The Romani Archives and Documentation Center: a Migratory Archive?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Texas at Austin A0087 B0087

U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202-5335 APPLICATION FOR GRANTS UNDER THE National Resource Centers and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships CFDA # 84.015A PR/Award # P015A180087 Gramts.gov Tracking#: GRANT12659480 OMB No. , Expiration Date: Closing Date: Jun 25, 2018 PR/Award # P015A180087 **Table of Contents** Form Page 1. Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 e3 2. Standard Budget Sheet (ED 524) e6 3. Assurances Non-Construction Programs (SF 424B) e8 4. Disclosure Of Lobbying Activities (SF-LLL) e10 5. ED GEPA427 Form e11 Attachment - 1 (GEPA_427_MES_20181031746793) e12 6. Grants.gov Lobbying Form e13 7. Dept of Education Supplemental Information for SF-424 e14 8. ED Abstract Narrative Form e15 Attachment - 1 (Abstract_MES_20181031746782) e16 9. Project Narrative Form e17 Attachment - 1 (Narrative_MES_20181031746784) e18 10. Other Narrative Form e72 Attachment - 1 (Profile_Form_MES_20181031746785) e73 Attachment - 2 (Acronyms_Guide_MES_20181031746786) e74 Attachment - 3 (Higher_Ed_Act_Statutory_Requirements1031746787) e76 Attachment - 4 (Appendix_1_CV_and_position_descriptions_20181031746788) e79 Attachment - 5 (Appendix_2_Course_List_MES_20181031746789) e121 Attachment - 6 (Appendix_3_PMF_Appendix_Final1031746790) e137 Attachment - 7 (Appendix_4_Letters_of_Support_20181031746791) e140 11. Budget Narrative Form e142 Attachment - 1 (Budget_Narrative_MES_20181031746808) e143 This application was generated using the PDF functionality. The PDF functionality automatically numbers the pages in this application. Some pages/sections of this application may contain 2 sets of page numbers, one set created by the applicant and the other set created by e-Application's PDF functionality. Page numbers created by the e-Application PDF functionality will be preceded by the letter e (for example, e1, e2, e3, etc.). Page e2 OMB Number: 4040-0004 Expiration Date: 12/31/2019 Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 * 1. Type of Submission: * 2. -

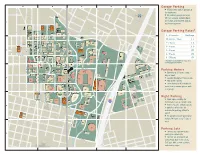

Parking Map for UT Campus

Garage Parking n Visitors may park in garages at the hourly rate n All parking garages are open 24/7 on a space-available basis for visitors and students and do not require a permit Garage Parking Rates* 0-30 minutes No Charge 30 minutes - 1 hour $ 3 1 - 2 hours $ 6 2 - 3 hours $ 9 3 - 4 hours $12 4 - 8 hours $15 8 - 24 hours $18 * Rates and availability may vary during special events. Parking Meters n Operational 24 hours a day, 7 days a week n Located throughout the campus n 25¢ for 15 minutes n Time limited to 45 minutes. If more time is needed, please park in a garage Night Parking n Read signs carefully for restrictions such as “At All Times” Bob B n ulloc After 5:45 p.m., certain spaces Texas k State Histo M ry useum in specific surface lots are available for parking without a permit n All garages provide parking for visitors 24 hours a day, 7 days a week Parking Lots n There is no daytime visitor parking in surface lots n Permits are required in all Tex surface lots from 7:30 a.m. to as Sta Ca te pitol 5:45 p.m. M-F as well as times indicated by signs BUILDING DIRECTORY CRD Carothers Dormitory .............................A2 CRH Creekside Residence Hall ....................C2 J R Public Parking CS3 Chilling Station No. 3 ...........................C4 JCD Jester Dormitory ..................................... B4 RHD Roberts Hall Dormitory .........................C3 CS4 Chilling Station No. 4 ...........................C2 BRG Brazos Garage .....................................B4 JES Beauford H. Jester Center ....................B3 RLM Robert Lee Moore Hall ..........................B2 CS5 Chilling Station No. -

