No. 1 (13) 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chromatographic Determination of Caffeine Contents in Soft and Energy Drinks Available on the Romanian Market

Studii şi Cercetări Ştiinţifice 2010, 11 (3), pp. 351 – 358 Chimie şi Inginerie Chimică, Biotehnologii, Industrie Alimentară Scientific Study & Research Chemistry & Chemical Engineering, Biotechnology, Food Industry ISSN 1582-540X ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER CHROMATOGRAPHIC DETERMINATION OF CAFFEINE CONTENTS IN SOFT AND ENERGY DRINKS AVAILABLE ON THE ROMANIAN MARKET Violeta Nour1*, Ion Trandafir2, Mira Elena Ionică2 1University of Craiova, Faculty of Horticulture, 13 A.I. Cuza Street, Craiova, Romania 2University of Craiova, Faculty of Chemistry, 1071 Calea Bucuresti Blvd., Craiova, Romania *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: June 1, 2010 Accepted: September 30, 2010 Abstract: Caffeine is a stimulant that is commonly found in many foods and drinks that we consume. Concerns exist about the potential adverse health effects of high consumption of dietary caffeine, especially in children and pregnant women. Recommended caffeine intakes corresponding to no adverse health effects have been suggested recently for healthy adults (400 – 450 mg/day), for women contemplating pregnancy (300 mg/day), and for young children age 4 – 6 years (45 mg/day). Different brands of soft and energy carbonated beverages available on the Romanian market were analysed for caffeine by HPLC with a diode array UV-VIS detector at 217 nm. The column was a reverse phase C18 and the mobile phase consisted of potassium dihydrogen orthophosphate buffer (0.02 mol/L, pH 4.3) and acetonitrile (88:12, v/v). The caffeine contents in energy drink samples ranged from 16.82 mg/100 mL to 39.48 mg/100 mL while the carbonated soft drink group showed caffeine content in the range of 9.79 – 14.38 mg/100 mL. -

Cultural Remix: Polish Hip-Hop and the Sampling of Heritage by Alena

Cultural Remix: Polish Hip-Hop and the Sampling of Heritage by Alena Gray Aniskiewicz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Slavic Languages and Literatures) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Benjamin Paloff, Chair Associate Professor Herbert J. Eagle Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett Visiting Assistant Professor Jodi C. Greig, University of Wisconsin-Madison Alena Gray Aniskiewicz [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-1922-291X © Alena Gray Aniskiewicz 2019 To my parents, for everything. (Except hip-hop. For that, thank you, DH.) ii Acknowledgements To Herb Eagle, whose comments and support over the years have been invaluable. To Jodi Greig, whose reputation preceded her, but didn’t do her justice as a friend or scholar. To Charles Hiroshi Garrett, who was my introduction to musicology fourteen years ago and has been a generous reader and advisor ever since. And to Benjamin Paloff, who gave me the space to figure out what I wanted and then was there to help me figure out how to get it. I couldn’t have asked for a better committee. To my peers, who became friends along the way. To my friends, who indulged all the Poland talk. To Culture.pl, who gave me a community in Warsaw and kept Poland fun. To the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, the Copernicus Program in Polish Studies, the Rackham Graduate School, and the Sweetland Writing Center, whose generous funding made this dissertation possible. I’m thankful to have had you all in my corner. -

