Don't Back Away: an Interview with Rae Armantrout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry Magazine

Poetry Magazine 2008- January Articles Made to Measure, The Red Sea Devotion: The Garment District Nocturnal, Divine Rights Devotion: The Burnt-Over District Stephen Edgar Bruce Smith callas lover, cruel, cruel summer The History of Mothers of Sons D.A. Powell Lisa Furmanski Man of War, Argonaut's Vow Pink Ocean Carol Frost Stuart Dybek The Solipsist The Taste of Silence Troy Jollimore Adam Kirsch Citation Responsibilities Joshua Mehigan Joanie V. Mackowski Repetition,The Late Worm, Clamor and Quiet Cut Out For It Ange Mlinko Kay Ryan Closing the Circle Getting Where We're Going Jhumpa Lahiri John Brehm A Night in Brooklyn The Dead Remember Brooklyn The Rain-Streaked Avenues of Central Queens D. Nurkse Moose Dreams, Dogwood William Johnson Biographer Samuel Menashe La Porte Rachel Webster There's Nothing More Wendy Videlock Poetry Magazine 2008- Feb. Articles Midsummer, Dawn Leaving Prague: A Notebook Louise Glück Alexei Tsvetkov bon bon il est un pays, Mort de A.D. Four Takes à elle l’acte calme, Ascension D. H. Tracy La Mouche, Arènes de Lutèce Samuel Beckett Letter to the Editor James Matthew Wilson Fowling Piece Heidy Steidlmayer Letter to the Editor Sean Lysaght An Old Woman’s Painting Letter to the Editor Jim Carmin Lynn Emanuel Letter to the Editor Michael Hudson Full Fathom Jorie Graham Letter to the Editor Robert Longoni J. Learns the Difference Between Letter to the Editor Adam Zagajewski Poverty and Having No Money Jeffrey Schultz Stemming from Stevens Lisa Williams Ladybirds Larissa Szporluk Rose Thorns Molly McQuade Kertész: Latrine,Ross: Children of the Ghetto,Ross: Yellow Star Doisneau: Underground Press Sudek: Tree Petersen: Kleichen and a Man Kolár: Housing Estate George Szirtes Sincerity and Its Discontents in American Poetry Now Peter Campion Poetry Magazine 2008- March Articles Nights on Planet Earth Campbell McGrath Letter to the Editor William Watt Containment, The Catch Letter to the Editor Michael A.E. -

“Dark Matters,” by Mark Scroggins, from Parnassus

Dark Matters Rae Armantrout, Next Life. Wesleyan University Press 2007. 8 8pp. $13.95 (paper) Rae Armantrout, Versed. Wesleyan University Press 2009. 121pp. $22.95 Rae Armantrout, Collected Prose. Singing Horse Press 2007. 171pp. $17.00 (paper) Peter Gizzi, Some Values ofLandscape and Weather. Wesleyan University Press 2003. 112 pp. $14.95 (paper) Peter Gizzi, The Outernationale.Wesleyan University Press 2008. 111 pp. $13.95 (paper) O n the back cover of Some Values of Landscape and Weather, we're told that Peter Gizzi is "on the quixotic mission of recovering the lyric." While I had no idea we'd lost it, I sup- pose the blurbist has a point. Gizzi, who during the late 1980s and early 1990s co-edited the excellent and eclectic journal 0-bi14, writes within an avant-garde tradition that sometimes views melopceia with suspicion, or else discounts it entirely. What place song in the ranks of savage, analytic parataxis? I'm happy to report that whether or not the lyric actually needed "recovering," Some Values presents a range of wonderfully musical moments, as in the title poem to the book's "History of Lyric" section, a pre-Raphaelite idyll in a world of electronic static: I lost you to the inky noise just offscreen that calls us and partly we got stuck there waving, walking into the Percy grass. Dark Matters - 367 A sinking pictorial velvet spray imagining vermilion dusk. You lost me to your petticoat shimmering armor saying it is better here on my own amazon. Why can't we or is it won't you leave your solo ingle beside the page. -

