Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from the Online Library of the International Society for Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ISSMGE)

INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR SOIL MECHANICS AND GEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING This paper was downloaded from the Online Library of the International Society for Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ISSMGE). The library is available here: https://www.issmge.org/publications/online-library This is an open-access database that archives thousands of papers published under the Auspices of the ISSMGE and maintained by the Innovation and Development Committee of ISSMGE. 5/1 Some geotechnical aspects of the marls of Corinth Canal Quelques aspects geotechniques des marnes du canal de Corinthe A.ANAGNOSTOPOULOS, Ass. Professor, Technical University of Athens, Greece ST.CHRISTOULAS, Ass. Professor, Technical University of Athens, Greece N.KALTEZIOTIS, Public Works Research Center, Athens, Greece G.TSIAMBAOS, Public Works Research Center, Athens, Greece SYNOPSIS: The Corinth Canal is of great importance regarding the navigation in the Mediterranean Sea and the railway and roadway transportation between Peloponnese and the Central Greece. For a better understanding of the mechanical behaviour of the marls, found in abundance in the narrow zone of the Corinth Canal, investigations of laboratory and in situ testing have been carried out including: Dril ling of boreholes and sampling; laboratory testing (determination of Atterberg limits, unconfined and triaxial compression tests, residual shear strength characteristics of the different types of marls involved, consolidation tests, etc.); mineralogical analysis by using X-Ray diffraction techniques and electronic microscopy. In this paper after considering the Engineering geological aspects of the area, results of the tests described above are presented and critically discussed, some correlations are given and some comparisons with marls from other areas of Greece are considered. -

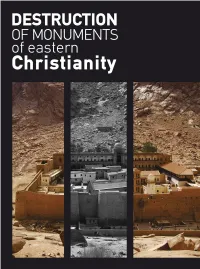

Monuments.Pdf

© 2017 INTERPARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY ON ORTHODOXY ISBN 978-960-560 -139 -3 Front cover page photo Sacred Monastery of Mount Sinai, Egypt Back cover page photo Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, Kiev, Ukrania Cover design Aristotelis Patrikarakos Book artwork Panagiotis Zevgolis, Graphic Designer, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Editing George Parissis, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | International Affairs Directorate Maria Bakali, I.A.O. Secretariat Lily Vardanyan, I.A.O. Secretariat Printing - Bookbinding HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Οι πληροφορίες των κειμένων παρέχονται από τους ίδιους τους διαγωνιζόμενους και όχι από άλλες πηγές The information of texts is provided by contestants themselves and not from other sources ΠΡΟΛΟΓΟΣ Η προστασία της παγκόσμιας πολιτιστικής κληρονομιάς, υποδηλώνει την υψηλή ευθύνη της κάθε κρατικής οντότητας προς τον πολιτισμό αλλά και ενδυναμώνει τα χαρακτηριστικά της έννοιας “πολίτης του κόσμου” σε κάθε σύγχρονο άνθρωπο. Η προστασία των θρησκευτικών μνημείων, υποδηλώνει επί πλέον σεβασμό στον Θεό, μετοχή στον ανθρώ - πινο πόνο και ενθάρρυνση της ανθρώπινης χαράς και ελπίδας. Μέσα σε κάθε θρησκευτικό μνημείο, περι - τοιχίζεται η ανθρώπινη οδύνη αιώνων, ο φόβος, η προσευχή και η παράκληση των πονεμένων και αδικημένων της ιστορίας του κόσμου αλλά και ο ύμνος, η ευχαριστία και η δοξολογία προς τον Δημιουργό. Σεβασμός προς το θρησκευτικό μνημείο, υποδηλώνει σεβασμό προς τα συσσωρευμένα από αιώνες αν - θρώπινα συναισθήματα. Βασισμένη σε αυτές τις απλές σκέψεις προχώρησε η Διεθνής Γραμματεία της Διακοινοβουλευτικής Συνέ - λευσης Ορθοδοξίας (Δ.Σ.Ο.) μετά από απόφαση της Γενικής της Συνέλευσης στην προκήρυξη του δεύτερου φωτογραφικού διαγωνισμού, με θέμα: « Καταστροφή των μνημείων της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής ». Επι πλέον, η βούληση της Δ.Σ.Ο., εστιάζεται στην πρόθεσή της να παρουσιάσει στο παγκόσμιο κοινό, τον πολιτισμικό αυτό θησαυρό της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής και να επισημάνει την ανάγκη μεγαλύτερης και ου - σιαστικότερης προστασίας του. -

