Sri Lanka 14 Army Women 20 LTTE Women 34 Peace and the process of Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration 45 Human Needs and Human Rights in Reintegration 55 Psychological Barriers in Reintegration 68 Social Adjustment to Civil Life 81 Available Mechanisms 87 Recommendations 96 Directory of Available Resources 100 • Counselling Centres 100 • Foreign Recruitment 102 • Local Recruitment 132 • Vocational Training 133 • Financial Resources 160 • Non-Government Organizations (NGO’s) 163 Bibliography 199 List of People Interviewed 204 3 4 Acknowledgements I am grateful to Dr. Meenakshi Gopinath and Sumona DasGupta of Women in Security, Conflict Management and Peace (WISCOMP), India, for offering the Scholar for Peace Fellowship in 2005. -

Viability of Controlled Environmental Agriculture for Vegetable Farmers in Sri Lanka

Viability of Controlled Environmental Agriculture for Vegetable Farmers in Sri Lanka Sharmini K. Kumara Renuka Weerakkody S. Epasinghe Research Report No: 179 January 2015 Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training Institute 114, Wijerama Mawatha Colombo 7 Sri Lanka 1 First Published: January 2015 © 2015, Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training Institute Final typesetting and lay-out by: Dilanthi Hewavitharana Coverpage Designed by: Udeni Karunaratne ISBN: 978-955-612-178-0 II FOREWORD Faced with the limitations of agricultural land, decreasing crop production, climate change and declining biodiversity, and ever increasing population which has led to quadrupling demand for food, protected agriculture has offered a new dimension to produce more in a limited area. Presently a number of tropical countries, including Sri Lanka, has faced a multitude of constraints which has affected crop production in open fields. Main among them are the unpredictable rainfall distribution patterns, causing severe crop failures and yield losses affecting both consumers and the producers who suffer the twin evils of seasonality in production and price fluctuations. Introduced to Sri Lanka in 1987 protected agriculture has gradually gained a foothold in today’s agricultural system. Protected agriculture has a potential for expansion as is associated with large profits, quality products and produce availability at all times of the year. This study provides a detailed description of protected agriculture in Sri Lanka in which crops are grown under different types of protective covers such as the polytunnel, rain shelter and net houses. The report discusses the socio-demographic features of the three different types of operators, crops grown, scale of operation, harvesting, packaging, marketing of vegetables and costs and returns for the profitable crops grown in these structures. -

Registered Repairer in 2020 Colombo District

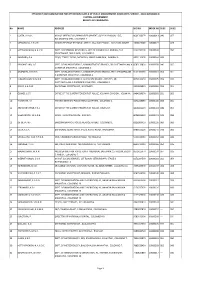

Registered Repairer in 2020 Colombo District - 2020 No Name Technical Name Address Category Digital Technical 1 P.k.K.A.S.M.Kumara P.k.K.A.S.M.Kumara System,No.129/1,Tenna Electronic Scales Watta,Wellampitiya No.43/25,Sanjayapura,Waddya Rd, 2 W.A.P.Chinthaka W.A.P.Chinthaka Dehiwala Electronic Scales WAY Lanka Weighting WAY Lanka Weighting 3 dM.D.J.J.Disanayaka (pvt)Ltd,No.78/1,Main Electronic Scales (ovt)Lt Street,Baththaramulla 4 D.S.S.Kumara D.S.S.Kumara No.78/B,Pagoda Rd,Nugegoda Electronic Scales Fashion Holding (pvt) 5 Fashion Holding (pvt) ltd A.A.R.Sanjeewa ltd,No.22/3,Kanadawaththa Rd, Electronic Scales Palawaththa Rd,Baththaramulla No.461/B/195, City of life, 6 W.M.B.Nalin Kumara W.M.B.Nalin Kumara Electronic Scales Kahatuduwa, Polgasowitha 7 B.N.Boralugoda B.N.Boralugoda No.599, Jayannthi Road, Athurugiriya Electronic Scales No 124/1,Suhada Mawatha,Hokandara 8 G.V.Arjuna Perera G.V.Arjuna Perera Electronic Scales Rd,Hokandara. No.1/3 A,3rd Lane,Gangara 9 V.T.Kodithuwakku V.T.Kodithuwakku Electronic Scales Road,Wewala,Piliyandala No.471,Highlevel Road, Wijerama, 10 N.G.Amal Kumarasena N.G.Amal Kumarasena Electronic Scales Nugegoda No.341/2, 13 B, Mahayayawaths, 11 R.M.T.N.Abeysingha R.M.T.N.Abeysingha Electronic Scales Siddamulla, Gorakapitiya,Piliyandala Ceylon Weighing Mechines Ltd,No.40, 12 S.G.Vithana S.G.Vithana Electronic Scales Maligawa Road,Eathulkotte Ceylon Weighing Machines Ltd, No.40, 13 K.T.L.Senavirathna K.T.L.Senavirathna Electronic Scales Maligawa Road, Ethulkotte Ceylon Weighing Mechines 14 R.A.C.Priyashantha R.A.C.Priyashantha Ltd,No.160,Bauddhalooka Electronic Scales Mawath,Colombo 05 No.276/9C,Athurugiraya 15 B.G.D.D.Perera B.G.D.D.Perera Electronic Scales Mawatha,Himbutana No: 17 Baththaramulla Road,Ethual 16 W.M International W.P.Raj Kumar Electronics Scales Kotte. -