Ron Silliman

© 2007 UC Regents Buy this book UC-Silliman 12/18/06 3:29 PM Page iv University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2007 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Silliman, Ronald, 1946–. [Age of huts] The age of huts (compleat) / Ron Silliman. p. cm. — (New California poetry ; 21) This title is one of a four-part poem cycle, which is entitled Ketjak. The parts are: The age of huts, Tjanting, The alphabet, & Universe. isbn: 978-0-520-25014-7 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn: 978-0-520-25016-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Silliman, Ronald, 1946– Ketjak. II. Title. ps3569.i445a7 2007 811'.54—dc22 2006025507 Manufactured in Canada 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 10987654321 This book is printed on New Leaf EcoBook 50, a 100% recycled fiber of which 50% is de-inked post-consumer waste, processed chlorine-free. EcoBook 50 is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of ansi/astm d5634–01 (Permanence of Paper). UC-Silliman 12/18/06 3:29 PM Page vii Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xi Ketjak / 1 Sunset Debris / 103 The Chinese Notebook / 147 -

Eigner Preface

Charles Bernstein: Foreword to Selected Poems of Larry Eigner (forthcoming, University of Alabama Press) The Imagined, Returning: Larry Eigner’s Endless Song Larry Eigner was born in Lynn, Massachusetts on August 7, 1927 and spent most of his life in nearby Swampscott, midway between Boston and Gloucester, just a few blocks from the ocean. Eigner lived in his parents’ house in Swampscott until 1978, when, shortly after his father’s death, he moved to Berkeley, where he lived until his death in 1996. These facts are bare, commensurate to Eigner’s poems, which bear witness to the preternatural spareness of his life, just as they bear the weight of a gravitational aesthetic force field unprecedented in American poetry. That’s an extravagant claim for a poet who averted extravagance. And it’s an incredible claim too, given Eigner’s obscurity: despite legions of fervent readers, Eigner’s magisterial four-volume, almost 2000-page Collected Poems, received virtually no public recognition when it was published by Stanford University Press in 2010. With this volume, Collected editors Robert Grenier and Curtis Faville have created a perfectly scaled introduction to the full scope of Eigner’s work.* To be an obscure poet is not to be obscure, to invert John Ashbery’s quip that a famous poet is not famous. Eigner’s work has made an indelible impact among the generation of poets brought together in the iconic 1960 New American Poetry anthology. Eigner’s poetry was recognized early on by Robert Creeley, Charles Olson, Denise Levertov, and Cid Corman and was subsequently published by hundreds of small press editors in pamphlets, books, and magazines. -

The Birth of Linguistically Innovative Poetry and the Practice of a Collective Poetics in Robert Sheppard’S Pages and Floating Capital Thurston, SD

“For which we haven’t yet a satisfactory name” : the birth of Linguistically Innovative Poetry and the practice of a collective poetics in Robert Sheppard’s Pages and Floating Capital Thurston, SD Title “For which we haven’t yet a satisfactory name” : the birth of Linguistically Innovative Poetry and the practice of a collective poetics in Robert Sheppard’s Pages and Floating Capital Authors Thurston, SD Type Book Section URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/48250/ Published Date 2019 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. 1 “For which we haven’t yet a satisfactory name”: The Birth of Linguistically Innovative Poetry and the Practice of a Collective Poetics in Robert Sheppard’s Pages and Floating Capital. In July 1987 Robert Sheppard published the first issue of a little magazine called Pages. The magazine was a humble affair, comprised of four folded A4 sheets to give eight printed pages per issue. Typescript material was pasted into camera ready copy format and photocopied.1 The editorial opens: Anybody concerned for a viable poetry in Britain must be depressed by the persistence of the Movement Orthodoxy from the 1950s into the late 80s; by its consolidation of power for a bleak future; by its neutralising assimilation of the surfaces of modernism; by its annexation of the increasingly fashionable term postmodernism; and by its ignorance – real or affected – of much of the work of the British Poetry Revival.2 This is very much a downbeat tone on which to begin a new enterprise. -

