Arabic Loanwords in the Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Ankawa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MCC Service Opportunity ______

MCC Service Opportunity ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Assignment Title: Intensive English Program Teacher Term: 5 weeks (June 28 – August 1, 2015) FTE: 1 Location: Ankawa / Erbil, Iraq Start Date: Jun/28/2015 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ All MCC workers are expected to exhibit a commitment to: a personal Christian faith and discipleship; active church membership; and biblical nonviolent peacemaking. MCC is an equal opportunity employer, committed to employment equity. MCC values diversity and invites all qualified candidates to apply. Synopsis: The Chaldean Archdiocese of Erbil has asked MCC to provide a minimum of 3 and not more than 6 English teachers to teach English language skills to teachers, seminarians, nuns and members of the Chaldean community in Ankawa, Iraq. Three English language teachers will have primary responsibility for working together to teach English vocabulary, grammar and reading/listening and speaking/writing skills to Iraqi teachers at Mar Qardakh School. Additional teachers will provide English language instruction to members of the Chaldean community who are not teaching at Mar Qardakh School but who need to improve their English skills. Classes will be held each day, Sunday – Thursday, from 9:00 am – 12:30 PM. The program for students will begin on Sunday, July 5 and end on Thursday, July 30, 2015. Financial arrangements. The partner organization will cover food, lodging, travel to and from the assignment as well as work-related transportation. The short term teacher will cover all other expenses including visa costs, health insurance, medical costs and all personal expenses. Qualifications: 1. All MCC workers are expected to exhibit a commitment to a personal Christian faith and discipleship, active church membership, and nonviolent peacemaking. -

Greek and Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes

GREEK AND LATIN ROOTS, PREFIXES, AND SUFFIXES This is a resource pack that I put together for myself to teach roots, prefixes, and suffixes as part of a separate vocabulary class (short weekly sessions). It is a combination of helpful resources that I have found on the web as well as some tips of my own (such as the simple lesson plan). Lesson Plan Ideas ........................................................................................................... 3 Simple Lesson Plan for Word Study: ........................................................................... 3 Lesson Plan Idea 2 ...................................................................................................... 3 Background Information .................................................................................................. 5 Why Study Word Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes? ......................................................... 6 Latin and Greek Word Elements .............................................................................. 6 Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 6 Root, Prefix, and Suffix Lists ........................................................................................... 8 List 1: MEGA root list ................................................................................................... 9 List 2: Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 32 List 3: Prefix List ...................................................................................................... -

Possible Historical Traces in the Doctrina Addai

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, Vol. 9.1, 51-127 © 2006 [2009] by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute and Gorgias Press POSSIBLE HISTORICAL TRACES IN THE DOCTRINA ADDAI ILARIA L. E. RAMELLI CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF THE SACRED HEART, MILAN 1 ABSTRACT The Teaching of Addai is a Syriac document convincingly dated by some scholars in the fourth or fifth century AD. I agree with this dating, but I think that there may be some points containing possible historical traces that go back even to the first century AD, such as the letters exchanged by king Abgar and Tiberius. Some elements in them point to the real historical context of the reign of Abgar ‘the Black’ in the first century. The author of the Doctrina might have known the tradition of some historical letters written by Abgar and Tiberius. [1] Recent scholarship often dates the Doctrina Addai, or Teaching of Addai,2 to the fourth century AD or the early fifth, a date already 1 This is a revised version of a paper delivered at the SBL International Meeting, Groningen, July 26 2004, Ancient Near East section: I wish to thank very much all those who discussed it and so helped to improve it, including the referees of the journal. 2 Extant in mss of the fifth-sixth cent. AD: Brit. Mus. 935 Add. 14654 and 936 Add. 14644. Ed. W. Cureton, Ancient Syriac Documents (London 1864; Piscataway: Gorgias, 2004 repr.), 5-23; another ms. of the sixth cent. was edited by G. Phillips, The Doctrine of Addai, the Apostle (London, 1876); G. -