VISIONS ACADEMY! Outstanding ‘Performing & Expressive Arts’ School Trips for Drama, Dance, Music and Art Groups

Tour: Academy in Greece Destination: Poros, Greece with excursions to Athens, Epidaurus, Nafplio & Corinth Canal Specialization: Drama & Music; Workshop-based Itinerary: 5-days / 4-nights in destination Academy in Greece - Sample Itinerary Morning Afternoon Evening 1 Travel to Athens, excursion to Corinthian Canal, transfer to the Island of Poros Welcome Dinner 2 Breakfast Master Class 1 Lunch Master Class 2 Master Class 3 Dinner 3 Breakfast Classical Tour Day Trip - Nafplio & Epidaurus Dinner & Greek Dancing Evening 4 Breakfast Master Class 4 Master Class 5 Lunch Free Time Dinner 5 Breakfast Athens Excursion Fly Home Welcome to world of VISIONS ACADEMY! Outstanding ‘Performing & Expressive Arts’ school trips for Drama, Dance, Music and Art groups. With our destinations around the world you’ll find workshop-based trips, performance-based trips, and combination trips. From New York to China, Greece to Costa Rica, Spain to Hollywood… let us take you on a trip your students will remember for a lifetime! Welcome to Visions Academy! As with all sample itineraries, please be advised that this is an ‘example’ of a schedule and that the activities and hotels shown may be variable dependent upon dates, weather, special requests and other factors. Itineraries will be confirmed prior to travel. Greece… Visions Academy offers the delights of the Greek mainland and the culturally rich region of the Peloponnese all wrapped up in one fantastic tour. Here, our groups are offered a wealth of culture matched only by the spectacular landscape, lapped by sparkling blue seas and covered in lemon groves. Greece produced some of the greatest philosophers, artists and poets of the ancient world and this unique trip enables students to take a step back in time and appreciate this mythical country. -

Fonds Gabriel Deville (Xviie-Xxe Siècles)

