Thesis-2002D-H498a.Pdf (2.669Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Certified School List MM-DD-YY.Xlsx

Updated SEVP Certified Schools January 26, 2017 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc. "I Am" School Inc. Y N Mount Shasta CA 41789 ‐ A ‐ A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe County Community College Y N Monroe MI 135501 A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe SH Y N North Hills CA 180718 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Lipscomb Academy Y N Nashville TN 434743 Aaron School Southeastern Baptist Theological Y N Wake Forest NC 5594 Aaron School Southeastern Bible College Y N Birmingham AL 1110 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. South University ‐ Savannah Y N Savannah GA 10841 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC Glynn County School Administrative Y N Brunswick GA 61664 Abcott Institute Ivy Tech Community College ‐ Y Y Terre Haute IN 6050 Aberdeen School District 6‐1 WATSON SCHOOL OF BIOLOGICAL Y N COLD SPRING NY 8094 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Milford High School Y N Highland MI 23075 Abilene Christian Schools German International School Y N Allston MA 99359 Abilene Christian University Gesu (Catholic School) Y N Detroit MI 146200 Abington Friends School St. Bernard's Academy Y N Eureka CA 25239 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Airlink LLC N Y Waterville ME 1721944 Abraham Joshua Heschel School South‐Doyle High School Y N Knoxville TN 184190 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School South Georgia State College Y N Douglas GA 4016 Abundant Life Christian School ELS Language Centers Dallas Y N Richardson TX 190950 ABX Air, Inc. Frederick KC Price III Christian Y N Los Angeles CA 389244 Acaciawood School Mid‐State Technical College ‐ MF Y Y Marshfield WI 31309 Academe of the Oaks Argosy University/Twin Cities Y N Eagan MN 7169 Academia Language School Kaplan University Y Y Lincoln NE 7068 Academic High School Ogden‐Hinckley Airport Y Y Ogden UT 553646 Academic High School Ogeechee Technical College Y Y Statesboro GA 3367 Academy at Charlemont, Inc. -

AMCSUS Issue 25

Association of Military Colleges and Schools of the United States Commandants Our AMCSUS Quarterly Newsletter Issue #25 Jul 2019 Commandants Gather Welcome 2019 SMC Conference New Leaders’ Workshop New AMCSUS Leaders Norwich will host the SMCs Massanutten will host the 2019 Commandants & spouses enjoyed 8-10 Sep. Registration New Leaders’ Workshop 15-17 beautiful Ogden, Utah for the Several member schools have package will be emailed out Sept. Expect email containing 2019 Commandants’ Workshop new leaders joining them in in late July registration package in late July 2019 Page 1/2 Pages 3 Pages 3 Page 3 2019 Commandant’s Workshop a Home Run! Participants engaged in a variety of timely and relevant topics: Military Charter overview; Utah Military Academy; flaws in American education; changes in educational environment, comparing forces of flight with success in life; addressing a America’s drug problem; Dean- Commandant relationship; and an open forum on collective action opportunities. AMCSUS Newsletter Jul 2019 ! Association of Military Colleges and Schools of the United States Commandants Workshop Blends Work with a Bit of Play! The 2019 Commandant’s Workshop was a home run! In addition to interesting/valuable presentations the group participated in a variety of cultural events: guided tour of historic Ogden’s colorful past; experienced two Grand Hotels; and enjoyed front-row seats to the 4th of July practice for the Tabernacle Choir at Temple. Spouses additionally visited Park City and learned to make candles! Hats off to Matt Throckmorton, -

SEVP Approved Schools As of Tuesday, June 08, 2010 Institution Name Campus Name City/State Date Approved - 1