Types and Functions of Reduplication in Palembang

Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society JSEALS 12.1 (2019): 113-142 ISSN: 1836-6821, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52447 University of Hawaiʼi Press TYPES AND FUNCTIONS OF REDUPLICATION IN PALEMBANG Mardheya Alsamadani & Samar Taibah Wayne State University [email protected] & [email protected] Abstract In this paper, we study the morphosemantic aspects of reduplication in Palembang (also known as Musi). In Palembang, both content and function words undergo reduplication, generating a wide variety of semantic functions, such as pluralization, iteration, distribution, and nominalization. Productive reduplication includes full reduplication and reduplication plus affixation, while fossilized reduplication includes partial reduplication and rhyming reduplication. We employed the Distributed Morphology theory (DM) (Halle and Marantz 1993, 1994) to account for these different patterns of reduplication. Moreover, we compared the functions of Palembang reduplication to those of Malay and Indonesian reduplication. Some instances of function word reduplication in Palembang were not found in these languages, such as reduplication of question words and reduplication of negators. In addition, Palembang partial reduplication is fossilized, with only a few examples collected. In contrast, Malay partial reduplication is productive and utilized to create new words, especially words borrowed from English (Ahmad 2005). Keywords: Reduplication, affixation, Palembang/Musi, morphosemantics ISO 639-3 codes: mui 1 Introduction This paper has three purposes. The first is to document the reduplication patterns found in Palembang based on the data collected from three Palembang native speakers. Second, we aim to illustrate some shared features of Palembang reduplication with those found in other Malayic languages such as Indonesian and Malay. The third purpose is to provide a formal analysis of Palembang reduplication based on the Distributed Morphology Theory. -

Iraq - CCCM Camps Status Report As of 19 May 2015

Iraq - CCCM Camps status report As of 19 May 2015 Key information Distribution of IDP Camp in Iraq Dahuk 1 10 1 Diyala 3 3 1 TOTAL Iraqs 239 440 Baghdad 4 2 Ninewa 5 1 Erbil 3 1 Sulaymaniyah 1 2 Kirkuk 2 1 TOTAL KRI Region of Iraq 209 603 Basrah 1 1 Najaf 1 Salah al-Din 1 Wassit 1 Missan 1 TOTAL Centre and South Iraq 29 837 Babylon 1 Kerbala 1 Closed open Under Construction IDPs in Kurdistan Region* of Iraq Current Planned capacity Plots Construction lead / # Governorate District Camp population Camp management Status individuals Available Shelter Care individuals TOTAL KRI Region of Iraq 209 603 232 707 4 288 Dahuk 142 554 151 082 1 522 UNHCR/KURDS/Dohu 1 Dahuk Sumel Bajet Kandala 12 721 12 000 1 522 Dohuk Governorate open k Governorate Dohuk 2 Dahuk Sumel Kabarto 1 14 067 12 000 - Dohuk Governorate governorate/Artosh open company Dohuk 3 Dahuk Sumel Kabarto 2 14 122 - - Dohuk Governorate Governorate/Doban open and Shahan company 4 Dahuk Sumel Khanke 18 165 21 840 - Dohuk Governorate UNHCR/KURDS open 5 Dahuk Sumel Rwanga Community 14 775 16 000 - Dohuk Governorate open 6 Dahuk Sumel Shariya 18 699 28 000 - Dohuk Governorate open AFAD/Dohuk 7 Dahuk Zakho Berseve 1 11 242 15 000 - Dohuk Governorate open Governorate 8 Dahuk Zakho Berseve 2 9 336 10 920 - Dohuk Governorate UNHCR/PWJ open 9 Dahuk Zakho Chamishku 25 318 30 000 - Dohuk Governorate Dohuk Governorate open 10 Dahuk Zakho Darkar - - - UN-Habitat Under Construction HABITAT / IOM / 11 Dahuk Zakho Dawadia 4 109 5 322 - Dohuk Governorate open UNDP 12 Dahuk Zakho Wargahe Zakho - - - -