Lions Club of Kandy Hill Capital

Lions Club of Kandy Hill Capital Club No: 099172 Chartered on 20.04.2007 Region : 06 Zone : 01 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Extended By Lions Club of Extension Chairman – Guiding Lion – District Governor then in Office – Club Executives PRESIDENT Lion Ariyadasa Bodaragama M/No. 2653230 No.280, George E De Silva Mw, Kandy. Deputy Commissioner of Excise – Excise Head Office, No. 26, Staple Street, Colombo 02. Tel: 077-7809128(M),081-2225670(R),011-2300171 Email: [email protected] L/L: Anoma SECRETARY Lion Laxman Wijesuriya M/No. 2653240 No. 118, Galkaduwa Rd, Anniwatta, Kandy. Director – Isuru Finance Ltd – Kandy Tel: 071-4731389/077-3593052(M),081-2201550(R) Email: [email protected] L/L: Sumithra TREASURER Lion Chaminda Kuruppuarachchi M/No. 3497024 No. 194, Colombo Rd, Peradeniya. Tel: 071-7252364(M) Email: [email protected] District Cabinet Executives From Lions Club Of Kandy Hill Capital D.G’S PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRPERSON- Micro Finance for Self Employment , Region 06 Lion Eng. M.Ranatunga M/No. 2653232 No. 30/14, Bangalawatta, Lewella, Kandy. Chief Engineer (Electrical) - C.E.B. Kandy. Tel: 071-4215507(M),081-2240999(R),081-2386450(O),081-2223539(F) Email: [email protected] L/L: Dr. Lakmali REGIONAL “GLT” LEADER – Region 06 Lion Dr. Ashoka Dangolla M/No. 2653237 No. 2AB, Upper Hanthana Quarters, University of Peradeniya. Senior Lecture – Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Peradeniya. Tel: 077-7810591/071-8047701(M),081-5675114(R),081-2388664(O),081-2389136(F) Email: [email protected] L/L: Aloma Club Members - 23 Lion Ariyadasa Bodaragama M/No. 2653230 No.280, George E De Silva Mw, Kandy. -

