Recent Cases: the Right to Vote in Southern Primaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

“The Negroes’ Temporary Farewell” JIM CROW AND THE EXCLUSION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS FROM CONGRESS, 1887–1929 On December 5, 1887, for the first time in almost two decades, Congress convened without an African-American Member. “All the men who stood up in awkward squads to be sworn in on Monday had white faces,” noted a correspondent for the Philadelphia Record of the Members who took the oath of office on the House Floor. “The negro is not only out of Congress, he is practically out of politics.”1 Though three black men served in the next Congress (51st, 1889–1891), the number of African Americans serving on Capitol Hill diminished significantly as the congressional focus on racial equality faded. Only five African Americans were elected to the House in the next decade: Henry Cheatham and George White of North Carolina, Thomas Miller and George Murray of South Carolina, and John M. Langston of Virginia. But despite their isolation, these men sought to represent the interests of all African Americans. Like their predecessors, they confronted violent and contested elections, difficulty procuring desirable committee assignments, and an inability to pass their legislative initiatives. Moreover, these black Members faced further impediments in the form of legalized segregation and disfranchisement, general disinterest in progressive racial legislation, and the increasing power of southern conservatives in Congress. John M. Langston took his seat in Congress after contesting the election results in his district. One of the first African Americans in the nation elected to public office, he was clerk of the Brownhelm (Ohio) Townshipn i 1855. -

SS8H11 Standards SS8H11 the Student Will Evaluate the Role of Georgia in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

© 2015 Brain Wrinkles SS8H11 Standards SS8H11 The student will evaluate the role of Georgia in the modern civil rights movement. a. Describe major developments in civil rights and Georgia’s role during the 1940s and 1950s; include the roles of Herman Talmadge, Benjamin Mays, the 1946 governor’s race and the end of the white primary, Brown v. Board of Education, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the 1956 state flag. b. Analyze the role Georgia and prominent Georgians played in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s; include such events as the founding of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Sibley Commission, admission of Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter to the University of Georgia, Albany Movement, March on Washington, Civil Rights Act, the election of Maynard Jackson as mayor of Atlanta, and the role of Lester Maddox. c. Discuss the impact of Andrew Young on Georgia. © 2015 Brain Wrinkles © 2015 Brain Wrinkles SS8H11a • The white primary system helped white supremacists control Georgia’s politics because it only allowed whites to vote in statewide primary elections. • The white primary system completely cut African Americans out of the political process. • In 1944, the Supreme Court struck down a similar white primary system in Texas, ultimately leading to the end of Georgia’s white primary in 1946. © 2015 Brain Wrinkles • 1946 also saw one of the most controversial episodes in Georgia politics. • Eugene Talmadge was elected governor for the fourth time, but he died before he could take office. • Many of his supporters knew that he was ill, so they scratched his name off the ballot and wrote in his son’s name, Herman Talmadge. -

Elmore V. Rice Et Al.: the Court Case That Defies a Narrative”

Phi Alpha Theta Pacific Northwest Conference, 8–10 April 2021 Gerrit Sterk, Western Washington University, undergraduate student, “Elmore v. Rice et al.: The Court Case that Defies a Narrative” Abstract: Studying and explaining Elmore v. Rice et al., a voting rights case that took place in 1947 in Columbia, South Carolina, provides an opportunity to enrich a new development in the historiography of the Civil Rights Movement. How this case was supported by Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP has been studied, but how it and similar early grassroots actions contributed to what some historians are now calling “the long civil rights movement” has not, one that began long before the Brown decision of 1954. Additionally, how this case emerged out of the grassroots political culture of Waverly, a middle-class Black community in Columbia, adds to what scholars are beginning to understand about the “long grassroots civil rights movement,” one that had its roots in the daily negotiations of African Americans with the condition of enslavement, as explained by Steven Hahn in his work, A Nation Under Our Feet. Utilizing the original court case records, in combination with documents on the Waverly community and the plaintiff in the case, George Elmore, this paper will explain how this grassroots community initiative emerged—and then combined with an ongoing NAACP initiative to chip away at Jim Crow restrictions against Black political empowerment. 1 Elmore v. Rice et al.: The Court Case That Defies a Narrative. Its Historical and Historiographical Meaning Gerrit Sterk Undergraduate Western Washington University 2 George Elmore poses outside the Waverly 5¢ and 10¢ Store, circa 1945. -

Deconstructing Democracy: How Congressional Elections Collapsed in the South After Reconstruction

