Play Redux: the Form of Computer Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flexible Games by Which I Mean Digital Game Systems That Can Accommodate Rule-Changing and Rule-Bending

Let’s Play Our Way: Designing Flexibility into Card Game Systems Gifford Cheung A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: David Hendry, Chair David McDonald Nicolas Ducheneaut Jennifer Turns Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Information School ©Copyright 2013 Gifford Cheung 2 University of Washington Abstract Let’s Play Our Way: Designing Flexibility into Card Game Systems Gifford Cheung Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor David Hendry Information School In this dissertation, I explore the idea of designing “flexible game systems”. A flexible game system allows players (not software designers) to decide on what rules to enforce, who enforces them, and when. I explore this in the context of digital card games and introduce two design strategies for promoting flexibility. The first strategy is “robustness”. When players want to change the rules of a game, a robust system is able to resist extreme breakdowns that the new rule would provoke. The second is “versatility”. A versatile system can accommodate multiple use-scenarios and can support them very well. To investigate these concepts, first, I engage in reflective design inquiry through the design and implementation of Card Board, a highly flexible digital card game system. Second, via a user study of Card Board, I analyze how players negotiate the rules of play, take ownership of the game experience, and communicate in the course of play. Through a thematic and grounded qualitative analysis, I derive rich descriptions of negotiation, play, and communication. I offer contributions that include criteria for flexibility with sub-principles of robustness and versatility, design recommendations for flexible systems, 3 novel dimensions of design for gameplay and communications, and rich description of game play and rule-negotiation over flexible systems. -

Old Japan Redux 3

Old Japan Redux 3 Edited by X. Jie YANG February 2017 The cover painting is a section from 弱竹物語, National Diet Library. Old Japan Redux 3 Edited by X. Jie YANG, February 2017 Content Poem and Stories The Origins of Japan ……………………………………………… April Grace Petrascu 2 Journal of an Unnamed Samurai ………………………………… Myles Kristalovich 5 Holdout at Yoshino ……………………………………………………… Zachary Adrian 8 Memoirs of Ieyasu ……………………………………………………………… Selena Yu 12 Sword Tales ………………………………………………………………… Adam Cohen 15 Comics Creation of Japan …………………………………………………………… Karla Montilla 19 Yoshitsune & Benkei ………………………………………………………… Alicia Phan 34 The Story of Ashikaga Couple, others …………………… Qianhua Chen, Rui Yan 44 This is a collection of poem, stories and manga comics from the final reports submitted to Japanese Civilization, fall 2016. Please enjoy the young creativity and imagination! P a g e | 2 The Origins of Japan The Mythical History April Grace Petrascu At the beginning Izanagi and Izanami descended The universe was chaos Upon these islands The heavens and earth And began to wander them Just existed side by side Separately, the first time Like a yolk inside an egg When they met again, When heaven rose up Izanami called to him: The kami began to form “How lovely to see Four pairs of beings A man such as yourself here!” After two of genesis The first-time speech was ever used. Creating the shape of earth The male god, upset Izanagi, male That the first use of the tongue Izanami, the female Was used carelessly, Kami divided He once again circled the land By their gender, the only In an attempt to cool down Kami pair to be split so Once they met again, Both of these two gods Izanagi called to her: Emerged from heaven wanting “How lovely to see To build their own thing A woman like yourself here!” Upon the surface of earth The first time their love was matched. -

