113 Current Members of Congress As Amici Curiae in Support of Defendants-Appellees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1605026 NY Spotlight Memo

! MEMORANDUM TO: Interested Parties FROM: Alixandria Lapp, Executive Director, House Majority PAC DATE: May 26, 2016 RE: Congressional Democrats Poised for Pick-Ups Across the Empire State With just over a month until New York’s June 28 congressional primaries, and just under six months from the November general election, Democrats are poised for significant pick-ups in congressional districts across the Empire State. This year Democrats are overwhelmingly on offense in New York – with at least six Republican held seats that could be flipped this November. Multiple Republican incumbents and challengers are finding their already-precarious political prospects diminishing even further as they struggle with a damaging party brand, a toxic presidential ticket-mate, and increasingly prove themselves out of touch with their own districts. Bottom line: With New York’s congressional Republicans increasingly vulnerable heading into the fall, Democrats are overwhelmingly on offense and well-positioned to win key districts across the state in 2016. New York Republicans Tied to Toxic Brand As in any presidential year, down-ballot races will be heavily shaped by the top of the ticket. For Republicans, particularly in New York, that’s bad news. Even before the GOP presidential race took shape, New York’s congressional Republicans faced significant structural political challenges. In six competitive Republican-held districts, President Obama either won or came within 1% of winning in 2008 and 2012. Now with Donald Trump as their presidential ticket-mate, down-ballot prospects for New York Republicans are far worse. Earlier this month, a poll by Morning Consult found that nearly half of all Americans would “be less likely to support candidates for public office if they say they back Donald Trump.” And despite Donald Trump’s big win in New York’s presidential primary, there’s no indication that it will translate to success in November. -

Lobbying Contribution Report

8/1/2016 LD203 Contribution Report LOBBYING CONTRIBUTION REPORT Clerk of the House of Representatives • Legislative Resource Center • 135 Cannon Building • Washington, DC 20515 Secretary of the Senate • Office of Public Records • 232 Hart Building • Washington, DC 20510 1. FILER TYPE AND NAME 2. IDENTIFICATION NUMBERS Type: House Registrant ID: Organization Lobbyist 35195 Organization Name: Senate Registrant ID: Honeywell International 57453 3. REPORTING PERIOD 4. CONTACT INFORMATION Year: Contact Name: 2016 Ms.Stacey Bernards MidYear (January 1 June 30) Email: YearEnd (July 1 December 31) [email protected] Amendment Phone: 2026622629 Address: 101 CONSTITUTION AVENUE, NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001 USA 5. POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE NAMES Honeywell International Political Action Committee 6. CONTRIBUTIONS No Contributions #1. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $1,500.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: Friends of Sam Johnson Sam Johnson #2. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $2,500.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: Kay Granger Campaign Fund Kay Granger #3. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $2,000.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: Paul Cook for Congress Paul Cook https://lda.congress.gov/LC/protected/LCWork/2016/MM/57453DOM.xml?1470093694684 1/75 8/1/2016 LD203 Contribution Report #4. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $1,000.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: DelBene for Congress Suzan DelBene #5. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $1,000.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: John Carter for Congress John Carter #6. -

Employees of Northrop Grumman Political Action Committee (ENGPAC) 2017 Contributions

Employees of Northrop Grumman Political Action Committee (ENGPAC) 2017 Contributions Name Candidate Office Total ALABAMA $69,000 American Security PAC Rep. Michael Dennis Rogers (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Byrne for Congress Rep. Bradley Roberts Byrne (R) Congressional District 01 $5,000 BYRNE PAC Rep. Bradley Roberts Byrne (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Defend America PAC Sen. Richard Craig Shelby (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Martha Roby for Congress Rep. Martha Roby (R) Congressional District 02 $10,000 Mike Rogers for Congress Rep. Michael Dennis Rogers (R) Congressional District 03 $6,500 MoBrooksForCongress.Com Rep. Morris Jackson Brooks, Jr. (R) Congressional District 05 $5,000 Reaching for a Brighter America PAC Rep. Robert Brown Aderholt (R) Leadership PAC $2,500 Robert Aderholt for Congress Rep. Robert Brown Aderholt (R) Congressional District 04 $7,500 Strange for Senate Sen. Luther Strange (R) United States Senate $15,000 Terri Sewell for Congress Rep. Terri Andrea Sewell (D) Congressional District 07 $2,500 ALASKA $14,000 Sullivan For US Senate Sen. Daniel Scott Sullivan (R) United States Senate $5,000 Denali Leadership PAC Sen. Lisa Ann Murkowski (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 True North PAC Sen. Daniel Scott Sullivan (R) Leadership PAC $4,000 ARIZONA $29,000 Committee To Re-Elect Trent Franks To Congress Rep. Trent Franks (R) Congressional District 08 $4,500 Country First Political Action Committee Inc. Sen. John Sidney McCain, III (R) Leadership PAC $3,500 (COUNTRY FIRST PAC) Gallego for Arizona Rep. Ruben M. Gallego (D) Congressional District 07 $5,000 McSally for Congress Rep. Martha Elizabeth McSally (R) Congressional District 02 $10,000 Sinema for Arizona Rep. -

