The Rank and File Movement in Social Work, 1931-1950

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Fear Is Substituted for Reason: European and Western Government Policies Regarding National Security 1789-1919

WHEN FEAR IS SUBSTITUTED FOR REASON: EUROPEAN AND WESTERN GOVERNMENT POLICIES REGARDING NATIONAL SECURITY 1789-1919 Norma Lisa Flores A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2012 Committee: Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Dr. Mark Simon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Brooks Dr. Geoff Howes Dr. Michael Jakobson © 2012 Norma Lisa Flores All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Although the twentieth century is perceived as the era of international wars and revolutions, the basis of these proceedings are actually rooted in the events of the nineteenth century. When anything that challenged the authority of the state – concepts based on enlightenment, immigration, or socialism – were deemed to be a threat to the status quo and immediately eliminated by way of legal restrictions. Once the façade of the Old World was completely severed following the Great War, nations in Europe and throughout the West started to revive various nineteenth century laws in an attempt to suppress the outbreak of radicalism that preceded the 1919 revolutions. What this dissertation offers is an extended understanding of how nineteenth century government policies toward radicalism fostered an environment of increased national security during Germany’s 1919 Spartacist Uprising and the 1919/1920 Palmer Raids in the United States. Using the French Revolution as a starting point, this study allows the reader the opportunity to put events like the 1848 revolutions, the rise of the First and Second Internationals, political fallouts, nineteenth century imperialism, nativism, Social Darwinism, and movements for self-government into a broader historical context. -

Charles Ensley Scholarship Fund Dinner Charles Ensley Earned His Right to Be a Part of the Labor Relations History of Our Country

January 23, 2014 Robert Croghan Charles Ensley Scholarship Fund Dinner Charles Ensley earned his right to be a part of the labor relations history of our country. That story goes back to before Charles was born. In 1912, the Lloyd-La Follette Act allowed government workers to belong to a union. By 1917, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) had chartered a national government workers union for federal employees, and, in 1936, the AFL chartered the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. By 1937, the left wing of AFSCME, led by public sector Caseworker unions, broke off from AFSCME and joined the Congress of Industrial Organizations. After a number of splits and mergers, in 1946, the United Public Workers of America became the dominant union for NYC Caseworkers and Public Hospital Workers. It was also the largest public employee union in the country. That was the high point. Thereafter, between 1946 and 1953, Congress and the nation at large became consumed by the red scare. The United Public Workers of America was a casualty of that period of anti-communist hysteria. It was sad because the UPWA was a militant union that had taken strong stands against racism and disparities in pay based on the sex of the employee, and was in favor of public service workers in general. The first African American woman to lead a union in New York was Eleanor Godling of the UPWA. She also served on the National Board of the CIO. The last President of the UPWA, Abram Flaxer, was sent to jail in 1953. -

The History Books Tell It? Collective Bargaining in Higher Education in the 1940S

Journal of Collective Bargaining in the Academy Volume 9 Creating Solutions in Challenging Times Article 3 December 2017 The iH story Books Tell It? Collective Bargaining in Higher Education in the 1940s William A. Herbert Hunter College, City University of New York, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/jcba Part of the Collective Bargaining Commons, Higher Education Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Labor History Commons, Legal Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Herbert, William A. (2017) "The iH story Books Tell It? Collective Bargaining in Higher Education in the 1940s," Journal of Collective Bargaining in the Academy: Vol. 9 , Article 3. Available at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/jcba/vol9/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Collective Bargaining in the Academy by an authorized editor of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The iH story Books Tell It? Collective Bargaining in Higher Education in the 1940s Cover Page Footnote The er search for this article was funded, in part, by a grant from the Professional Staff onC gress-City University of New York Research Award Program. Mr. Herbert wishes to express his appreciation to Tim Cain for directing him to archival material at Howard University, and to Hunter College Roosevelt Scholar Allison Stillerman for her assistance with the article. He would also like to thank the staff ta the following institutions for their prompt and professional assistance: New York State Library and Archives; Tamiment Library and Robert F. -