Energy Drinks Survey 2015

Energy Drinks Survey 2015 - All Data Data table sorted by category, alphabetically, highest sugars (g) per serving Product information was collected online, instore or direct from manufacturers Colour coding based on new front of pack colour-coded nutrition labelling criteria Sugars - Red >13.5g/portion or >11.25g/100ml, Amber >2.5≤11.25/100ml, Green *Serving/portion size ranged from 60 – 500ml. For products sold in 1 litre bottles, 250ml serving size was used in calculating the sugar content per serving. Brand Name Product Name Serving Size Energy (kcal) Sugar (g) per Teaspoons of sugar (ml) per serving* serving* per serving* Rockstar Rockstar Punched Energy + Guava Tropical Guava Flavour 500ml 500 335 78.0 20 Rockstar Rockstar Juiced Energy + Juice Mango Orange Passion Fruit Flavour 500ml 500 330 76.0 19 Rockstar Rockstar Punched Energy + Punch Fruit Punch Flavour 500ml 500 320 76.0 19 Lucozade Lucozade Energy Pink Lemonade 500ml 500 285 70.0 18 Lucozade Lucozade Energy Caribbean Crush 500ml 500 285 70.0 18 Rockstar Rockstar Super Sours Energy Drink Bubbleburst 500ml 500 295 69.0 17 Rockstar Rockstar Xdurance Performance Energy Blueberry, Pomegranate and Acai Flavour 500ml 500 285 69.0 17 Rockstar Rockstar Super Sours Energy Drink Green Apple 500ml 500 295 69.0 17 Rockstar Rockstar Energy Cola 500ml 500 280 68.0 17 Rockstar Rockstar Energy Drink 500ml 500 295 67.5 17 Rockstar Rockstar Xdurance Performance Energy Orange Flavour 500ml 500 275 67.5 17 Rockstar Rockstar Xdurance Performance Energy Tropical Orange Flavour 500ml 500 280 67.5 -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 1. List of abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Non-jihadist foreign fighters: a theoretical basis ...................................................................................... 8 4. Historical timeline ................................................................................................................................................. 13 5. Case study ................................................................................................................................................................. 21 5.1 Data collection: building a foreign fighter database .............................................................................. 21 5.2 Data analysis and results ................................................................................................................................. 24 5.3 Profiles and groups of foreign fighters ...................................................................................................... 28 6. Non-jihadist foreign fighters on social media .......................................................................................... 37 6.1 Instagram .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Lista Indeksów Promocyjnych

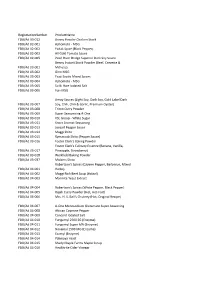

Załącznik nr 1 do Regulaminu promocji „Tarcza obrotowa 2020” L.p. Dostawca nr indeksu Nazwa produktu 1. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 4603 CUKIER WANILIOWY WINIARY 16G 2. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 884 BUDYŃ WINIARY ŚMIETANKOWY 60G 3. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 190776 GALARETKA WINIARY TRUSKAWKOWA 71G 4. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 1019 BUDYŃ WINIARY WANILIOWY 60G 5. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 1078 KISIEL WINIARY TRUSKAWKOWY 77G 6. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 213889 GALARETKA WINIARY MALINOWA 71G 7. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 190548 GALARETKA WINIARY CYTRYNOWA 71G 8. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 190546 GALARETKA WINIARY WIŚNIOWA 71G 9. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 1048 BUDYŃ WINIARY CZEKOLADOWY 63G 10. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 1112 KISIEL WINIARY WIŚNIOWY 77G 11. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 335223 GALARETKA WINIARY PRZEŹROCZ.WINOGR.71G 12. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 376396 GALARETKA WINIARY LEMONIADA 47G 13. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 376397 GALARETKA WINIARY ARBUZADA 47G 14. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 376395 GALARETKA WINIARY COLA 47G 15. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 4231 KWASEK CYTRYNOWY WINIARY 50G 16. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 1199 KISIEL WINIARY CYTRYNOWY 77G 17. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 203039 GALARETKA WINIARY POMARAŃCZ.75G 18. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 231369 CUKIER WANILINOWY WINIARY 32G 19. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 190547 GALARETKA WINIARY AGRESTOWA 75G 20. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 203040 GALARETKA WINIARY BRZOSKWINIOWA 71G 21. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 203023 KISIEL WINIARY POMARAŃCZ.77G 22. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 287136 GALARETKA WINIARY JAGODOWA 47G 23. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 203038 GALARETKA WINIARY POZIOMKOWA 75G 24. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. 203024 KISIEL WINIARY MALINOWY 77G 25. NESTLE POLSKA S.A. -

