Biological Membranes a Molecular Perspective from Computation and Experiment Biological Membranes a Molecular Perspective from Computation and Experiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Massive Simulation Shows HIV Capsid Interacting with Its Environment 19 July 2017

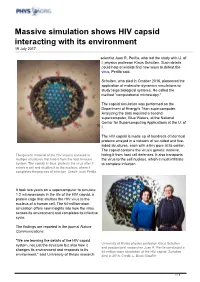

Massive simulation shows HIV capsid interacting with its environment 19 July 2017 scientist Juan R. Perilla, who led the study with U. of I. physics professor Klaus Schulten. Such details could help scientists find new ways to defeat the virus, Perilla said. Schulten, who died in October 2016, pioneered the application of molecular dynamics simulations to study large biological systems. He called the method "computational microscopy." The capsid simulation was performed on the Department of Energy's Titan supercomputer. Analyzing the data required a second supercomputer, Blue Waters, at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the U. of I. The HIV capsid is made up of hundreds of identical proteins arrayed in a network of six-sided and five- sided structures, each with a tiny pore at its center. The capsid contains the virus's genetic material, The genetic material of the HIV virus is encased in hiding it from host cell defenses. It also transports multiple structures that hide it from the host immune the virus to the cell nucleus, which it must infiltrate system. The capsid, in blue, protects the virus after it to complete infection. enters a cell and shuttles it to the nucleus, where it completes the process of infection. Credit: Juan Perilla It took two years on a supercomputer to simulate 1.2 microseconds in the life of the HIV capsid, a protein cage that shuttles the HIV virus to the nucleus of a human cell. The 64-million-atom simulation offers new insights into how the virus senses its environment and completes its infective cycle. -

HIV Structure by A&U

aumag.org http://aumag.org/wordpress/2013/07/29/hiv-structure/ HIV Structure by A&U Small Protein, Big Picture HIV capsid structure. Image by Klaus Schulten In order for HIV to replicate, the virus needs to carry its genetic material into new cells and then, once inside, to release it. This process is made possible in part by a protein shell: the HIV capsid, which functions to both protect the genetic material and then, at the right time, make it accessible. This makes the capsid an ideal antiviral target. One of the keys of disrupting this function is knowing the precise chemical structure of the HIV-1 capsid, and researchers, as reported in the journal Nature, have done just that. Up till now, scientists have been able to glimpse individual parts of the capsid but never a detailed molecular map of its whole, whose cone-shaped structure is formed by a polymorphic assemblage of more than 1,300 identical proteins. A dynamic view of the entire structure in atomic-level detail—namely, the interactions of 64 million atoms— was made possible with the use of the supercomputer Blue Waters at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois. Thanks to the largest computer simulation ever run, the digital model was created by researchers Klaus Schulten and Juan Perilla at the University of Illinois, who built on previous research and their own simulations of how the building blocks of the proteins—hexagons and pentagons, arranged in ever-changing patterns—interacted and fit together, and in what numbers. -

Blue Waters Computing System

GPU Clusters for HPC Bill Kramer Director of Blue Waters National Center for Supercomputing Applications University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign National Center for Supercomputing Applications University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign National Center for Supercomputing Applications: 30 years of leadership • NCSA • R&D unit of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign • One of original five NSF-funded supercomputing centers • Mission: Provide state-of-the-art computing capabilities (hardware, software, hpc expertise) to nation’s scientists and engineers • The Numbers • Approximately 200 staff (160+ technical/professional staff) • Approximately 15 graduate students (+ new SPIN program), 15 undergrad students • Two major facilities (NCSA Building, NPCF) • Operating NSF’s most powerful computing system: Blue Waters • Managing NSF’s national cyberinfrastructure: XSEDE Source: Thom Dunning Petascale Computing Facility: Home to Blue Waters • Blue Waters • 13PF, 1500TB, 300PB • >1PF On real apps • NAMD, MILC, WRF, PPM, NWChem, etc • Modern Data Center • Energy Efficiency • 90,000+ ft2 total • LEED certified Gold • 30,000 ft2 raised floor • Power Utilization Efficiency 2 = 1.1–1.2 20,000 ft machine room gallery Source: Thom Dunning Data Intensive Computing Personalized Medicine w/ Mayo LSST, DES Source: Thom Dunning NCSA’s Industrial Partners Source: Thom Dunning NCSA, NVIDIA and GPUs • NCSA and NVIDIA have been partners for over a decade, building the expertise, experience and technology. • The efforts were at first exploratory and small -