Voters: Climate Change Is Real Threat; Want Path to Citizenship for Illegal Aliens; See Themselves As 2Nd Amendment Supporters; Divided on Obamacare & Fed Govt

SIENA RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIENA COLLEGE, LOUDONVILLE, NY www.siena.edu/sri For Immediate Release: Tuesday, September 27, 2016 Contact: Steven Greenberg (518) 469-9858 Crosstabs; website/Twitter: www.Siena.edu/SRI/SNY @SienaResearch Time Warner Cable News / Siena College 19th Congressional District Poll: Game On: Faso 43 Percent, Teachout 42 Percent ¾ of Dems with Teachout, ¾ of Reps with Faso; Inds Divided Voters: Climate Change Is Real Threat; Want Path to Citizenship for Illegal Aliens; See Themselves as 2nd Amendment Supporters; Divided on Obamacare & Fed Govt. Involvement in Economy Trump Leads Clinton by 5 Points; Schumer Over Long by 19 Points Loudonville, NY. The race to replace retiring Republican Representative Chris Gibson is neck and neck, as Republican John Faso has the support of 43 percent of likely voters and Democrat Zephyr Teachout has the support of 42 percent, with 15 percent still undecided, according to a new Time Warner Cable News/Siena College poll of likely 19th C.D. voters released today. Both have identical 75 percent support among voters from their party, with independents virtually evenly divided between the two. By large margins, voters say climate change is a real, significant threat; want a pathway to citizenship for aliens here illegally; and, consider themselves 2nd Amendment supporters rather than gun control supporters. Voters are closely divided on Obamacare, supporting its repeal by a small four-point margin, and whether the federal government should increase or lessen its role to stimulate the economy. In the race for President, Donald Trump has a 43-38 percent lead over Hillary Clinton, while Chuck Schumer has a 55-36 percent lead over Wendy Long in the race for United States Senator. -

Andrew Heaney the Political Landscape NY-19

The Candidate: Andrew Heaney Andrew is a young small business owner recruited by the Party leadership in his county to run for this office, there is wide support and enthusiasm within the party for his candidacy. The number one issue facing the 19th Congressional District is economic growth and job creation. Andrew's success as a small business owner and intimate knowledge of the tax code and regulatory environment make him the best candidate to help grow the local economy. Despite being an outsider Andrew has strong connections to a committed national donor base. Andrew’s father in law, Larry Bathgate, was RNC Finance Chair for both Presidents Reagan and Bush 41. Leslie Heaney has taken a leadership role in the campaign overall, but especially with respect to finance. Beating the Democrat will be expensive. Andrew outraised everybody in NYS - both incumbent and candidates and ranked among the top ten nationally. In the first two filing quarters of his campaign Andrew has outpaced Faso raising over $1million. Choosing to forgo the insider designation process, heavily favoring career politicians like Faso; the Heaney campaign is taking its message directly to the people and is the first campaign on the airwaves throughout the district. The Political landscape NY-19 Like national Republicans, GOP voters in 19th Congressional District are fed up with politicians, all politicians - and want an outsider to change the culture in Washington. The outsider anti-establishment candidacies of Donald Trump and Ted Cruz are strong in New York. A February 8, 2016 Siena Poll shows Donald Trump with34% while Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz each have the support of 16% The Cook Political Report designates the 19th district as one of 12 out of 435 nationally that is designated as a Republican swing district, which means without a great GOP candidate, the Republicans will lose this seat. -

Election 2006

APPENDIX: CANDIDATE PROFILES BY STATE We analyzed the fair trade positions of candidates in each race that the Cook Political Report categorized as in play. In the profiles below, race winners are denoted by a check mark. Winners who are fair traders are highlighted in blue text. Alabama – no competitive races___________________________________________ Alaska_________________________________________________________________ Governor OPEN SEAT – incumbent Frank Murkowski (R) lost in primary and was anti-fair trade. As senator, Murkowski had a 100% anti-fair trade voting record. 9 GOP Sarah Palin’s trade position is unknown. • Democratic challenger Tony Knowles is a fair trader. In 2004, Knowles ran against Lisa Murkowski for Senate and attacked her for voting for NAFTA-style trade deals while in the Senate, and for accepting campaign contributions from companies that off-shore jobs.1 Arizona________________________________________________________________ Senate: Incumbent GOP Sen. Jon Kyl. 9 Kyl is anti-fair trade. Has a 100% anti-fair trade record. • Jim Pederson (D) is a fair trader. Pederson came out attacking Kyl’s bad trade record in closing week of campaign, deciding to make off-shoring the closing issue. On Nov. 3 campaign statement: “Kyl has repeatedly voted for tax breaks for companies that ship jobs overseas, and he has voted against a measure that prohibited outsourcing of work done under federally funded contracts,” said Pederson spokesman Kevin Griffis, who added that Pederson “wants more protections [in trade pacts] related to child labor rules and environmental safeguards to help protect U.S. jobs.”2 House Arizona 1: GOP Rep. Rick Renzi incumbent 9 Renzi is anti-fair trade. 100% bad trade vote record. -

URGENT: Call to Stop Medicaid Cuts!

