A Case Study of the Little Big Horn College Mission by Nathaniel Rick St Pierre a Thesis Submit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educating the Mind and Spirit 2006-2007

Educating the Mind and Spirit 2006-2007 ANNUAL REPORT ENVISIONING OUR POWERFUL FUTURE MISSION The American Indian College Fund’s mission is to raise scholarship funds for American Indian students at qualified tribal colleges and universities and to generate broad awareness of those institutions and the Fund itself. The organization also raises money and resources for other needs at the schools, including capital projects, operations, endowments or program initiatives, and it will conduct fundraising and related activities for any other Board- directed initiatives. CONTENTS President’s Message 2 Chairman’s Message 3 Tribal Colleges and Students by State 4 The Role of Tribal Colleges and Universities 5 Scholarship Statistics 6 Our Student Community 7 Scholarships 8 Individual Giving 9 Corporations, Foundations, and Tribes 10 Special Events and Tours 12 Student Blanket Contest 14 Public Education 15 Corporate, Foundation, and Tribal Contributors 16 Event Sponsors 17 Individual Contributors 18 Circle of Vision 19 Board of Trustees 20 American Indian College Fund Staff 21 Independent Auditor’s Report 22 Statement of Financial Position 23 Statement of Activities 24 Statement of Cash Flows 25 Notes to Financial Statement 26 Schedule of Functional Expenses 31 1 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The Circle of Life, the Circle of Hope Dear Friends and Relatives, ast year I wrote about the challenges that faced Gabriel plans to graduate with a general studies the nation and how hope helps us endure those degree from Stone Child College, then transfer to the L -

Hermann NAEHRING: Wlodzimierz NAHORNY: NAIMA: Mari

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Hermann NAEHRING: "Großstadtkinder" Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Stefan Dohanetz -d; Henry Osterloh -tymp; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24817 SCHLAGZEILEN 6.37 Amiga 856138 Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Stefan Dohanetz -d; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24818 SOUJA 7.02 --- Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Volker Schlott -fl; recorded 1985 in Berlin A) Orangenflip B) Pink-Punk Frosch ist krank C) Crash 24819 GROSSSTADTKINDER ((Orangenflip / Pink-Punk, Frosch ist krank / Crash)) 11.34 --- Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24820 PHRYGIA 7.35 --- 24821 RIMBANA 4.05 --- 24822 CLIFFORD 2.53 --- ------------------------------------------ Wlodzimierz NAHORNY: "Heart" Wlodzimierz Nahorny -as,p; Jacek Ostaszewski -b; Sergiusz Perkowski -d; recorded November 1967 in Warsaw 34847 BALLAD OF TWO HEARTS 2.45 Muza XL-0452 34848 A MONTH OF GOODWILL 7.03 --- 34849 MUNIAK'S HEART 5.48 --- 34850 LEAKS 4.30 --- 34851 AT THE CASHIER 4.55 --- 34852 IT DEPENDS FOR WHOM 4.57 --- 34853 A PEDANT'S LETTER 5.00 --- 34854 ON A HIGH PEAK -

OUR COMMUNITY IS OUR STRENGTH EDUCATION IS the ANSWER OUR MISSION and Communities

2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT OUR COMMUNITY IS OUR STRENGTH OUR MISSION The American Indian College Fund invests in Native students and tribal college education to transform lives and communities. EDUCATION IS THE ANSWER EDUCATION TABLE OF CONTENTS How Your Donations Are Used: Fulfilling Our Mission . 2 Our Impact 2019-20 . 3 Message from the President . 4 Where Our Scholars Study . 6 Meeting Challenges in the Wake of the Pandemic . 8 Rx for Healthy Communities: Investing in Education . 10–15 California Tribe Invests in State’s Future Leaders . 16 Native Representation in Arts and Student Success Are Woven Together into Partnership with Pendleton Woolen Mills . 18 American Indian College Fund Supporters . 20 2019-20 Governing Board of Trustees . 23 Audited Financial Information . 24 1 HOW YOUR DONATIONS ARE USED: FULFILLING OUR MISSION Scholarships, Programs, and Administration Fundraising Public Education 72.08%* 4.55%* 23.37%* OUR COMMITMENT TO YOU For more than 30 years, the American Indian College Fund has been committed to transparency and accountability while serving our students, tribal colleges, and communities. We consistently receive top ratings from independent charity evaluators. EDUCATION IS THE ANSWER EDUCATION • We earned the “Best in America Seal of Excellence” from the Independent Charities of America. Of the one million charities operating in the United States, fewer than 2,000 organizations have been awarded this seal. • The College Fund meets the Standards for Charity Accountability of the Better Business Bureau’s Wise Giving Alliance. • The College Fund received a Gold Seal of Transparency from Guidestar. • The College Fund consistently receives high ratings from Charity Navigator. -

