Like a Champion an Olympian’S Approach for Every Runner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Event Winners

Meet History -- NCAA Division I Outdoor Championships Event Winners as of 6/17/2017 4:40:39 PM Men's 100m/100yd Dash 100 Meters 100 Meters 1992 Olapade ADENIKEN SR 22y 292d 10.09 (2.0) +0.09 2017 Christian COLEMAN JR 21y 95.7653 10.04 (-2.1) +0.08 UTEP {3} Austin, Texas Tennessee {6} Eugene, Ore. 1991 Frank FREDERICKS SR 23y 243d 10.03w (5.3) +0.00 2016 Jarrion LAWSON SR 22y 36.7652 10.22 (-2.3) +0.01 BYU Eugene, Ore. Arkansas Eugene, Ore. 1990 Leroy BURRELL SR 23y 102d 9.94w (2.2) +0.25 2015 Andre DE GRASSE JR 20y 215d 9.75w (2.7) +0.13 Houston {4} Durham, N.C. Southern California {8} Eugene, Ore. 1989 Raymond STEWART** SR 24y 78d 9.97w (2.4) +0.12 2014 Trayvon BROMELL FR 18y 339d 9.97 (1.8) +0.05 TCU {2} Provo, Utah Baylor WJR, AJR Eugene, Ore. 1988 Joe DELOACH JR 20y 366d 10.03 (0.4) +0.07 2013 Charles SILMON SR 21y 339d 9.89w (3.2) +0.02 Houston {3} Eugene, Ore. TCU {3} Eugene, Ore. 1987 Raymond STEWART SO 22y 80d 10.14 (0.8) +0.07 2012 Andrew RILEY SR 23y 276d 10.28 (-2.3) +0.00 TCU Baton Rouge, La. Illinois {5} Des Moines, Iowa 1986 Lee MCRAE SO 20y 136d 10.11 (1.4) +0.03 2011 Ngoni MAKUSHA SR 24y 92d 9.89 (1.3) +0.08 Pittsburgh Indianapolis, Ind. Florida State {3} Des Moines, Iowa 1985 Terry SCOTT JR 20y 344d 10.02w (2.9) +0.02 2010 Jeff DEMPS SO 20y 155d 9.96w (2.5) +0.13 Tennessee {3} Austin, Texas Florida {2} Eugene, Ore. -

In This Issue

PROMOTING FITNESS IN BREVARD COUNTY THROUGH RUNNING & WALKING FEBRUARY 2017 IN THIS ISSUE Drama at Disney World Run a Mile with Matt Mahoney Before You Run Again, Identify and Rectify FEBRUARY 2017 SCR/1 SPACECOASTRUNNERS.ORG ESTABLISHED 1978 DEPARTMENTS 05 From the Editor 07 Presidential Ponderings 56 Local Race Calendar 59 Birthday Calendar RESOURCES 03 SCR Board Members 09 Local Fun Runs 24 Member Race Discounts FEATURES 12 SCR Central 27 Run Local On Our Cover: Wolfgang Jensen heads into the chilly last turn of 28 Before You Run Again, Identify the Tooth Trot 5K on January 28th. Photo credit: TriHokie Images and Rectify Above: With over 300 participants racing the new Wickham Park course, the 19th annual Tooth Trot 5K was a smashing success. 33 Runner of the Year Series Shown l to r: Greg Griffin, Hazel McNees, Carol Ball, David Grant and Chris Marriott. Photo credit: TriHokie Images 46 Run A Mile With... 49 Long Distance Relationships SPACE 33K COAST 51 Out-of-Town Race Recap CHALLENGE 54 Where in the World? IS BACK! 57 3 Ways to Rekindle Your Love Don’t miss out! The 33K Space Coast Challenge’s next race is the Eye of the Dragon 10K on February 19. Runners and walkers who have completed the Space Coast Classic 15K and then also com- RACE REPORTS plete this race along with the Space Walk of Fame 8K will receive this unique medal stand (shown above) to commemorate their 36 Tooth Trot 5K running efforts. 38 Color Me Healthy 5K 39 Cops & Robbers 5K SCR Membership Information 40 Fight Child Hunger 5K Renew your annual membership with no extra fees! The website no longer charges any additional online fees. -