Boris Pasternak - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Boris Pasternak - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Boris Pasternak(10 February 1890 - 30 May 1960) Boris Leonidovich Pasternak was a Russian language poet, novelist, and literary translator. In his native Russia, Pasternak's anthology My Sister Life, is one of the most influential collections ever published in the Russian language. Furthermore, Pasternak's theatrical translations of Goethe, Schiller, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, and William Shakespeare remain deeply popular with Russian audiences. Outside Russia, Pasternak is best known for authoring Doctor Zhivago, a novel which spans the last years of Czarist Russia and the earliest days of the Soviet Union. Banned in the USSR, Doctor Zhivago was smuggled to Milan and published in 1957. Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature the following year, an event which both humiliated and enraged the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In the midst of a massive campaign against him by both the KGB and the Union of Soviet Writers, Pasternak reluctantly agreed to decline the Prize. In his resignation letter to the Nobel Committee, Pasternak stated the reaction of the Soviet State was the only reason for his decision. By the time of his death from lung cancer in 1960, the campaign against Pasternak had severely damaged the international credibility of the U.S.S.R. He remains a major figure in Russian literature to this day. Furthermore, tactics pioneered by Pasternak were later continued, expanded, and refined by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and other Soviet dissidents. <b>Early Life</b> Pasternak was born in Moscow on 10 February, (Gregorian), 1890 (Julian 29 January) into a wealthy Russian Jewish family which had been received into the Russian Orthodox Church. -

Game Design 2 Game Balance

CE810 - Game Design 2 Game Balance Joseph Walton-Rivers & Piers Williams Friday, 18 May 2018 University of Essex 1 What is Balance? Game Balance Question What is balance? 2 Game Balance “All players have an equal chance of winning” – Richard Bartle Richard covered a combat example in the first part of the module. 3 On Strategies Game Balance • What about higher level strategies? • Zerg rush? • Dominant strategies • Metagaming 4 Metagaming - Rock Paper Scissors • A beats B, B beats C, C beats A • If there are lots of A players, people will play C • Then there are a lot of C players, so people play B • and so on... 5 Metagaming - Dominant Strategies • What if A is significantly stronger? • No one will use the other two strategies • We want to encourage variety in play 6 Can we detect this? • Can we detect strategies which are overpowered? • Try to punish strategies we don’t want to see • We did this earlier in the week with rotate and shoot! • Can we measure this? 7 Automated Game Tuning • Academics seem to think so... • Ryan Leigh et al (2008) - Co-evolution for game balancing • Alexander Jaffe et al (2012) - Restricted-Play balance framework • Mihail Morosan - GAs for tuning parameters 8 Game Curves First Move Advantage First Move Advantage • Typically affects turn based games • Going first in tac tac toe means either a win or adraw • White has > 50% win rate over all games • Worse effects if you have resources • We need a way of dealing with this 9 First Move Advantage Magic Second player gets an extra card Go Second player gets 7.5 bonus -

Military Retirement Fund Audited Financial Report

Fiscal Year 2020 Military Retirement Fund Audited Financial Report November 9, 2020 Table of Contents Management’s Discussion and Analysis ..............................................................................................................1 REPORTING ENTITY ....................................................................................................................................... 1 THE FUND ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 General Benefit Information ........................................................................................................................... 2 Non-Disability Retirement from Active Service ............................................................................................ 3 Disability Retirement ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Reserve Retirement ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Survivor Benefits ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA) ............................................................................................ 9 Cost-of-Living Increase ................................................................................................................................. -

2K Announces Sid Meier's Civilization® VI for Nintendo Switch September

2K Announces Sid Meier’s Civilization® VI for Nintendo Switch September 13, 2018 6:46 PM ET The full Civilization VI experience comes to a home console for the first time Join the conversation on Twitter using the hashtag #OneMoreTurn NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Sep. 13, 2018-- 2K and Firaxis Games today announced that Sid Meier’s Civilization® VI, winner of The Game Awards’ Best Strategy Game, DICE Awards’ Best Strategy Game and latest entry in the prestigious Civilization franchise, is coming to Nintendo Switch™ on November 16, 2018. Additionally, 2K and Firaxis Games have partnered with Aspyr Media to bring Civilization VI to Nintendo Switch and ensure the experience meets the same high standards of the beloved series. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home /20180913005109/en/ Originally created by legendary game designer, Sid Meier, Civilization is a turn-based strategy game in which you build an empire to stand the 2K and Firaxis Games today announced that Sid test of time. Explore a new land, research technology, conquer your Meier's Civilization® VI, winner of The Game Awards' Best Strategy Game, DICE Awards' Best enemies, and go head-to-head with history’s most renowned leaders as Strategy Game and latest entry in the prestigious you attempt to build the greatest civilization the world has ever known. Civilization franchise, is coming to Nintendo Switch™ on November 16, 2018. (Graphic: Business Now on Nintendo Switch, the quest to victory in Civilization VI can Wire) take place wherever and whenever players want. -