Tcus As Engaged Institutions

Building Strong Communities Tribal Colleges as Engaged Institutions Prepared by: American Indian Higher Education Consortium & The Institute for Higher Education Policy A product of the Tribal College Research and Database Initiative Building Strong Communities: Tribal Colleges as Engaged Institutions APRIL 2001 American Indian Higher Education Consortium The Institute for Higher Education Policy A product of the Tribal College Research and Database Initiative, a collaborative effort between the American Indian Higher Education Consortium and the American Indian College Fund ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is the fourth in a series of policy reports produced through the Tribal College Research and Database Initiative. The Initiative is supported in part by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Native Ameri- cans (ANA) and the Pew Charitable Trusts. A collaborative effort between the American Indian Higher Education Consor- tium (AIHEC) and the American Indian College Fund, the project is a multi-year effort to improve understanding of Tribal Colleges. AIHEC would also like to thank the W.K. Kellogg Foundation for its continued support. This report was prepared by Alisa Federico Cunningham, Senior Research Analyst, and Christina Redmond, Research Assis- tant, at The Institute for Higher Education Policy. Jamie Merisotis, President, Colleen O’Brien, Vice President, and Deanna High, Project Editor, at The Institute, as well as Veronica Gonzales, Jeff Hamley, and Sara Pena at AIHEC, provided writing and editorial assistance. We also would like to acknowledge the individuals and organizations who offered information, advice, and feedback for the report. In particular, we would like to thank the many Tribal College presidents who read earlier drafts of the report and offered essential feedback and information. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

For Indigenous Students

For Indigenous Students SAY EDUCATION GUIDE 2018 | 21 SAY Magazine Survey Tips on how to use our Education Guide This Guide features over three hundred institutions, which includes You will find some information on Aboriginal/Native American some new listings and some updates from last year’s Guide. specific programs, services and courses offered by that particular institution. Use the legend below which explains the different types We want to thank those institutions who were very generous of symbols used in the grid. in sharing this information for your benefit. Some institutions were unable to respond to our request for information. If your For further information and a full description of the programs/ institution needs to be added, or has new/updated information, services these institutions offer, you should always review the insti- this can be done at http://saymag.com/2018-education-guide- tution’s website. You will discover more information that the SAY native-people-survey/. Scroll down the home page to ‘SAY 2018 Guide does not provide. Education Directory Form’. Although SAY Magazine has made every attempt to ensure The material in the grid comes from counsellors dealing with material in the Guide is correct, this is not a comprehensive listing Indigenous students. We asked them what information is most and SAY Magazine is not responsible for any errors or omissions. requested by Indigenous students and those are the questions asked in the survey sent to education institutions. This will give you a better understanding of the types of schools Electronic copies of back issues from 2009-2017 and the featured in the Guide, making it easier to find a good fit for you. -

CHAIR, AIHEC B July 29, 2020 Chairman Hoeven, Vice-Chairman Udall, and Members of the Committee, on Behalf of My Institution, Li