SEVP Approved Schools As of Tuesday, June 08, 2010 Institution Name Campus Name City/State Date Approved - 1 - 1st Choice International, Inc. 1st Choice International, Inc. Glenview, IL 10/27/2009 1st International Cosmetology School 1st International Cosmetology School Lynnwood, WA 11/5/2004 - 4 - 424 Aviation Miami, FL 10/7/2009 - A - A F International School of Languages Inc. A F International School of Languages In Thousand Oaks, CA 6/3/2003 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Kirksville Coll of Osteopathic Medicine Kirksville, MO 3/10/2003 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. Flushing, NY 4/28/2009 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC ABC Beauty Academy Garland, TX 3/30/2006 Aberdeen Catholic School System Roncalli Aberdeen, SD 8/14/2003 Aberdeen College of English Los Angeles, CA 1/22/2010 Aberdeen School District 6-1 Aberdeen Central High School Aberdeen, SD 10/27/2004 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Abiding Savior Lutheran School Lake Forest, CA 4/16/2003 Abilene Christian Schools Abilene Christian Schools Abilene, TX 1/31/2003 Abilene Christian University Abilene Christian University Abilene, TX 2/5/2003 Abilene Independent School District Abilene Independent School District Abilene, TX 8/8/2004 Abington Friends School Abington Friends School Jenkintown, PA 7/15/2003 Above It All, Inc Benchmark Flight /Hawaii Flight Academy Kailua-Kona, HI 12/3/2003 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Tifton Campus Tifton, GA 1/10/2003 Abraham Joshua Heschel School New York, NY 1/22/2010 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School New York, NY 6/22/2006 Abundant Life Academy Kanab, UT 2/15/2008 Abundant Life Christian School Abundant Life Christian School Madison, WI 9/14/2004 Abundant Life School Sherwood, AR 10/25/2006 ABX Air, Inc. -

AMCSUS Newsletter Issue 201801

Association of Military Colleges and Schools of the United States AMCSUS Quarterly Newsletter Issue #19 Jan 2018 2018 New Member VMI Hosts VFMC Hosts Riverside Annual Conference Tarleton State University SMC Conference MJC Conference Raiders Amazing program awaits! Association unanimously Leaders & cadets gather Great discussion & Riverside Military Register now & submit your approved Tarleton as a full to share best practices engagement on multiple Academy wins 4th Best Practice by 1 Feb! member of AMCSUS. and build relationships! areas key to success consecutive Raider Challenge! Page 1 Page 2 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 2018 AMCSUS Annual Conference Theme: Wellness, Resilience & GRIT! 25-27 Feb 2018 Alexandria Westin, Alexandria VA Highlights: Sun Keynote Speaker: Col Art Athens, USMC (ret); Director Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership Welcome Reception: Hosted by AMCSUS’ generous sponsors Mon (0600 stretching/yoga for our Go-Getters!) Kick-off Speaker: Nancy Roy, Ed.D JED Resilience on Campus Wellness, Resilience & GRIT Workshop: DoD Updates: OSD - Cadet Command - USAF - USN/USMC - USCG Break-Out Sessions: SMCs, MJCs, Prep Schools “Unconferrence” Meeting Sleep & Nutrition Study: Andrew Herr Awards & Scholarship Banquet: Honored Speaker: LTG Ben Freakley Tue (0600 Zumba for our Go-Getters!) USA Resilience Program: COL Gregory Stokes Breakout Sessions: SMCs; MJCs; Prep Heads; Deans; Commandants Business Lunch: Treasurer’s Report, Outgoing President’s Comments, New Officers Contact Ray Rottman at 703-272-8406 or [email protected] for registration forms & information AMCSUS Newsletter Jan 2018 Association Association of Military of Military Colleges Colleges and and Schools Schools ofof the UnitedUnited States States AMCSUS Welcomes Tarleton State University! The Association’s membership unanimously approved Tarleton State University’s request for full membership in AMCSUS. -

Participating Educators and Exhibitors the ICEF North America Workshop

The ICEF North America Workshop - Miami Exclusively for educators from the US and Canada and international student recruitment agents focused on North America Loews Miami Beach Hotel • December 07 - 09, 2015 Participating educators and exhibitors Higher Education USA Canada • Alderson Broaddus University • Millikin University • Algonquin College • Alliant International University • North Central College • College of New Caledonia • American Public University System (APUS) • Northeastern University • Concordia University College of Alberta • Aquinas College • Northern Arizona University • Fairleigh Dickinson University - Vancouver • Arkansas State University • Norwich University • Lakehead University • ASA College • Plymouth State University • Royal Roads University • Atlantis University • Portland State University • Seneca College • California State University - Dominguez Hills • Presbyterian College • Thompson Rivers University (TRU) • California State University - San Jose State • Riverside City College • UBC Vantage College University • Saginaw Valley State University • UCW (University Canada West) • California State University, Fullerton • SAN IGNACIO COLLEGE • University of Victoria • Carroll University - Waukesha • San Mateo County Community College • Vancouver Island University • Cascadia College District • Chadron State College • Schiller International University - Florida • Chemeketa Community College • Seattle Central College • City University of New York - Brooklyn • Shorelight Education College • South Seattle College International -

