A Star Is Born Shalane Flanagan finds Her Distance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue

PROMOTING FITNESS IN BREVARD COUNTY THROUGH RUNNING & WALKING FEBRUARY 2017 IN THIS ISSUE Drama at Disney World Run a Mile with Matt Mahoney Before You Run Again, Identify and Rectify FEBRUARY 2017 SCR/1 SPACECOASTRUNNERS.ORG ESTABLISHED 1978 DEPARTMENTS 05 From the Editor 07 Presidential Ponderings 56 Local Race Calendar 59 Birthday Calendar RESOURCES 03 SCR Board Members 09 Local Fun Runs 24 Member Race Discounts FEATURES 12 SCR Central 27 Run Local On Our Cover: Wolfgang Jensen heads into the chilly last turn of 28 Before You Run Again, Identify the Tooth Trot 5K on January 28th. Photo credit: TriHokie Images and Rectify Above: With over 300 participants racing the new Wickham Park course, the 19th annual Tooth Trot 5K was a smashing success. 33 Runner of the Year Series Shown l to r: Greg Griffin, Hazel McNees, Carol Ball, David Grant and Chris Marriott. Photo credit: TriHokie Images 46 Run A Mile With... 49 Long Distance Relationships SPACE 33K COAST 51 Out-of-Town Race Recap CHALLENGE 54 Where in the World? IS BACK! 57 3 Ways to Rekindle Your Love Don’t miss out! The 33K Space Coast Challenge’s next race is the Eye of the Dragon 10K on February 19. Runners and walkers who have completed the Space Coast Classic 15K and then also com- RACE REPORTS plete this race along with the Space Walk of Fame 8K will receive this unique medal stand (shown above) to commemorate their 36 Tooth Trot 5K running efforts. 38 Color Me Healthy 5K 39 Cops & Robbers 5K SCR Membership Information 40 Fight Child Hunger 5K Renew your annual membership with no extra fees! The website no longer charges any additional online fees. -

Seagate Crystal Reports

Flash Results, Inc. Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 10:25 PM 5/24/2012 Page 1 NCAA Division I 2012 Outdoor Track & Field Championships -East Preliminary University of North Florida - 5/24/2012 to 5/26/2012 Results Women 100 Meter Dash Women 400 Meter Dash American: 10.49 A7/16/1988 Florence Griffith Joyner American: 48.70 A9/17/2006 Sanya Richards College Best: 10.78 C6/3/1989 Dawn Sowell College Best: 50.10 C6/11/2005 Monique Henderson NCAA Meet: 10.786/3/1989 Dawn Sowell NCAA Meet: 50.106/11/2005 Monique Henderson Name Yr School Prelims Name Yr School Prelims Preliminaries Preliminaries 1 Aurieyall Scott SO UCF 11.25Q0.9 1 Marlena Wesh JR Clemson 52.46Q 2 Octavious Freeman FR UCF 11.29Q0.6 2 Lanie Whittaker SO Florida 52.46Q 3 Kimberlyn Duncan JR LSU 11.35Q-1.5 3 Rebecca Alexander SR LSU 52.70Q 4 Tori Bowie SR So. Mississippi 11.45Q1.4 4 Jody-Ann Muir JR Miss State 52.74Q 5 Semoy Hackett SR LSU 11.46Q-0.6 5 Lenora Guion-Firmin JR MD-Eastern 52.76Q 6 Chelsea Hayes SR Louisiana Tech 11.56Q-1.5 6 Brianna Frazier SO NorthShore Florida 52.86Q 7 Kai Selvon SO Auburn 11.41Q0.6 7 Jonique Day SR LSU 52.83Q 8 Alexis Love JR Murray State 11.47Q1.4 8 Amara Jones SR Savannah State 52.93Q 9 Cambrya Jones SR Pittsburgh 11.47Q0.9 9 CeCe Williams SR Auburn 52.95Q 10 Sheila Paul SR UCF 11.66Q-1.5 10 Kristin Bridges SR Mississippi 53.27Q 11 Monique Gracia SR Clemson 11.69Q-1.5 11 Shaniqua McGinnis SR Ohio State 53.31Q 12 Flings Owusu-Agyapong SR Syracuse 11.77Q-0.6 12 Cierra McGee JR George Mason 53.32Q 13 Gabrielle Houston SR Charleston South 11.45Q0.6 13 Christie -

