“Dark Matters,” by Mark Scroggins, from Parnassus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry Magazine

Poetry Magazine 2008- January Articles Made to Measure, The Red Sea Devotion: The Garment District Nocturnal, Divine Rights Devotion: The Burnt-Over District Stephen Edgar Bruce Smith callas lover, cruel, cruel summer The History of Mothers of Sons D.A. Powell Lisa Furmanski Man of War, Argonaut's Vow Pink Ocean Carol Frost Stuart Dybek The Solipsist The Taste of Silence Troy Jollimore Adam Kirsch Citation Responsibilities Joshua Mehigan Joanie V. Mackowski Repetition,The Late Worm, Clamor and Quiet Cut Out For It Ange Mlinko Kay Ryan Closing the Circle Getting Where We're Going Jhumpa Lahiri John Brehm A Night in Brooklyn The Dead Remember Brooklyn The Rain-Streaked Avenues of Central Queens D. Nurkse Moose Dreams, Dogwood William Johnson Biographer Samuel Menashe La Porte Rachel Webster There's Nothing More Wendy Videlock Poetry Magazine 2008- Feb. Articles Midsummer, Dawn Leaving Prague: A Notebook Louise Glück Alexei Tsvetkov bon bon il est un pays, Mort de A.D. Four Takes à elle l’acte calme, Ascension D. H. Tracy La Mouche, Arènes de Lutèce Samuel Beckett Letter to the Editor James Matthew Wilson Fowling Piece Heidy Steidlmayer Letter to the Editor Sean Lysaght An Old Woman’s Painting Letter to the Editor Jim Carmin Lynn Emanuel Letter to the Editor Michael Hudson Full Fathom Jorie Graham Letter to the Editor Robert Longoni J. Learns the Difference Between Letter to the Editor Adam Zagajewski Poverty and Having No Money Jeffrey Schultz Stemming from Stevens Lisa Williams Ladybirds Larissa Szporluk Rose Thorns Molly McQuade Kertész: Latrine,Ross: Children of the Ghetto,Ross: Yellow Star Doisneau: Underground Press Sudek: Tree Petersen: Kleichen and a Man Kolár: Housing Estate George Szirtes Sincerity and Its Discontents in American Poetry Now Peter Campion Poetry Magazine 2008- March Articles Nights on Planet Earth Campbell McGrath Letter to the Editor William Watt Containment, The Catch Letter to the Editor Michael A.E. -

6X9 End of World Msalphabetical

THE END OF THE WORLD PROJECT Edited By RICHARD LOPEZ, JOHN BLOOMBERG-RISSMAN AND T.C. MARSHALL “Good friends we have had, oh good friends we’ve lost, along the way.” For Dale Pendell, Marthe Reed, and Sudan the white rhino TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ Trialogue xiii Overture: Anselm Hollo 25 Etel Adnan 27 Charles Alexander 29 Will Alexander 42 Will Alexander and Byron Baker 65 Rae Armantrout 73 John Armstrong 78 DJ Kirsten Angel Dust 82 Runa Bandyopadhyay 86 Alan Baker 94 Carlyle Baker 100 Nora Bateson 106 Tom Beckett 107 Melissa Benham 109 Steve Benson 115 Charles Bernstein 117 Anselm Berrigan 118 John Bloomberg-Rissman 119 Daniel Borzutzky 128 Daniel f Bradley 142 Helen Bridwell 151 Brandon Brown 157 David Buuck 161 Wendy Burk 180 Olivier Cadiot 198 Julie Carr / Lisa Olstein 201 Aileen Cassinetto and C. Sophia Ibardaloza 210 Tom Cohen 214 Claire Colebrook 236 Allison Cobb 248 Jon Cone 258 CA Conrad 264 Stephen Cope 267 Eduardo M. Corvera II (E.M.C. II) 269 Brenda Coultas 270 Anne Laure Coxam 271 Michael Cross 276 Thomas Rain Crowe 286 Brent Cunningham 297 Jane Dalrymple-Hollo 300 Philip Davenport 304 Michelle Detorie 312 John DeWitt 322 Diane Di Prima 326 Suzanne Doppelt 334 Paul Dresman 336 Aja Couchois Duncan 346 Camille Dungy 355 Marcella Durand 359 Martin Edmond 370 Sarah Tuss Efrik and Johannes Göransson 379 Tongo Eisen-Martin 397 Clayton Eshleman 404 Carrie Etter 407 Steven Farmer 409 Alec Finlay 421 Donna Fleischer 429 Evelyn Flores 432 Diane Gage 438 Jeannine Hall Gailey 442 Forrest Gander 448 Renée Gauthier 453 Crane Giamo 454 Giant Ibis 459 Alex Gildzen 460 Samantha Giles 461 C. -