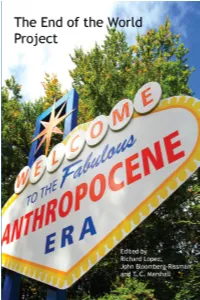

6X9 End of World Msalphabetical

THE END OF THE WORLD PROJECT Edited By RICHARD LOPEZ, JOHN BLOOMBERG-RISSMAN AND T.C. MARSHALL “Good friends we have had, oh good friends we’ve lost, along the way.” For Dale Pendell, Marthe Reed, and Sudan the white rhino TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ Trialogue xiii Overture: Anselm Hollo 25 Etel Adnan 27 Charles Alexander 29 Will Alexander 42 Will Alexander and Byron Baker 65 Rae Armantrout 73 John Armstrong 78 DJ Kirsten Angel Dust 82 Runa Bandyopadhyay 86 Alan Baker 94 Carlyle Baker 100 Nora Bateson 106 Tom Beckett 107 Melissa Benham 109 Steve Benson 115 Charles Bernstein 117 Anselm Berrigan 118 John Bloomberg-Rissman 119 Daniel Borzutzky 128 Daniel f Bradley 142 Helen Bridwell 151 Brandon Brown 157 David Buuck 161 Wendy Burk 180 Olivier Cadiot 198 Julie Carr / Lisa Olstein 201 Aileen Cassinetto and C. Sophia Ibardaloza 210 Tom Cohen 214 Claire Colebrook 236 Allison Cobb 248 Jon Cone 258 CA Conrad 264 Stephen Cope 267 Eduardo M. Corvera II (E.M.C. II) 269 Brenda Coultas 270 Anne Laure Coxam 271 Michael Cross 276 Thomas Rain Crowe 286 Brent Cunningham 297 Jane Dalrymple-Hollo 300 Philip Davenport 304 Michelle Detorie 312 John DeWitt 322 Diane Di Prima 326 Suzanne Doppelt 334 Paul Dresman 336 Aja Couchois Duncan 346 Camille Dungy 355 Marcella Durand 359 Martin Edmond 370 Sarah Tuss Efrik and Johannes Göransson 379 Tongo Eisen-Martin 397 Clayton Eshleman 404 Carrie Etter 407 Steven Farmer 409 Alec Finlay 421 Donna Fleischer 429 Evelyn Flores 432 Diane Gage 438 Jeannine Hall Gailey 442 Forrest Gander 448 Renée Gauthier 453 Crane Giamo 454 Giant Ibis 459 Alex Gildzen 460 Samantha Giles 461 C. -

Combating Conventional Realism and Commodity Fetishism In

International Journal of Linguistics andLiterature (IJLL) ISSN(P): 2319-3956; ISSN(E): 2319-3964 Vol. 7, Issue 5, Aug – Sep 2018; 33-48 © IASET COMBATING CONVENTIONAL REALISM AND COMMODITYFETISHISM IN REPRESENTATION OF EVERYDAY LIFE: ASTUDY OF RON SILLIMAN’S BART ON BART Abeer M. Refky M. Seddeek College of Language and Communication (CLC), Arab Academy for Science, Technology and Maritime Transport (AASTMT), Alexandria, Egypt ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is twofold; first it explains Everyday Life and Cultural Theory as based on the studies of Michael Sheringham, Ben Highmore, Guy Debord and the Situationists, and Henri Lefebvre. It shows that la vie quotidienneresists categorization and requires various forms of representation and discourse to reflect its continuum. It explains Everyday Life Theory concern with urban geography and the dérive technique as well as the dominance of Capitalism commodity fetish that commodified and stamped with value the social and political aspects, even language. Secondly, the paper discusses Ron Silliman’s BART on Bart’s (1982) probing of the quotidian through its structure that is based on accumulation, repetition, juxtaposition and extreme length, the new sentence and procedural constraint as means of describing the real. It shows the city as a whole in movement to explain the continuum of the everyday. The paper concludes that BART on Bart negates conventional realism and the capitalistic approach of commodification. KEYWORDS: Capitalism – Everyday Life and Cultural Theory – Marx’s Commodity Fetish – Realism – Situationism Article History Received: 08 Aug 2018 | Revised: 17 Aug 2018 | Accepted: 23 Aug 2018 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Significance of Study Language poetry, which emerged in the United States at the end of the 1960s and early 1970s, changes the poetic language from customary discourse. -