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE and HERITAGE Basra Its History, Culture and Heritage

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE CULTURE : ITS HISTORY, BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins Edited by Paul Collins BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins © BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ 2019 ISBN 978-0-903472-36-4 Typeset and printed in the United Kingdom by Henry Ling Limited, at the Dorset Press, Dorchester, DT1 1HD CONTENTS Figures...................................................................................................................................v Contributors ........................................................................................................................vii Introduction ELEANOR ROBSON .......................................................................................................1 The Mesopotamian Marshlands (Al-Ahwār) in the Past and Today FRANCO D’AGOSTINO AND LICIA ROMANO ...................................................................7 From Basra to Cambridge and Back NAWRAST SABAH AND KELCY DAVENPORT ..................................................................13 A Reserve of Freedom: Remarks on the Time Visualisation for the Historical Maps ALEXEI JANKOWSKI ...................................................................................................19 The Pallakottas Canal, the Sealand, and Alexander STEPHANIE -

Erbil: 3W Partners Per Health Facility (As of Jan 2018)

IRAQ Erbil: 3W Partners per Health Facility (as of Jan 2018) Turkey Consultations by DISTRICT Jan-Dec 2017 Dahuk 11 Iran Erbil 144,887 Partners in Erbil Mergasur Governorate Makhmur 139,010 Soran Shaqlawa 7,662 Al Mustaqbal Choman Consultations by CAMP Jan-Dec 2017 AMAR DoH Erbil UNICEF Ankawa 2 2,123 Ninewa UPP Shaqlawa WHO Baharka 50,594 Baharka Debaga 1 90,561 Al Mustaqbal Erbil Harshm ZHIAN Ankawa 2 Sulaymaniyah Debaga 2 UNICEF 9,645 IOM Debaga S. 10,652 UPP Erbil Koisnjaq WAHA Harshm 16,744 WHO Makhmur Debaga 2 Debaga Stadium Debaga TC 1,879 Debaga TC Debaga 1 212,382 LEGEND 1,718 IDP Camp IDPs by camp IRAQ IDP Transit Camp Feb 15, 2018 Salah al-Din Disclaimer: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this Kirkuk map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO IDPs by district 820 concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authori- ties, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All reasonable Feb 15, 2018 precautions have been taken by WHO to produce this map. The responsibility for its interpretation and use lies with the user. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. 11,508 292 6,318 6,276 200 4,248 Production Date: 28 Feb 2018 174 Product Name: IRQ_ERBIL_3W_Partners_Per_Health_Facility_28022018 Data source: Health cluster partners Erbil Koisnjaq Makhmur Mergasur Shaqlawa Soran Baharka Debaga 2 Debaga Harsham HEALTH CLUSTER (as of Jan 2018) IRAQ Erbil: 3W Partners per Health -

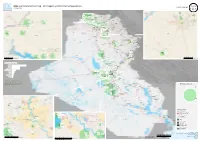

IRAQ: Operational Context Map - IDP Temporary Settlements and Populations UNHCR - IRAQ IMU - 26 Sep 2016