STATEMENT OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN HIGHER EDUCATION CONSORTIUM DR. DAVID YARLOTT CHAIR, AIHEC BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRESIDENT, LITTLE BIG HORN COLLEGE– CROW AGENCY, MONTANA U.S. SENATE - COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS HEARING ON SAFELY REOPENING BUREAU OF INDIAN EDUCATION SCHOOLS July 29, 2020 Chairman Hoeven, Vice-Chairman Udall, and members of the Committee, on behalf of my institution, Little Big Horn College in Crow Agency, Montana and the 36 other Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs) that collectively are the American Indian Higher Education Consortium (AIHEC), thank you for inviting me to testify on the efforts of TCUs to safely remain open in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. My name is Baluxx Xiassash -- Outstanding Singer. I am a member of the Uuwuutasshe Clan and a child of the Uuwuutasshe Clan of the Apsáalooke or Crow Indians. The Crow reservation is located in what is now south-central Montana and contains about 3000 square miles – a territory larger than the state of Rhode Island. In the early 1980s, my tribe established Little Big Horn College, forging a new tradition in education to grow an Apsáalooke workforce that would rebuild and sustain our tribal families, communities, and lands. The goal was to establish a lasting tradition of advanced training and higher education, for a good path into the future for the Crow People. I am proud to say that I am a product of my tribe’s commitment to higher education: I attended Little Big Horn College as a student (returning years later to earn a degree); I served on the faculty of Little Big Horn College; and after earning advanced degrees, I became an administrator at the college. -

Powell Woman Placed on Probation for Burglary Spree

THURSDAY, MARCH 28, 2019 109TH YEAR/ISSUE 25 Powell woman placed on NEW CITY ADMINISTRATOR probation for burglary spree BY CJ BAKER program last year persuaded are violations of the terms and Overfield instead suspended Tribune Editor District Court Judge Bobbi conditions of this probation, eight to 10 years of prison time, Overfield to give the … the state most which the judge could impose if Powell woman has been defendant an oppor- likely won’t hesitate Lamb-Harlan makes a misstep sentenced to three years tunity to prove that to bring you back on probation. Aof supervised probation she’s changed. before this court — During the two years that for committing a string of bur- “I can pretty much and most likely, this her cases were pending in Park glaries in 2017, while on proba- guarantee you with court won’t hesitate County’s court system, Lamb- tion for a meth-related offense. this sentence that to impose a sentence Harlan served roughly a year Prosecutors and Valorie you’re going to be accordingly.” and two months in jail. Lamb-Harlan’s probation under some pret- Deputy Park She tearfully apologized for agent had recommended that ty strict scrutiny County Prosecuting her actions at Friday’s hearing. the 45-year-old be sent to for the next three Attorney Leda Po- “I know I have been, like, out prison. But Lamb-Harlan’s years,” Overfield jman argued for of control because of drugs and apparent turnaround after she warned Lamb-Har- VALORIE a nine- to 10-year completed a drug treatment lan. -

Tourisme Outaouais

OFFICIAL TOURIST GUIDE 2018-2019 Outaouais LES CHEMINS D’EAU THE OUTAOUAIS’ TOURIST ROUTE Follow the canoeist on the blue signs! You will learn the history of the Great River and the founding people who adopted it. Reach the heart of the Outaouais with its Chemins d’eau. Mansfield-et-Pontefract > Mont-Tremblant La Pêche (Wakefield) Montebello Montréal > Gatineau Ottawa > cheminsdeau.ca contents 24 6 Travel Tools regional overview 155 Map 8 Can't-miss Experiences 18 Profile of the Region 58 top things to do 42 Regional Events 48 Culture & Heritage 64 Nature & Outdoor Activities 88 Winter Fun 96 Hunting & Fishing 101 Additional Activities 97 112 Regional Flavours accommodation and places to eat 121 Places to Eat 131 Accommodation 139 useful informations 146 General Information 148 Travelling in Quebec 150 Index 153 Legend of Symbols regional overview 155 Map TRAVEL TOOLS 8 Can't-miss Experiences 18 Profile of the Region Bring the Outaouais with you! 20 Gatineau 21 Ottawa 22 Petite-Nation La Lièvre 26 Vallée-de-la-Gatineau 30 Pontiac 34 Collines-de-l’Outaouais Visit our website suggestions for tours organized by theme and activity, and also discover our blog and other social media. 11 Website: outaouaistourism.com This guide and the enclosed pamphlets can also be downloaded in PDF from our website. Hard copies of the various brochures are also available in accredited tourism Welcome Centres in the Outaouais region (see p. 146). 14 16 Share your memories Get live updates @outaouaistourism from Outaouais! using our hashtag #OutaouaisFun @outaouais -