The Sedition Trial

NOTES Yet either view, consistently applied, would provide jury trials in constructive criminal contempt cases. Under both theories, due process requires different procedural safeguards in different situations: a prosecution which fulfils the demands of due process in punishing a direct contempt may not suffice if the alleged contempt was committed out of court. 34 Justice Cardozo, expressing the majority rationale, has suggested that ... we reach a different plane of social and moral values when we pass to the privileges and immunities that have been taken over from the earlier articles of the federal bill of rights and brought within the Fourteenth Amendment by a process of absorption. These in their origin were effective against the federal government alone. If the Four- teenth Amendment has absorbed them, the process of absorption has had its source in the belief that neither liberty nor justice would exist if they were sacrificed.' X3s If this is so, then the climb of our "social and moral values" has been a slow one indeed; even the basic right of freedom of speech was only "absorbed" by the Fourteenth Amendment fifty-seven years after its adop- tion.z36 Admittedly, the denial of jury trial in one class of contempt cases is not of the same broad sweep as the denial of free speech or a free press; perhaps it does not stand on the same plane in the scale of civil liberties. But Justice Cardozo's analysis is not exclusive. Unyielding application of the "inherent power" and "immemorial usage" doctrine by state courts has thwarted all legislative at- tempts to abolish summary proceedings in indirect contempts. -

Biographyelizabethbentley.Pdf

Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 1 of 284 QUEEN RED SPY Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 2 of 284 3 of 284 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet RED SPY QUEEN A Biography of ELIZABETH BENTLEY Kathryn S.Olmsted The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill and London Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 4 of 284 © 2002 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet The University of North Carolina Press All rights reserved Set in Charter, Champion, and Justlefthand types by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Olmsted, Kathryn S. Red spy queen : a biography of Elizabeth Bentley / by Kathryn S. Olmsted. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-8078-2739-8 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Bentley, Elizabeth. 2. Women communists—United States—Biography. 3. Communism—United States— 1917– 4. Intelligence service—Soviet Union. 5. Espionage—Soviet Union. 6. Informers—United States—Biography. I. Title. hx84.b384 o45 2002 327.1247073'092—dc21 2002002824 0605040302 54321 Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 5 of 284 To 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet my mother, Joane, and the memory of my father, Alvin Olmsted Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 6 of 284 7 of 284 Contents Preface ix 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet Acknowledgments xiii Chapter 1. -

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England. -

Rachel Sheridan CV Oct 2019

RACHEL SHERIDAN http://www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk/casting-director/rachel-sheridan/ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm4730933/?ref_=fn_al_nm_1 Tel: +44 (0) 203 405 7431 / +44 (0) 7793003462 Email: [email protected] Representation: Hamilton Hodell – Maddie Dewhirst & Sian Smyth [email protected] & [email protected] 020 7636 1221 • CASTING DIRECTOR Drama IN MY SKIN Series 1 & 2 Comedy/Drama: Expectation Entertainment for BBC & BBC Wales By Kayleigh Llewellyn Director: Lucy Forbes • RTS 2021 Winner – Best Drama Producer: Nerys Evans/Sophie Francis Series • BAFTA Cymru 2019 Winner - Best Drama & Best Actress • RTS Cymru 2020 Winner – Best Drama THE LEFT BEHIND Drama: BBC Studios for BBC Wales & BBC 3 By Alan Harris Director: Joseph Bullman • RTS 2020 Winner – Best Single Exec Producer: Aysha Rafaele Drama Producer: Tracie Simpson • BAFTA 2020 Winner – Best Single Drama • BAFTA Cymru 2020 Winner – Best Drama FLACK Series 1 & 2 Drama: Hat Trick for UKTV & POP By Oli Lansley Director: Peter Cattaneo & George Kane (series 1) Alicia MacDonald, Oliver Lansley, Stephen Moyer (series 2) Producer: Mark Talbot (series 1) Debbie Pisani (series 2) BLACK MIRROR – HATED IN THE Drama: Black Mirror Drama Ltd for Netflix NATION (Child Casting Director) Director: James Hawes By Charlie Brooker Producer: Sanne Wohlenberh Comedy I HATE YOU Comedy Series: Big Talk for CH 4 By Robert Popper Director: Damon Beesely Producer: Robert Popper & Lynn Roberts BIG BOYS Comedy Series: Roughcut for CH 4 By Jack Rooke Director: Jim Archer Producer: -