The Updated Training Wisdom of John Kellogg

The Updated Training Wisdom of John Kellogg A collection of John Kellogg’s writings on training for distance runners Compiled by John Davis between May 2009 and December 2015 [email protected] www.runningwritings.com “Why do I pose as ‘Oz’? Because I know which mission to assign to help runners discover their potential. But I can't give them any results through magical powers; I'm just a human like the little carnival man from Kansas. I can only guide them. ” —John Kellogg Preface The goal of this project was to compile as many of John Kellogg’s posts on LetsRun.com as possible. I profoundly admire his training advice and his knowledge, and applying his principles to my own training brought me to new heights as a runner. Why John Kellogg, and not any of the other highly-regarded figures in the running world who have posted on LetsRun.com over the years (Renato Canova, Nobby Hashizume, Jack Daniels, et al.)? Perhaps because of his mysterious, guru-like reputation, or perhaps because of the sheer difficulty of assembling the range of posts. I also felt that it had to be done, that it would be a great loss for this knowledge to fade into obscurity over the years. John Kellogg seems to revel in the anonymity of the internet, and has posted under probably dozens of different “handles” over the years. In all likelihood, the writings here represent only a fraction of his total contribution to the online running community. Though his words sometimes fell on deaf ears, the power of the internet preserved much of his writing. -

Long Distance Running Division

2006 Year-End Reports 28th Annual Meeting Reports from the Long Distance Running Division Men’s Long Distance Running Women’s Long Distance Running Masters Long Distance Running Cross Country Council Mountain, Ultra & Trail (MUT) Council Road Running Technical Council 97 National Officers, National Office Staff, Division and Committee Chairs 98 2006 Year-End Reports 28th Annual Meeting Men’s Long Distance Running B. USA National Championships 2005 USA Men's 10 km Championship – Food KEY POINTS World Senior Bowl 10k Mobile, AL – November 5, 2005 Update October 2005 to December 2005 http://www.usatf.org/events/2005/USA10kmCha As last year’s USATF Men’s LDR Annual Report mpionship-Men/ was written in October 2005 in order to meet A dominant display and new course record of publication deadlines for the Annual Convention, 28:11 for Dathan Ritzenhein to become the USA here are a few highlights of Men’s activities from National Champion. October 2005 through to the end of 2005. (Web site links provided where possible.) 2005 USATF National Club Cross Country Championships A. Team USA Events November 19, 2005 Genesee Valley Park - IAAF World Half Marathon Championships – Rochester, NY October 1, 2005, Edmonton, Canada http://www.usatf.org/events/2005/USATFClubX http://www.usatf.org/events/2005/IAAFWorldHalf CChampionships/ MarathonChampionships/ An individual win for Matt Tegenkamp, and Team Scores of 1st Hansons-Brooks D P 50 points th 6 place team United States - 3:11:38 - 2nd Asics Aggie R C 68 points USA Team Leader: Allan Steinfeld 3rd Team XO 121 points th 15 Ryan Shay 1:03:13 th 20 Jason Hartmann 1:03:32 C. -

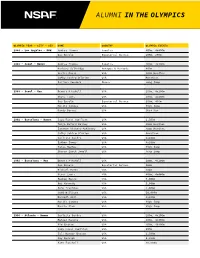

Alumni in the Olympics

ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS 1984 - Los Angeles - M&W Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m, 200m 1988 - Seoul - Women Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Barbara Selkridge Antigua & Barbuda 400m Leslie Maxie USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Juliana Yendork Ghana Long Jump 1988 - Seoul - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 200m, 400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Randy Barnes USA Shot Put 1992 - Barcelona - Women Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 1,500m Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeene Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Carlette Guidry USA 4x100m Esther Jones USA 4x100m Tanya Hughes USA High Jump Sharon Couch-Jewell USA Long Jump 1992 - Barcelona - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m Michael Bates USA 200m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Reuben Reina USA 5,000m Bob Kennedy USA 5,000m John Trautman USA 5,000m Todd Williams USA 10,000m Darnell Hall USA 4x400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Darrin Plab USA High Jump 1996 - Atlanta - Women Carlette Guidry USA 200m, 4x100m Maicel Malone USA 400m, 4x400m Kim Graham USA 400m, 4X400m Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 800m Juli Henner Benson USA 1,500m Amy Rudolph USA 5,000m Kate Fonshell USA 10,000m ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS Ann-Marie Letko USA Marathon Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeen Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Shana Williams -

