Arxiv:1901.06935V4 [Cs.CR] 16 Mar 2020 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHIELDING and GROUNDING in LARGE DETECTORS* Veljko Radeka Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY 11973-5000 ([email protected])

SHIELDING AND GROUNDING IN LARGE DETECTORS* Veljko Radeka Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY 11973-5000 ([email protected]) Abstract Coupler: Shield (“Faraday cage”) Shielding effectiveness as a function of shield thick- ness and conductivity vs the type and frequency of the interference field is described. Noise induced in trans- mission lines by ground loop driven currents in the shield is evaluated and the importance of low shield resistance is emphasized. Some measures for preven- Cable shield connected to detector shield at the penetration: tion of ground loops and isolation of detector-readout systems are discussed. Detector Counting Area Signal, Low V, ferrite 1. INTRODUCTION High V, control lines core Prevention of electromagnetic interference (EMI), or “noise pickup”, is an important design aspect in large detectors in accelerator environments. It is of particu- ~ 5 50 m lar concern in detector subsystems where signals have insulate ac a large dynamic range or where high accuracy position electrically! power “1” interpolation is performed. Calorimeters are very sen- vacuum pumps, cooling water sitive to coherent noise induced in groups of readout cryo lines, mechanical supports channels where energy sums are formed, covering a “Solid ground” ( “earth” ) large dynamic range. There are several potential noise sources and means of transmission: ac power “2” 1) Noise from digital circuits generated locally on a major ground loops (global) single front end read-out board on the detector; (low impedance) 2) electromagnetic radiation in the space around the Figure 1. An illustration of shielding and ground loop detector generated by other detector subsystems, control concepts. power supplies, silicon-controlled rectifiers, ma- chinery, etc.; Figure 1 illustrates some of the basics of shielding 3) noise induced by penetrations into the detector en- and ground loop control. -

Lab 1: Electric Charge

LAB 1: ELECTRIC CHARGE Equipment List: Electrometer (ES-9078A) Charge producers (ES-9057B) - the wands with dark and white disks on the ends Proof plane - wand with aluminum coated disk on the end Faraday ice pail (ES-9042A) Signal input cable for electrometer - has two alligator clips Black banana lead - grounding cable for electrometer DC power supply (Pasco) - only used for ground port Three prong power cable - for DC power supply Purpose: To explore charge, charge transfer, and charge conservation. Introduction: As with all experiments in this course, please proceed with caution. If you are ever uncertain, please ask for advice. If your equipment starts emitting a continuous beeping sound, disconnect it immediately and ask for help. For many experiments, including the electrostatic charge experiments, there are only a few sets of equipment which are used by many classes. If the equipment is broken, it will affect many other students and it will not be possible to replace it for some time because it is expensive. Please use the equipment with care. In this lab you will create a charge imbalance on the charge producers and use the Faraday ice pail and electrometer to measure this charge. Make sure to answer the questions posed in this lab in your lab book. The Faraday ice pail is a double layer Faraday cage. (Michael Faraday used a metal ice bucket in his original experiment.) When a charged object is placed inside the inner cage, free charge flows within the wires of the inner cage to neutralize this charge on the inside surface of the cage, leaving a residual charge on the outside of the inner cage that is equal to the charge placed inside the cage. -

Development and First Experimental Tests of Faraday Cup Array

REVIEW OF SCIENTIFIC INSTRUMENTS 85, 013302 (2014) Development and first experimental tests of Faraday cup array J. Prokupek, ˚ 1,2,3,a) J. Kaufman,2 D. Margarone,1 M. Kr˚us,1,2,3 A. Velyhan,1 J. Krása,1 T. Burris-Mog,4 S. Busold,5 O. Deppert,5 T. E. Cowan,4,6 and G. Korn1 1Institute of Physics of the AS CR, v. v. i., ELI-Beamlines Project, Na Slovance 2, 182 21 Prague 8, Czech Republic 2Faculty of Nuclear Sciences and Physical Engineering, Czech Technical University in Prague, Bˇrehová 7, 115 19 Prague 1, Czech Republic 3Institute of Plasma Physics of the AS CR, v. v. i./PALS Centre, Za Slovankou 3, 182 00 Prague 8, Czech Republic 4Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR), Bautzner Landstraße 400, D-01328 Dresden, Germany 5Technische Universität Darmstadt (TUD), Schlossgartenstraße 9, D-64289 Darmstadt, Germany 6Technische Universität Dresden, D-01069 Dresden, Germany (Received 29 October 2013; accepted 14 December 2013; published online 9 January 2014) A new type of Faraday cup, capable of detecting high energy charged particles produced in a high intensity laser-matter interaction environment, has recently been developed and demonstrated as a real-time detector based on the time-of-flight technique. An array of these Faraday cups was de- signed and constructed to cover different observation angles with respect to the target normal direc- tion. Thus, it allows reconstruction of the spatial distribution of ion current density in the subcritical plasma region and the ability to visualise its time evolution through time-of-flight measurements, which cannot be achieved with standard laser optical interferometry. -