Development and Validation of Chromatographic Methods for The

Sudan University of Science and Technology College of Graduate Study Development and Validation of Chromatographic Methods for the Analysis of 4-Methylimidazole and Taurine in Carbonated Beverages انتطوير وانتحقق من طرق انكروماتوغرافيا نتحهيم 4-ميثيم إيمادزول و تورين في انمشروبات انغازية A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in chemistry By Maida Musa Ali Omer B. Sc. Laboratory Science (Chemistry) SUST (2006) Post Graduate Diploma (Chemistry) SUST(2016) Supervisor Prof. Abdalla Ahmed Elbashir Ahmed Co supervisor: Dr. Mohammed Elmukhtar Abdelaziz December, 2018 اﻵية لاي حعاَٚ ﴿ :ٌٝ َِا أَ ْس َس ٍَْٕا ِِ ْٓ َل ْب ٍِ َه إِ اَّل ِس َخا اَّل ُٛٔ ِحٟ إِ ٌَ ١ْ ِٙ ُْ َفا ْسأٌَُٛا أَ ْ٘ ًَ اٌ ِزّ ْو ِش إِ ْْ ُو ْٕخُ ُْ ََّل حَ ْع ٍَ ُّٛ َْ ﴾ صذق هللا اٌعظ١ُ سٛسة إٌحً ا٠٢ت }43{ I Dedication To my beloved parents, To my sisters and brothers, To my friends i Acknowledgments My full praise and thanks to our God for his guidance and gave me the strength to complete my study. I would like to express my deepest grateful to my supervisor, Professor Abdalla Ahmed Elbashir for his encouragement, support, deep discussion and scientific guidance throughout the period of my study. I am deeply appreciate to him for arranging of the necessary funding. My thankfulness to my co. supervisor Dr. Mohammed Elmukhtar Abd elaziz for his great help. I gratefully acknowledge the financial assistance provided by Arab-German Young Academy of Sciences and Humanities (AGYA) and Ministry of Higher Education & Scientific Research, Commission of scientific research and Innovation for research funding. -

MSG FDB/Ad 02-002 Yadak Spice

RegistrationNumber ProductName FDB/Ad 00-012 Benny Powder Chicken Stock FDB/Ad 02-001 Ajinomoto - MSG FDB/Ad 02-002 Yadak Spice (Black Pepper) FDB/Ad 02-003 All Gold Tomato Sauce FDB/Ad 02-005 Pearl River Bridge Superior Dark Soy Sauce Benny Instant Stock Powder (Beef, Crevette & FDB/Ad 03-001 Mchuzu) FDB/Ad 03-002 Gino MSG FDB/Ad 03-003 Yaaji Exotic Mixed Spices FDB/Ad 03-004 Ajinomoto - MSG FDB/Ad 03-005 So Bi Hwe Iodated Salt FDB/Ad 03-006 Fun-MSG Amoy Sauces (Light Soy, Dark Soy, Gold Label Dark FDB/Ad 03-007 Soy, Chili, Chili & Garlic, Premium Oyster) FDB/Ad 03-008 Triton Curry Powder FDB/Ad 03-009 Super Seasonoing A-One FDB/Ad 03-010 KSL Group - White Sugar FDB/Ad 03-011 Knorr Aromat Seasoning FDB/Ad 03-013 Joecarl Pepper Sauce FDB/Ad 03-014 Maggi Shito FDB/Ad 03-015 Rymaccob Shito (Pepper Sauce) FDB/Ad 03-016 Foster Clark's Baking Powder Foster Clark's Culinary Essence (Banana, Vanilla, FDB/Ad 03-017 Pineapple, Strawberry) FDB/Ad 03-018 Weikfield Baking Powder FDB/Ad 03-037 Midams Shito Robertson's Spices (Cayene Pepper, Barbecue, Mixed FDB/Ad 04-001 Herbs) FDB/Ad 04-002 Maggi Rich Beef Soup (Halaal) FDB/Ad 04-003 Marmite Yeast Extract FDB/Ad 04-004 Robertson's Spices (White Pepper, Black Pepper) FDB/Ad 04-005 Rajah Curry Powder (Hot, Hot-Fort) FDB/Ad 04-006 Mrs. H. S. Ball's Chutney (Hot, Original Recipe) FDB/Ad 04-007 A-One Monosodium Glutamate Super Seasoning FDB/Ad 04-008 African Cayenne Pepper FDB/Ad 04-009 Concord Iodated Salt FDB/Ad 04-010 Fungamyl 2500 SG (Enzyme) FDB/Ad 04-011 Fungamyl Super MA (Enzyme) FDB/Ad 04-012 Novamyl -