BRITISH ACADEMY TELEVISION CRAFT AWARDS in 2016: Winners in *BOLD

BRITISH ACADEMY TELEVISION CRAFT AWARDS IN 2016: Winners in *BOLD SPECIAL AWARD *NINA GOLD BREAKTHROUGH TALENT sponsored by Sara Putt Associates DC MOORE (Writer) Not Safe for Work- Clerkenwell Films/Channel 4 GUILLEM MORALES (Director) Inside No. 9 - The 12 Days of Christine - BBC Productions/BBC Two MARCUS PLOWRIGHT (Director) Muslim Drag Queens - Swan films/Channel 4 *MICHAELA COEL (Writer) Chewing Gum - Retort/E4 COSTUME DESIGN sponsored by Mad Dog Casting BARBARA KIDD Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell - Cuba Pictures/Feel Films/BBC One *FOTINI DIMOU The Dresser - Playground Television UK Limited, Sonia Friedman Productions, Altus Productions, Prescience/BBC Two JOANNA EATWELL Wolf Hall - Playground Entertainment, Company Pictures/BBC Two MARIANNE AGERTOFT Poldark - Mammoth Screen Limited/BBC One DIGITAL CREATIVITY ATHENA WITTER, BARRY HAYTER, TERESA PEGRUM, LIAM DALLEY I'm A Celebrity... Get Me Out of Here! - ITV Consumer Ltd *DEVELOPMENT TEAM Humans - Persona Synthetics - Channel 4, 4creative, OMD, Microsoft, Fuse, Rocket, Supernatural GABRIEL BISSET-SMITH, RACHEL DE-LAHAY, KENNY EMSON, ED SELLEK The Last Hours of Laura K - BBC MIKE SMITH, FELIX RENICKS, KIERON BRYAN, HARRY HORTON Two Billion Miles - ITN DIRECTOR: FACTUAL ADAM JESSEL Professor Green: Suicide and Me - Antidote Productions/Globe Productions/BBC Three *DAVE NATH The Murder Detectives - Films of Record/Channel 4 JAMES NEWTON The Detectives - Minnow Films/BBC Two URSULA MACFARLANE Charlie Hebdo: Three Days That Shook Paris - Films of Record/More4 DIRECTOR: FICTION sponsored -

Immigrants and Counterterrorism Policy: a Comparative Study of the United States and Britain

IMMIGRANTS AND COUNTERTERRORISM POLICY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE UNITED STATES AND BRITAIN A dissertation presented by David Michael Smith to The Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science Northeastern University Boston, MA April 2013 1 IMMIGRANTS AND COUNTERTERRORISM POLICY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE UNITED STATES AND BRITAIN by David Michael Smith ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate School of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2013 2 Abstract This project examines the political mechanisms through which foreign nationals are perceived as security threats and, as a consequence, disproportionately targeted by counterterrorism policies. Evidence suggests that domestic security strategies that unduly discriminate against non-citizens or national minorities are counterproductive; such strategies lead to a loss of state legitimacy, they complicate the gathering of intelligence, and they serve as a potential source of radicalization. At the same time, discriminatory counterterrorism policies represent a significant break from liberal democratic ideals by legitimizing unfair treatment of targeted groups. If discriminatory counterterrorism policies are counterproductive and undemocratic, why do policymakers support such strategies in the first place? By what means do these types of policies and related administrative measures gain traction in the political system? How do these measures operate in practice, and what accounts for variations in their implementation over time? To answer these questions, a policy process model is used that distinguishes between the problem definition and agenda setting, policy formulation and legitimation, and policy implementation phases of policymaking. -