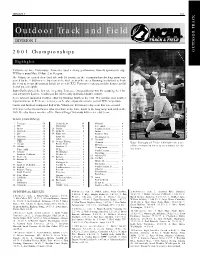

Outdoor Track and Field DIVISION I

DIVISION I 103 Outdoor Track and Field DIVISION I 2001 Championships OUTDOOR TRACK Highlights Volunteers Are Victorious: Tennessee used a strong performance from its sprinters to edge TCU by a point May 30-June 2 at Oregon. The Volunteers earned their third title with 50 points, as the championship-clinching point was scored by the 1,600-meter relay team in the final event of the meet. Knowing it only had to finish the event to secure the point to break the tie with TCU, Tennessee’s unit passed the baton careful- ly and placed eighth. Justin Gatlin played the key role in getting Tennessee into position to win by capturing the 100- and 200-meter dashes. Gatlin was the meet’s only individual double winner. Sean Lambert supported Gatlin’s effort by finishing fourth in the 100. His position was another important factor in Tennessee’s victory, as he placed just ahead of a pair of TCU competitors. Gatlin and Lambert composed half of the Volunteers’ 400-meter relay team that was second. TCU was led by Darvis Patton, who was third in the 200, fourth in the long jump and sixth in the 100. He also was a member of the Horned Frogs’ victorious 400-meter relay team. TEAM STANDINGS 1. Tennessee ..................... 50 Colorado St. ................. 10 Missouri........................ 4 2. TCU.............................. 49 Mississippi .................... 10 N.C. A&T ..................... 4 3. Baylor........................... 361/2 28. Florida .......................... 9 Northwestern St. ........... 4 4. Stanford........................ 36 29. Idaho St. ...................... 8 Purdue .......................... 4 5. LSU .............................. 32 30. Minnesota ..................... 7 Southern Miss. .............. 4 6. Alabama...................... -

Chicago Year-By-Year

YEAR-BY-YEAR CHICAGO MEDCHIIAC INFOAGO & YEFASTAR-BY-Y FACTSEAR TABLE OF CONTENTS YEAR-BY-YEAR HISTORY 2011 Champion and Runner-Up Split Times .................................... 126 2011 Top 25 Overall Finishers ....................................................... 127 2011 Top 10 Masters Finishers ..................................................... 128 2011 Top 5 Wheelchair Finishers ................................................... 129 Chicago Champions (1977-2011) ................................................... 130 Chicago Champions by Country ...................................................... 132 Masters Champions (1977-2011) .................................................. 134 Wheelchair Champions (1984-2011) .............................................. 136 Top 10 Overall Finishers (1977-2011) ............................................. 138 Historic Event Statistics ................................................................. 161 Historic Weather Conditions ........................................................... 162 Year-by-Year Race Summary............................................................ 164 125 2011 CHAMPION/RUNNER-UP SPLIT TIMES 2011 TOP 25 OVERALL FINISHERS 2011 CHAMPION AND RUNNER-UP SPLIT TIMES 2011 TOP 25 OVERALL FINISHERS MEN MEN Moses Mosop (KEN) Wesley Korir (KEN) # Name Age Country Time Distance Time (5K split) Min/Mile/5K Time Sec. Back 1. Moses Mosop ..................26 .........KEN .................................... 2:05:37 5K .................00:14:54 .....................04:47 -