Annual Report of the University of Peradeniya for the Year 2018

The Annual Report of the University of Peradeniya provides a summary of institutional overview of the University's achievements. This is prepared following the standard format prescribed by the Ministry of City Planning, Water Supply and Higher Education. The information contained here is submitted by the respective Faculties, Departments, Centres and Units and complied by the Statistics & Information Division. Compiler: Ms. A.A.K.U. Atapattu Statistical Officer University of Peradeniya English Editor: Ms. Subhagya Liyanage Department of English Faculty of Arts ISSN No: 2478-1088 Vision Be a centre of excellence in higher education with national and international standing. Mission To contribute to society at national and international levels by facilitating, empowering and producing high quality diverse graduates through a conducive learning environment to lead the nation and the world for generation, dissemination and utilization of knowledge through innovative education, multidisciplinary scholarly research linked with industrial and community partnerships. University of Peradeniya Sri Lanka Message from the Vice-Chancellor It brings me great pleasure to present the Annual Report of the University of Peradeniya for the year 2018. This report highlights the successes of the nine Faculties in relation to academic as well as non-academic activities. Furthermore, the achievements of our Centres and Units and their affiliations with other Universities and outside organizations are also presented. The year 2018 has brought many achievements to the University. Some of these noteworthy achievements only a few out of many - are summarized below: - Received seventy-five (75) research grants from reputed, independent research institutions to the value of Rs. 129.64 million. -

EB PMAS Class 2 2011 2.Pdf

EFFICIENCY BAR EXAMINATION FOR OFFICERS IN CLASS II OF PUBLIC MANAGEMENT ASSISTANT'S SERVICE - 2011(II)2013(2014) CENTRAL GOVERNMENT RESULTS OF CANDIDATES No NAME ADDRESS NIC NO INDEX NO SUB1 SUB2 1 COSTA, K.A.G.C. M/Y OF DEFENCE & URBAN DEVELOPMENT, SUPPLY DIVISION, 15/5, 860170337V 10000013 040 057 BALADAKSHA MW, COLOMBO 3. 2 MEDAGODA, G.R.U.K. INLAND REVENUE REGIONAL OFFICE, 334, GALLE ROAD, KALUTARA SOUTH. 745802338V 10000027 --- 024 3 HETTIARACHCHI, H.A.S.W. DEPT. OF EXTERNAL RESOURCES, M/Y OF FINANCE & PLANNING, THE 823273010V 10000030 --- 050 SECRETARIAT, 3RD FLOOR, COLOMBO 1. 4 BANDARA, P.A. 230/4, TEMPLE ROAD, BATAPOLA, MADELGAMUWA, GAMPAHA. 682113260V 10000044 ABS --- 5 PRASANTHIKA, L.G. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATIVE BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM A 858513383V 10000058 040 055 GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 6 ATAPATTU, D.M.D.S. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATION BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM 816130069V 10000061 054 051 A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 7 KUMARIHAMI, W.M.S.N. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ACCOUNTS BRANCH, POB 515, SRI 867010025V 10000075 059 070 CHITTAMPALAM A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 8 JENAT, A.A.D.M. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, NEGOMBO. 685060892V 10000089 034 051 9 GOMES, J.S.T. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA DIVISION, KELANIYA. 846453857V 10000092 031 052 10 HARSHANI, A.I. FINANCE BRANCH, POLICE HEAD QUARTERS, COLOMBO 1. 827122858V 10000104 064 061 11 ABHAYARATHNE, Y.P.J. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA. 841800117V 10000118 049 057 12 WEERAKOON, W.A.D.B. 140/B, THANAYAM PLACE, INGIRIYA. 802893329V 10000121 049 068 13 DE SILVA, W.I. -