The Self in the Song: Identity and Authority in Contemporary

The Self in the Song: Identity and Authority in Contemporary American Poetry by David William Lucas A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Linda K. Gregerson, Chair Professor Yopie Prins Associate Professor Gillian Cahill White Professor John A. Whittier-Ferguson for my teachers ii Acknowledgments My debts are legion. I owe so much to so many that I can articulate only a partial index of my gratitude here: To Jonathan Farmer and At Length, in which an adapted and excerpted version of “The Nothing That I Am: Mark Strand” first appeared, as “On Mark Strand, The Monument.” To Steven Capuozzo, Amy Dawson, and the Literature Department staff of the Cleveland Public Library for their assistance with my research. To the Department of English Language and Literature and the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan for the financial and logistical support that allowed me to begin and finish this project. To the Stanley G. and Dorothy K. Harris Fund for a summer grant that allowed me to continue my work without interruption. To the Poetry & Poetics Workshop at the University of Michigan, and in particular to Julia Hansen, for their assistance in a workshop of the introduction to this study. To my teachers at the University of Michigan, and especially to Larry Goldstein and Marjorie Levinson, whose interest in this project, support of it, and suggestions for it have proven invaluable. To June Howard, A. Van Jordan, Benjamin Paloff, and Doug Trevor. -

Ange Mlinko Associate Professor Department of English University of Florida [email protected]

Ange Mlinko Associate Professor Department of English University of Florida [email protected] Education M.F.A. (Creative Writing, Poetry) Brown University, Providence RI, 1998 B.A. (Philosophy and Mathematics) St. John’s College, Annapolis MD, 1991 Teaching Experience Term Professor (2018-2023), University of Florida Associate Professor (2014-present), Creative Writing Program, Department of English, University of Flor- ida Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference (2018), Poetry Faculty Assistant Professor (2010-14), Creative Writing Program, Department of English, University of Houston Courses Developed and Taught Rhetorical Tropes (graduate seminar) The Long Poem (graduate seminar) Modernism and Ancient Greek Poetry (graduate seminar) Poetry Workshop (graduate workshop) Master Workshop (graduate workshop) Advanced Poetry Workshop (undergraduate workshop) Poetic Forms (undergraduate workshop) Poetry Projects (undergraduate workshop) Awards Guggenheim Fellowship, 2014-15 Frederick Bock Prize, Poetry magazine, 2012 Randall Jarrell Award for Criticism, Poetry Foundation, 2009 Editor’s Prize for Reviewing, Poetry magazine, 2008 National Poetry Series, 2004 Publishers Weekly Best Books of 1999 The Fund for Poetry, 1996 and 2006 Starred Wire was one of two finalists for the James Laughlin Award in 2005. Shoulder Season was a finalist for the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America in 2010, and a finalist for a PEN Center USA award. Marvelous Things Overheard was named a “best book of poetry” on year-end lists in the New Yorker -

In Early March 1981, Lyn Sent a Letter to Barrett, Bob, Charles Bernstein, Ron, and Steve, Proposing That Each Would Write A