2011 Ucla Men's Track & Field

2011 MEN’S TRACK & FIELD SCHEDULE IINDOORNDOOR SSEASONEASON Date Meet Location January 28-29 at UW Invitational Seattle, WA February 4-5 at New Balance Collegiate Invitational New York, NY at New Mexico Classic Albuquerque, NM February 11-12 at Husky Classic Seattle, WA February 25-26 at MPSF Indoor Championships Seattle, WA March 5 at UW Final Qualifi er Seattle, WA March 11-12 at NCAA Indoor Championships College Station, TX OOUTDOORUTDOOR SSEASONEASON Date Meet Location March 11-12 at Northridge Invitational Northridge, CA March 18-19 at Aztec Invitational San Diego, CA March 25 vs. Texas & Arkansas Austin, TX April 2 vs. Tennessee ** Drake Stadium April 7-9 Rafer Johnson/Jackie Joyner Kersee Invitational ** Drake Stadium April 14 at Mt. SAC Relays Walnut, CA April 17 vs. Oregon ** Drake Stadium April 22-23 at Triton Invitational La Jolla, CA May 1 at USC Los Angeles, CA May 6-7 at Pac-10 Multi-Event Championships Tucson, AZ May 7 at Oxy Invitational Eagle Rock, CA May 13-14 at Pac-10 Championships Tucson, AZ May 26-27 at NCAA Preliminary Round Eugene, OR June 8-11 at NCAA Outdoor Championships Des Moines, IA ** denotes UCLA home meet TABLE OF CONTENTS/QUICK FACTS QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Location .............................................................................J.D. Morgan Center, GENERAL INFORMATION ..........................................325 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, CA, 90095 2011 Schedule .........................Inside Front Cover Athletics Phone ......................................................................(310) -

2016TN02 Mlist

Volume 15, No. 02 January 06, 2016 version i — 2015 U.S. Men’s Lists — KEY TO LISTS compiled by Glen McMicken These lists give the top 40 U.S. performers (and top 10 per- formances, denoted by a ——) of the 2015 season, with an appending of those foreign collegians whose marks fall into 100 METERS that range. In the wind-aided category, the domestics and 9.74 ............ Justin Gatlin (Nike) .................. 5/15 ............. Doha DL foreign collegians are commingled (' after name = foreigner 9.75 ............ ——Gatlin ................................ 6/04 ............ Rome DL on windy list). Relay teams may contain non-U.S. nationals. ................... ——Gatlin ................................ 7/09 ...... Lausanne DL 9.77 ............ ——Gatlin ................................ 8/23 ............ World Ch Athletes who change nationality during the season are listed 9.78 ............ ——Gatlin ................................ 7/17 .........Monaco DL with their nationality as of the date of the mark, so marks 9.80 ............ ——Gatlin ................................ 8/23 ............ World Ch here may not be their actual best of the year. 9.84 ............ **Trayvon Bromell (Bay) ........... 6/25 ................ USATF Open athletes and high schoolers have no notation before 9.86 ............ Mike Rodgers (Nike) ................ 8/23 ............ World Ch their name. Collegians are noted by class: - = senior; * = 9.87 ............ Tyson Gay (Nike) ..................... 6/26 ................ USATF junior; **=soph; *** = frosh. 9.88 ............ ——Gay................................... 5/30 ..........Eugene DL (A) = altitude over 1000m (in affected events only). Wind-aided ................... ——Rodgers ........................... 7/11 ........ Madrid IWC marks are those of greater than 2.0mps. Windy marks are **11 performances by 4 performers** listed only if superior to the best legal mark (windy perfor- 9.93 ............ Ryan Bailey (Nike) ................... 5/09 ..... Kingston IWC mances listed to level of legal performances). -

A Star Is Born Shalane Flanagan finds Her Distance

A Star Is Born Shalane Flanagan finds her distance. BY TITO MORALES hortly after Shalane Flanagan’s marathon debut in New York City, she and her husband, Steve Edwards, boarded a plane for a trip to the Hawaiian SIslands. A few teammates from the Oregon Track Club—Simon Bairu, Tim Nelson, and Lisa Koll—joined them on the getaway. As Flanagan lounged and recuperated on a remote beach in Maui, some 5,000 miles from Manhattan’s Central Park, a couple of tourists approached and gushed, “Oh, you’re that girl who ran the marathon! Congratulations!” “I was literally in a bathing suit, hat, and sunglasses,” Flanagan recalls with a laugh. “I was kind of shocked that they would recognize me.” She shouldn’t have been. While her bronze medal in the 10,000 meters at the 2008 Olympic Games may have made her a star in the eyes of the international running community, it was her scintillating run at one of the highest-profile road races on the planet that elevated her renown to just about everyone else. The runners’ daughter goes long As was detailed in “The Runners’ Daughter” [see the Sept/Oct 2010 issue], Flana- gan’s transformation into a bona fide marathoner was a long time coming. The seed was planted during a childhood spent in Marblehead, Massachusetts. Patri- ots’ Day meant an annual excursion into the city to watch the Boston Marathon. She learned early on of her parents’ exploits as distance runners, and she vividly remembers watching her father compete along the famed Boston course. -