Legend Garages

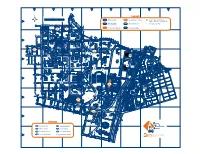

A B C D E F G H SAN SCALE: FEET Legend 0 500 250 500 JACINTO TPS Parking Garage Special Access Parking K Kiosk / Entry Control Station 1 (open 7:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. M-F) 2700 BLVD. Metered Parking Restricted Access Emergency Call Box 300W 200W 100W 100E 400W Active 24 hours W. 27TH ST. ARC FUTURE SITE Official Visitor Parking Construction Zone AVE. NRH TSG ST. SWG NOA AVE. SW7 LLF LLC CS5 BWY 2600 NSA LLE LLB 2600 2600 2600 LLD LLA 2600 CPE GIA KIN UA9 WICHITA ETC FDH NO PARKING SSB SEA WHITIS ST. 200E KEETON 500E 2 300W W. DEAN 200W 100W 100E KEETON ST. 300E 400E E. DEAN SHC 2500 ST. LTD NMS ECJ TNH ST. CMA RLM JON WWH CMB 2500 BUR 2500 SHD 2500 800E W. 25TH ST. CS4 600E CREEK CCJ UNIVERSITY CMC 2500 AHG MBB SPEEDWAY CTB DEV BLD WICHITA W 25th ST. CRD E. 500E 25th ST 900E LCH ENS . ST. SAG PHR PAT SER SJG AND 2400 DR. 2400 PHR SETON ANTONIO MRH MRH LFH ST. TCC CREEK 2400 GEA ESB WRW 2400 WOH SAN 300W K GRG 2400 1100E NUECES ST. W. 24th ST. E. 24th 300E ST. 2400 TMM K 200W 100W 100E 200E K E. DEAN E. 28th IPF YOUNG QUIST DA PPA BIO PAI ST. 3 ACE PPE Y DEDMAN KEETON WEL IT BOT WALLER IN 2300 R HMA BLVD. T 2300 PAC 200W 100W PPL ART LBJ PP8 NUECES ST. TAY ST. UNB FDF ST. DFA 1600E GEB CS2 ST. -

Faculty & Staff Parking

FACULTY & STAFF PARKING PARKING & TRANSPORTATION SERVICES | 15/16 FACULTY & STAFF PARKING to notify all permit holders of special CONTACT CONTENTS events that affect parking (see Special PTS MAIN OFFICE 02 Contact Events Calendar on PTS website). 1815 TRINITY ST. 02 Parking at UT Office Hours: FACULTY & STAFF 03 Permit/Parking Options M-F | 8 am–5 pm WITH DISABILITIES 04 Building Index Cashier Hours: PTS offers both annual “D” and temporary M-F | 8 am–7 pm 05 Campus Map “TD” permits for faculty/staff with permanent and temporary disabilities. Phone: 512-471-PARK (7275) 06 Citations, Booting & Appeals To obtain a “D” permit, faculty/staff must Fax: 512-232-9405 06 Driving & Parking Offenses bring a copy of their state ADA placard Mail: PO Box, Austin, TX 78713- 07 Green on the Go to any staffed garage office. If only an ADA license plate is available, the “D” 7546, Campus Mail D3000 08 Parking 101 permit must be purchased Monday Online: www.utexas.edu/parking through Friday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. If Twitter: utaustinparking PARKING AT UT the disability is temporary in nature , “TD” Located in the center of the city, The permits are issued at a rate of $12/month University of Texas at Austin campus is upon receipt of a letter or fax from the GARAGES often congested, making commuting applicant’s doctor stating the nature and Brazos Garage and parking difficult. Understanding duration of the temporary disability. 512-471-6126 (BRG) your parking and transportation options Alternative parking is provided for Conference Center and regulations will make campus “D” permit holders unable to locate 512-232-8314 Garage (CCG) access easier and promote safety. -