Deconstructing Democracy: How Congressional Elections Collapsed in the South After Reconstruction M.P. Greenberger A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Political Science. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Christopher J. Clark Marc Hetherington Jason Roberts c 2020 M.P. Greenberger ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT M.P. Greenberger: Deconstructing Democracy: How Congressional Elections Collapsed in the South After Reconstruction (Under the direction of Jason Roberts) As Federal Troops began pulling out of the South in 1877, steps made towards full enfranchisement of black southerners, competitive elections, and representative democracy collapsed. Over the course of the next fifty years, white \Redeemers" established a sub-national authoritarian regime that encompassed nearly the entire formerly Confederate South { reasserting the rule of political and economic white supremacy. Although Redeemers ultimately succeeded in their attempts to establish an authoritarian system of government under the Democratic party label, the effectiveness of their tactics varied throughout the region. Analyzing an original dataset of congressional elections returns from 1870 to 1920, I uncover significant variation in the rate and extent of democratic backsliding throughout the South. I use historical census data to measure the effect of education, racial composition, legacy of slavery, institutional reforms, and economic systems on the rate of democratic collapse. My findings suggest that racial and partisan factors motivated democratic collapse, and that institutional reforms such as the poll tax and white primary elections merely formalized and further entrenched an already ongoing process of authoritarian encroachment. -

The Reconstruction Trope: Politics, Literature, and History in the South, 1890-1941 Travis Patterson Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2018 The Reconstruction Trope: Politics, Literature, and History in the South, 1890-1941 Travis Patterson Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Patterson, Travis, "The Reconstruction Trope: Politics, Literature, and History in the South, 1890-1941" (2018). All Theses. 2917. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2917 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RECONSTRUCTION TROPE: POLITICS, LITERATURE, AND HISTORY IN THE SOUTH, 1890-1941 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History by Travis Patterson August 2018 Accepted by: Dr. Paul Anderson, Committee Chair Dr. Rod Andrew Jr. Dr. Vernon Burton ABSTRACT This thesis examines how white southerners conceptualized Reconstruction from 1890 to 1941, with an emphasis on the era between the First and Second World Wars. By analyzing Reconstruction as it appears in political rhetoric, professional and amateur history, and southern literature, the thesis demonstrates how white southerners used the ‘tragic’ story of Reconstruction to respond to developments in their own time. Additionally, this thesis aims to illuminate the broader cultural struggle over Reconstruction between the First and Second World Wars. This thesis ultimately argues that the early revisionism in Reconstruction historiography was part of a broader reassessment of Reconstruction that took place in southern culture after the First World War. -

Jim Crow Laws. in the Streets, Resistance Turned Violent

TEACHING TEACHING The New Jim Crow TOLERANCE LESSON 4 A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER TOLERANCE.ORG Jim Crow as a Form of Racialized Social Control THE NEW JIM CROW by Michelle Alexander CHAPTER 1 The Rebirth of Caste The Birth of Jim Crow The backlash against the gains of African Americans in the Reconstruction Era was swift and severe. As African Americans obtained political power and began the long march to- ward greater social and economic equality, whites reacted with panic and outrage. South- ern conservatives vowed to reverse Reconstruction …. Their campaign to “re- deem” the South was reinforced by a resurgent Ku Klux Klan, which fought a BOOK terrorist campaign against Reconstruction governments and local leaders, EXCERPT complete with bombings, lynchings, and mob violence. The terrorist campaign proved highly successful. “Redemption” resulted in the withdrawal of federal troops from the South and the effective aban- donment of African Americans and all those who had fought for or supported an egalitarian racial order. The federal government no longer made any effort to enforce federal civil rights legislation … . Once again, vagrancy laws and other laws defining activities such as “mischief ” and “insult- ing gestures” as crimes were enforced vigorously against blacks. The aggressive enforce- ment of these criminal offenses opened up an enormous market for convict leasing, in Abridged excerpt which prisoners were contracted out as laborers to the highest private bidder. from The New Jim Crow: Mass Incar- Convicts had no meaningful legal rights at this time and no effective redress. They were ceration in the Age understood, quite literally, to be slaves of the state. -