Long Distance Running Division

2006 Year-End Reports 28th Annual Meeting Reports from the Long Distance Running Division Men’s Long Distance Running Women’s Long Distance Running Masters Long Distance Running Cross Country Council Mountain, Ultra & Trail (MUT) Council Road Running Technical Council 97 National Officers, National Office Staff, Division and Committee Chairs 98 2006 Year-End Reports 28th Annual Meeting Men’s Long Distance Running B. USA National Championships 2005 USA Men's 10 km Championship – Food KEY POINTS World Senior Bowl 10k Mobile, AL – November 5, 2005 Update October 2005 to December 2005 http://www.usatf.org/events/2005/USA10kmCha As last year’s USATF Men’s LDR Annual Report mpionship-Men/ was written in October 2005 in order to meet A dominant display and new course record of publication deadlines for the Annual Convention, 28:11 for Dathan Ritzenhein to become the USA here are a few highlights of Men’s activities from National Champion. October 2005 through to the end of 2005. (Web site links provided where possible.) 2005 USATF National Club Cross Country Championships A. Team USA Events November 19, 2005 Genesee Valley Park - IAAF World Half Marathon Championships – Rochester, NY October 1, 2005, Edmonton, Canada http://www.usatf.org/events/2005/USATFClubX http://www.usatf.org/events/2005/IAAFWorldHalf CChampionships/ MarathonChampionships/ An individual win for Matt Tegenkamp, and Team Scores of 1st Hansons-Brooks D P 50 points th 6 place team United States - 3:11:38 - 2nd Asics Aggie R C 68 points USA Team Leader: Allan Steinfeld 3rd Team XO 121 points th 15 Ryan Shay 1:03:13 th 20 Jason Hartmann 1:03:32 C. -

Badger Badgers Celebrate Four National Championships in 2005-06

Badger2005–06 Badgers Celebrate Four National Athletics Diary Championships in 2005-06 August 2005—The open house for the newly renovated Camp Randall Stadium is “What a great year for Badger held. Athletics,” were the words of Director September 2005—The Badgers celebrate of Athletics Barry Alvarez after the grand re-opening of Camp Randall Wisconsin won three NCAA champi- Stadium with a win over Bowling Green onships in 2005–06. The Badgers also State. The celebration also includes one of the added a national title by the women’s largest football reunions ever ... Seven former lightweight rowing team and three Badgers are inducted into the UW Athletics individual national championships. Hall of Fame ... UW football fans raise nearly $60,000 for Hurricane Katrina relief ᮣ The men's cross country won its October 2005—UW CHAMPS program is fourth national title in program Men’s Cross Country recognized as a Program of Excellence by the history in November. Senior Simon Athletic Directors’ Association ... Deputy Bairu won his second consecutive individual title. Athletic Director Jamie Pollard is named the athletic director at Iowa State ... The Kellner ᮣ The women’s hockey team won its Club in the Kohl Center opens first NCAA title. It was just the second November 2005—The NCAA post-season appearance and UW men’s cross country first run at the Frozen Four for the Badgers. team wins its fourth NCAA championship and ᮣ Wisconsin became the first school senior Simon Bairu wins in NCAA history to win both the his second consecutive women’s and men’s ice hockey cham- individual title .. -

MEDIA INFO & Fast Facts

MEDIAWELCOME INFO MEDIA INFO Media Info & FAST FacTS Media Schedule of Events .........................................................................................................................................4 Fact Sheet ..................................................................................................................................................................6 Prize Purses ...............................................................................................................................................................8 By the Numbers .........................................................................................................................................................9 Runner Pace Chart ..................................................................................................................................................10 Finishers by Year, Gender ........................................................................................................................................11 Race Day Temperatures ..........................................................................................................................................12 ChevronHoustonMarathon.com 3 MEDIA INFO Media Schedule of Events Race Week Press Headquarters George R. Brown Convention Center (GRB) Hall D, Third Floor 1001 Avenida de las Americas, Downtown Houston, 77010 Phone: 713-853-8407 (during hours of operation only Jan. 11-15) Email: [email protected] Twitter: @HMCPressCenter -