Anti-Communism in Twentieth-Century America

Anti-Communism in Twentieth-Century America Anti-Communism in Twentieth-Century America A Critical History Larry Ceplair Copyright 2011 by Larry Ceplair All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ceplair, Larry. Anti-communism in twentieth-century America / Larry Ceplair. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978 1 4408 0047 4 (hardcopy : alk. paper) ISBN 978 1 4408 0048 1 (ebook) 1. Anti-communist movements United States History 20th century. 2. Political culture United States History 20th century. 3. Political activists United States Biography. 4. United States Politics and government 1919 1933. 5. United States Politics and government 1933 1945. 6. United States Politics and government 1945 1989. I. Title. E743.5.C37 2011 973.91 dc23 2011029101 ISBN: 978 1 4408 0047 4 EISBN: 978 1 4408 0048 1 1514131211 12345 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. Praeger An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America To Christine, the love of my life and the source of my happiness. Contents Introduction -

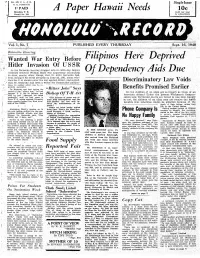

Honolulu Rfcord

I? Sec. 562, P. L. & R. Single Issue U. S. POSTAGE BPAID A Paper Hawaii Needs 10c Honolulu, T. H. $5.00: per year Permit No. 189 by subscription' ’ HONOLUlU RfCORD Vol.1, No. 7 PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY Sept. 16, 1948 11 einecke IIearing Wanted War Entry Before Filipinos Here Deprived Hitler Invasion Of USSR . ' As the Reinecke hearing dragged into its 30th day Deputy Attorney General William Blatt was apparently attempting Of Dependency Aids Due to show', among other /.things, that Dr. John Reinecke had, first, changed his mind abruptly Qn June 22, 1941, about whe ther the U. S, should enter the war- against Hitler, and second, Discriminatory Law Voids that Dr. Reinecke had been a writer for Communist publica- : - . tions. In neither effort was he. es- pecially successful. t. : Dr., llchiccke said that during the “Bitter Joke” Says Benefits Promised Eafiier /'’ period of the “phony war,” he had Do the children of an alien get as hungry as those of an ’ _ ^opposed IT. S. aid to. Britain, but Bishop Of T-H Act ./ that he had “changed his mind /. American citizen? Under the; present - Workmen’s Compen- i gradually” until , he had come to “The balance of power was al- / sation Law, Territorial courts are forced to rule that, hungry I ' favor U. S. action against Germany ways with. management and the / Dr not, the children of an alien may not receive the dekith i : some. months before the. Nazi inva- Taft-Hartley Act has only in j® benefits that otherwise might be awarded because of the ' sioh of the USSR. -

Recent Studies in Canadian Labour History from the Great Depression

Document generated on 09/24/2021 12:38 p.m. Labour Journal of Canadian Labour Studies Le Travail Revue d’Études Ouvrières Canadiennes Recent Studies in Canadian Labour History from the Great Depression into the 21st Century Stephen Endicott, Raising the Workers’ Flag: The Workers’ Unity League of Canada, 1930–1936 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012) Wendy Cuthbertson, Labour Goes to War: The CIO and the Construction of a New Social Order, 1939–1945 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2012) Jason Russell, Our Union: UAW/CAW Local 27 from 1950 to 1990 (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2011) Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage, Union Power: Solidarity and Struggle in Niagara (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2012) David Camfield Forum: History Under Harper Volume 73, Spring 2014 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1025202ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian Committee on Labour History ISSN 0700-3862 (print) 1911-4842 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this note Camfield, D. (2014). Recent Studies in Canadian Labour History from the Great Depression into the 21st Century / Stephen Endicott, Raising the Workers’ Flag: The Workers’ Unity League of Canada, 1930–1936 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012) / Wendy Cuthbertson, Labour Goes to War: The CIO and the Construction of a New Social Order, 1939–1945 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2012) / Jason Russell, Our Union: UAW/CAW Local 27 from 1950 to 1990 (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2011) / Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage, Union Power: Solidarity and Struggle in Niagara (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2012). Labour / Le Travail, 73, 239–254. All Rights Reserved © Canadian Committee on Labour History, 2014 This document is protected by copyright law.