The Self in the Song: Identity and Authority in Contemporary

The Self in the Song: Identity and Authority in Contemporary American Poetry by David William Lucas A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Linda K. Gregerson, Chair Professor Yopie Prins Associate Professor Gillian Cahill White Professor John A. Whittier-Ferguson for my teachers ii Acknowledgments My debts are legion. I owe so much to so many that I can articulate only a partial index of my gratitude here: To Jonathan Farmer and At Length, in which an adapted and excerpted version of “The Nothing That I Am: Mark Strand” first appeared, as “On Mark Strand, The Monument.” To Steven Capuozzo, Amy Dawson, and the Literature Department staff of the Cleveland Public Library for their assistance with my research. To the Department of English Language and Literature and the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan for the financial and logistical support that allowed me to begin and finish this project. To the Stanley G. and Dorothy K. Harris Fund for a summer grant that allowed me to continue my work without interruption. To the Poetry & Poetics Workshop at the University of Michigan, and in particular to Julia Hansen, for their assistance in a workshop of the introduction to this study. To my teachers at the University of Michigan, and especially to Larry Goldstein and Marjorie Levinson, whose interest in this project, support of it, and suggestions for it have proven invaluable. To June Howard, A. Van Jordan, Benjamin Paloff, and Doug Trevor. -

Ange Mlinko Associate Professor Department of English University of Florida [email protected]

Ange Mlinko Associate Professor Department of English University of Florida [email protected] Education M.F.A. (Creative Writing, Poetry) Brown University, Providence RI, 1998 B.A. (Philosophy and Mathematics) St. John’s College, Annapolis MD, 1991 Teaching Experience Term Professor (2018-2023), University of Florida Associate Professor (2014-present), Creative Writing Program, Department of English, University of Flor- ida Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference (2018), Poetry Faculty Assistant Professor (2010-14), Creative Writing Program, Department of English, University of Houston Courses Developed and Taught Rhetorical Tropes (graduate seminar) The Long Poem (graduate seminar) Modernism and Ancient Greek Poetry (graduate seminar) Poetry Workshop (graduate workshop) Master Workshop (graduate workshop) Advanced Poetry Workshop (undergraduate workshop) Poetic Forms (undergraduate workshop) Poetry Projects (undergraduate workshop) Awards Guggenheim Fellowship, 2014-15 Frederick Bock Prize, Poetry magazine, 2012 Randall Jarrell Award for Criticism, Poetry Foundation, 2009 Editor’s Prize for Reviewing, Poetry magazine, 2008 National Poetry Series, 2004 Publishers Weekly Best Books of 1999 The Fund for Poetry, 1996 and 2006 Starred Wire was one of two finalists for the James Laughlin Award in 2005. Shoulder Season was a finalist for the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America in 2010, and a finalist for a PEN Center USA award. Marvelous Things Overheard was named a “best book of poetry” on year-end lists in the New Yorker -