IRAQ: Operational context map - IDP Temporary Settlements and populations UNHCR - IRAQ IMU - 26 Sep 2016 Caspian Sea Caspian Sea Akre Hamdaniya Baharka NINAWA Derkar Bajet Zakho Batifa Harshm TURKEY Zakho Dawadia Kandala Chamishku Berseve 1 Amadiya DOHUK Amedi Sheladize Ankawa 2 Rwanga Mergasur Dahuk Barzan Soran Community Sumel Dahuk Sumel Mergasur Berseve 1 Kabarto 1 Kabarto 2 Akre Chamishku Darkar Berseve 2 Essian Erbil Shariya Qasrok Akre Zakho Zumar Khanke Shikhan Soran Telafar Shikhan Rovia Mamilian Choman Amalla Sheikhan Rawanduz Choman Wargahe Tilkaif Garmawa Mamrashan Harir Zakho Tilkaif Nargizlia Bardarash Bashiqah Bardarash Shaqlawa Zelikan Shaqlawa Mosul Baretle Kawrgosk Pirmam Bahirka (Masif) Hamdaniya Hiran Sinjar Baharka Khushan Rania Pshdar Hamdaniya Harshm Rania Qalat Hamam Aynkawah Chwarqurna Erbil Bakhdida Ankawa 2 diza Rwanga Al Alil Erbil Binaslawa Hajyawa Mosul Mamyzawa Kuna Bajet Community Koisnjaq Ba'Aj Erbil Gork Kandala Koisnjaq NINAWA Debaga ERBIL Dokan Dokan ERBIL Stadium Debaga 1 Surdesh Mawat DOHUK Al Qaiyara Debaga 2 Hamdaniyah Sharbazher Garmik Makhmur Chwarta Dabes Ba'aj Penjwin Dabes Penjwin Hatra Bazyan As Sulaymaniyah Dahuk Chamchamal Shirqat SULAYMANIYAH Arbat Kirkuk Barzinja Barzinja Hatra Kirkuk Sulaymaniya IDP Arbat Seyyed Halabjay Shirqat Taza Laylan Qara Sadeq Hawiga Taza Khurmatu IDP Dagh Ashti Khurmal KIRKUK Sirwan Yahyawa Qadir IDP Biara Sumel Hawiga Qarim Dukaro Daquq Nazrawa Darbandihkan Halabja SYRIAN ARAB Daquq Chamchamal Halabja REPUBLIC Darbandikhan Daquq Dahuk Baiji Tooz Khurmatu Kalar -

Camps Location - As of 18 February 2018

For Humanitarian Purposes Only IRAQ Production date : 18 February 2018 Camps Location - As of 18 February 2018 R I Shikhan Essian Ain Sifne TURKEY Telafar Sheikhan Darkar Zakho Garmawa Mamrashan Chamishku Bersive II Nargizlia Piran (new) Akre 1 + 2 Zakho Bersive I Dahuk Zelikan New Qaymawa (former Rwanga Amedi Piran Zelikan) Community (Nargizlia 3) Bajed Kandala Dahuk Tilkaif Bardarash Sumel Amedi Erbil Sumel Kabarto Akre Mergasur Hamdaniya II Dahuk Hasansham M2 Kabarto I Shariya Bartella Khanke Shikhan Soran Telafar Akre Mergasur Mosul Hasansham U3 Gawilan Domiz I+II Akre Lower Ain Sifne Khazer M1 Mamilian Soran Choman Hamdaniya Hasansham U2 Amalla Chamakor Tilkaif As Salamiyah Choman Mosul Hamam 1 -3 Tilkaif Shaqlawa Basirma Al Alil 1 As Salamiyah Darashakran - 2 Nimrud Telafar Hamdaniya Erbil Sinjar Sinjar Mosul Kawergosk Shaqlawa Rania Baharka Hamdaniya Pshdar Harshm Ranya Ankawa 2 Erbil Ninewa Qalat Dizah Mosul Koysinjaq Erbil Dokan Ba'aj Qushtapa Koisnjaq Debaga 1 Debaga 3 Dokan Debaga 2 Debaga Stadium Qayyarah-Jad'ah Makhmur 1-6 Surdesh Sharbazher Ba'aj Haj Ali Penjwin Qayyarah-Airstrip Dabes Kirkuk Sulaymaniyah Chwarta Penjwin Makhmur Sulaymaniyah Hatra Basateen Al Dabes Barzinja Sheuokh Kirkuk Shirqat Chamchamal Hatra Laylan 2 Arbat IDP Ashti IDP Shirqat Laylan Nazrawa IDP Arbat Hawiga Yahyawa Sulaymaniyah Halabja Laylan 3 Refugee Dukaro Daquq Chamchamal Kirkuk Halabja Daquq Darbandikhan Hawiga Darbandikhan Daquq Baiji Hajjaj Camp Baiji Al Alam 1, 2, 3 Kalar Al Sh'hamah Tooz Tal al-Seebat Salah Adhamia Al Safyh Ru'ua Tazade al-Din -