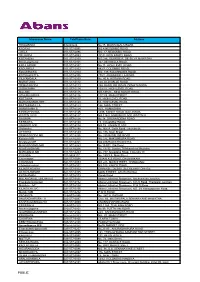

PUBLIC Dehiattakandiya M/B 027-577-6253 NO

Showroom Name TelePhone Num Address HINGURANA 632240228 No.15, MUWANGALA ROAD. KADANA 011-577-6095 NO.4 NEGOMBO ROAD JAELA 011-577-6096 NO. 17, NEGOMBO ROAD DELGODA 011-577-6099 351/F, NEW KANDY ROAD KOTAHENA 011-577-6100 NO:286, GEORGE R. DE SILVA MAWATHA Boralesgamuwa 011-577-6101 227, DEHIWALA ROAD, KIRULAPONE 011-577-6102 No 11, HIGH LEVEL ROAD, KADUWELA 011-577-6103 482/7, COLOMBO ROAD, KOLONNAWA 011-577-6104 NO. 139, KOLONNAWA ROAD, KOTIKAWATTA 011-577-6105 275/2, AVISSAWELLA ROAD, PILIYANDALA 011-577-6109 No. 40 A, HORANA ROAD , MORATUWA 011-577-6112 120, OLD GALLE ROAD, DEMATAGODA 011-577-6113 394, BASELINE ROAD, DEMATAGODA, GODAGAMA 011-577-6114 159/2/1, HIGH LEVEL ROAD. MALABE 011-577-6115 NO.837/2C , NEW KANDY ROAD, ATHURUGIRIYA 011-577-6116 117/1/5, MAIN STREET, KOTTAWA 011-577-6117 91, HIGH LEVEL ROAD, MAHARAGAMA RET 011-577-6120 63, HIGH LEVEL ROAD, BATTARAMULLA 011-577-6123 146, MAIN STREET, HOMAGAMA B 011-577-6124 42/1, HOMAGAMA KIRIBATHGODA 011-577-6125 140B, KANDY ROAD, DALUGAMA, WATTALAJVC 011-577-6127 NO.114/A,GAMUNU PLACE,WATTALA RAGAMA 011-577-6128 No.18, SIRIWARDENA ROAD KESBAWA 011-577-6130 19, COLOMBO ROAD, UNION PLACE 011-577-6134 NO 19 , UNION PLACE Wellwatha 011-577-6148 No. 506 A, Galle Road, colombo 06 ATTIDIYA 011-577-6149 No. 186, Main Street, DEMATAGODA MB 011-577-6255 No. 255 BASELINE ROAD Kottawa M/B 011-577-6260 NO.375, MAKUMBURA ROAD, Moratuwa M/B 011-577-6261 NO.486,RAWATHAWATTA MAHARAGAMA M/B 011-577-6263 No:153/01, Old Road, NUGEGODA MB 011-577-6266 No. -

Chapter 6 Sectoral Situational Analysis

THE PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN Final Report: Vol.2 Main Text CHAPTER 6 SECTORAL SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS 6.1 Transport 6.1.1 General Transport, specifically traffic congestion, is one of the major urban issues in Kandy. There are many factors that aggravate traffic congestion, including (i) the concentration of public facilities in the city centre which generates much traffic, (ii) a limited road network in the mountainous area, (iii) traffic congestion in the town centre mixed with through-traffic on the trunk roads to Kandy and daily traffic inside the city, (iv) traffic bottlenecks at bridges, (v) limited areas designated for parking in the city, and (vi) inappropriate traffic management. Various organisations such as Road Development Authority, Kandy Municipality Council, and Strategic Cities Development Project have conducted studies and implemented projects for the transport sector until recently. In this section, past and present transport plans and projects will be reviewed, and based on lessons learned and experiences, the transport sector’s development orientation that will be in conjunction with regional and city levels will be proposed. 6.1.2 Travel Behaviour in the Heritage Area, Kandy Based on the results of the interview survey, travel behaviour of 2,000 households in the Heritage Area is analysed, and this includes trip purpose, traffic distribution, and travel modes. (1) Trip Purpose The survey results show that the trip purpose of the largest share of respondents is commuting to place of work and business (66%). Meanwhile, some respondents commute to do shopping (14%), go to school (7%), and conduct or attend to business (7%). -

Some Historical Sites in Sri Lanka – Short Notes Jayaindra Fernando

Some historical sites in Sri Lanka – short notes Jayaindra Fernando Introduction Sri Lanka is a land like no other, with multitude of places to see. If you are over 18 and has not seen these places, then there is no time to lose. If you have children under 18 still there is no time to lose. Show them these cultural gems before they leave the nest to roam the wide geographical and social world on their own. Your country deserves the duty and your Lankan born children are entitled to the privilege. This document is a rough note and not a publication. Distances are as of the original writings and not converted to metric. Of course it is incomplete. All information in this are already in the public domain. Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Anuradhapura and surrounding area ................................................................................................. 3 Sri maha bodi ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Brazen palace ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Ruvanweliseya .................................................................................................................................... 3 Jethawana ..........................................................................................................................................