Education Resources

EDUCATION RESOURCES Youth & Young Adult Options Scholarships for Military Children Program Over the past 15 years, commissaries have awarded more than $16 million in scholarships to more than 8,012 military children. The Scholarships for Military Children Program was created to recognize military families’ contributions to the readiness of the fighting force and to celebrate the commissary’s role in the military family community. At least one $2,000 scholarship is awarded at every commissary location that receives qualified applications. More than one scholarship per commissary may be available based on the response and funding. The scholarship provides for payment of tuition, books, lab fees and other college-related expenses. To be eligible, applicants must: Be under age 23 Be a dependent, unmarried child of active-duty personnel, Reserve Component members, National Guard and retired military members, survivors of service members who died while on active duty or survivors of individuals who died while receiving retired pay from the military Ensure that they and their sponsor are currently enrolled in the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS database) Have a current dependent military ID card Be enrolled or plan to enroll in a full-time undergraduate degree program at an accredited U.S. college or university in the fall term (Students attending a community or junior college must be enrolled in a program of studies that allows them to transfer directly into a four-year program.) Have a minimum, unweighted grade point average of 3.0 (on a 4.0 scale) Heroes' Legacy Scholarships The Heroes’ Legacy Scholarship honors those who fell in battle and all who died or became disabled through their active military service since Sept. -

AMCSUS Newsletter Issue 201807

Association of Military Colleges and Schools of the United States AMCSUS Quarterly Newsletter Issue #21 Jul 2018 Army & Navy Academy New Leader’s Workshop AMCSUS Competitions AMCSUS Financial Review Sets a New Standard! Fishburne Military School to host AMCSUS to host 3 competitions Member schools provided Commandant’s Workshop New Leaders Workshop in this Fall with award recognition financial expertise to review was on point! conjunction with the College Prep presented at the Feb 2019 Annual the Association’s financial Conference 23-25 Sep Conference processes Pages 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 4 AMCSUS Welcomes Utah Military Academy! With the Executive Committee’s unanimous support, AMCSUS members approved Utah Military Academy (UMA) as the Association’s newest member. UMA is a public charter school currently operating from two campuses not far from Salt Lake City. UMA’s Executive Director, Matt Throckmorton, expects total enrollment for the two schools to reach 950 this Fall. UMA’s mission is to prepare cadets as leaders to thrive in any competitive environment upon graduation with a focus on entrance into the military academies, ROTC scholarship programs in colleges and universities or other technically challenging opportunities related to the military culture. All of which result in maximizing their potential throughout life. Welcome Aboard! AMCSUS Newsletter Jul 2018 " Association of Military Colleges and Schools of the United States Army & Navy Academy Showcases Commandant’s Key Role in School Success The 2018 Commandant’s Conference agenda was packed with excellent topics. The dark side of social media (and more importantly how to keep your cadets informed and safe); counseling practices; iden- tifying and assisting cadets at risk; admissions protocols for US and international students; the critical relationship shared between the Head of School, the Dean and the Commandant; the how Army and Navy Academy employs the Durian Model to enhance its academics. -