In early March 1981, Lyn sent a letter to Barrett, Bob, Charles Bernstein, Ron, and Steve, proposing that each would write a page on a topic that she named, the whole to serve as an introduction to a selection of Language writings in French translation that would appear in Change magazine, as part of the March 1982 issue focused on “L’espace amérique,” edited (with an additional introduction) by Nanos Valaoritis. In 1989, our same six-person introduction was retranslated into Serbian and published in an issue of Delo, in Yugoslavia. Here is the six-person introduction. Ron Silliman, Barrett Watten, Steve Benson, Lyn Hejinian, Charles Bernstein, Bob Perelman Begun in the sixties, the writing of the American poets gathered here for Change matured into an organized, ongoing literary discourse in the following decade, a period of significant transition for the United States. From the perspective of capital, the war in Indochina was lost, a critical blow to national military prestige. More importantly, 1974 marked the end of capital’s longest “boom,” the expansionist years following the Second World War (on top of which the essential optimism of every variety of “New American” poetry had been constructed). Simultaneously, the largest generation in U.S. history, the “baby boom” of the 40’s and early 50’s, passed from college to the daily practices of material life. Tied to that generation and crippled from the beginning by its rejection of historical knowledge, the American New Left rapidly dissolved, although several of its veterans were to re-emerge as leaders of cross-class movements based on forms of personal oppression, as women or as gays of either sex. -

A Network Analysis of Postwar American Poetry in the Age of Digital Audio Archives Ankit Basnet and James Jaehoon Lee

Journal of April 20, 2021 Cultural Analytics A Network Analysis of Postwar American Poetry in the Age of Digital Audio Archives Ankit Basnet and James Jaehoon Lee Ankit Basnet, University of Cincinnati James Lee, University of Cincinnati Peer-Reviewer: Stephen Voyce Data Repository: 10.7910/DVN/NK7Z2H A B S T R A C T From the New American Poetry to New Formalism, publishing networks such as literary magazines and social scenes such as poetry reading series have served as a capacious model for understanding the varied poetic formations in the postwar period. As audio archives of poetry readings have been digitized in large volumes, Charles Bernstein has suggested that open access to digital archives allows readers of American poetry to create mixtapes in different configurations. Digital archives of poetry readings “offer an intriguing and powerful alternative” to organizing practices such as networks and scenes. Placing Bernstein’s definition of the digital audio archive into contact with more conventional understandings of poetic community gives us a composite vision of organizing principles in postwar American poetry. To accomplish this, we compared poetry reading venues as well as audio archives — alongside more familiar print networks constituted by poetry anthologies and magazines — as important and distinct sites of reception for American poetry. We used network analysis to visualize the relationships of individual poets to venues where they have read, archives where their readings are stored, and text anthologies where their poetry has been printed. Examining several types of poetic archives offers us a new perspective in how we perceive the relationships between poets and their “networks and scenes,” understood both in terms of print and audio culture, as well as trends and changes in the formation of these poetic communities and affiliations. -

Ron Silliman Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf696nb4f8 No online items Ron Silliman Papers Finding aid prepared by Special Collections & Archives Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, California, 92093-0175 858-534-2533 [email protected] Copyright 2005 Ron Silliman Papers MSS 0075 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Ron Silliman Papers Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0075 Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, California, 92093-0175 Languages: English Physical Description: 10.4 Linear feet(26 archives boxes) Date (inclusive): 1965-1988 Abstract: Papers of Ron Silliman, American writer and editor. Silliman has lived in the San Francisco Bay Area most of his life and is associated with the Language school of contemporary writers. He edited the anthology In The American Tree, published in 1986. The papers include extensive correspondence with many prominent contemporary writers, including Rae Armantrout, Charles Bernstein, Michael Davidson, Lyn Hejinian, Douglas Messerli, John Taggart, and Hanna Weiner. Also included are drafts of Silliman's published works, notebooks, and materials relating to In the American Tree. The collection is divided into five series: 1) ORIGINAL FINDING AID, 2) CORRESPONDENCE, 3) WRITINGS, 4) IN THE AMERICAN TREE and 5) ORIGINALS OF PRESERVATION PHOTOCOPIES. Creator: Silliman, Ronald, 1946- Scope and Content of Collection The Ron Silliman papers contain collected correspondence and writings related to Silliman's career as a writer. The materials cover a range from the mid-1960s to 1988, excluding his most recent publication WHAT (1988). The collection is divided into five series: 1) ORIGINAL FINDING AID, 2) CORRESPONDENCE, 3) WRITINGS, 4) IN THE AMERICAN TREE and 5) ORIGINALS OF PRESERVATION PHOTOCOPIES.