Fonds Gabriel Deville (XVIIe-XXe siècles) Répertoire numérique détaillé de la sous-série 51 AP (51AP/1-51AP/9) (auteur inconnu), révisé par Ariane Ducrot et par Stéphane Le Flohic en 1997 - 2008 Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 1955 - 2008 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_001830 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé en 2012 par l'entreprise Numen dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales 2 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Référence 51AP/1-51AP/9 Niveau de description fonds Intitulé Fonds Gabriel Deville Date(s) extrême(s) XVIIe-XXe siècles Nom du producteur • Deville, Gabriel (1854-1940) • Doumergue, Gaston (1863-1937) Importance matérielle et support 9 cartons (51 AP 1-9) ; 1,20 mètre linéaire. Localisation physique Pierrefitte Conditions d'accès Consultation libre, sous réserve du règlement de la salle de lecture des Archives nationales. DESCRIPTION Type de classement 51AP/1-6. Collection d'autographes classée suivant la qualité du signataire : chefs d'État, gouvernants français depuis la Restauration, hommes politiques français et étrangers, écrivains, diplomates, officiers, savants, médecins, artistes, femmes. XVIIIe-XXe siècles. 51AP/7-8. Documents divers sur Puydarieux et le département des Haute-Pyrénées. XVIIe-XXe siècles. 51AP/8 (suite). Documentation sur la Première Guerre mondiale. 1914-1919. 51AP/9. Papiers privés ; notes de travail ; rapports sur les archives de la Marine et les bibliothèques publiques ; écrits et documentation sur les départements français de la Révolution (Mont-Tonnerre, Rhin-et-Moselle, Roer et Sarre) ; manuscrit d'une « Chronologie générale avant notre ère ». -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/191455 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2018-06-17 and may be subject to change. THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE HUMANITIES Ideals and Practices of Scholarship between Enlightenment and Romanticism, 1750 – 1850 Floris Solleveld The Transformation of the Humanities The Transformation of the Humanities Ideals and Practices of Scholarship between Enlightenment and Romanticism, 1750-1850 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. J.H.J.M. van Krieken, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 9 april 2018 om 16:30 precies door Floris Otto Solleveld geboren op 9 juli 1982 te Amsterdam Promotoren: Prof. dr. Peter Rietbergen Prof. dr. Rens Bod (Universiteit van Amsterdam) Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. Alicia Montoya Prof. dr. Christoph Lüthy Prof. dr. Joep Leerssen (Universiteit van Amsterdam) Prof. dr. Wijnand Mijnhardt (Universiteit Utrecht) Dr. Kasper Risbjerg Eskildsen (Roskilde Universitet, Denemarken) Contents 1. Introduction: The Transformation of the Humanities 9 What were the Humanities? 14 What was a Scholar? 24 A Map of the Learned World 31 A Scientific Revolution? 34 Enlightenment, Romanticism, and Conceptual Change 39 An Integrated Approach 47 Styles of Reasoning 48 Forms of Presentation 54 Ways of Criticism 64 Types of Intertextuality 69 2. A Science of Letters? Forms of ‘Normal Science’ in the 18th-century Humanities 79 The Ideal of Grand History and the Practice of Compilation 84 Antiquarianism and the Compendium 92 Rethinking Universal History 103 General Grammar and the ‘Science of Language’ 114 Strange Hybrids and the ‘Origin of Language’ Debate 124 The End of ‘Letters’? 136 3. -

February Njv Athens Plaza News

P L A Z A N E W S A BUCKET LIST FEBRUARY 2020 FOR YOUR STAY IN ATHENS Q U E A R L O I M T Y D T N I A M E S P I I N T A L T E H V E A N R T S T H E N J V E X P E R I E N C E P L A Z A N E W S 0 1 Relax, enjoy, recharge at The NJV Athens Plaza before & after you head to the city French inspiration G r e e k - F r e n c h C h e f H e n r i G u i b e r t c r e a t e s 2 n e w s p e c i a l m e n u s c o m b i n i n g f a v o r i t e p r o d u c t s o f t h e G r e e k l a n d , f o l l o w i n g a F r e n c h t e c h n i q u e f o r t w o d i f f e r e n t m e n u s t h a t w i l l e n r i c h t h e A t h e n i a n g a s t r o n o m i c e x p e r i e n c e . -

Networks of Modernity: Germany in the Age of the Telegraph, 1830–1880

OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 24/3/2021, SPi STUDIES IN GERMAN HISTORY Series Editors Neil Gregor (Southampton) Len Scales (Durham) Editorial Board Simon MacLean (St Andrews) Frank Rexroth (Göttingen) Ulinka Rublack (Cambridge) Joel Harrington (Vanderbilt) Yair Mintzker (Princeton) Svenja Goltermann (Zürich) Maiken Umbach (Nottingham) Paul Betts (Oxford) OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 24/3/2021, SPi OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 24/3/2021, SPi Networks of Modernity Germany in the Age of the Telegraph, 1830–1880 JEAN-MICHEL JOHNSTON 1 OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 24/3/2021, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Jean-Michel Johnston 2021 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2021 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. -