Annex 9: Selective

List of Excise Goods Total Price Unique current Common Category Brand Name Item Name Tax % Tax Amount (Including Code Price Tax) 1 Carbonated Drink Pepsi Pepsi Wild Cherry 355ml 50% BHD 0.175 BHD 0.525 BHD 0.350 2 Carbonated Drink BUDWEISER BUDWEISER N/A BEER CAN 355ML 50% BHD 0.138 BHD 0.413 BHD 0.275 3 Carbonated Drink BUDWEISER BUDWEISER N/A BEER APPLE BTTL 355ML 50% BHD 0.138 BHD 0.413 BHD 0.275 4 Carbonated Drink BUDWEISER BUDWEISER N/A BEER APPLE CAN 355ML 50% BHD 0.138 BHD 0.413 BHD 0.275 5 Carbonated Drink Coca ‐ Cola Coca Cola CHERRY COKE 355ML 50% BHD 0.175 BHD 0.525 BHD 0.350 6 Carbonated Drink SPRITE SPRITE ZERO 355M 50% BHD 0.225 BHD 0.675 BHD 0.450 7 Carbonated Drink DR.PEPPER Dr Pepper CAF Free 355ml 50% BHD 0.198 BHD 0.593 BHD 0.395 8 Carbonated Drink DR.PEPPER DR PEPPER VANILLA 355M 50% BHD 0.145 BHD 0.435 BHD 0.290 9 Carbonated Drink CRUSH CRUSH DIET ORANGE 355ML 50% BHD 0.113 BHD 0.338 BHD 0.225 10 Carbonated Drink CRUSH Crush Grape 355ml 50% BHD 0.175 BHD 0.525 BHD 0.350 11 Carbonated Drink DR.PEPPER Dr Pepper Cherry 355ml 50% BHD 0.163 BHD 0.488 BHD 0.325 12 Carbonated Drink HOLSTEN Holsten‐ Non alcholic Malt Beverage‐Can 500ml 50% BHD 0.200 BHD 0.600 BHD 0.400 13 Carbonated Drink FANTA FANTA ORANGE PET 500ML 50% BHD 0.100 BHD 0.300 BHD 0.200 14 Carbonated Drink FANTA FANTA STRAWBERRY 150ML 50% BHD 0.075 BHD 0.225 BHD 0.150 15 Carbonated Drink BRITVIC BRITVIC GINGER ALE 150ML 50% BHD 0.150 BHD 0.450 BHD 0.300 16 Carbonated Drink FANTA FANTA CITRUS 150ML 50% BHD 0.075 BHD 0.225 BHD 0.150 17 Carbonated Drink Coca ‐ -