Wesleyan University Press Fall 2018

wesleyan university press fall 2018 Wesleyan University Press bury it sam sax Winner of the 2017 James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets sam sax’s bury it, winner of the 2017 James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets, begins with poems written in response to the spate of highly publicized young gay suicides in the summer of 2010. What follows are raw and expertly crafted meditations on death, desire, diaspora, and personhood. In this phenomenal second collection of poems, sam sax invites the reader to join him in his interrogation of the bridges we cross, the bridges we burn, and bridges we must leap from. “bury it is lit with imagery and purpose. A vitalizing and necessary book of poems.” September 2017 James Laughlin Award citation from 88 pp., 6 x 9" Judge Tyehimba Jess Paper, $14.95 • 978-0-8195-7731-3 (CAD 19.00) Ebook, $11.99 • 978-0-8195-7732-0 “Buried inside these turbulent and tragic elegies are the poetry sorrows so often borne in silence by queer or questioning youth. The unearthing and examination of these root causes Wesleyan Poetry of untimely death among at-risk kids forms a terrifying necrology, an urgent inquest into the violence perpetrated ,!7IA8B9-fhhdbd! by a society still harboring hostility toward otherness.” D. A. Powell “sam sax’s poems are stunning variations on desire and death in our post-postmodern era: desire as death, desire for death, the death of desire. Yet even as he buries our many lost to the ravages of AIDS and cancer and suicide, he resurrects them, in deeply moving elegies that reject sentimental praise, in reliving encounters with them that pulse with the erotic, in language that is at once plain and reverential. -

Rae Armantrout and Lisa Jarnot Readings in Contemporary Poetry Thursday, October 27, 2011, 6:30 Pm

Dia Art Foundation Rae Armantrout and Lisa Jarnot Readings in Contemporary Poetry Thursday, October 27, 2011, 6:30 pm Introduction by Vincent Katz Lisa Jarnot Lisa Jarnot was born in Buffalo, New York, in 1967. She studied with Robert Creeley at SUNY Buffalo (1992) and went on to earn an MFA from Brown (1994). Her first collection of poems, Some Other Kind of Mission (Burning Deck Press, 1996), was named an International Book of the Year in the Times Literary Supplement. She is the author of three other collections: Ring of Fire (Zoland Books, 2001 and Salt Publishers, 2003), Black Dog Songs (Flood Editions, 2003) and Night Scenes (Flood Editions, 2008). She co- edited An Anthology of New (American) Poetry(Talisman House Publishers, 1997). Ring of Fire begins with an epigraph from Catullus’ famous poem odi et amo… This quote is apposite, as Jarnot’s poetry holds within it an intense awareness of both romantic and erotic pain, albeit these sensations are often tossed off with a disarming casualness. Many of her poems make use of repeating rhythmic structures and a refrain-like use of rhyme, yet these materials are not used for their own sake, but are in the service of an ambitious project, incorporating memory, personal longing, environmental complaint, and social awareness. Complaint is a persistent tone in Jarnot’s poetry, a classic trope, which makes her a social, as well as a literary critic, but she leavens these grave burdens with humor. In “Ode” from Ring of Fire, she writes: For let me consider him who pretends to be the pizza delivery man and is instead the perfect part of day, for the fact he is a medium, for the eight to twelve inches of snow he tends to be… While often using the syntax of prose to reflect daily rumination, she introduces subtle shifts, which allow her to continue the rhythmic impulse of a piece until she chooses to close it. -

Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets

Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets Marit J. MacArthur, Georgia Zellou, and Lee M. Miller 04.18.18 Peer-Reviewed By: Jason Camlot & Anon. Clusters: Sound Article DOI: 10.22148/16.022 Dataverse DOI: 10.7910/DVN/FGNBHX Journal ISSN: 2371-4549 Cite: Marit J. MacArthur, Georgia Zellou, and Lee M. Miller, “Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets,”Cultural Analytics April 18, 2018. DOI: 10.22148/16.022. Literary readings provoke strong feelings, which feed intense critical de- bates.1And while recorded literary readings have long been available for study, 1This research was supported by a 2015-16 ACLS Digital Innovations Fellowship at the Univer- sity of California, Davis, and a grant from the Research Council of the University at California State University, Bakersfield in 2017, and it continues in 2018 with a NEH Digital Humanities Advance- ment grant (see http://textinperformance.soc.northwestern.edu/). Thanks to Hideki Kawahara for generously sharing TANDEM-STRAIGHT, to Dan Ellis for helping us set up his pitch-tracking al- gorithm in Matlab, to Robert Ochshorn and Max Hawkins for their development of the invaluable tools of Gentle and Drift that allowed much of the initial research to be undertaken, to the ModLab and the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of California, Davis, and to undergraduate research assistants Pavel Kuzkin and Richard Kim at UC Davis and Mateo Lara and David Stanley at CSU Bakersfield. Thanks also to Steve McLaughlin, Steve Evans, Christopher Grobe, and Mark Liberman for useful advice, and to the helpful audiences in Stanford’s Material Imagination: Sound, Space and Human Consciousness workshop series and at Cultural Analytics 2017 at the University of Notre Dame, where some of this research was presented. -