Board Meeting Minutes

Meeting No. 1,113 THE MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM Pages 1 - 92 November 14, 2013 Austin, Texas TABLE OF CONTENTS THE MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM NOVEMBER 14, 2013 AUSTIN, TEXAS MEETING NO. 1,113 Page No. November 14, 2013 I. ATTENDANCE 1 II. RECESS TO EXECUTIVE SESSION 1 III. RECESS FOR STANDING COMMITTEE MEETING AND RECONVENE IN OPEN SESSION 1 1. U. T. Austin: Authorization for the master development, ground leasing, and related partial sales pertaining to approximately 109 acres and improvements located at the southwest corner of West Braker Lane and North MoPac Expressway, Austin, Travis County, Texas, to Hines Interests Limited Partnership, a Delaware limited partnership, or a related entity, for commercial development purposes 2 2a. U. T. System Board of Regents: Discussion with Counsel on pending legal issues 2 2b. U. T. Austin: Authorization to implement assumption of loan agreements related to recruitment or retention programs administered by the Law School Foundation 2 2c. U. T. System Board of Regents: Discussion with Counsel and appropriate action regarding legal issues related to matters to be considered by the Select Committee on Transparency in State Agency Operations of the Texas House of Representatives 3 3a. U. T. Austin: Approval of proposed negotiated gifts with potential naming features 3 3b. U. T. Dallas: Approval of proposed negotiated gifts with potential naming features 3 i 3c. U. T. San Antonio: Approval of proposed negotiated gifts with potential naming features 3 3d. U. T. Tyler: Approval of proposed negotiated gifts with potential naming features 3 3e. -

Year Building Name Notes 1859 Arno Nowotny Building Arno Nowotny

The Daily Texan compiled the following spreadsheet and used it for "What's in a name?", the Rows highlighted red mean the building has been destroyed. Rows highlighted orange means the building was named after a UT president, faculty member or Rows highlighted green means the building was named after a donor. Rows highlighted light blue mean the building was named after an indivudual who was neither a Rows highlighted yellow means the building is an unnamed building, and might get named in the The sole row highlighted purple is the UT Tower and Main. The Main building will likely never be Year Building Name Notes Arno Nowotny Building was built in 1859, and then renamed in 1983 for a former dean of student life. It was not originally owned by the University, and it was formerly apart of the State Asylum for the 1859 Arno Nowotny Building Blind. The John W. Hargis Hall was renamed in 1983 for former special assistant to the president of the University. It was not originally owned by the University, and was formerly apart of the State 1888 John W. Hargis Hall Asylum for the Blind. 1889- The Old Main Building was destroyed in 1935 to be 1935 Old Main Building replaced by the new Main Building. The first power plant was destroyed in 1910 when the second power plant was constructed. The first 1889- power plant quickly became inadequate for 1910 First Power Plant supplying the campus with energy. B. Hall was the University's first dormitory. Originally built for just 58 students, B. -

Opens New Window

HINA AZAM Associate Professor, Islamic Studies Department of Middle Eastern Studies | The University of Texas at Austin Calhoun Hall 506 | 204 W. 21st Street | Austin, TX 78712 phone: 512.471.3881| email: [email protected] EDUCATION 2007 PhD, Islamic Studies, Department of Religion, Duke University, NC. Dissertation title: “Sexual Violence in Mālikī Legal Ideology: From Discursive Foundations to Classical Articulation” 2000 MA, Religion, Duke University, NC. Major: Islamic Studies (Islamic law) Internal Minor: Theories of Religion External Minor: Women and Gender Studies 1992 BA, Loyola University of Chicago, IL. Majors: Philosophy and Communication (Journalism) PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2015 – present Associate Professor, Islamic Studies, Department of Middle Eastern Studies, University of Texas at Austin. 2019 – present Graduate Advisor, Center for Middle Eastern Studies, University of Texas at Austin. 2016 - present Provost Teaching Fellow, University of Texas at Austin.* 2016 – present Editorial Board Member, The Modern Muslim World, Gorgias Press 2015 – 2019 Co-chair, Islamic Studies Initiative, University of Texas at Austin. 2015 – 2020 Book Review Editor, Journal of Law and Religion. Cambridge University Press. 2007 – 2014 Assistant Professor, Islamic Studies, Department of Middle Eastern Studies, University of Texas at Austin. 2009 – present Affiliations at University of Texas at Austin: Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Department of Religious Studies, and Center for Women’s and Gender Studies. * “Teaching the University” Canvas Curriculum. Page 1 of 15 1999 – 2004 Lecturer, Islamic Studies, Department of Religious Studies, St. Mary’s College of California, CA. 2002 - 2003 Anderson Visiting Instructor in Religious Studies, Department of Religious Studies, Stanford University, CA. PUBLICATIONS Books Sexual Violation in Islamic Law: Substance, Evidence and Procedure. -