Rubicite Breastplate, Priced to Move Cheap

Burke, Rubicite Breastplate Rubicite Breastplate Priced to Move, Cheap: How Virtual Economies Become Real Simulations Timothy Burke Department of History Swarthmore College June 2002 Almost everyone was unhappy, the d00dz and the carebears, the role-players and dedicated powergamers, and almost everyone was expressing their anger on websites and bulletin boards. It was patch day in the computer game Asheron’s Call, an eagerly anticipated monthly event, when new content, new events, new tools and tricks, were introduced by the game’s designers. A big nerf had come down from on high. There had been no warning. Nerfing was a way of life over at the other big multiplayer games, but supposedly not in Asheron’s Call. This time, the fabled Greater Shadow armor, the ultimate in personal protection, was now far less desirable than it had been the day before the patch. The rare crystal shards used to forge the armor, which had become an unofficial currency, were greatly reduced in value, while anyone who already possessed the earlier, more powerful version of the armor found themselves far wealthier than they had been the day before. Asheron’s Call was one of three major commercial “persistent world” massively multiplayer computer games available in the spring of 2001, the others being Everquest and Ultima Online. (Since that time, a number of other games in this genre have appeared, with more on the way.) In these games, tens of thousands of players within a shared virtual environment control alternate personas, characters who retain their abilities 1 Burke, Rubicite Breastplate and possessions from session to session and who can acquire additional skills or objects over time. -

Online Media Business Models: Lessons from the Video Game Sector

Komorowski, M and Delaere, S. (2016). Online Media Business Models: Lessons from the Video Game Sector. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 11(1), 103–123, DOI: http://dx.doi. org/10.16997/wpcc.220 RESEARCH ARTICLE Online Media Business Models: Lessons from the Video Game Sector Marlen Komorowski and Simon Delaere imec-SMIT, Vrije Universiteit, Brussels, BE Corresponding author: Marlen Komorowski ([email protected]) Today’s media industry is characterized by disruptive changes and business models have been acknowledged as a driving force for success. Current business model research manages only to grasp static descriptions while in reality media managers are struggling with the dynamics of the industry. This article aims to close this gap by investigating a new paradigm of online media business models. Based on three video game case studies of the massively multiplayer online role-playing game genre, this article explores a novel theoretical approach to explain the changes that can be made within business models. The article highlights the importance of changing processes within online media business models and emphasises that the video game sector is at the forefront of business innovation. Finally, it demonstrates that online media business model change is in a trade-off paradigm between capturing or offering potentially higher value per player vs. accessing a potentially larger player-base. Key words: Media industry; business model; process; disruption; video game sector Introduction Today’s media industry is characterized by disruptive transformations shaped by digitization. Digitization is not only generating new business opportunities but threatens traditional commercialization strategies and is proving highly unpredictable with regards to future market development. -

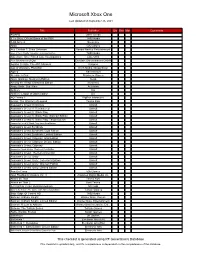

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Section One: Getting Started