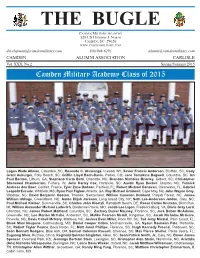

The Bugle: Spring/Summer 2015

THE BUGLE CAMDEN MILITARY ACADEMY 520 US HIGHWAY 1 NORTH CAMDEN, SC 29020 WWW.CAMDENMILITARY.COM [email protected] 800/948-6291 [email protected] CAMDEN ALUMNI ASSOCIATION CARLISLE Vol. XXX, No.2 Spring/Summer 2015 Camden Military Academy Class of 2015 Logan Wade Allman, Columbia, SC; Rosendo C. Alvarenga, Inwood, NY; Xavier Francis Anderson, Bluffton, SC; Cody Grant Auburger, Folly Beach, SC; Griffin Lloyd Bach-Davis, Parker, CO; Jace Tompkins Bagwell, Columbia, SC; Ian Paul Benton, Lilburn, GA; Stephano Carlo Betti, Charlotte, NC; Brandon Nicholas Brierley, Gilbert, SC; Christopher Sherwood Chamberlain, Fishers, IN; John Harley Cox, Hartsville, SC; Austin Ryan Decker, Clayton, NC; Yannick Andreas den Boer, Confort, France; Tyler Zane Dodson, Fairfield, FL; Robert Michael Donovan, Clearwater, FL; Gabriel Leopold Escude; Whitfield, MS;Ryan Paul Figlow, Atlanta, GA; Ray Michael Gradwell, Cape May, NJ; John Wayne Gray, Waxhaw, NC; David Benjamin Hooton, Thoniex, Switzerland; William Cameron Hubbard, Pisgah Forest, NC; James William Iddings, Greensboro, NC; Aaron Elijah Jackson, Long Island City, NY; Seth Lee-Anderson Jordan, Cary, NC; Paul Michael Kleiber, Summerville, SC; Charles John Kloetzli, Rehoboth Beach, DE; Reese Carlos Knutson, Birch Run, MI; William Alexander Michael Ladevich, Dardenne Prairie, MO; Jacob Lee Ligon, Fredericksburg, VA; Davis Gray Lord, Charlotte, NC; James Robert Maitland, Columbia, SC; Zachary Daniel Mauney, Florence, SC; Jack Dalton McAdams, Greenville, NC; Lee Marion McCabe, Anderson, SC; -

Camden Military Academy Camden, South Carolina

Camden Military Academy Camden, South Carolina Type: Boys’ boarding college-preparatory military school Grades: 7–12, PG Enrollment: School total: 300 Head of School: COL. Eric Boland, Headmaster mandatory teacher-supervised study period is Degree in Christian Counseling. Boland conducted four nights per week. All students completed The Executive Leadership and The School are monitored, and assignments are checked. Management Program from The Mendoza Students who maintain a B or better average Business College at The University of Notre While the Camden Military Academy tradition may elect to study in the Cline Library. The Dame in 2008. dates back to 1892, operations on the current library is available to other students during this time by faculty permission and is open campus began with the 1958–59 school year. Lt. Col. Pat Armstrong, a W est Point The Academy combines the traditions of daily to all students. The Academy encourages library use and has a full-time graduate, is the Commandant of Cadets. three institutions—Carlisle Military School, which operated in Bamberg, South Carolina, professional librarian available to assist in from 1892 to 1977; Camden Academy, which that usage. The faculty consists of 22 men and 4 women. was located on the current campus from 1949 Fifteen hold master’s degrees and 11 hold to 1957; and Camden Military Academy. Camden Military Academy high school bachelor’s degrees. Camden Military Academy, which was students have the opportunity to earn credit in founded by Col. James F. Risher and his son, both high school and college while taking College Placement Col. Lanning P. -