A Cheyenne Odyssey”

Mission 3: “A Cheyenne Odyssey” COMPLETE CLASSROOM GUIDE TEACHER’S GUIDE Table of Contents Overview Content Advisory .......................................................................................................................................... 5 About Mission 3: “A Cheyenne Odyssey” ........................................................................................ .......... 7 Mission 3 At A Glance ............................................................................................................................... 11 Essential Questions ..................................................................................................................................... 14 Models of Instruction .................................................................................................................................. 15 Learning Goals ............................................................................................................................................ 20 National Standards Alignment ................................................................................................................... 23 Background Timeline of Events Before, During, and After the Mission ........................................................................ 28 Educator’s Primer on the Historical Period ................................................................................................ 33 Glossary of Key Terms ............................................................................................................................... -

Pathways to Excellence Strategic Plan, 1992

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 358 858 IR 054 583 TITLE Pathways to Excellence: A Report on Improving Library and Information Services for Native American Peoples. INSTITUTION National Commission on Libraries and Information Science, Washington, D. C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-16-038158-4 PUB DATE Dec 92 NOTE 585p. AVAILABLE FROMU.S. Government Printing Office, Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF03/PC24 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Culture; *American Indian History; *American Indians; Evaluation Methods; Financial Support; GoVernment Role; Improvement; *Information Services; Information Technology; Library Collections; Library Cooperation; *Library Planning; Literacy Education; *Long Range Planning; Museums; Records Management; Technical Assistance IDENTIFIERS National Commission Libraries Info_mation Science; Native Americans; Service Delivery Assessment; Service Quality ABSTRACT The U.S. National Commission on Libraries and Information Science began in early 1989 to study library and information services for Native American peoples. This report is the culmination of the evaluation, which included site visits ano field hearings. The largely undocumented knowledge base of Native American experience must be recorded and preserved if it is not to be lost. Ten major challenges were identified on topics such as funding support, training and technical assistance, tribal library holdings, cooperative activities, state and local partnerships, federal policy, model programs, museum and archival services, adult and family literacy programs, and newer information technology. The report contains detailed descriptions of Commission activities and incorporates a "Summary Report" (also published separately), as well as the "Long Range Action Plan" containing strategies for high quality information services to Native American peoples. -

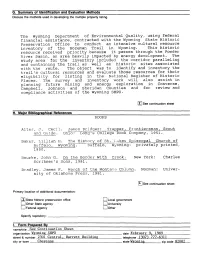

The Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality, Using

G. Summary of identification and Evaluation Methods Discuss the methods used in developing the multiple property listing. The Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality, using federal financial assistance, contracted with the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office to conduct an intensive cultural resource inventory of the Bozeman Trail in Wyoming. This historic resource received priority because it passes through the Powder River Basin, an area heavily impacted by energy development. The study area for the inventory included the corridor paralleling and containing the trail as well as historic sites associated with the route. The object was to identify and inventory the trail's cultural resources and evaluate those resources for their eligibility for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. The survey and inventory work will also assist in planning future mining and energy exploration in Converse, Campbell, Johnson and Sheridan Counties and for review and compliance activities of the Wyoming SHPO. |X I See continuation sheet H. Major Bibliographical References BOOKS Alter, J. Cecil. James Bridger: Trapper, Frontiersman, Scout and Guide. Ohio": Long's College Book Company, 1951. Baker, Lillian H. The History of St. Lukes Episcopal Church of Buffalo, Wyoming. Buffalo, Wyoming: privately printed, 1950. Bourke, John G. On the Border With Crook. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1981. Bradley, James F. March of the Montana Column. Norman: Univer sity of Oklahoma Press, 1981. See continuation sheet Primary location of additional documentation: H State historic preservation office I I Local government EH Other State agency dl University I I Federal agency D Other Specify repository: ___________ I. Form Prepared By name/title See Continuation Sheet organization Wyoming SHPO date February 9, 1989 street & number 2301 Central, Barrett Building telephone (307) 777-6311_____ city or town Cheyenne_________________ state Wyoming______ zip code 82002 F.