European Journal of Turkish Studies, 12 | 2011 How the North Was Won 2

European Journal of Turkish Studies Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey 12 | 2011 Demographic Engineering - Part II How the North was won Épuration ethnique, échange des populations et politique de colonisation dans la Macédoine grecque. How the North was won. Ethnic cleansing, population exchange and settlement policy in Greek Macedonia. Tassos Kostopoulos Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ejts/4437 DOI : 10.4000/ejts.4437 ISSN : 1773-0546 Éditeur EJTS Référence électronique Tassos Kostopoulos, « How the North was won », European Journal of Turkish Studies [En ligne], 12 | 2011, mis en ligne le 13 décembre 2011, consulté le 16 février 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/ejts/4437 ; DOI : 10.4000/ejts.4437 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 février 2020. © Some rights reserved / Creative Commons license How the North was won 1 How the North was won Épuration ethnique, échange des populations et politique de colonisation dans la Macédoine grecque. How the North was won. Ethnic cleansing, population exchange and settlement policy in Greek Macedonia. Tassos Kostopoulos 1 S’il est une région de la Grèce où l’ « ingénierie démographique » fut appliquée comme un élément plus ou moins constant de la politique étatique, c’est bien la Macédoine. Après l’incorporation de cette région dans le royaume grec en 1913 et jusqu’aux années 1960 au moins, des plans pour la transformation radicale de la composition ethnique de sa population se sont succédés pendant des décennies ; certains de ces projets avaient l’aval enthousiaste de la « communauté internationale » de leur temps, tandis que d’autres étaient formulés dans le secret le plus absolu ; une partie de ces plans ont été appliqués, d’autres sont restés finalement sur le papier. -

The Last Phase

The Eastern Question: THE LAST PHASE A STUDY IN GREEK-TURKISH DIPLOMACY Harry J. Psomiades Queens College and The Graduate School The City University of New York With an Introduction by Van Coufoudakis THE EASTERN QUESTION: THE LAST PHASE A STUDY IN GREEK-TURKISH DIPLOMACY The Eastern Question: The Last Phase A STUDY IN GREEK-TURKISH DIPLOMACY Harry J. Psomiades Queens College and the Graduate School The City University of New York With an Introduction by Van Coufoudakis PELLA PELLA PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC. New York, NY 10018-6401 This book was published for The Center for Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, Queens College of the City University of New York, which bears full editorial responsibility for its contents. MODERN GREEK RESEARCH SERIES, IX, SEPTEMBER 2000 THE EASTERN QUESTION: THE LAST PHASE Second Edition © Copyright 2000 The Center for Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, Queens College of the City University of New York Flushing, NY 11367-0904 All rights reserved Library of Congress Control Number 00-134738 ISBN 0-918618-79-7 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY ATHENS PRINTING COMPANY 337 West 36th Street New York, NY 10018-6401 To Kathy and Christine Acknowledgments The Eastern Question: The Last Phase has been out of print for some years, although it has survived the test of time and continues to be widely quoted by scholars dealing with the vital decade of the twenties in Greek-Turkish relations. As a result of continued demand for the book and its usefulness for understanding the present in Greek-Turkish relations, it is being presented here in a second printing, but with a new introduction by Professor Van Coufoudakis, in the Modern Greek Research Series of the Queens College Center for Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. -

Long Waves in Politics and Institutions: the Case of Greece Jason Koutoufaris-Malandrinos

Long Waves in Politics and Institutions: The case of Greece Jason Koutoufaris-Malandrinos To cite this version: Jason Koutoufaris-Malandrinos. Long Waves in Politics and Institutions: The case of Greece. 2015, http://bestimmung.blogspot.gr/2015/10/long-waves-in-politics-and-institutions.html. hal-01352167 HAL Id: hal-01352167 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01352167 Submitted on 5 Aug 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License LONG WAVES IN POLITICS AND INSTITUTIONS : THE CASE OF GREECE * by Jason Koutoufaris-Malandrinos Le grand homme dʼaction est celui qui pèse exactement lʼétroitesse de ses possibilités, qui choisit de sʼy tenir et de profiter même du poids de lʼinévitable pour lʼajouter à sa propre poussée. Fernand Braudel 1. I ntroduction It is known that Kondratieff waves reflect long-run movements in price indices and interest rates, and, by extension, fluctuations in general economic activity. Can we discern similar patterns in politics and institutional change? I will attempt a comparative sketch of the political institutions and ideologies in Greece during the periods 1821/1831 to 1910 and 1940/1949 to 2015. -