June 21, 2017 URGENT: Call to Stop Medicaid Cuts! Medicaid funds 90% of NYS supports and services for people with developmental disabilities – including residential and adult day services, respite, community habilitation, certain special education costs, as well as medical services. Medicaid funds are in serious jeopardy: The U.S. House of Representatives already passed their version of the American Health Care Act (AHCA), which would cut Medicaid by $880 BILLION over the next 10 years. The U.S. Senate is poised to pass a similar bill that would cut and cap Medicaid. After the Senate passes its version, it may send it to the House for a vote. We have heard that the secret Senate AHCA version is 80% of the House AHCA bill with additional Medicaid cuts! If the AHCA were enacted, the #bFair2DirectCare funding would be eliminated and some services for people with developmental disabilities would likely be cut back or eliminated altogether. Cuts would worsen the existing crisis in recruiting and retaining direct support staff. Without sufficient staff, people with disabilities would not be safe. NY Senators Schumer and Gillibrand already oppose AHCA, but many of our NYS Representatives support it. We need to explain to these Representatives that Medicaid cuts would be disastrous for people with developmental disabilities. Please Make 7 Quick Calls Immediately! Call the following Representatives. Tell them: My name is _____________ I am the parent/relative/friend of a person with developmental disabilities. I am calling to ask you to oppose any legislation that would cut or cap Medicaid. Medicaid funds 90% of essential services for people with developmental disabilities. -

115Th Congress Roster.Xlsx

State-District 114th Congress 115th Congress 114th Congress Alabama R D AL-01 Bradley Byrne (R) Bradley Byrne (R) 248 187 AL-02 Martha Roby (R) Martha Roby (R) AL-03 Mike Rogers (R) Mike Rogers (R) 115th Congress AL-04 Robert Aderholt (R) Robert Aderholt (R) R D AL-05 Mo Brooks (R) Mo Brooks (R) 239 192 AL-06 Gary Palmer (R) Gary Palmer (R) AL-07 Terri Sewell (D) Terri Sewell (D) Alaska At-Large Don Young (R) Don Young (R) Arizona AZ-01 Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Tom O'Halleran (D) AZ-02 Martha McSally (R) Martha McSally (R) AZ-03 Raúl Grijalva (D) Raúl Grijalva (D) AZ-04 Paul Gosar (R) Paul Gosar (R) AZ-05 Matt Salmon (R) Matt Salmon (R) AZ-06 David Schweikert (R) David Schweikert (R) AZ-07 Ruben Gallego (D) Ruben Gallego (D) AZ-08 Trent Franks (R) Trent Franks (R) AZ-09 Kyrsten Sinema (D) Kyrsten Sinema (D) Arkansas AR-01 Rick Crawford (R) Rick Crawford (R) AR-02 French Hill (R) French Hill (R) AR-03 Steve Womack (R) Steve Womack (R) AR-04 Bruce Westerman (R) Bruce Westerman (R) California CA-01 Doug LaMalfa (R) Doug LaMalfa (R) CA-02 Jared Huffman (D) Jared Huffman (D) CA-03 John Garamendi (D) John Garamendi (D) CA-04 Tom McClintock (R) Tom McClintock (R) CA-05 Mike Thompson (D) Mike Thompson (D) CA-06 Doris Matsui (D) Doris Matsui (D) CA-07 Ami Bera (D) Ami Bera (D) (undecided) CA-08 Paul Cook (R) Paul Cook (R) CA-09 Jerry McNerney (D) Jerry McNerney (D) CA-10 Jeff Denham (R) Jeff Denham (R) CA-11 Mark DeSaulnier (D) Mark DeSaulnier (D) CA-12 Nancy Pelosi (D) Nancy Pelosi (D) CA-13 Barbara Lee (D) Barbara Lee (D) CA-14 Jackie Speier (D) Jackie -