List of Publications Professor Klaus Schulten Departments of Physics, Chemistry, and Biophysics University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Printed November 1, 2002

List of Publications Professor Klaus Schulten Departments of Physics, Chemistry, and Biophysics University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Printed November 1, 2002 [1] Klaus Schulten and Martin Karplus. On the origin of a low-lying forbidden transition in polyenes and related molecules. Chem. Phys. Lett., 14:305–309, 1972. [2] Robert R. Birge, Klaus Schulten, and Martin Karplus. Possible influence of a low-lying “covalent” excited state on the absorption spectrum and photoisomerization of 11-cis retinal. Chem. Phys. Lett., 31:451–454, 1975. [3] Klaus Schulten and Roy G. Gordon. Exact recursive evaluation of 3j- and 6j-coefficients for quantum- mechanical coupling of angular momenta. J. Math. Phys., 16:1961–1970, 1975. [4] Klaus Schulten and Roy G. Gordon. Semiclassical approximation to 3j- and 6j-coefficients for quantum- mechanical coupling of angular momenta. J. Math. Phys., 16:1971–1988, 1975. [5] Klaus Schulten, I. Ohmine, and Martin Karplus. Correlation effects in the spectra of polyenes. J. Chem. Phys., 64:4422–4441, 1976. [6] Klaus Schulten and Roy G. Gordon. Quantum theory of angular momentum coupling in reactive collisions. J. Chem. Phys., 64:2918–2938, 1976. [7] Klaus Schulten and Roy G. Gordon. Recursive evaluation of 3j- and 6j-coefficients. Comput. Phys. Commun., 11:269–278, 1976. [8] Klaus Schulten, H. Staerk, Albert Weller, Hans-Joachim Werner, and B. Nickel. Magnetic field depen- dence of the geminate recombination of radical ion pairs in polar solvents. Z. Phys. Chem., NF101:371– 390, 1976. [9] Klaus Schulten. Quantum mechanical propensity rules for the transfer of angular momentum in three- atom reactions. Ber. -

Understanding How Birds Navigate

10.1117/2.1200909.1804 Understanding how birds navigate Ilia A. Solov’yov and Klaus Schulten A proposed model for migrating birds’ magnetic sense can withstand moderate orientational disorder of a key protein in the eye. Creatures as varied as salmon, honeybees, and migratory birds such as European robins have an intriguing ‘sixth’ sense that allows them to distinguish north from south.1–4 Yet despite decades of study, the physical basis of this magnetic sense re- mains elusive. Detailed understanding of magnetoreception in animals has tremendous applications. For example, it is well known that windmills constructed in the wrong places, espe- cially older ones, cause many bird deaths. Shielding these struc- tures with magnetic fields may reduce the death toll by keeping the animals away from the dangerous area. Similar shields could be used to protect airports from birds, as they regularly collide with airborne airplanes, causing severe problems. Damage by birds and other wildlife striking aircraft annually amounts to well over $600 million for US civil and military aviation and over 219 people have been killed worldwide as a result of wildlife Figure 1. Structure of cryptochrome, likely involved in avian mag- strikes since 1988.5 netoreception. The protein internally binds the FADH (the semi- Migratory birds’ magnetic sense may be based on the pro- reduced form of flavin adenine dinucleotide) cofactor, which governs its tein cryptochrome, found in the retina, the light-sensitive part of functioning capabilities. The signaling state is achieved through a the eyes. Cryptochrome’s functional capabilities depend on its light-induced electron-transfer reaction involving a chain of three orientation in an external magnetic field.6, 7 But it is present in tryptophan amino acids, Trp400, Trp377, and Trp324. -