Us Olympic Trials

7M 8M BIRMINGHAM, AL US OLYMPIC TRIALS - MEN'S MARATHON 7 FEBRUARY, 2004 Unexpectedly for a Trials Marathon, the three favorites came through as Alan Culpepper won a thrilling race - sprinting away from Meb Keflezighi in the final 200 meters, with Dan Browne claiming the third spot on the Athens 5.5 Mi. BIRMINGHAM LOOP Sean Hartnett for Track & Field News Olympic Team. The race followed an unpredictable script after the pack managed only 5:15 pace for the first 3 miles. Brian Sell Teddy Mitchel and Brian Sell broke from the pack, and after 7 miles Sell surged away alone building a minute lead at sets sail at Project Support Provided by 16 miles. The 15 man chase pack began to chase after Sell, and after Culpepper through in a 4:47 18th mile only 5:00 pace Meb, Browne, and Trent Briney remained in the hunt. The pack blew past Sell at 21.5 miles and Briney soon fell off University of Wisconsin - Eau Claire the pace. Browne ran into difficulties a mile later as Culpepper and P P 5:03 Keflezighi matched strides and wits over the final miles, 5:09 5:09 5:10 5:11 5 6 7 8 9 P After averaging before Culpepper sprinted to 5:11 pace for the 5:02 5:00 5:04 victory. 4 5:02 5:02 4:54 4:53 first 7 miles, the 5:12 5:03 fifteen runners 5:13 3 18M 10 2 4:57 STARTING SEGMENT MILES 1-9 in the chase pack hit 5:02 5:12 5:13 5:02 pace for the 8 5:13 13 12 miles between 7 5:01 and 15. -

Oly Roster CA-PA

2012 Team USA Olympic Roster (including Californians and Pacific Association/USATF athletes) (Compiled by Mark Winitz) Key Blue type indicates California residents, or athletes with strong California ties Green type indicates Californians who are Pacific Association/USATF members, or athletes with strong Pacific Association ties Bold type indicates past World Outdoor or Olympic individual medalist * Relay pools are composed of the 100m and 400m rosters, the athletes listed in each pool, plus any athlete already on the roster in any other event * All nominations are pending approval by the USOC board of directors. MEN 100m – Justin Gatlin (Orlando, Fla.), Tyson Gay (Clermont, Fla.), Ryan Bailey (Salem, Ore.) 200m – Wallace Spearmon (Dallas, Texas), Maurice Mitchell (Tallahassee, Fla.), Isiah Young (Lafayette, Miss.) 400m – LaShawn Merritt (Suffolk, Va.), Tony McQuay (Gainesville, Fla.), Bryshon Nellum (Los Angeles, Calif.) 800m – Nick Symmonds (Springfield, Ore.), Khadevis Robinson (Las Vegas, Nev.; former longtime Los Angeles-area resident), Duane Solomon (Los Angeles, Calif.) 1500 m– Leonel Manzano (Austin, Texas), Matthew Centrowitz (Eugene, Ore.), Andrew Whetting (Eugene, Ore.) 3000m Steeplechase – Evan Jager (Portland, Ore.), Donn Cabral (Conn.), Kyle Alcorn (Mesa, Ariz.; Buchanan H.S. /Clovis, Calif. '03) 5000m – Galen Rupp (Portland, Ore.), Bernard Lagat (Tucson, Ariz.), Lopez Lomong (Beaverton, Ore.) 10,000m – Galen Rupp (Portland, Ore.), Matt Tegenkamp (Portland, Ore.), Dathan Ritzenhein (Portland, Ore.) 20 km Race Walk – Trevor