By Konstantinou, Evangelos Precipitated Primarily by the Study

by Konstantinou, Evangelos Precipitated primarily by the study of ancient Greece, a growing enthusiasm for Greece emerged in Europe from the 18th century. This enthusiasm manifested itself in literature and art in the movements referred to as classicism and neoclassicism. The founda- tions of contemporary culture were identified in the culture of Greek antiquity and there was an attempt to learn more about and even revive the latter. These efforts manifested themselves in the themes, motifs and forms employed in literature and art. How- ever, European philhellenism also had an effect in the political sphere. Numerous societies were founded to support the cause of Greek independence during the Greek War of Independence, and volunteers went to Greece to join the fight against the Ottoman Empire. Conversely, the emergence of the Enlightenment in Greece was due at least in part to the Greek students who studied at European universities and brought Enlightenment ideas with them back to Greece. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Literary and Popular Philhellenism in Europe 2. European Travellers to Greece and Their Travel Accounts 3. The Greek Enlightenment 4. Reasons for Supporting Greece 5. Philhellenic Germany 6. Lord Byron 7. European Philhellenism 8. Societies for the Support of the Greeks 9. Bavarian "State Philhellenism" 10. Jakob Philip Fallmerayer and Anti-Philhellenism 11. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Bibliography 3. Notes Indices Citation The neo-humanism of the 18th and 19th centuries contributed considerably to the emergence of a philhellenic1 climate in Europe. This new movement was founded by Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) (ᇄ Media Link #ab), who identified aesthetic ideals and ethical norms in Greek art, and whose work Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums (1764) (ᇄ Media Link #ac) (History of the Art of Antiquity) made ancient Greece the point of departure for an aestheticizing art history and cultural history. -

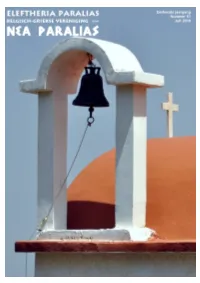

Nea Paralias 51 - Juli 2018 3

Nea Paralias . Dertiende jaargang - Nummer 51 - Juli 2018 . Lees in dit nummer ondermeer : . 3 Voorwoord De voorbeschouwingen van André, onze voorzitter . 3 Uw privacy Eleftheria Paralias en de nieuwe privacywetgeving . 4 Agenda De komende activiteiten, o.a. voordracht, uitstap, kookavond, enz… . 8 Ledennieuws In de kijker: ons muzikaal lid Carl Deseyn . 10 Terugblik Nabeschouwingen over de drie laatste activiteiten . 12 Dialecten en accenten Mopje uit Kreta, in het dialect, met een verklarende uitleg . 14 Actueel Drie maanden wel en wee in Griekenland . 26 Zeg nooit… Er zijn woorden die je maar beter niet uitspreekt . Een drankje uit Corfu, het Aristoteles-menu . 27 Culinair en 3 nieuwe recepten van Johan Vroomen . Inspiratie nodig voor een cadeautje voor je schoonmoeder? Op andere . 29 Griekse humor pagina’s: Remedie tegen kaalheid, Standbeeld . 30 Reisverslag De EP-groepsreis Kreta 2016 deel 5 . Pleinen en buurten Namen van pleinen, straten en buurten hebben meestal een . 32 achtergrond, maar zoals overal weten lokale bewoners niet waarom . van Athene die namen werden gegeven of hoe ze zijn ontstaan . Over de 5.000-drachme brug, ’s werelds oudste olijfboom, . 35 Wist je dat… en andere wetenswaardigheden . Ondermeer de Griekse deelname aan het songfestival . 36 Muziekrubriek en een Kretenzische parodie die een grote hit is . 38 Bestemmingen Reistips en bezienswaardigheden . Bouboulina, de laatste ambachtelijke bladerdeegbakker, . 40 Merkwaardige Grieken . en de Dame van Ro . 43 George George en afgeleide namen zijn de populairste namen voor mannen . 44 Unieke tradities De Botides, het jaarlijkse pottenbreken op Corfu . 44 Links Onze selectie websites die we de voorbije maanden bezochten; . eveneens links naar mooie YouTube-video’s .