207196-201105312126540.Pdf

COMPANY PROFILE Eko-Vit – is a leading Polish soft drinks producer with brands such as Ozone Energy Drink, Replay Energy Drink, Euphoria Energy Drink. PowerSport Isotonic Drink, Frutino and others. Present on the international market for more than 15 years, we are developing products from the recipe to the ready drink, using our own database of flavors or using our clients' ideas. We are specializing in energy drinks. Our products are present in USA, Ireland, Israel, Russia, Greece, Lebanon, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Kenya, Uganda, Finland, Cyprus, Italy, Qatar, Romania, Hungary, Chile, Czech Republic, Sweden, Finland, France, Germany, Portugal, Denmark, China, Australia, South Africa and other countries. Since a lot of clients are requesting private label designs, Eko-Vit decided to create a graphic studio, that is helping our clients to develop the best possible designs, according to the latest design and production standards. Eko-Vit has a long lasting cooperation with transport companies (Maersk, ZIM, M&M, C.Hartwig) which enables us to offer unbeatable CIF prices for different products our customers may desire. PRODUCTS Our product portfolio consists of: • Classic energy drinks • Sugar free energy drinks • Flavoured energy drinks: cranberry, lemon-lime, wild berry, cola • Love drinks with damiana, guarana, ginseng and gingko-biloba • Energy Drink with vodka 4,9%, 10.5% and 14.9% • Alco-pops (5% of alcohol) in two flavours: lemon and cranberry • Fruit drinks (up to 21% of juice) in two flavours: apple-mint and apple-cherry • Ice-teas • Lemonades Our laboratory can provide custom made compositions made for clients’ needs. OUR BRANDS CLIENTS We are proud to cooperate with big international distributors and supermarket chains. -

Energy Drinks Survey 2015

Energy Drinks Survey 2015 - All Data Data table sorted by category, alphabetically, highest sugars (g) per 100ml Product information was collected online, instore or direct from manufacturers Colour coding based on new front of pack colour-coded nutrition labelling criteria Sugars - Red >13.5g/portion or >11.25g/100ml, Amber >2.5≤11.25/100ml, Green ≤2.25g/100ml Brand Name Product Name Sugars (g) per 100ml Sainsbury's Sainsbury's Orange Energy Drink 1L 15.9 Rockstar Rockstar Punched Energy + Guava Tropical Guava Flavour 500ml 15.6 Rockstar Rockstar Juiced Energy + Juice Mango Orange Passion Fruit Flavour 500ml 15.2 Rockstar Rockstar Punched Energy + Punch Fruit Punch Flavour 500ml 15.2 Red Devil Red Devil Energy Drink 250ml 15.0 Lucozade Lucozade Energy Pink Lemonade 500ml 14.0 Lucozade Lucozade Energy Caribbean Crush 500ml 14.0 Lucozade Lucozade Energy Pink Lemonade 380ml 14.0 Lucozade Lucozade Energy Caribbean Crush 380ml 14.0 Innocent Innocent Super Smoothie Energise 360ml 14.0 Lucozade Lucozade Energy Pink Lemonade 1L 14.0 Rockstar Rockstar Super Sours Energy Drink Bubbleburst 500ml 13.8 Rockstar Rockstar Xdurance Performance Energy Blueberry, Pomegranate and Acai Flavour 500ml 13.8 Rockstar Rockstar Super Sours Energy Drink Green Apple 500ml 13.8 Rockstar Rockstar Energy Cola 500ml 13.6 Rockstar Rockstar Energy Drink 500ml 13.5 Rockstar Rockstar Xdurance Performance Energy Orange Flavour 500ml 13.5 Rockstar Rockstar Xdurance Performance Energy Tropical Orange Flavour 500ml 13.5 Lucozade Lucozade Energy Lemon 380ml 13.5 Lucozade Lucozade -