Sister Nazek Matty About Her Return in Iraq

Sister Nazek Matty about her return in Iraq: Sometimes we find it difficult to share our unusual experiences, simply because we have no words to describe them. In these few lines, I will try to share the most unusual experience I have ever lived in my life. In so doing I am taking this opportunity to extend my thanks to those kind people who helped me grow in many ways. I finished my doctorate programme in February 2014. The title of my thesis was: Historical Reconstruction of Sennacherib’s Campaign against Judah and Jerusalem in 701. I returned to my country, Iraq, in March 2014. I was so grateful to the Lord that he put on my path extremely kind and generous people who helped me study and achieve my ambition to be a biblical researcher. When I arrived in Iraq, I was really happy to be reunited with my Dominican Sisters and my family. The conditions were not settled, yet I was hoping, like other Iraqi Christians, that they would improve. In few weeks I was asked to teach Introduction to the New Testament at a Catholic Centre in Qaraqosh/Nineveh (about 30 km from Mosul); also, I was offered to teach as a lecturer at Babel College (a Catholic college based in Ankawa/Erbil) for the academic year 2014-2015. I was glad that things were going as I had hoped. But summer came in Iraq with wicked winds that disturbed everything and made us all reconsider what we had planned. The ISIS entered Mosul and captured it on the 9th of June, and then we had to face a new reality realizing that our presence in Iraq as Christians was openly and rigorously threatened. -

Abstract Title of Dissertation: NEGOTIATING the PLACE OF

Abstract Title of Dissertation: NEGOTIATING THE PLACE OF ASSYRIANS IN MODERN IRAQ, 1960–1988 Alda Benjamen, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation Directed by: Professor Peter Wien Department of History This dissertation deals with the social, intellectual, cultural, and political history of the Assyrians under changing regimes from the 1960s to the 1980s. It examines the place of Assyrians in relation to a state that was increasing in strength and influence, and locates their interactions within socio-political movements that were generally associated with the Iraqi opposition. It analyzes the ways in which Assyrians contextualized themselves in their society and negotiated for social, cultural, and political rights both from the state and from the movements with which they were affiliated. Assyrians began migrating to urban Iraqi centers in the second half of the twentieth century, and in the process became more integrated into their societies. But their native towns and villages in northern Iraq continued to occupy an important place in their communal identity, while interactions between rural and urban Assyrians were ongoing. Although substantially integrated in Iraqi society, Assyrians continued to retain aspects of the transnational character of their community. Transnational interactions between Iraqi Assyrians and Assyrians in neighboring countries and the diaspora are therefore another important phenomenon examined in this dissertation. Finally, the role of Assyrian women in these movements, and their portrayal by intellectuals, -

Learn-The-Aramaic-Alphabet-Ashuri

Learn The ARAMAIC Alphabet 'Hebrew' Ashuri Script By Ewan MacLeod, B.Sc. Hons, M.Sc. 2 LEARN THE ARAMAIC ALPHABET – 'HEBREW' ASHURI SCRIPT Ewan MacLeod is the creator of the following websites: JesusSpokeAramaic.com JesusSpokeAramaicBook.com BibleManuscriptSociety.com Copyright © Ewan MacLeod, JesusSpokeAramaic.com, 2015. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into, a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, scanning, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without prior written permission from the copyright holder. The right of Ewan MacLeod to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the copyright holder's prior consent, in any form, or binding, or cover, other than that in which it is published, and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Jesus Spoke AramaicTM is a Trademark. 3 Table of Contents Introduction To These Lessons.............................................................5 How Difficult Is Aramaic To Learn?........................................................7 Introduction To The Aramaic Alphabet And Scripts.............................11 How To Write The Aramaic Letters....................................................... 19