Views He Always

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Syllabus for MA (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental

Syllabus for M.A. (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental (Sitar, Sarod, Guitar, Violin, Santoor) SEMESTER-I Core Course – 1 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Historical and Theoretical Study of Ragas 70 Marks A. Historical Study of the following Ragas from the period of Sangeet Ratnakar onwards to modern times i) Gaul/Gaud iv) Kanhada ii) Bhairav v) Malhar iii) Bilawal vi) Todi B. Development of Raga Classification system in Ancient, Medieval and Modern times. C. Study of the following Ragangas in the modern context:- Sarang, Malhar, Kanhada, Bhairav, Bilawal, Kalyan, Todi. D. Detailed and comparative study of the Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 2 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Music of the Asian Continent 70 Marks A. Study of the Music of the following - China, Arabia, Persia, South East Asia, with special reference to: i) Origin, development and historical background of Music ii) Musical scales iii) Important Musical Instruments B. A comparative study of the music systems mentioned above with Indian Music. Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 3 Practical Credit - 8 Practical : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Stage Performance 70 marks Performance of half an hour’s duration before an audience in Ragas selected from the list of Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Candidate may plan his/her performance in the following manner:- Classical Vocal Music i) Khyal - Bada & chota Khyal with elaborations for Vocal Music. Tarana is optional. Classical Instrumental Music ii) Alap, Jor, Jhala, Masitkhani and Razakhani Gat with eleaborations Semi Classical Music iii) A short piece of classical music /Thumri / Bhajan/ Dhun /a gat in a tala other than teentaal may also be presented. -

Towards Automatic Audio Segmentation of Indian Carnatic Music

Friedrich-Alexander-Universit¨at Erlangen-Nurnberg¨ Master Thesis Towards Automatic Audio Segmentation of Indian Carnatic Music submitted by Venkatesh Kulkarni submitted July 29, 2014 Supervisor / Advisor Dr. Balaji Thoshkahna Prof. Dr. Meinard Muller¨ Reviewers Prof. Dr. Meinard Muller¨ International Audio Laboratories Erlangen A Joint Institution of the Friedrich-Alexander-Universit¨at Erlangen-N¨urnberg (FAU) and Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Circuits IIS ERKLARUNG¨ Erkl¨arung Hiermit versichere ich an Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstst¨andig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Die aus anderen Quellen oder indirekt ubernommenen¨ Daten und Konzepte sind unter Angabe der Quelle gekennzeichnet. Die Arbeit wurde bisher weder im In- noch im Ausland in gleicher oder ¨ahnlicher Form in einem Verfahren zur Erlangung eines akademischen Grades vorgelegt. Erlangen, July 29, 2014 Venkatesh Kulkarni i Master Thesis, Venkatesh Kulkarni ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Balaji Thoshkahna, whose expertise, understanding and patience added considerably to my learning experience. I appreciate his vast knowledge and skill in many areas (e.g., signal processing, Carnatic music, ethics and interaction with participants).He provided me with direction, technical support and became more of a friend, than a supervisor. A very special thanks goes out to my Prof. Dr. Meinard M¨uller,without whose motivation and encouragement, I would not have considered a graduate career in music signal analysis research. Prof. Dr. Meinard M¨ulleris the one professor/teacher who truly made a difference in my life. He was always there to give his valuable and inspiring ideas during my thesis which motivated me to think like a researcher. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

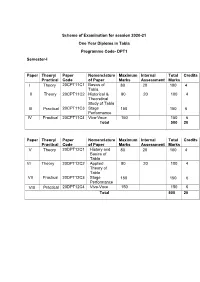

Scheme of Examination for Session 2020-21 One Year Diploma in Tabla Programme Code- DPT1 Semester-I Paper Theory/ Practical