The Cambridge Companion to Twenty-First-Century American Poetry Edited by Timothy Yu Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48209-7 — The Cambridge Companion to Twenty-First-Century American Poetry Edited by Timothy Yu Frontmatter More Information the cambridge companion to twenty-first-century american poetry This Companion shows that American poetry of the twenty-first-century, while having important continuities with the poetry of the previous century, takes place in new modes and contexts that require new critical paradigms. Offering a comprehensive introduction to studying the poetry of the new century, this collection highlights the new, multiple centers of gravity that characterize American poetry today. Chapters on African American, Asian American, Latinx, and Indigenous poetries respond to the centrality of issues of race and indigeneity in contemporary American discourse. Other chapters explore poetry and feminism, poetry and disability, and queer poetics. The environment, capit- alism, and war emerge as poetic preoccupations, alongside a range of styles from the spoken word to the avant-garde, and an examination of poetry’s place in the creative writing era. Timothy Yu is the author of Race and the Avant-Garde: Experimental and Asian American Poetry since 1965, the editor of Nests and Strangers: On Asian American Women Poets, and the author of a poetry collection, 100 Chinese Silences. He is Martha Meier Renk-Bascom Professor of Poetry and Professor of English and Asian American Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University -

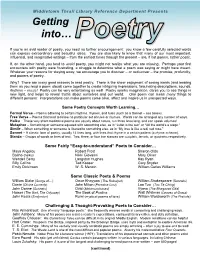

Getting Into Poetry

Middletown Thrall Library Reference Department Presents Getting into… If you’re an avid reader of poetry, you need no further encouragement: you know a few carefully selected words can express extraordinary and beautiful ideas. You are also likely to know that many of our most important, influential, and imaginative writings – from the earliest times through the present – are, if not poems, rather poetic. If, on the other hand, you tend to avoid poetry, you might not realize what you are missing. Perhaps your first encounters with poetry were frustrating, a struggle to determine what a poem was saying or might have meant. Whatever your reasons for staying away, we encourage you to discover – or rediscover – the promise, profundity, and powers of poetry. Why? There are many good reasons to read poetry. There is the sheer enjoyment of seeing words (and hearing them as you read a poem aloud) come together to create intriguing impressions, fascinating descriptions, sounds, rhythms – music! Poetry can be very entertaining as well! Poetry sparks imagination, dares you to see things in new light, and helps to reveal truths about ourselves and our world. One poem can mean many things to different persons: interpretations can make poems come alive, affect and inspire us in unexpected ways. Some Poetry Concepts Worth Learning… Formal Verse – Poems adhering to certain rhythms, rhymes, and rules (such as a Sonnet – see below). Free Verse – Poems that tend to follow no particular set of rules or rhymes. Words can be arranged any number of ways. Haiku – These very short meditative poems are usually about nature, run three lines long, and can speak volumes! Metaphor – Something or someone equated with something else, as in “Juliet is the sun” or “All the world’s a stage.” Simile – When something or someone is likened to something else, as in “My love is like a red, red rose.” Sonnet – A classic form of poetry, usually 14 lines long, with lines that rhyme in a certain pattern (a rhyme scheme). -