Troubleshooting Noise in an Electrochemical System with A

Document #: DRK10039 (REV001 | JUN 2017) Troubleshooting Noise in an Electrochemical System with a Rotator This document describes several common sources of electrical noise in an electrochemical rotator system and methods that can be used to reduce the noise. 1. Overview Electrical noise is a common problem for researchers working with rotating electrodes. The following document details frequent noise sources and the steps to take to reduce noise in an electrochemical rotator system. Unfortunately, noise is often difficult to trace and eliminate since it can originate from many different sources. Therefore, even after implementing all of the steps detailed here, noise may still remain because of additional factors, such as lab infrastructure or interference from other instruments. In cases that the noise cannot be reduced to an acceptable level, the ultimate step may be to enclose the rotator system in a Faraday cage. 2. Common Sources of Electrochemical Noise 2.1 Reference Electrode In order for a potentiostat to function properly, there must be adequate ionic conductance between the electrolyte and the reference electrode. Otherwise, the potentiostat may measure a noisy signal. For proper ionic conductance, the reference electrode must 1) maintain good contact with the sample electrolyte in an electrochemical cell and 2) have a low impedance connection. 2.1.1 Proper Electrolyte Contact Good ionic conductance through the reference electrode requires that there are electrolytes present both inside and outside of the frit compartment. Often, poor contact is caused by a gas bubble trapped near the reference electrode’s fritted tip. The bubble disrupts ionic conductance between the reference electrode’s internal electrolyte and the outside sample electrolyte, thereby creating high impedance and noise. -

Is Feynman's Analysis of Electrostatic Screening Correct?

Is Feynman’s Analysis of Electrostatic Screening Correct? Kris Subbarao1 Sukhbir Mahajan2 Abstract In a recent paper on electrostatic shielding, Chapman, Hewett and Trefethen present arguments that the analysis of this effect by Feynman is incorrect. Feynman analyzed shielding by a row of infinitesimally thin wires. They claim that Feynman used the wrong boundary condition invalidating his analysis. In this paper we emphasize that Feynman’s solution is a Green’s function through which behavior of the potential due to finite thickness wires of arbitrary cross-section with appropriate boundary condition can be understood. This shows that the main conclusions of Feynman’s treatment are indeed correct. The configuration analyzed by Maxwell of parallel plates with one of the plates replaced by a row of wires provides a more intuitive understanding of Feynman’s argument. The case of a finite number of wires arranged in a ring (not treated by Feynman), as model of Faraday cage, is different. The structure of the solution in radial coordinates already suggests that one should not expect exponential behavior and further analysis confirms this. There appear to be contradictory results in the literature for its screening behavior in the presence of external charges/fields. 1 KrisSubbarao at gmail.com 2 Mahajans at csus.edu 1. INTRODUCTION In a recent article on Faraday cage effect, Chapman, Hewett and Trefethen [1] state that “One of the few mathematical treatments we have found is in section 7-5 of Vol. 2 of The Feynman Lectures on Physics, where so far as we can tell, the analysis is incorrect”. -

Advanced Faraday Cage Measurements of Charge, Short-Circuit Current and Open-Circuit Voltage by M

Advanced Faraday Cage Measurements of Charge, Short-Circuit Current and Open-Circuit Voltage by M. Shahrooz Amin Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Science in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 2004 0 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of A uthor:.......... ........... .............................................. Department of ElectricalEngineering and Computer Science August 31, 2004 Certified by: Markus Zahn Professor-6f Electrica gincd ig T-1~ Sup'~ryisor Accepted by:..... Artnur 3imch Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students MASSACHUSETTS INS1T E OF TECHNOLOGY OCT 2 8 2004 LIBRARIES BARKER Advanced Faraday Cage Measurements of Charge, Short-Circuit Current, and Open-Circuit Voltage by M. Shahrooz Amin Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science on August 31, 2004 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Abstract This thesis is devoted to Faraday cage measurements of air, liquid, and solid dielectrics. Experiments use pressurized air with fixed Faraday cage electrodes, and a moving sample of liquid and solid dielectrics between two Faraday cup electrodes. Extensive experiments were conducted to understand the source of the unpredictable net measured charge. In the air experiment, the Faraday cage consists of a hollow, cylindrical, gold- plated brass electrode mounted within a gold-plated brass hermetic chamber that connects with earth ground. Measurements of transient current at various temperatures and humidity during transient air pressure change are presented. The flow of electrode current is shown not to be due to capacitance and input offset voltage changes, since the calculated value is on the order of 10-16 Amperes which is much less than the measured currents of order 10-13 Amperes. -

Is Your Microwave a Faraday Cage?