2005 Canadian XC Champs: Junior Women's Results

Championnat canadien de cross-country 2005 2005 Canadian Cross Country Championships Vancouver, BC 3 December Official Results/Resultats Officiels Junior Women/Femmes Junior 5,000m PLACE NO. NAME YB CITY PR CLUB TIME PACE CLUB/TEAM PROV/TEAM ===== ==== ====================== == ============= == ===== ======= ===== ============================= ============================= 1 209 Kate Van Buskirk 87 Brampton ON Missi 17:28 5:38 2 523 Anita Campbell 87 Abbotsford BC Valle 17:37 5:41 Valley Royals A 3 455 Tarah McKay 87 St. Clements ON Tri C 17:43 5:43 4 217 Sheila Reid 89 Newmarket ON Newma 17:47 5:44 5 448 Lindsay Carson 89 Cambridge ON Tri C 17:49 5:45 6 433 Mandy McBean 87 Toronto ON Toron 17:51 5:45 Toronto Olympic 7 257 Danelle Woods 89 Ottawa ON Ottaw 17:54 5:46 Ottawa Lions 8 412 Rachel Cliff 88 Vancouver BC Team 18:01 5:48 BC Athletics Gold 9 548 Stephanie Smith 90 Aurora ON York 18:01 5:48 10 541 Jacqueline Malette 86 Windsor ON Winds 18:05 5:50 11 246 Jennifer Biewald 88 Ottawa ON Ottaw 18:06 5:50 Ottawa Lions 12 349 Kristen Kolstad 86 Surrey BC SFU 18:08 5:51 13 300 Karissa Le Page 91 Regina SK Queen 18:10 5:51 Saskatchewan Athletics Gold 14 59 Sarah-Anne Brault 89 Winnipeg MB Colle 18:12 5:52 15 411 Angela Shaw 89 Langley BC Team 18:13 5:52 Valley Royals A BC Athletics Gold 16 311 Jayne Grebinski 88 Regina SK Regin 18:20 5:54 Regina Harriers Team A Saskatchewan Athletics Gold 17 34 Ciara Kary 92 Calgary AB Calga 18:20 5:54 Calgary Spartans TC A Alberta Gold 18 480 Justine Johnson 91 Victoria BC Unatt 18:24 5:56 19 13 Kali Burt -

Indoor Track and Field DIVISION I Women’S

Indoor Track and Field DIVISION I WOMEN’S Highlights Lady Vols show world-class distance dominance: Tennessee dominated Division I women’s indoor track March 13-14 – and dominated the world for more than 10 minutes. The Lady Vols captured the school’s second team title in five years at the Division I Women’s Indoor Track and Field Championships and won two events during competition at Texas A&M – including a victory in world-record time in the distance medley relay. Tennessee’s time of 10 minutes, 50.98 seconds, in that event sliced more than three seconds off Villanova’s 21-year-old world mark in the 1,200-/400-/800-/1,600-meter medley, and eight seconds off UCLA’s 2002 meet record. The relay squad was anchored for the second straight year by Sarah Bowman, who figured in both Lady Vols’ event titles and collected a second meet record when she out- leaned Texas Tech’s Sally Kipyego to win the mile run. “Oh, my gosh, look at what we’ve done this weekend,” said Bowman, who also was a member of the 2005 indoor championship team. “I couldn’t ask for a sweeter weekend my senior year. I can’t even put it into words. It’s so amazing. “The heart that this team has, I could actually tear up just talking about them. Just to be out here with these girls who are putting their hearts on the line for the team, and it makes you want to do it all the more. It’s awesome to be part of a team like that.” Tennessee coach J.J. -