The Bugle: Spring 2017

JOIN US FOR HOMECOMING OCTOBER 28, 2017 THE BUGLE CAMDEN MILITARY ACADEMY 520 US HIGHWAY 1 NORTH CAMDEN, SC 29020 WWW.CAMDENMILITARY.COM [email protected] 800/948-6291 [email protected] CAMDEN ALUMNI ASSOCIATION CARLISLE Vol. XXXI, No.2 Spring 2017 Camden Military Academy Class of 2017 Vijay Victor Aysola, Jacksonville, FL; Chandler Lane Baker, Myrtle Beach, SC; Chance Traver Ball, Matthews, NC; John Alexander Beasley, Atlanta, GA; Edward Andre Benitez, Lake Forest, CA; Cole Martin Braasch, Simpsonville, SC; Aaron Matthew Cann, Hodges, SC; George Anthony Chestnut, Nashville, TN; James McMillan Covington, Jr., Mt. Pleasant, SC; Caleb Jude Crouch, Cecilia, LA; Jack Ryan Davern, Madison, CT; Christopher Jacob Dean, Waxhaw, NC; Joseph Braceland Degenhart, Columbia, SC; Miles Jacob Dudley, Gulfport, MS; Adam Joshua Dupzyk, Rocklin, CA; Lucas Ray Dyson, Summerville, SC; Logan Dax Edgecomb, Huntsville, AL; Brendan Allen Edwards, League City, TX; Jacob Baxter Edwards, Greenville, SC; Eric Fritzgerald Emery, Waterloo, SC; Jacob Thomas Epps, Lexington, SC; Bailey Harrison Ezell, Spartanburg, SC; John Matthew Ferguson, Jr., Houston, TX; Charles Nicholas Fields, Matthews, NC; Bryce Reid Fleming, Conyers, GA; Ned Eugene Gilleland, III, Hilton Head Island, SC; Barrett James Glasgow, Charleston, SC; Nathan Earl Grantham, Hartsville, SC; Zachary Michael Irtenkauf, Woodstock, GA; Mark Wesley Jackson, Matthews, NC; Colby Lynn Johnson, II, Newnan, GA; Connor Patrick Lentz, Mount Gilead, NC; Austin James Martin, Florence, SC; Ethan Grey -

Cma Info Sheet Intl 2019

Camden Military Academy Camden, South Carolina Type: Boys’ boarding college-preparatory military school Grades: 7–12, PG Enrollment: School total: 300 Head of School: COL. Eric Boland, Headmaster mandatory teacher-supervised study period is Degree in Christian Counseling. Boland conducted four nights per week. All students completed The Executive Leadership and The School are monitored, and assignments are checked. Management Program from The Mendoza Students who maintain a B or better average Business College at The University of Notre While the Camden Military Academy tradition may elect to study in the Cline Library. The Dame in 2008. dates back to 1892, operations on the current library is available to other students during this time by faculty permission and is open campus began with the 1958–59 school year. Lt. Col. Pat Armstrong, a W est Point The Academy combines the traditions of daily to all students. The Academy encourages library use and has a full-time graduate, is the Commandant of Cadets. three institutions—Carlisle Military School, which operated in Bamberg, South Carolina, professional librarian available to assist in from 1892 to 1977; Camden Academy, which that usage. The faculty consists of 22 men and 4 women. was located on the current campus from 1949 Fifteen hold master’s degrees and 11 hold to 1957; and Camden Military Academy. Camden Military Academy high school bachelor’s degrees. Camden Military Academy, which was students have the opportunity to earn credit in founded by Col. James F. Risher and his son, both high school and college while taking College Placement Col. Lanning P. -

AMCSUS Issue 2

Association of Military Colleges and Schools of the United States ASSOCIATION OF MILITARY COLLEGES AND SCHOOLS OF THE UNITED STATES Quarterly Newsletter AMCSUSIssue # 2 October 2013 Membership Marketing & Branding Military Band Festival Website Refresh Annual Conference The Executive The Marketing and To recognize next year’s Our “Refreshed” website Mark your calendars Committee agrees to Branding Committee has Centennial, our Annual is now operational, but now for the 2014 expand AMCSUS tapped “internal’ expertise Conference will kick off needs your updates to AMCSUS conference membership to Public to design questions for two with a military band optimize its effectiveness where we kick off our Military Academies surveys concert! Centennial Page 2!! Page 2!! Page 2 Page 3 Page 3 Military Education Story Goes Airborne! ! A fortuitous July lunch with Steve Mitchem (proud Fork Union Military Academy alumni) resulted in AMCSUS receiving an “offer we could not refuse”. During this meeting Steve, who is the Editor for U.S. Airways Magazine, candidly expressed his appreciation for the benefit his military education provided to his personal development and later successes. Having personally benefited from his emersion in the military education model, Steve recognized that the general public and more specifically his airline’s readership might be interested in learning about the “Military School Story”. !Fast forward two months and we are now putting the finishing touches on a 66-page editorial on military colleges and schools which will be seen by 6.5 million airline passengers in the November edition of the U.S. Airways Magazine. Despite obvious budgeting concerns, membership interest in the offer was very strong and eventually 28 schools committed to the U.S.