The Mississippi Democratic Primary of July, 1946 : a Case Study

The Woman's College of The University of North Carolina LIBRARY C<3 COLLEGE COLLECTION Gift of Thomas Lane Moore, III MOORE-THOMAS LANE, III: The Mississippi Democratic Primary of July, 1946: A Case Study. (1967) Directed by: Dr. Hichard Bardolph. pp. 99. The thesis illustrates the extreme hostility to the possibility of any change in the status quo of race relations that manifested itself in the Mississippi Democratic primary of 19^6. It focuses primarily on the Senatorial campaign of that contest in which Theodore G. Bilbo successfully used the race issue (in spite of the attempt of each of his opponents to assure the electorate that he could best defend "white supremacy") to obtain his reelection. It points out that editorial comments from all sections of the state, while often hostile to Bilbo, were in favor of the preservation of the existing racial conditions in Mississippi. It shows that Negroes who attempted to register and vote in Mississippi often had to run a gauntlet of extra-legal intimidation if they stood fast to their purpose. The last section of the thesis points out that the senatorial campaign and the subsequent Senate investigation of the methods used by Bilbo to win the election convinced some Northerners that much would have to be done In Mississippi if Negro citizens of that state were going to be able to enjoy the rights that the federal courts said they were entitled to. THE MISSISSIPPI DEMOCRATIC PRIMARY OF JULY, 194.6: A CASE STUDY by Thomas Lane Moore, III A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Sohool at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History Greensboro January, 1966 Approved by Director APPROVAL SHEET This thesis has been approved by the following committee of the Faoulty of the Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

James U. Blacksher Attorney at Law Phone: 205-591-7238 P.O. Box 636 Birmingham, AL 35201 Fax: 866-845-4395 E-Mail: Jblacksher@Ns

James U. Blacksher P.O. Box 636 Attorney at Law Birmingham, AL 35201 Phone: 205-591-7238 Fax: 866-845-4395 E-mail: [email protected] Statement of James U. Blacksher The Subcommittee on Elections of the Committee on House Administration Field Hearing, Birmingham, AL, May 13, 2019 Voting Rights and Election Administration in Alabama My name is James Blacksher. Thank you for inviting me to testify. I am a white native of Alabama and have been practicing law in Alabama since 1971, engaged primarily in representing African Americans in civil rights and voting rights litigation. I argued – and lost – City of Mobile v. Bolden (1980) in the Supreme Court, but with the help of co-counsel we won on remand to the district court. I testified in Congressional hearings leading to enactment of the 1982 Voting Rights Amendments. Four years later the Supreme Court in Thornburg v. Gingles (1986) cited and adopted the three-prong test proposed in my Hastings Law Review article for purposes of establishing a violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. With Edward Still and Larry Menefee, I represented plaintiffs in the Dillard v. Crenshaw County class action, which changed the method of electing members of over 180 local governments in Alabama. I have represented African Americans in litigation following redistricting of the Alabama House and Senate districts and Congressional districts in every decade since the 1980 census. Most recently, I represented the plaintiffs before the Supreme Court in Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama (2015), which held that many of the Alabama House and Senate districts were racially gerrymandered. -

Mississippi Freedom Summer, 1964

Mississippi Freedom Summer, 1964 By Bruce Hartford Copyright © 2014. All rights reserved. For the winter soldiers of the Freedom Movement Contents Origins The Struggle for Voting Rights in McComb Mississippi Greenwood & the Mississippi Delta The Freedom Ballot of 1963 Freedom Day in Hattiesburg Mississippi Summer Project The Situation The Dilemma Pulling it Together Mississippi Girds for Armageddon Washington Does Nothing Recruitment & Training 10 Weeks That Shake Mississippi Direct Action and the Civil Rights Act Internal Tensions Lynching of Chaney, Schwerner & Goodman Freedom Schools Beginnings Freedom School Curriculum A Different Kind of School The Freedom School in McComb Impact The Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR) Wednesdays in Mississippi The McGhees of Greenwood McComb — Breaking the Klan Siege MFDP Challenge to the Democratic Convention The Plan Building the MFDP Showdown in Atlantic City The Significance of the MFDP Challenge The Political Fallout Some Important Points The Human Cost of Freedom Summer Freedom Summer: The Results Appendices Freedom Summer Project Map Organizational Structure of Freedom Summer Meeting the Freedom Workers The House of Liberty Freedom School Curriculum Units Platform of the Mississippi Freedom School Convention Testimony of Fannie Lou Hamer, Democratic Convention Quotation Sources [Terminology — Various authors use either "Freedom Summer" or "Summer Project" or both interchangeably. This book uses "Summer Project" to refer specifically to the project organized and led by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO). We use "Freedom Summer" to refer to the totality of all Freedom Movement efforts in Mississippi over the summer of 1964, including the efforts of medical, religious, and legal organizations (see Organizational Structure of Freedom Summer for details). -

