The Lost Story of Iqbal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amicus Brief for Aref and Hossain

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK YASSIN AREF, Petitioner, Case No. 1:04-CR-402 (TJM) V. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. MOHAMMED MOSHARREF HOSSAIN, Petitioner, Case No. 1:04-CR-402 (TJM) V. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. Proposed AMICUS BRIEF Project SALAM, the Muslim Solidarity Committee And the Masjid As Salaam ________________________________________________________________________ On October 10, 2006, Yassin Muhidden Aref (hereinafter “Aref”), and Mohammed Mosharref Hossain (hereinafter “Hossain”) were convicted of terrorism-related charges in connection with an FBI sting involving the sale of a fake missile for a fictitious terrorist attack, and for money laundering. Aref was also convicted of one count of lying to the FBI. On March 8, 2007 the two defendants were sentenced to 15 years incarceration each. Their appeals to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and to the U.S. Supreme Court were denied, and they have exhausted their appellate remedies. Aref and Hossain have petitioned this court pursuant to the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, Section 2255 for, among other issues, the appointment of an independent prosecutor to review their cases to determine if the government and the courts provided them with necessary exculpatory information, a fair trial and justice. They seek relief similar to what was granted in People v. Theodore Stevens (a Stevens review), or what the Inspector General of the Department of Justice recommended in his June 10, 2009 Report to correct the failure of the Justice Department to identify and provide exculpatory information in terrorism cases – an independent review. Amici, Muslim Solidarity Committee (hereinafter “MSC”), Project SALAM (hereinafter “SALAM”), and the Masjid As-Salaam respectfully submit this Amicus brief, pursuant to Rule 29 in support of the defendants 2255 petition and to present information which may assist the court in deciding the issues raised by the defendants, especially where the defendants are unrepresented. -

Exhaustion and Regeneration in 9/11 Speculative Fiction: Kris Saknussemm‘S ―Beyond the Flags‖ (2015)1

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos, 22 (2018) Seville, Spain, ISSN 1133-309-X, 13-35 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/REN.2018.i22.01 EXHAUSTION AND REGENERATION IN 9/11 SPECULATIVE FICTION: KRIS SAKNUSSEMM‘S ―BEYOND THE FLAGS‖ (2015)1 SONIA BAELO-ALLUÉ Universidad de Zaragoza [email protected] Received 14 July 2018 Accepted 17 December 2018 KEYWORDS: 9/11 fiction; speculative fiction; blank fiction; trauma fiction; Kris Saknussemm; ―Beyond the Flags;‖ Douglas Lain; In the Shadow of the Towers PALABRAS CLAVE: Ficción del 11 de septiembre; ficción especulativa; blank fiction; ficción de trauma; Kris Saknussemm; ―Beyond the Flags;‖ Douglas Lain; In the Shadow of the Towers ABSTRACT Early 9/11 fiction has often been criticised for focusing too much on the victims and on the local aspects of the tragedy ignoring the global and political consequences of the attacks. 9/11 speculative fiction writers have taken longer to engage directly with the tragedy and when doing so they have also often adopted trauma-oriented approaches that could appease but not challenge. In 2015 Douglas Lain edited In the Shadow of the Towers: Speculative Fiction in a Post- 9/11 World, a collection that shows how the idiom of the fantastic can be serious and meaningful and also a means to explore cultural anxieties in the United States. Within Lain‘s collection, this paper pays special attention to Kris Saknussemm‘s ―Beyond the Flags,‖ a story that combines cultural anxieties of our time and helps readers confront their own contradictions by questioning accepted assumptions like the sacred nature of the victims or the expected 1 The research carried out for the writing of this article is part of a project financed by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) (code FFI2015-63506). -

The War on Terror As a Self-Inflicted Disaster Ian S

*ğĕĖġĖğĕĖğĥ 3065*/( 10-*$:3&1035 Our Own Strength Against Us The War on Terror as a Self-Inflicted Disaster Ian S. Lustick* April 2008 &YFDVUJWF4VNNBSZ The War on Terror is much more than a colos- serious terrorist threat cannot even be a topic of sal waste. It is the most potent threat Americans public discussion. Politicians, the news media, face to their liberties and security. With one rival government agencies, defense contractors, spectacular blow al-Qaeda managed to exploit lobbyists of all kinds, universities, and the enter- the fantasies of a “New American Century” ca- tainment industry battle ferociously to increase bal inside the Bush administration and sucker revenues and pump up reputations by posing as the American people and its leaders into a re- more committed to winning the War on Terror sponse that serves its interests. The overstated, than their competitors. Frustrated by their in- but publicly honored, “War on Terror” and the ability to find any evidence of serious terrorist catastrophic invasion of Iraq associated with it activities in the U.S., law enforcement and re- rescued the jihadi movement from oblivion by lated agencies escalate techniques of pre-emp- convincing most of the Muslim world that ji- tive prosecution and entrapment to justify their hadi propaganda about the “infidel Christians enormous budgets. and Jews” was actually correct. Terror is a problem, but the War on Terror, At home, Americans have been so bam- because it turns U.S. power against America, is boozled by the hysterical imagery of the War on a catastrophe. Terror that the absence of evidence of a truly *Ian S. -