Capital Expenditure Plans FY 2010 to FY 2014

Capital Expenditure Plans FY 2010 to FY 2014 August 2009 Division of Planning and Accountability Finance and Resource Planning Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board A.W. “Whit” Riter III, CHAIR Tyler Fred W. Heldenfels IV, VICE CHAIR Austin Elaine Mendoza, SECRETARY OF THE BOARD San Antonio Heather A. Morris, STUDENT REPRESENTATIVE Lubbock Laurie Bricker Houston Joe B. Hinton Crawford Brenda Pejovich Dallas Lyn Bracewell Phillips Bastrop Robert V. Wingo El Paso Raymund A. Paredes, COMMISSIONER OF HIGHER EDUCATION Mission of the Coordinating Board The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board’s mission is to work with the Legislature, Governor, governing boards, higher education institutions and other entities to help Texas meet the goals of the state’s higher education plan, Closing the Gaps by 2015, and thereby provide the people of Texas the widest access to higher education of the highest quality in the most efficient manner. Philosophy of the Coordinating Board The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board will promote access to quality higher education across the state with the conviction that access without quality is mediocrity and that quality without access is unacceptable. The Board will be open, ethical, responsive, and committed to public service. The Board will approach its work with a sense of purpose and responsibility to the people of Texas and is committed to the best use of public monies. The Coordinating Board will engage in actions that add value to Texas and to higher education. The agency will avoid efforts that do not add value or that are duplicated by other entities. The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, or disability in employment or the provision of services. -

UT Student Kills Self a Er Firing AK-47 on 21St Street Witnesses Recount

1 HE AILY EXAN TWednesday, September 29, 2010 DServing the University of Texas at Austin community since 1900T www.dailytexanonline.com Gunman terrorizes campus UT student kills self a er firing AK-47 on 21st Street By Nolan Hicks Daily Texan Staff The UT campus was on lockdown for nearly four hours Tuesday because of a shooting incident that ended when the gunman, armed with an AK-47 rifle, took his own life after unleashing a barrage of bullets and being cornered by police on the sixth floor of the Per- ry-Castañeda Library. Campus admin- ON THE WEB: istrators identified Video recap of the the gunman as day’s events 19-year-old mathe- matics sophomore @dailytexan Colton Tooley. online.com A half-dozen law enforcement agencies, including the Austin Police Department, University of Texas Police Department, the Texas Department of Public Safety and the Austin Independent School Dis- trict Police Department, responded to the shooting and its aftermath. Officials said no students were hurt in the shooting, although a couple of stu- dents were mildly injured during the evacuation process. “I am grateful to our campus commu- nity for the way it responded to the emer- gency that took place at the Perry-Casta- Tamir Kalifa | Daily Texan Staff ñeda Library [Tuesday] morning,” UT Austin police prepare to enter Calhoun Hall on the South Mall on Tuesday morning after a gunman opened fire near the Littlefield Fountain and later fatally shot himself on the sixth floor of the Perry-Castañeda Library. Austin Police Department and SWAT officers suspected an additional gunman was in Calhoun Hall but quickly determined the shooter acted alone. -

Facilities Planning and Construction Committee

Meeting of the U. T. System Board of Regents - Facilities Planning and Construction Committee TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR FACILITIES PLANNING AND CONSTRUCTION COMMITTEE Committee Meeting: 11/14/2013 Board Meeting: 11/14/2013 Austin, Texas Alex M. Cranberg, Chairman Ernest Aliseda R. Steven Hicks Wm. Eugene Powell Robert L. Stillwell Committee Board Page Meeting Meeting Convene 1:00 p.m. Chairman Cranberg 1. U. T. System Board of Regents: Discussion and appropriate 1:00 p.m. action regarding Consent Agenda items, if any, referred for Action Action 132 Committee consideration Reports 2. U. T. System: Fiscal Year 2013 Energy Utility Task Force 1:00 p.m. Report Report/Discussion Not on 133 Mr. O'Donnell Agenda 3. U. T. System: Update on Space Utilization Efficiency 1:06 p.m. Report/Discussion Not on 134 Mr. O'Donnell Agenda 4. U. T. System: Update on progress of the new University of 1:10 p.m. Texas in South Texas Campus Master Plan Engagement Report/Discussion Not on 135 Mr. O'Donnell Agenda Additions to the CIP 5. U. T. Austin: Tennis Center Replacement Facility - Amendment 1:14 p.m. of the FY 2014-2019 Capital Improvement Program to include Action Action 136 project (Preliminary Board approval) President Powers 6. U. T. San Antonio: Recreation Center Pool Reconstruction - 1:18 p.m. Amendment of the FY 2014-2019 Capital Improvement Action Action 137 Program to include project; approval of total project cost; Mr. O'Donnell appropriation of funds; authorization of institutional management; and resolution regarding parity debt (Final Board approval) 130 Meeting of the U. -