Jfcn-065-Maida-Musa-Ali-Omer.Pdf

ournal of JFood Chemistry & Nanotechnology https://doi.org/10.17756/jfcn.2019-065 Research Article Open Access Liquid Chromatographic and Spectrophotometric Determination of Taurine in Energy Drinks Based on O-Phthalaldehyde-Sulfite Derivatization Maida Musa Ali Omer1, Mei Musa Ali Omar2, Mohammed Almokhtar Abdelaziz1, Andreas Thiel3 and Abdalla Ahmed Elbashir4* 1Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Sudan University of Science and Technology, Sudan 2Central Laboratory, Ministry of Higher Education & Scientific Research, Khartoum, Sudan 3Faculty of Organic Agricultural Sciences, University of Kassel, Steinstr, Witzenhausen, Germany 4Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan *Correspondence to: Abdalla Ahmed Elbashir Abstract Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science Rapid and efficient high-performance liquid chromatographic and UV-Vis University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan E-mail: [email protected] spectrophotometric methods have been optimized and validated for taurine determination in energy drinks. Taurine was derivatized with o-phthalaldehyde Received: November 02, 2018 and sodium sulfite in alkaline media prior to analysis. The optimum derivatization Accepted: January 02, 2019 parameters were found to be 0.1 M borate buffer at pH 9.5, reaction time 5.0 Published: January 05, 2019 min, o-phthalaldehyde concentration of 60 mg L-1, sodium sulfite concentration Citation: Omer MMA, Omar MMA, Abdelaziz of 202 mg L-1 and water as diluting solvent. The analytical parameters such as MA, Thiel A, Elbashir AA. 2019. Liquid linearity, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), precision and Chromatographic and Spectrophotometric accuracy were investigated. The methods were linear in range 0.5-20 mg L-1 and Determination of Taurine in Energy Drinks Based -1 2 on O-Phthalaldehyde-Sulfite Derivatization. -

Not Collected and Caffeine Label May

NA - product did not exist in 2015, so caffeine data collection was not applicable NC - not collected and caffeine label may have not been available NL - no caffeine warning label Brand Name Product Name Pack Size Energy Energy Sugars (g) Sugars (g) Caffeine Caffeine (ml) (kcal) per (kcal) per per 100ml per 100ml (mg) per (mg) per 100ml 100ml 2015 2017 100ml 100ml 2015 2017 2015 2017 PepsiCo Tropicana Energy Mango and Guava with Passionfruit 150ml 150 53 10.9 NC NA PepsiCo Tropicana Energy Pineapple, Mango and Banana 150ml 150 49 9.8 NC NA Tesco Tesco Blue Spark 6 x 250ml 250 44 24 9.8 4.9 32.0 30.0 Lidl Lidl Freeway Up Tropical Juiced Energy Drink 250ml 250 46 36 10.5 8.8 NC 32.0 Lidl Lidl Freeway Up Berry Juiced Energy Drink 250ml 250 36 8.8 NA 32.0 Asda Asda Chosen by You Original Blue Charge 250ml 250 48 37 10.7 7.7 NC 30.0 Asda Asda Chosen by You Chai Spice Flavour Blue Charge 250ml 250 43 9.6 30.0 NA Lucozade Lucozade Energy Pink Lemonade 250ml 250 40 6.8 NA NL Cott Emerge Energy Drink Original 250ml 250 42 42 9.8 9.3 30.0 30.0 Scheckter's Scheckter's Organic Energy 250ml 250 47 43 10.8 10 NC 32.0 Lidl Lidl Freeway Up Lime Energy Drink 250ml 250 44 10.9 NA 32.0 Lidl Lidl Freeway Up Classic Stimulation Drink 250ml 250 44 9.9 NA 30.0 Red Bull Red Bull Energy Drink The Orange edition 250ml 250 45 11 NA 32.0 V V Guarana Energy Drink 250ml 250 45 45 11.2 11 NC 31.0 Morrisons Morrisons Source Orange and Passion Fruit Energy Drink 250ml 250 46 46 10.6 10.6 30.0 30.0 Red Bull Red Bull Energy Drink 250ml 250 46 46 11.0 11 NC 32.0 Dico MTV