Don Delillo and 9/11: a Question of Response

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 5-2010 Don DeLillo and 9/11: A Question of Response Michael Jamieson University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Jamieson, Michael, "Don DeLillo and 9/11: A Question of Response" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 28. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DON DELILLO AND 9/11: A QUESTION OF RESPONSE by Michael A. Jamieson A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Marco Abel Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 DON DELILLO AND 9/11: A QUESTION OF RESPONSE Michael Jamieson, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2010 Advisor: Marco Abel In the wake of the attacks of September 11th, many artists struggled with how to respond to the horror. In literature, Don DeLillo was one of the first authors to pose a significant, fictionalized investigation of the day. In this thesis, Michael Jamieson argues that DeLillo’s post-9/11 work constitutes a new form of response to the tragedy. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Witness to Abuse Human Rights Abuses Under the Material Witness Law Since September 11

Human Rights Watch June 2005 Vol. 17, No. 2 (G) Witness to Abuse Human Rights Abuses under the Material Witness Law since September 11 Summary......................................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations......................................................................................................................... 7 To the Justice Department ...................................................................................................... 7 To Congress............................................................................................................................... 8 To the Judiciary......................................................................................................................... 9 I. The Material Witness Law: Overview and Pre-September 11 Use.................................. 10 Overview of the Material Witness Law ............................................................................... 12 Arrest of Material Witnesses before September 11 ........................................................... 14 II. Post-September 11 Material Witness Detention Policy................................................... 15 III. Misuse of the Material Witness Law to Hold Suspects as Witnesses........................... 17 Suspects Held as Witnesses................................................................................................... 20 Prolonged Incarceration and Undue Delays in Presenting Witnesses -

Hitler's Doubles

Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos Fully-Illustrated Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles: Fully-Illustrated By Peter Fotis Kapnistos [email protected] FOT K KAPNISTOS, ICARIAN SEA, GR, 83300 Copyright © April, 2015 – Cold War II Revision (Trump–Putin Summit) © August, 2018 Athens, Greece ISBN: 1496071468 ISBN-13: 978-1496071460 ii Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos © 2015 - 2018 This is dedicated to the remote exploration initiatives of the Stargate Project from the 1970s up until now, and to my family and friends who endured hard times to help make this book available. All images and items are copyright by their respective copyright owners and are displayed only for historical, analytical, scholarship, or review purposes. Any use by this report is done so in good faith and with respect to the “Fair Use” doctrine of U.S. Copyright law. The research, opinions, and views expressed herein are the personal viewpoints of the original writers. Portions and brief quotes of this book may be reproduced in connection with reviews and for personal, educational and public non-commercial use, but you must attribute the work to the source. You are not allowed to put self-printed copies of this document up for sale. Copyright © 2015 - 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Hitler’s Doubles The Cold War II Revision : Trump–Putin Summit [2018] is a reworked and updated account of the original 2015 “Hitler’s Doubles” with an improved Index. Ascertaining that Hitler made use of political decoys, the chronological order of this book shows how a Shadow Government of crisis actors and fake outcomes operated through the years following Hitler’s death –– until our time, together with pop culture memes such as “Wunderwaffe” climate change weapons, Brexit Britain, and Trump’s America. -

Scare Tactics: Ashcroft's Phony 'War on Terrorism'

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 31, Number 12, March 26, 2004 EIRNational Scare Tactics: Ashcroft’s Phony ‘War on Terrorism’ by Edward Spannaus Once described as America’s “de facto Minister of Fear,” Convictions Without Trials Attorney General John Ashcroft fit that description in a state- The fraud of Ashcroft’s “war on terrorism” was dramati- ment issued on March 4, immediately after the conviction cally demonstrated in December, when a research institute of three defendants in the “Virginia Jihad” case. Ashcroft associated with Syracuse University, the Transactional Re- declared: “Today, Americans get a glimpse of what is hiding cords Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), published a study in the shadows. Terrorists recruit, train, and finance jihad which blew a major hole in Ashcroft’s scare campaign about in America.” “Islamic terrorists” and “sleeper cells” inside the United The truth is that Ashcroft’s “war on terrorism” gives no States. The study showed that there had been a sharp increase such glimpse; it is a gigantic dud. The blunderbus tools given in the number of convictions in serious terrorism cases in the by Congress to the Justice Department have enabled Ashcroft two years following the 9/11 attacks, from 96 for the two and Co. to use the threat of draconian prison sentences to years prior to September 2001, to 341 for the two years after. force defendants to plead guilty to offenses that they may or What was most surprising about the Syracuse study was what may have not committed. As a result, the Justice Department it showed about sentences. -