Is your Microwave a Faraday Cage? Suggested Age / Curriculum Covered Duration Grade Level Grade 4 - 8 Energy, Technology, 40-45 minutes Electrical Systems Learning goals Students will explore energy and the electromagnetic spectrum in the world around them. The activity tests the connection between Frequency and Faraday Cages by testing Microwaves. Fun Facts ● Common cell phone frequency is 700 MHz ● Common WiFi frequency is 2.4 GHz ● Most Microwaves operate at 2.45 GHz ● Microwaves work as Faraday cages to keep microwaves that heat your food from escaping. But Faraday cages also block waves from outside the Microwave getting in too. https://www.britannica.com/technology/EHF Key Terms Faraday Cage - The cage is made of a metal screen which shields the contents inside the cage from electricity. The metal screen conducts electricity so when it comes in contact with an electric wave, it adds that electricity to the cage rather than allowing the wave to pass through. The metal screen set up in a Faraday cage only works if the holes in the screen are smaller than the wavelength of the incident wave (smaller wavelength = higher frequency) Electricity - the movement of small charged particles. The participles are either Electrons (these particles are negatively charged) or Protons (positively charged). Electromagnetic Field - a force field that surrounds a charged particle, such as an electron. They are produced by moving electric charges and it's a combination of both an electric field and a magnetic field. The electric field is produced by stationary charges and the magnetic field by moving charges (current). -

Lifting the Lid on the Potentiostat: a Beginner’S Guide to Understanding Electrochemical Circuitry Cite This: Phys

PCCP View Article Online TUTORIAL REVIEW View Journal | View Issue Lifting the lid on the potentiostat: a beginner’s guide to understanding electrochemical circuitry Cite this: Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2021, 23, 8100 and practical operation† Alex W. Colburn, a Katherine J. Levey,ab Danny O’Hare c and Julie V. Macpherson *a Students who undertake practical electrochemistry experiments for the first time will come face to face with the potentiostat. To many this is simply a box containing electronics which enables a potential to be applied between a working and reference electrode, and a current to flow between the working and counter electrode, both of which are outputted to the experimentalist. Given the broad generality of electrochemistry across many disciplines it is these days very common for students entering the field to have a minimal background in electronics. This article serves as an introductory tutorial to those with no formalized training in this area. The reader is introduced to the operational amplifier, which is at the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. heart of the different potentiostatic electronic circuits and its role in enabling a potential to be applied and a current to be measured is explained. Voltage follower op-amp circuits are also highlighted, given their importance in measuring voltages accurately. We also discuss digital to analogue and analogue to digital conversion, the processes by which the electrochemical cell receives input signals and outputs Received 11th February 2021, data and data filtering. By reading the article, it is intended the reader will also gain a greater confidence Accepted 9th March 2021 in problem solving issues that arise with electrochemical cells, for example electrical noise, DOI: 10.1039/d1cp00661d uncompensated resistance, reaching compliance voltage, signal digitisation and data interpretation. -

Gerard Turner Memorial Lecture Instruments from Scratch? Humphry Davy, Michael Faraday and the Construction of Knowledge Frank A.J.L

Gerard Turner Memorial Lecture Instruments from Scratch? Humphry Davy, Michael Faraday and the Construction of Knowledge Frank A.J.L. James A few wires and some old bits of wood and iron seem to serve him [Faraday] for the greatest discoveries.1 So wrote the Prussian physiologist and physi- cist Herman Helmholtz (1821–1894) to his wife in August 1853 after being shown by Michael Faraday (1791–1867) some of the apparatus he had used during the previous few decades in the Royal Institution’s base- ment laboratory. Although Helmholtz did not specify what Faraday had shown him, the ‘bits of wood and iron’ probably included the ring with which he discovered electro-mag- netic induction in 1831 and the magneto-elec- tric generator that he used a few weeks later, as well as the equipment he used in 1845 to discover the magneto-optical (‘Faraday’) ef- fect and diamagnetism with his giant electro- magnet. At first sight these pieces conform to Helmholtz’s description. But had he seen the electro-chemical apparatus used by Fara- Fig. 1 Thomas Beddoes’s pneumatic apparatus designed by James Watt. From Thomas day in the early 1830s when formulating his Beddoes and James Watt, Considerations on the Medicinal Use of Factitious Airs, and on the electro-chemical laws, during which he intro- manner of obtaining them in large quantities, parts 1 and 2, London: Johnson and Murray, duced terms such as electrode, cathode and printed Bristol, by Bulgin and Rosser, [1794]. No example of this apparatus has been located, ion into scientific language, he would have perhaps miscatalogued in some collection. -