Twelve Elections That Shaped a Century I Tawdry Populism, Timid Progressivism, 1900-1930

Arkansas Politics in the 20th Century: Twelve Elections That Shaped a Century I Tawdry Populism, Timid Progressivism, 1900-1930 One-gallus Democracy Not with a whimper but a bellow did the 20th century begin in Arkansas. The people’s first political act in the new century was to install in the governor’s office, for six long years, a politician who was described in the most graphic of many colorful epigrams as “a carrot-headed, red-faced, loud-mouthed, strong-limbed, ox-driving mountaineer lawyer that has come to Little Rock to get a reputation — a friend of the fellow who brews forty-rod bug juice back in the mountains.”1 He was the Tribune of the Haybinders, the Wild Ass of the Ozarks, Karl Marx for the Hillbillies, the Stormy Petrel, Messiah of the Rednecks, and King of the Cockleburs. Jeff Davis talked a better populism than he practiced. In three terms, 14 years overall in statewide office, Davis did not leave an indelible mark on the government or the quality of life of the working people whom he extolled and inspired, but he dominated the state thoroughly for 1 This quotation from the Helena Weekly World appears in slightly varied forms in numerous accounts of Davis's yers. It appeared in the newspaper in the spring of 1899 and appears in John Gould Fletcher, Arkansas (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1947) p. 2. This version, which includes the phrase "that has come to Little Rock to get a reputation" appears in Raymond Arsenault, The Wild Ass of the Ozarks: Jeff Davis and the Social Bases of Southern Politics (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984), p. -

Voting Rights in Texas: 1982–2006

VOTING RIGHTS IN TEXAS: 1982–2006 NINA PERALES, LUIS FIGUEROA AND CRISELDA G. RIVAS* INTRODUCTION The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) has been indispensable to guaranteeing minority voters access to the ballot in Texas. Texas has ex- perienced a long history of voting discrimination against its Latino and Af- rican-American citizens dating back to 1845.1 The enactment of the VRA in 1965 began a process of integrating Latinos, African-Americans and, more recently, Asian-Americans into the political structures of Texas. Yet, a review of the minority voting experience in Texas since the 1982 VRA reauthorization indicates that this process remains incomplete. Infringe- ments on minority voting rights persist, and noncompliance with the VRA continues at the state and local level. The VRA has proven to be an essen- tial tool for enhancing minority inclusion in Texas. Texas is home to the second-largest Latino population in the United States, and demographic projections show that by 2040, Latinos will con- stitute the majority of citizens in the state.2 Texas also possesses a growing Asian-American population and an African-American population of more than two million.3 The increasing number of racial and ethnic minority citizens in Texas highlights the need to protect vigilantly the voice and electoral rights of the state’s minority electorate. Section 5 of the VRA, the preclearance requirement, was extended to Texas in 19754 due to the state’s history of excluding Mexican-Americans * Nina Perales, Southwest Regional Counsel for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Edu- cational Fund. Luis Figueroa, Legislative Staff Attorney for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund. -

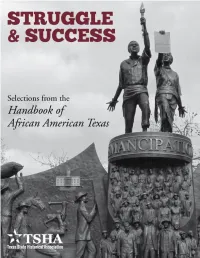

Struggle and Success Page I the Development of an Encyclopedia, Whether Digital Or Print, Is an Inherently Collaborative Process

Cover Image: The Texas African American History Memorial Monument located at the Texas State Capitol, Austin, Texas. Copyright © 2015 by Texas State Historical Association All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions,” at the address below. Texas State Historical Association 3001 Lake Austin Blvd. Suite 3.116 Austin, TX 78703 www.tshaonline.org IMAGE USE DISCLAIMER All copyrighted materials included within the Handbook of Texas Online are in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107 related to Copyright and “Fair Use” for Non-Profit educational institutions, which permits the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA), to utilize copyrighted materials to further scholarship, education, and inform the public. The TSHA makes every effort to conform to the principles of fair use and to comply with copyright law. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Dear Texas History Community, Texas has a special place in history and in the minds of people throughout the world. Texas symbols such as the Alamo, oil wells, and even the shape of the state, as well as the men and women who worked on farms and ranches and who built cities convey a sense of independence, self-reliance, hard work, and courage.