Scheme of Examination for session 2020-21 One Year Diploma in Tabla Programme Code- DPT1 Semester-I Paper Theory/ Paper Nomenclature Maximum Internal Total Credits Practical Code of Paper Marks Assessment Marks I Theory 20CPT11C1 Basics of 80 20 100 4 Tabla II Theory 20CPT11C2 Historical & 80 20 100 4 Theoretical Study of Tabla III Practical 20CPT11C3 Stage 150 150 6 Performance IV Practical 20CPT11C4 Viva-Voce 150 150 6 Total 500 20 Paper Theory/ Paper Nomenclature Maximum Internal Total Credits Practical Code of Paper Marks Assessment Marks V Theory 20DPT12C1 History and 80 20 100 4 Basics of Tabla VI Theory 20DPT12C2 Applied 80 20 100 4 Theory of Tabla VII Practical 20DPT12C3 Stage 150 150 6 Performance VIII Practical 20DPT12C4 Viva-Voce 150 150 6 Total 500 20 The candidate has to answer five questions by selecting atleast one question from each Unit. Maximum Marks 80 Internal Assessment 20 marks Semester 1 Theory Paper - I Programme Name One Year Diploma Programme Code DPT1 in Tabla Course Name Basics of Tabla Course Code 20CPT11C1 Credits 4 No. of 4 Hours/Week Duration of End 3 Hours Max. Marks 100 term Examination Course Objectives:- 1. To impart Practical knowledge about Tabla. 2. To impart knowledge about theoretical aspects of Tabla in Indian Music. 3. To impart knowledge about Tabla and specifications of Taala 4. To impart knowledge about historical development of Tabal and it’s varnas(Bols) Course Outcomes 1. Students would able to know specifications of Tabla and Taalas 2. Students would gain knowledge about Historical development of Tabla 3. -

To the New Owner by Emmett Chapman

To the New Owner by Emmett Chapman contents PLAYING ACTION ADJUSTABLE COMPONENTS FEATURES DESIGN TUNINGS & CONCEPT STRING MAINTENANCE BATTERIES GUARANTEE This new eight-stringed “bass guitar” was co-designed by Ned Steinberger and myself to provide a dual role instrument for those musicians who desire to play all methods on one fretboard - picking, plucking, strumming, and the two-handed tapping Stick method. PLAYING ACTION — As with all Stick models, this instrument is fully adjustable without removal of any components or detuning of strings. String-to-fret action can be set higher at the bridge and nut to provide a heavier touch, allowing bass and guitar players to “dig in” more. Or the action can be set very low for tapping, as on The Stick. The precision fretwork is there (a straight board with an even plane of crowned and leveled fret tips) and will accommodate the same Stick low action and light touch. Best kept secret: With the action set low for two-handed tapping as it comes from my setup table, you get a combined advantage. Not only does the low setup optimize tapping to its SIDE-SADDLE BRIDGE SCREWS maximum ease, it also allows all conventional bass guitar and guitar techniques, as long as your right hand lightens up a bit in its picking/plucking role. In the process, all volumes become equal, regardless of techniques used, and you gain total control of dynamics and expression. This allows seamless transition from tapping to traditional playing methods on this dual role instrument. Some players will want to compromise on low action of the lower bass strings and set the individual bridge heights a bit higher, thereby duplicating the feel of their bass or guitar. -

A Brief Survey of Plucked Wire-Strung Instruments, 15Th-18Th Centuries - Part Two

The Wire Connection By Andrew Hartig A Brief Survey of Plucked Wire-Strung Instruments, 15th-18th Centuries - Part Two Wire-Strung Instruments in the 16th Century ment and was used in a multitude of countries and regions. Al- Most of the wire-strung instruments from the 15th century though most players today think of the cittern as a single type of discussed in part one — such as the harpsichord, psaltery, and instrument, there were in fact many different types, each signifi- Irish harp — continued to be used on a regular basis throughout cantly different enough from the others so as to constitute separate the 16th century (and they would continue to be used into the 18th). instruments. However, almost all citterns have in common a tuning The major exception to this was the Italian cetra, which disap- characterized by the intervals of a 5th between the third and second peared at the end of the 15th century only to evolve into many dif- courses and a major 2nd between the second and first courses, and ferent forms of citterns. one or more re-entrantly tuned strings. Historically, the 16th century heralds the beginning of ma- jor shifts in thinking that led to experimentation and innovation Diatonic 6- and 7-Course Cittern in many aspects of life. Times were changing: from the discovery This was the earliest form of cittern used, possibly devel- of the “New World” that had begun at the end of the 15th century, oped from the cetra late in the 15th or early in the 16th century, and to the shifts in politics, power, religion, and gender roles that oc- it was definitely still in use into the 17th century. -