CV (December 21, 2020) 1 Braun, Rosemary I

Rosemary Braun Curriculum Vitae Education Ph.D. (Physics) University of Illinois, Urbana–Champaign 2004 Dissertation: Molecular Dynamics Studies of Interfacial Effects on Protein Conformation Advisor: Prof. K. Schulten, Physics (Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group) M.P.H. (Biostatistics) Johns Hopkins–Bloomberg School of Public Health 2006 Thesis: Identifying Differentially Expressed Gene–Pathway Combinations Advisor: Prof. G. Parmigiani, Biostatistics B.Sc. (Physics) Stony Brook University (SUNY Stony Brook) 1996 Honors College Thesis: Binary Pulsar Evolution Advisor: Prof G. E. Brown, Physics (Nuclear Theory Group) Academic Appointments Northwestern University Associate Professor 01/2021—present Molecular BioSciences [primary] Physics & Astronomy [courtesy] Assistant Professor 10/2011—12/2020 Biostatistics, Preventive Medicine [primary] Physics & Astronomy [courtesy] Engineering Sciences & Applied Mathematics [courtesy] Institute and center affiliations: Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems (NICO) R.H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center NSF-Simons Center for Quantitative Biology National Institutes of Health Postdoctoral Fellow, National Cancer Institute 2005–2011 Laboratory of Population Genetics (PI: Ken Buetow) University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Postdoctoral Research Associate, Department of Physics 2004–2005 Graduate Research Assistant, Department of Physics 1997–2004 Stony Brook University (SUNY Stony Brook) Undergraduate Research Assistant, Department of Physics 1994–1995 Undergraduate Teaching Assistant, Department of Mathematics 1994–1995 Publications (Chronological) * corresponding author; y Braun lab student/postdoc [1] Justin Gullingsrud, Rosemary Braun, and Klaus Schulten. Reconstructing potentials of mean force through time series analysis of steered molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of Computational Physics, 151:190–211, 1999. CV (December 21, 2020) 1 Braun, Rosemary I. [2] Rosemary Braun, Mehmet Sarikaya, and Klaus Schulten. Genetically engineered gold-binding polypeptides: Structure prediction and molecular dynamics. -

Klaus Schulten Department of Physics and Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Klaus Schulten Department of Physics and Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign GTC, San Jose Convention Center, CA | Sept. 20–23, 2010 GPU and the Computational Microscope Accuracy • Speed-up • Unprecedented Scale Investigation of drug (Tamiflu) resistance of the “swine” flu virus demanded fast response! Computational Microscope Views at Atomic Resolution... RER Rs SER The Computational C GA Microscope E N M RER L ...how living cells maintain health and battle disease Our Microscope is Made of... Chemistry NAMD Software 100 10 ns/day Virus 1 128 256 512 1024 2048 4096 8192 16384 32768 40,000 registered users cores Physics Math (repeat one billion times = microsecond) ..and Supercomputers Our Microscope is a “Tool to Think” Graphics, Geometry Carl Woese Genetics Physics Lipoprotein particle HDL Ribosomes in whole cell T. Martinez, Stanford U. VMD Analysis Engine Atomic coordinates 140,000 Registered Users Volumetric data, electronsa Science 1: Poliovirus Infection Virus Rigid Capsid Virus Genome Inside Capsid membrane attachment indentation to cell Cell Membrane Surface Receptor How does this work? Answer requires 100 million atom long-time simulation TT Virus Genome Inside Cell Loose Capsid Science 1: Virus Capsid Mechanics Atomic Force Microscope — Hepatitis B Virus — 500 Experiment Simulation 400 300 200 Force (pN) 100 0 -20-40 -2080 0 180 20 280 40 380 60 480 Indentation (Å) GPU Solution 1: Time-Averaged Electrostatics • Thousands of trajectory frames • 1.5 hour job reduced to 3 min -