The Heuristic Model of Energy Propagation in Free Space

Open Physics 2020; 18: 212–229 Research Article Chithra Kirthi Gamini Piyadasa*, Udaya Annakkage, Aniruddha Gole, Athula Rajapakse, and Upeka Premaratne The heuristic model of energy propagation in free space, based on the detection of a current induced in a conductor inside a continuously covered conducting enclosure by an external radio frequency source https://doi.org/10.1515/phys-2020-0102 placed inside a Faraday shield along with other existing received October 23, 2019; accepted March 18, 2020 observations in physics such as those in famous Young’s - Abstract: The objective of this study is to propose a double slit experiment on interference of light, which heuristic model of energy propagation due to an anomaly; provided the basis for the wave theory. electromagnetic (EM) field penetration into a continuously Keywords: electromagnetic fields, Faraday shield (cage), covered conducting enclosure (Faraday shield) from an electric and magnetic field electromagnetic induction, external radio frequency source, violating the accepted induced current, intrinsic spin energy, intrinsic spin model in the EM field theory. In this study, at an arbitrarily energy field, δ-spin, λ-spin selected frequency, range of 26.965–1,800 MHz, of an external frequency source, an EM field inside the con- ducting enclosure was observed, contrary to expectations, which was followed by a systematic examination. Although 1 Introduction no induced voltage could be expected inside the enclosure As any new revelation has a bearing on the accepted existing according to the classical theory, the experiment revealed knowledge, some analysis of the electromagnetic (EM) field a clear induced voltage inside, an attenuated induced becomes expedient. -

ENG517 Electromagnetism and Fields

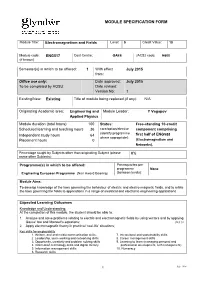

MODULE SPECIFICATION FORM Module Title: Electromagnetism and Fields Level: 5 Credit Value: 10 Module code: ENG517 Cost Centre: GAEE JACS2 code: H600 (if known) Semester(s) in which to be offered: 1 With effect July 2015 from: Office use only: Date approved: July 2015 To be completed by AQSU: Date revised: Version No: 1 Existing/New: Existing Title of module being replaced (if any): N/A Originating Academic area: Engineering and Module Leader: Y Vagapov Applied Physics Module duration (total hours) 100 Status: Free-standing 10-credit Scheduled learning and teaching hours 36 core/option/elective component comprising (identify programme Independent study hours 64 first half of ENG588 where appropriate): Placement hours 0 (Electromagnetism and Networks). Percentage taught by Subjects other than originating Subject (please 0% name other Subjects): Programme(s) in which to be offered: Pre-requisites per programme None Enginering European Programme (Non Award Bearing) (between levels): Module Aims: To develop knowledge of the laws governing the behaviour of electric and electro-magnetic fields, and to relate the laws governing the fields to applications in a range of electrical and electronic engineering applications. Expected Learning Outcomes Knowledge and Understanding: At the completion of this module, the student should be able to: 1. Analyse and solve problems relating to electric and electromagnetic fields by using vectors and by applying Gauss' law and Maxwell's equations; (KS 3) 2. Apply electromagnetic theory in practical ‘real-life’ situations; Key skills for employability 1. Written, oral and media communication skills, 7. Intercultural and sustainability skills 2. Leadership, team working and networking skills 8. -

Faraday Cage 43 Db Noise Reduction

Electrophysiology Electrochemistry Faraday Cage 43 dB noise reduction Standard stand-alone Faraday Cage HEKA provides the finest instruments today to achieve the needed progress of tomorrow… 1 Faraday Cage 43 dB noise reduction Introduction In many applications, the signal-to-noise ratio can be improved only with the use of a Faraday cage. A Faraday cage shields by suppressing the magnetic and electric parts of the electromagnetic waves due to high surface conductance and high permeability. Both stand-alone cages for use with an anti-vibration table and a bench-top model are available. Besides the model listed below customer specific Faraday Cages can be produced on request. Standard stand-alone Faraday Cage with Front Door Option. Features Stand-alone Standard Faraday Cage Material The Faraday cages are made of steel without the use of stainless steel or aluminum. The walls are of rug- ged construction and consist of coated punched sheet metal. Grounding Bar All instruments can be grounded at one central grounding bar. A set of cables for grounding the devices inside the cage are provided with the faraday cage. The upper and lower part of the cage are electrically connected. Shielding The noise is reduced by 43 dB (bandwidth 3 kHz). Design The stand-alone versions are of open-front design, but a front door option can be provided on request. Color All Faraday Cages are painted in HEKA blue (HSK 40) 2 Models Standard Faraday Cage The stand-alone Faraday cage consists of two parts: the stand (lower part) and the cage (upper part), which are mounted together in the laboratory.