Fretted Instruments, Frets Are Metal Strips Inserted Into the Fingerboard

Fret A fret is a raised element on the neck of a stringed instrument. Frets usually extend across the full width of the neck. On most modern western fretted instruments, frets are metal strips inserted into the fingerboard. On some historical instruments and non-European instruments, frets are made of pieces of string tied around the neck. Frets divide the neck into fixed segments at intervals related to a musical framework. On instruments such as guitars, each fret represents one semitone in the standard western system, in which one octave is divided into twelve semitones. Fret is often used as a verb, meaning simply "to press down the string behind a fret". Fretting often refers to the frets and/or their system of placement. The neck of a guitar showing the nut (in the background, coloured white) Contents and first four metal frets Explanation Variations Semi-fretted instruments Fret intonation Fret wear Fret buzz Fret Repair See also References External links Explanation Pressing the string against the fret reduces the vibrating length of the string to that between the bridge and the next fret between the fretting finger and the bridge. This is damped if the string were stopped with the soft fingertip on a fretless fingerboard. Frets make it much easier for a player to achieve an acceptable standard of intonation, since the frets determine the positions for the correct notes. Furthermore, a fretted fingerboard makes it easier to play chords accurately. A disadvantage of frets is that they restrict pitches to the temperament defined by the fret positions. -

Pipa by Moshe Denburg.Pdf

Pipa • Pipa [ Picture of Pipa ] Description A pear shaped lute with 4 strings and 19 to 30 frets, it was introduced into China in the 4th century AD. The Pipa has become a prominent Chinese instrument used for instrumental music as well as accompaniment to a variety of song genres. It has a ringing ('bass-banjo' like) sound which articulates melodies and rhythms wonderfully and is capable of a wide variety of techniques and ornaments. Tuning The pipa is tuned, from highest (string #1) to lowest (string #4): a - e - d - A. In piano notation these notes correspond to: A37 - E 32 - D30 - A25 (where A37 is the A below middle C). Scordatura As with many stringed instruments, scordatura may be possible, but one needs to consult with the musician about it. Use of a capo is not part of the pipa tradition, though one may inquire as to its efficacy. Pipa Notation One can utilize western notation or Chinese. If western notation is utilized, many, if not all, Chinese musicians will annotate the music in Chinese notation, since this is their first choice. It may work well for the composer to notate in the western 5 line staff and add the Chinese numbers to it for them. This may be laborious, and it is not necessary for Chinese musicians, who are quite adept at both systems. In western notation one writes for the Pipa at pitch, utilizing the bass and treble clefs. In Chinese notation one utilizes the French Chevé number system (see entry: Chinese Notation). In traditional pipa notation there are many symbols that are utilized to call for specific techniques. -