Physics of Living Systems

Physics of Living Systems International Meeting of the Physics of Living Systems Student Research Network 21–24 July 2014 — Munich Contents Organizers Program - 1 Prof. Don Lamb Prof. Dieter Braun Abstracts Talks - 5 (LMU Munich) & Poster Abstracts - 34 Prof. Zan Luthey-Schulten (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) List of Participants - 59 Management Team: Lunch Spots - 63 Marilena Pinto, Gabriela Milia (SFB 1032 “Nanoagents”) Dr. Susanne Hennig, Anna Kager (Center for NanoScience) Locations 64 Ludwig-Maximilians Universität (LMU) Munich Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1 Public Transport - 65 D-807539 Munich, Germany Internet Access - 65 www.sfb1032.physik.uni-muenchen.de www.cens.de Partner: Venue Financial Support: Deutsches Museum (July 21) Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Ehrensaal Museumsinsel 1 80538 Munich & National Science Foundation LMU Munich (July 22-24) Physics Department Lecture Hall H030 Schellingstr. 4 80799 Munich PROGRAM Monday, July 21 Deutsches Museum, Ehrensaal 9:15 am - Welcome 10:55 am Bernd Huber, President Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU) Munich Don Lamb, LMU Munich LMU Munich Erwin Frey: Pattern Formation and Collective Phenomena in Biological Systems Dieter Braun: Probing Molecular Evolution, Cellular Kinetics and Biomolecule Binding with Microthermal Gradients Ulrike Gaul: Systems Biology of Gene Regulation: Dissecting the Core Promoter Coffee break 11:20 am- Technische Universität Munich 12:35 pm Matthias Rief: Mechanics of Single Protein Molecules Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry Elena Conti: Visualizing -

Jin Yu 喻进 University of California, Irvine Email: [email protected]

Curriculum Vitae Jin Yu 喻进 University of California, Irvine https://www.physics.uci.edu/jin-yu Email: [email protected] EDUCATION ➢ PhD: Department of Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) Aug, 2007 Advisor: Professor Klaus Schulten ➢ MS: Department of Finance, UIUC May, 2007 ➢ MS: Department of Physics, Tsinghua University (Beijing, China) Jan, 2001 Advisor: Professor Guozhen Wu 吴国祯 ➢ BS: Department of Physics, Tsinghua University 清华大学物理系 June, 1998 EMPLOYMENT HISTORY ➢ Assistant Professor, Department of Physics and Astronomy (from July 2019), the NSF-Simons Center of Multiscale Cell Fate (CMCF) Research, and the Department of Chemistry (from March 2020), University of California, Irvine ➢ Principal Investigator, Complex System Research Division, Beijing Computational Science Research Center (CSRC) 2012 – June 2019 ➢ Postdoc with George Oster in Molecular & Cellular Biology and Bustamante Lab in the Physics Department, University of California, Berkeley 2007 – 2011 ➢ Research assistant in Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group, Beckman Institute, UIUC 2003 – 2007 ➢ Teaching assistant in undergraduate Quantum Physics and graduate Quantum Mechanics, Department of Physics, UIUC 2001- 2002 ➢ Research assistant in Molecular and Nano Sciences Laboratory, Department of Physics, Tsinghua University 1998- 2001 FUNDING AWARDS ➢ National Science Foundation (NSF) (PI) RAPID: Dissecting inhibitor impacts on viral polymerase and fidelity control of RNA-synthesis in SARS-CoV-2, Award # MCB-2028935 2020-2021 ➢ National Natural -

Why Steered Molecular Dynamics?