Good Morning Everyone and Welcome to the Massachusetts State Track Coaches

Good morning everyone and welcome to the Massachusetts State Track Coaches Association’s induction ceremony of former cross country and track and field greats from Massachusetts. These athletes, when competing in high school, in college or beyond, established themselves amongst the best that this state, this country and even this world has ever seen. My name is Bob L’Homme and I coach both the Cross Country and Track and Field teams at Bishop Feehan High School in Attleboro, Ma. And on behalf of the Hall of Fame Committee, Chuck Martin, Jayson Sylvain, Tim Cimeno and Mike Glennon I’d like to thank you all for attending. I am the chairman of the Hall of Fame Committee and I will be your MC for this morning’s induction ceremony. The state of Massachusetts currently has approximately 100 athletes that have been inducted into the Hall of Fame. Names like Johnny Kelley, Billy Squires, John Thomas, Alberto Salazar, Lynn Jennings, Mark Coogan, Calvin Davis, and Shalane Flanagan to name a few are sprinkled within those 100 athletes. Last year we inducted Abby D’Agostino from Masconomet High School, Fred Lewis from Springfield Tech, Karim Ben Saunders from Cambridge R&L, Anne Jennings of Falmouth, Arantxa King of Medford, Ron Wayne of Brockton and Heather Oldham of Woburn H.S. All of these past inductees were your high school league champions, divisional champions, state champions, New England champions, Division 1, 2 and 3 collegiate champions and High School and collegiate All Americans. There are United States Champions, Pan Am Champions, World Champions and Olympic Champions. -

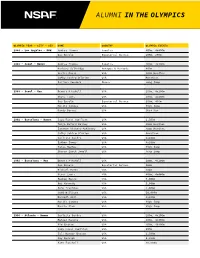

Alumni in the Olympics

ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS 1984 - Los Angeles - M&W Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m, 200m 1988 - Seoul - Women Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Barbara Selkridge Antigua & Barbuda 400m Leslie Maxie USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Juliana Yendork Ghana Long Jump 1988 - Seoul - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 200m, 400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Randy Barnes USA Shot Put 1992 - Barcelona - Women Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 1,500m Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeene Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Carlette Guidry USA 4x100m Esther Jones USA 4x100m Tanya Hughes USA High Jump Sharon Couch-Jewell USA Long Jump 1992 - Barcelona - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m Michael Bates USA 200m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Reuben Reina USA 5,000m Bob Kennedy USA 5,000m John Trautman USA 5,000m Todd Williams USA 10,000m Darnell Hall USA 4x400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Darrin Plab USA High Jump 1996 - Atlanta - Women Carlette Guidry USA 200m, 4x100m Maicel Malone USA 400m, 4x400m Kim Graham USA 400m, 4X400m Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 800m Juli Henner Benson USA 1,500m Amy Rudolph USA 5,000m Kate Fonshell USA 10,000m ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS Ann-Marie Letko USA Marathon Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeen Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Shana Williams -

2011 Ucla Men's Track & Field

2011 MEN’S TRACK & FIELD SCHEDULE IINDOORNDOOR SSEASONEASON Date Meet Location January 28-29 at UW Invitational Seattle, WA February 4-5 at New Balance Collegiate Invitational New York, NY at New Mexico Classic Albuquerque, NM February 11-12 at Husky Classic Seattle, WA February 25-26 at MPSF Indoor Championships Seattle, WA March 5 at UW Final Qualifi er Seattle, WA March 11-12 at NCAA Indoor Championships College Station, TX OOUTDOORUTDOOR SSEASONEASON Date Meet Location March 11-12 at Northridge Invitational Northridge, CA March 18-19 at Aztec Invitational San Diego, CA March 25 vs. Texas & Arkansas Austin, TX April 2 vs. Tennessee ** Drake Stadium April 7-9 Rafer Johnson/Jackie Joyner Kersee Invitational ** Drake Stadium April 14 at Mt. SAC Relays Walnut, CA April 17 vs. Oregon ** Drake Stadium April 22-23 at Triton Invitational La Jolla, CA May 1 at USC Los Angeles, CA May 6-7 at Pac-10 Multi-Event Championships Tucson, AZ May 7 at Oxy Invitational Eagle Rock, CA May 13-14 at Pac-10 Championships Tucson, AZ May 26-27 at NCAA Preliminary Round Eugene, OR June 8-11 at NCAA Outdoor Championships Des Moines, IA ** denotes UCLA home meet TABLE OF CONTENTS/QUICK FACTS QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Location .............................................................................J.D. Morgan Center, GENERAL INFORMATION ..........................................325 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, CA, 90095 2011 Schedule .........................Inside Front Cover Athletics Phone ......................................................................(310) -