Visitor-Map.Pdf

A B C D E Guadalupe Street East 30 th Visitors Map Street USS Duval Street 1 27th Street ARC Kiosk Food ADH IC2 SWG CPB TSG NOA SW7 LLC CS5 BWY Whichita St. CEE Parking Parking Nueces Street LLE LLB UA9 LLD LLA Garage Meter Speedway Whitis Ave. CPE Park Place th KIN University Ave. West 26 Street BMC ETC SSB SEA FDH Garage Parking West Dean Keeton Street East Dean Keeton Street Medical Arts Street BME NMS • Visitors may park in garages CMA LTD ECJ TNH RLM . CRH CS4 JON WWH d BUR v l East 30 at the hourly rate CMB B th East Dean Keeton Street th West 25 Street CRD o CCJ t Street HSM n HSS MBB i c th a • All parking garages are open W 25 Street BLD J DEV East 25th Street University Ave. EERC n AHG a LCH S 24/7 on a space-available SAG AND PHR PAT SER 2 LFH FNT SJG MRH basis for visitors and students Nueces Street GEA NHB ESS TCC Guadalupe Street GWB WRW Robinson Ave. San Antonio Street and do not require a permit West 24th Street East 24th Street TMM Trinity Street Trinity IPF BIO PAI PPA East Dean Keeton Street POB PPE PAC Garage Parking Rates* HMA BOT WEL GDC CS6 PPL LBJ FC8 UNB ART Red River Street GEB DFA Robert Dedman Drive Speedway JGB WIN AFP 0−30mins No Charge FAC WCH EPS FC3 MAI LTH 30mins−1hr $ 3 COM WAG East 23rd Street SRH FC4 BTL BRB WMB GAR CLA FC2 1−2hrs $ 6 GOL NEZ Chicon Street SAC FC9 Inner Campus Drive FC5 Salina Street 2−3hrs $ 9 SUT PAR BAT UTX UPB FC6 Leona Street Clyde Littlefield Drive FC7 UIL CAL MEZ CBA Manor Road 3−4hrs $ 12 GSB BEL STD 3 HRC GRE CDA CML HRH BEN MHD nd Street 4−8hrs $ 15 East 22 West 21st Street East 21st Street MSB MAG MMS Concho St. -

UT System Annual Executive Order RP-49 January 2014

EXECUTIVE ORDER RP-49 Annual Report for UT System – January 2014 By January 2014, each agency shall submit an Update to its Energy Conservation Plan to the Office of the Governor and Legislative Budget Board. This update shall, at a minimum, provide the following information: A. The extent to which the agency has met the percentage goal it established for reducing its usage of electricity, gasoline, and natural gas; UT System Response: The UT System has been collecting extensive energy data from its 15 institutions on an annual basis since 2001. In 2001, the Board of Regents established a goal of reducing energy consumption by 10-15% by the end of FY 2011. From FY 2002-FYE 2011, the UT System had reduced overall energy consumption by 18.0%, saving an estimated $250 million. On November 10, 2011 the UT System Board of Regents approved extending the 2001 baseline energy consumption reduction goals an additional 5% - 10% through 2021. From FY 2002-FYE 2013, the UT System had reduced overall energy consumption by 25.0%, saving an estimated $417 million. B. The steps the agency may take to increase the percentage goal for reducing its usage of electricity, gasoline, and natural gas; UT System Response: The UT System reported its energy conservation goals in December 2005. These goals already include a “stretch” goal of reducing energy consumption per square foot by 10 – 15% as of FYE 2011. The UT System extended these goals an additional 5% - 10% through 2021. C. Any additional ideas the agency has for reducing energy expenditures relating to facilities; (See attached information.) D.