Section One: Getting Started As you get started on your journey, you will be faced with a few decisions. Some of these will have minimal impact on your long term play, while others will play an important part in how you experience the game. This section will cover the first of those decisions – server (known as ‘shards’ in UO) selection, character creation, and an explanation of the different clients used to play the game (Classic and Enhanced). In this section we will also cover some of the most basic elements of the game that will be a foundation for understanding your new world. This will include basic movement controls, as well as how to use the overhead radar feature. Choose Your Client – Classic vs. Enhanced We will begin with an explanation of the two clients available for use with Ultima Online – the Classic Client and the Enhanced Client. Your choice of client will greatly affect how you view, and play, the game. The best part about having two different clients is that you are not bound to one or another – you are free to switch back and forth so long as you have both installed on your system. Following is a brief explanation of the differences between the two clients. Later in this section will be pictures illustrating some of the differences between the two clients. Classic Client The Classic Client is the original client used to play Ultima Online. It does not have as many features as the Enhanced Client, but is still preferred by many longtime players who favor its simpler nature and the nostalgia that comes with experiencing the game as it was originally intended. -

Family Friendly Magazine 129 in PDF Format

Family Friendly Gaming The VOICE of TM the FAMILY in GAMING Kingdom Hearts III, Ooblets, Monster Hunter World and more in this fabu- lous issue!! ISSUE #129 NI NO KUNI II REVENANT KING- DOM wants you to April 2018 role play. CONTENTS ISSUE #129 April 2018 CONTENTS Links: Home Page Section Page(s) Editor’s Desk 4 Female Side 5 Comics 7 Sound Off 8 - 10 Look Back 12 Quiz 13 Devotional 14 Helpful Thoughts 15 In The News 16 - 23 We Would Play That! 24 Reviews 25 - 37 Sports 38 - 41 Developing Games 42 - 67 Now Playing 68 - 83 Last Minute Tidbits 84 - 106 “Family Friendly Gaming” is trademarked. Contents of Family Friendly Gaming is the copyright of Paul Bury, and Yolanda Bury with the exception of trademarks and related indicia (example Digital Praise); which are prop- erty of their individual owners. Use of anything in Family Friendly Gaming that Paul and Yolanda Bury claims copyright to is a violation of federal copyright law. Contact the editor at the business address of: Family Friendly Gaming 7910 Autumn Creek Drive Cordova, TN 38018 [email protected] Trademark Notice Nintendo, Sony, Microsoft all have trademarks on their respective machines, and games. The current seal of approval, and boy/girl pics were drawn by Elijah Hughes thanks to a wonderful donation from Tim Emmerich. Peter and Noah are inspiration to their parents. Family Friendly Gaming Page 2 Page 3 Family Friendly Gaming Editor’s Desk FEMALE SIDE this instance I feel wonderful. God has given God is my prize and my goal. -

Origin Systems Article

'Standing, left to right: Ken Arnold, Mike Ward, Laurie Thatcher, James Van Artsdalen, Helen Garriott, John Van Artsdalen Seated: Richard Garriott, Robert Garriott, Chuck Bueche. ORIGIN SYSTEMS As unlikely a pair as Chuck Bueche and Richard Garriott seem to be, novation to the marketplace. the synthesis of their personalities is the fuel for Origin Systems . One of the areas to watch is Garriott's Ultima series, The soul of Chuck Bueche, who prefers the moniker "Chuckles," and Richard Ultima has had four incarnations, beginning with Akalabeth and currently Garriott, better known in Apple circles as Lord British, are the principal existing in Exodus: Ultima III. Despite the apparent one-dimensional players of Origin Systems. Garriott's brother Robert, who likes to be theme, each Ultima seems like a completely different game, since each called "Robert," handles the business end of the company . differs so markedly from the last. The differences between scenarios Anyone familiar with Chuckles and Lord British only through their isn't much by choice, but rather because Garriott keeps finding more works would never picture the two working together. Chuckles is a car- ways to enhance the game by teaching the computer to perform more toon; British is a fantasy hero. Chuckles is Papa Smurf; British is Kull tricks, Eventually, Garriott hopes to develop the ultime Ultima setup the Conqueror. One is cotton candy and ice cream; the other is roast and then develop scenarios using that setup. pheasant and ale, New Company's New Idea. One area of computer games that has Misnomer. Origin Systems can be labeled a newcomer to the com- been explored minimally, if at all, is Steve Jackson microgames.