Teen Sensation Athing Mu

• ALL THE BEST IN RUNNING, JUMPING & THROWING • www.trackandfieldnews.com MAY 2021 The U.S. Outdoor Season Explodes Athing Mu Sets Collegiate 800 Record American Records For DeAnna Price & Keturah Orji T&FN Interview: Shalane Flanagan Special Focus: U.S. Women’s 5000 Scene Hayward Field Finally Makes Its Debut NCAA Formchart Faves: Teen LSU Men, USC Women Sensation Athing Mu Track & Field News The Bible Of The Sport Since 1948 AA WorldWorld Founded by Bert & Cordner Nelson E. GARRY HILL — Editor JANET VITU — Publisher EDITORIAL STAFF Sieg Lindstrom ................. Managing Editor Jeff Hollobaugh ................. Associate Editor BUSINESS STAFF Ed Fox ............................ Publisher Emeritus Wallace Dere ........................Office Manager Teresa Tam ..................................Art Director WORLD RANKINGS COMPILERS Jonathan Berenbom, Richard Hymans, Dave Johnson, Nejat Kök SENIOR EDITORS Bob Bowman (Walking), Roy Conrad (Special AwaitsAwaits You.You. Projects), Bob Hersh (Eastern), Mike Kennedy (HS Girls), Glen McMicken (Lists), Walt Murphy T&FN has operated popular sports tours since 1952 and has (Relays), Jim Rorick (Stats), Jack Shepard (HS Boys) taken more than 22,000 fans to 60 countries on five continents. U.S. CORRESPONDENTS Join us for one (or more) of these great upcoming trips. John Auka, Bob Bettwy, Bret Bloomquist, Tom Casacky, Gene Cherry, Keith Conning, Cheryl Davis, Elliott Denman, Peter Diamond, Charles Fleishman, John Gillespie, Rich Gonzalez, Ed Gordon, Ben Hall, Sean Hartnett, Mike Hubbard, ■ 2022 The U.S. Nationals/World Champion- ■ World Track2023 & Field Championships, Dave Hunter, Tom Jennings, Roger Jennings, Tom ship Trials. Dates and site to be determined, Budapest, Hungary. The 19th edition of the Jordan, Kim Koffman, Don Kopriva, Dan Lilot, but probably Eugene in late June. -

USATF Cross Country Championships Media Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS NATIONAL CHAMPIONS LIST..................................................................................................................... 2 NCAA DIVISION I CHAMPIONS LIST .......................................................................................................... 7 U.S. INTERNATIONAL CROSS COUNTRY TRIALS ........................................................................................ 9 HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS ........................................................................................ 20 APPENDIX A – 2009 USATF CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS ............................................... 62 APPENDIX B –2009 USATF CLUB NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS .................................................. 70 USATF MISSION STATEMENT The mission of USATF is to foster sustained competitive excellence, interest, and participation in the sports of track & field, long distance running, and race walking CREDITS The 30th annual U.S. Cross Country Handbook is an official publication of USA Track & Field. ©2011 USA Track & Field, 132 E. Washington St., Suite 800, Indianapolis, IN 46204 317-261-0500; www.usatf.org 2011 U.S. Cross Country Handbook • 1 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS USA Track & Field MEN: Year Champion Team Champion-score 1954 Gordon McKenzie New York AC-45 1890 William Day Prospect Harriers-41 1955 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-28 1891 M. Kennedy Prospect Harriers-21 1956 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-46 1892 Edward Carter Suburban Harriers-41 1957 John Macy New York AC-45 1893-96 Not Contested 1958 John Macy New York AC-28 1897 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-31 1959 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-30 1898 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-42 1960 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-33 1899-1900 Not Contested 1961 Bruce Kidd Houston TFC-35 1901 Jerry Pierce Pastime AC-20 1962 Pete McArdle Los Angeles TC-40 1902 Not Contested 1963 Bruce Kidd Los Angeles TC-47 1903 John Joyce New York AC-21 1964 Dave Ellis Los Angeles TC-29 1904 Not Contested 1965 Ron Larrieu Toronto Olympic Club-40 1905 W.J.