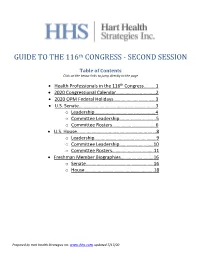

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

WNBC/Marist Poll NYS Campaign 2006

WNBC/Marist Poll Poughkeepsie, NY 12601 Phone 845.575.5050 Fax 845.575.5111 www.maristpoll.marist.edu New York State Campaign 2006 Final Primary Poll EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE: FRIDAY 6:00 P.M. SEPTEMBER 8, 2006 All references must be sourced WNBC/Marist Poll Contact: Dr. Lee M. Miringoff Dr. Barbara L. Carvalho Marist College 845.575.5050 This WNBC/Marist Poll of New York State reports: • Former HUD Secretary Andrew Cuomo leads his closest rival former NYC Public Advocate Mark Green by 22 percentage points: Andrew Cuomo is the frontrunner for the Democratic nomination for New York State’s attorney general with the support of 53% of Democrats likely to vote in Tuesday’s primary, including voters who are leaning toward a candidate. Former New York City Public Advocate Mark Green follows with 31%, and activist Sean Patrick Maloney trails with 6%. 9% of likely Democratic voters still remain undecided and another 17% say they may vote differently on primary day. Question Wording: If next Tuesday’s Democratic primary for attorney general of New York State were held today, whom would you support if the candidates are: Sean Andrew Mark Patrick Cuomo Green Maloney Other Undecided Likely Dems w/ Leaners September 2006 53% 31% 6% 1% 9% Likely Democrats September 2006 52% 30% 6% 1% 11% August 2006 46% 28% 10% 1% 15% Registered Democrats September 2006 49% 29% 6% 1% 15% August 2006 49% 24% 9% 3% 15% July 2006 40% 25% 7% 3% 25% Question Wording: Would you say that you strongly support (candidate’s name) somewhat support him, or do you think that you might vote differently on primary day? Strongly Somewhat Might Vote Likely Democrats Support Support Differently September 2006 49% 34% 17% Cuomo supporters 52% 33% 15% Green supporters 46% 37% 17% • Regardless of Tuesday’s primary outcome, both Cuomo and Green are early favorites against Republican Jeanine Pirro in the race for New York’s next attorney general this November: Both Andrew Cuomo and Mark Green lead Republican Jeanine Pirro by double- digits in early match-ups for the November contest for attorney general of New York. -

Congressional Delegation

NEW YORK STATE TH 115 Congressional Delegation U.S. SENATE CHARLES SCHUMER (D) KIRSTEN GILLIBRAND (D) New York State New York State 322 HSOB 478 RSOB Telephone: (202) 224-6542 Telephone: (202) 224-4451 Health Staff: Veronica Duron Health Staff: Alyson Northrup Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES YVETTE CLARKE (D) ELIOT ENGEL (D) District 9 District 16 Brooklyn Bronx 2058 RHOB 2462 RHOB Telephone: (202) 225-6231 Telephone: (202) 225-2464 Health Staff: Bridgette DeHart Health Staff: Catherine Barnao Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] CHRIS COLLINS (R) ADRIANO ESPAILLAT (D) District 27 District 13 Clarence Manhattan 1117 LHOB 1630 LHOB Telephone: (202) 225-5265 Telephone: (202) 225-4365 Health Staff: Ted Alexander Health Staff: Mark Howell Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] JOSEPH CROWLEY (D) JOHN FASO (R) District 14 District 19 Jackson Heights Kinderhook 1035 LHOB 1616 LHOB Telephone: (202) 225-3965 Telephone: (202) 225-5614 Health Staff: Nicole Cohen Health Staff: Patrick Rooney Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] DAN DONOVAN (R) BRIAN HIGGINS (D) District 11 District 26 Staten Island Buffalo 1541 LHOB 2459 RHOB Telephone: (202) 225-3371 Telephone: (202) 225-3306 Health Staff: Chris Del Beccaro Health Staff: Erin Meegan Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] JANUARY 2017 NEW YORK STATE 115TH CONGRESSIONAL -

Representational Style and Congressional Elections: New York's 19Th District in the 115Th Congress Margaret Mccormick Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2019 Representational Style and Congressional Elections: New York's 19th District in the 115th Congress Margaret McCormick Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation McCormick, Margaret, "Representational Style and Congressional Elections: New York's 19th District in the 115th Congress" (2019). Honors Theses. 2325. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/2325 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Representational Style and Congressional Elections: New York’s 19th District in the 115th Congress By Margaret McCormick * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Political Science UNION COLLEGE June, 2019 ABSTRACT MCCORMICK, MARGARET Representational Style and Congressional Elections: New York’s 19th District in the 115th Congress ADVISOR: Bradley Hays The disconnect between members of Congress and the American public is no secret. Of the three branches of government, the legislative branch is intended to be the most representative of the people. However, it consistently faces the lowest approval ratings among the American public. Although the public largely disapproves of Congress as a legislative body, most Americans support their own representative.1 This phenomenon is reflected in high reelection rates for congressional incumbents.