Klaus Steered Molecular Dynamics Schulten Introduction and Examples Justin avidin Gullingsrud Hui Lu Sergei Izrailev biotin Rosemary Braun Barry Isralewitz Why Steered Molecular Dynamics? Dorina Kosztin - Accelerates processes to simulation time scales (ns) Ferenc -Yields explanations of biopolymer mechanics Molnar - Complements Atomic Force Microscopy Acknowledgements: - Finds underlying unbinding potentials Fernandez group, Mayo C.; Vogel group, U. Washington NIH, NSF, Carver Trust - Generates and tests Hypotheses Mechanical Functions of Proteins Forces naturally arise in cells and can also be substrates (ATPase) products (myosin) signals (integrin) of cellular processes Atomic Force Microscopy Experiments of Ligand Unbinding Florin et al., Science 264:415 (1994) avidin biotin AFM Force Displacement of AFM tip Biotin Chemical structure of biotin Atomic Force Microscopy Experiments of Ligand Unbinding Florin et al., Science 264:415 (1994) avidin biotin Force Displacement of AFM tip Biotin AFM NIH Resource for Macromolecular Modeling and Bioinformatics Theoretical Biophysics Group, Beckman Institute, UIUC Pulling Biotin out of Avidin Molecular dynamics study of unbinding of the avidin-biotin complex. Sergei Izrailev, Sergey Stepaniants, Manel Balsera, Yoshi Oono, and Klaus Schulten. Biophysical Journal, 72:1568-1581, 1997. SMD of Biotin Unbinding: What We Learned biotin slips out in steps, guided by amino acid side groups, water molecules act as lubricant, MD overestimates extrusion force http://www.ks.uiuc.edu Israilev et al., Biophys. -

Architecture and Mechanism of the Light-Harvesting Apparatus of Purple Bacteria

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 95, pp. 5935–5941, May 1998 Colloquium Paper This paper was presented at the colloquium ‘‘Computational Biomolecular Science,’’ organized by Russell Doolittle, J. Andrew McCammon, and Peter G. Wolynes, held September 11–13, 1997, sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences at the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center in Irvine, CA. Architecture and mechanism of the light-harvesting apparatus of purple bacteria XICHE HU,ANA DAMJANOVIC´,THORSTEN RITZ, AND KLAUS SCHULTEN Beckman Institute and Department of Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801 ABSTRACT Photosynthetic organisms fuel their metab- PSU, an array of light-harvesting complexes captures light and olism with light energy and have developed for this purpose an transfers the excitation energy to the photosynthetic RC. This efficient apparatus for harvesting sunlight. The atomic struc- article focuses on the primary processes of light harvesting and ture of the apparatus, as it evolved in purple bacteria, has been electronic excitation transfer that occur in the PSU, and constructed through a combination of x-ray crystallography, describes the role of molecular modeling in elucidating the electron microscopy, and modeling. The detailed structure underlying mechanisms. and overall architecture reveals a hierarchical aggregate of In most purple bacteria, the photosynthetic membranes pigments that utilizes, as shown through femtosecond spec- contain two types of light-harvesting complexes, light- troscopy and quantum physics, elegant and efficient mecha- harvesting complex I (LH-I) and light-harvesting complex II nisms for primary light absorption and transfer of electronic (LH-II) (7). LH-I is found surrounding directly the RCs (8, 9), excitation toward the photosynthetic reaction center. -

Klaus Schulten on How Birds Navigate

earthsky.org http://earthsky.org/earth/klaus-schulten-on-how-birds-navigate Klaus Schulten on how birds navigate Lindsay Patterson Today, Adam Bergner, of Linkoping, Sweden, asks “how are birds able to navigate?” There are many theories, and a recent one came from Klaus Schulten, a biophysicist at the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign. He said birds usually navigate by physical landmarks, like highways or coastlines. But, in extreme weather or as they fly over oceans, they use a sort of internal compass. Klaus Schulten: Many of us think that there are two compass senses in birds and other animals: one, that likely relies on magnetite. The other one is a biochemical reaction that is connected with visual system. Magnetite – a mineral with magnetic properties – is found in some birds’ beaks. Schulten believes it helps birds identify strong or weak magnetic fields on Earth’s surface. He thinks birds also utilize Earth’s pervasive, global magnetic field – the one that guides our compasses. Klaus Schulten: And that is more the general map that they need to use when they are in completely unknown territory. Schulten believes that ability comes from a light-sensing protein, located in only one eye of the bird. The protein picks up signals, based on light, to send messages to the brain about the direction of the magnetic field. Klaus Schulten: The problem – but also partially the answer – of how birds navigate is that one cannot see an obvious compass. But rather, one has to get cues from the behavior responses of the bird. One important clue is that apparently light influences how birds navigate.