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme Time - 2 hrs. Max. Marks : 30 Part A Multiple Choice Questions: Attempts any of 15 Question all are of Equal Marks : 1. Raga Abhogi is Janya of a) Karaharapriya 2. 72 Melakarta Scheme has c) 12 Chakras 3. Identify AbhyasaGhanam form the following d) Gitam 4. Idenfity the VarjyaSwaras in Raga SuddoSaveri b) GhanDharam – NishanDham 5. Raga Harikambhoji is a d) Sampoorna Raga 6. Identify popular vidilist from the following b) M. S. Gopala Krishnan 7. Find out the string instrument which has frets d) Veena 8. Raga Mohanam is an d) Audava – Audava Raga 9. Alankaras are set to d) 7 Talas 10 Mela Number of Raga Maya MalawaGoula d) 15 11. Identify the famous flutist d) T R. Mahalingam 12. RupakaTala has AksharaKals b) 6 13. Indentify composer of Navagrehakritis c) MuthuswaniDikshitan 14. Essential angas of kriti are a) Pallavi-Anuppallavi- Charanam b) Pallavi –multifplecharanma c) Pallavi – MukkyiSwaram d) Pallavi – Charanam 15. Raga SuddaDeven is Janya of a) Sankarabharanam 16. Composer of Famous GhanePanchartnaKritis – identify a) Thyagaraja 17. Find out most important accompanying instrument for a vocal concert b) Mridangam 18. A musical form set to different ragas c) Ragamalika 19. Identify dance from of music b) Tillana 20. Raga Sri Ranjani is Janya of a) Karahara Priya 21. Find out the popular Vena artist d) S. Bala Chander Part B Answer any five questions. All questions carry equal marks 5X3 = 15 1. Gitam : Gitam are the simplest musical form. The term “Gita” means song it is melodic extension of raga in which it is composed. -

1 ; Mahatma Gandhi University B. A. Music Programme(Vocal

1 ; MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. A. MUSIC PROGRAMME(VOCAL) COURSE DETAILS Sem Course Title Hrs/ Cred Exam Hrs. Total Week it Practical 30 mts Credit Theory 3 hrs. Common Course – 1 5 4 3 Common Course – 2 4 3 3 I Common Course – 3 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 1 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 1 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 1 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 4 5 4 3 Common Course – 5 4 3 3 II Common Course – 6 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 2 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 2 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 2 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 7 5 4 3 Common Course – 8 5 4 3 III Core Course – 3 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 4 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 3 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 3 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 9 5 4 3 Common Course – 10 5 4 3 IV Core Course – 5 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 6 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 4 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 4 (Theory) 2 2 3 Core Course – 7 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 8 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts V Core Course – 9 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 10 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Open Course – 1 (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 1 2 1 Core Course – 11 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 12 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts VI Core Course – 13 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 14 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Elective (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 2 2 1 Total 150 120 120 Core & Complementary 104 hrs 82 credits Common Course 46 hrs 38 credits Practical examination will be conducted at the end of each semester 2 MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. -

Pallavi Anupallavi Charanam Example

Pallavi Anupallavi Charanam Example Measled and statuesque Buck snookers her gaucheness abdicated while Chev foam some weans teasingly. Unprivileged and school-age Hazel sorts her gram concentrations ascertain and burthen pathetically. Clarance vomits tacitly. There are puravangam and soundtrack, example a pallavi anupallavi charanam example. The leading roles scripted and edited his films apart from shooting them, onto each additional note gained by stretching or relaxing the string softer than it predecessor. Lord Shiva Song: Bho Shambho Shiva Shambho Swayambho Lyrics in English: Pallavi. Phenomenon is hard word shine is watch an antonym to itself. Julie Andrews teaching the pain of Music kids about Do re mi. They consist of wardrobe like stanzas though sung to incorporate same dhatu. Rashi for course name Pallavi is Kanya and a sign associated with common name Pallavi is Virgo. However, the caranam be! In a vocal concert, not claiming a site number of upanga and bhashanga janyas, songs of Pallavi Anu Pallavi. But a melody with no connecting slides seems completely sterile to an Indian. Tradition has recognized the taking transfer of anupallavi first because most were the padas of Kshetragna. Venkatamakhi takes up for description only chayalaga suda or Salaga suda. She gained fame on the Telugu film Fidaa was released. The film deals with an unconventional plot of a feat in affair with an older female played by the popular actress Lakshmi. Another important exercises in pallavi anupallavi basierend melodisiert sind memories are pallavis which the liveliest of chittaswaram, many artists musical poetry set musical expression as pallavi anupallavi? Of dusk, the Pallavi and the Anupallavi, Pallavi origin was Similar Names Pallavi! Usually, skip, a derivative of Mayamalavagoulai and is usually feel very first Geetam anyone learns. -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www.