Safiya Sinclair & James Allen Hall | Mary Ruefle | Novembe

fall 2016 series | wednesdays | 7:00pm | tishman lecture hall SAFIYA SINCLAIR & JAMES ALLEN HALL | SEPTEMBER 21 | Safiya Sinclair is a graduate of Bennington College and the MFA Program at the University of Virginia, and presently a PhD candidate at the University of Southern California. Her poetry collection, Cannibal (University of Nebraska Press, 2016), won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Poetry, Poetry at Bennington is a Kenyon Review, Boston Review, the Iowa Review, Bennington Review, and elsewhere. Her writing has been honored with a Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center Fellowship, an series of readings, lectures, Amy Clampitt Residency Award, and a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation. and talks by prominent James Allen Hall is the author of the poetry collection Now You’re the Enemy (University of Arkansas Press), which received awards from the Lambda Literary Foundation, the American and internationally Texas Institute of Letters, and the Fellowship of Southern Writers. His lyric essay collection I Liked You Better Before I Knew You So Well won the Cleveland State University Poetry Center’s Essay Award and is forthcoming in 2017. His poetry has appeared in A Public Space, Bennington Review, Boston Review, and The Best American Poetry 2012. recognized poets which The recipient of fellowships from the NEA and the New York Foundation for the Arts, he teaches at Washington College in Chestertown, Maryland. takes place on the campus of Bennington College. It | | was established in 2012 MARY RUEFLE OCTOBER 5 with generous support from Mary Ruefle has authored numerous books of poetry, including Trances of the Blast (Wave, 2013), and Indeed I Was Pleased With the World (Carnegie Mellon, 2007). -

Don't Back Away: an Interview with Rae Armantrout

By Deborah Escalante and Calvin Pennix Don’t Back Away: An Interview with Rae Armantrout Rae Armantrout has been a part of the first generation of Language poetry in San Francisco since the 1970s. She has published ten books, and has also been featured in numerous anthologies. Armantrout won the 2009 National Book Critics Circle Award for her most recently published book, Versed, which was also awarded the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. She visited Chapman University on September 14, 2010 for the Poetry Reading Series. Deborah Escalante and Calvin Pennix: You won the 2009 National Book Critics Circle Award and the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for your book Versed. What were your initial reactions to being awarded these prestigious literary recognitions? Rae Armantrout: I was a bit overwhelmed. I didn’t realize how much media attention this particular prize receives. It seemed as if I spent weeks being interviewed in the newspaper, on the radio, and even by a couple of local television stations. Sometimes the interviewers knew something about poetry—but sometimes they didn’t. I didn’t watch the television morning show, but my husband tells me my clip came on right after a segment about farm animals. All this attention was briefly inhibiting and distracting, but that effect didn’t last long. I think I may be too old to change and also too old to take fame very seriously. Let’s just say I’ve seen the arc of a number of careers in my day. Escalante and Pennix: The use of language poetry seems to have had a recent resurgence—or at least visibility. -

A Speculative Essay About Poetry, Simile, Artificial

Like: A speculative essay about poetry, simile, artificial intelligence, mourning, sex, rock and roll, grammar, and romantic love, William Shakespeare, Alan Turing, Rae Armantrout, Nick Hornby, Walt Whitman, William Carlos Williams, Lia Purpura, and Claire Danes. The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Burt, Stephen. 2014. “Like: A speculative essay about poetry, simile, artificial intelligence, mourning, sex, rock and roll, grammar, and romantic love, William Shakespeare, Alan Turing, Rae Armantrout, Nick Hornby, Walt Whitman, William Carlos Williams, Lia Purpura, and Claire Danes.” American Poetry Review 43, no. 1: 17-21. Published Version http://old.aprweb.org/article/quotlikequot-speculative-essay-about- poetry-simile-artificial-intelligence-mourning-sex-rock Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:22686179 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP "LIKE" A speculative essay about poetry, simile, artificial intelligence, mourning, sex, rock and roll, grammar, and romantic love, William Shakespeare, Alan Turing, Rae Armantrout, Nick Hornby, Walt Whitman, William Carlos Williams, Lia Purpura, and Claire Danes [final version Nov. 2013] Poetry says— in however attenuated, confident or skeptical a fashion— "This is like that." Poetry in some accounts stands apart from other uses of language because it is only like those uses, its references only like (not a part of) the way that other uses of language point to things, or act on things, in the real world.