In Pursuit of Justice Prosecuting Terrorism Cases in the Federal Courts 2009 Update and RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

In Pursuit of Justice Prosecuting Terrorism Cases in the Federal Courts 2009 UPDATE AND RECENT DEVELOPMENTS Richard B. Zabel James J. Benjamin, Jr. July 2009 About Us Human Rights First believes that building respect for human rights and the rule of law will help ensure the dignity to which every individual is entitled and will stem tyranny, extremism, intolerance, and violence. Human Rights First protects people at risk: refugees who flee persecution, victims of crimes against humanity or other mass human rights violations, victims of discrimination, those whose rights are eroded in the name of national security, and human rights advocates who are targeted for defending the rights of others. These groups are often the first victims of societal instability and breakdown; their treatment is a harbinger of wider-scale repression. Human Rights First works to prevent violations against these groups and to seek justice and accountability for violations against them. Human Rights First is practical and effective. We advocate for change at the highest levels of national and international policymaking. We seek justice through the courts. We raise awareness and understanding through the media. We build coalitions among those with divergent views. And we mobilize people to act. Human Rights First is a non-profit, nonpartisan international human rights organization based in New York and Washington D.C. To maintain our independence, we accept no government funding. This report is available for free online at www.humanrightsfirst.org © 2009 Human Rights First. All Rights Reserved. Headquarters Washington D.C. Office 333 Seventh Avenue 100 Maryland Avenue, NE 13th Floor Suite 500 New York, NY 10001-5108 Washington, DC 20002- 5625 Tel.: 212.845.5200 Tel: 202.547.5692 Fax: 212.845.5299 Fax: 202.543.5999 www.humanrightsfirst.org In Pursuit of Justice: 2009 Update Preface As the Obama Administration takes steps to shut down analyzed 119 cases with 289 defendants. -

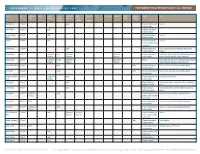

Terrorist Trial Report Card: U.S. Edition – Appendix B

SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 – SEPTEMBER 11, 2006 TERRORIST TRIAL REPORT CARD: U.S. EDITION Name Date Commercial Drugs General General Immigration National Obstruction Other Racketeering Terrorism Violent Weapons Sentence Notes Fraud Fraud Criminal Violations Security of Crimes Violations Conspiracy Violations Investigation Khalid Al Draibi 12-Sep-01 Guilty 4 months imprisonment, 36 Deported months probation Sherif Khamis 13-Sep-01 Guilty 2.5 months imprisonment, 36 months probation Jean-Tony Antoine 14-Sep-01 Guilty 12 months imprisonment, Deported Oulai 24 months probation Atif Raza 17-Sep-01 Guilty 4.7 months imprisonment, Deported 36 months probation, $4,183 fine/restitution Francis Guagni 17-Sep-01 Guilty 20 months imprisonment, French national arrested at Canadian border with box cutter; 36 months probation Deported Ahmed Hannan 18-Sep-01 Acquitted or Guilty Acquitted or Acquitted or 6 months imprisonment, 24 Detroit Sleeper Cell Case (Karim Koubriti, Ahmed Hannan, Youssef Dismissed Dismissed Dismissed months probation Hmimssa, Abdel Ilah Elmardoudi, Farouk Ali-Haimoud) Karim Koubriti 18-Sep-01 Acquitted or Pending Acquitted or Acquitted or Pending Detroit Sleeper Cell Case (Karim Koubriti, Ahmed Hannan, Youssef Dismissed Dismissed Dismissed Hmimssa, Abdel Ilah Elmardoudi, Farouk Ali-Haimoud) Vincente Rafael Pierre 18-Sep-01 Guilty Guilty 24 months imprisonment, Pierre et al. (Vincente Rafael Pierre, Traci Elaine Upshur) 36 months probation Traci Upshur 18-Sep-01 Guilty Guilty 15 months imprisonment, 24 Pierre et al. (Vincente Rafael Pierre, -

Torturing Alberto Jan 20Th 2005 | WASHINGTON, DC from the Economist Print Edition

Economist.com Page 1 of 3 About sponsorship The domestic war on terror Torturing Alberto Jan 20th 2005 | WASHINGTON, DC From The Economist print edition A mixed inheritance for America's next attorney-general AP Long time no see THE war on terror, Alberto Gonzales told members of the Senate on January 6th, would be his top priority as America's next attorney-general. How effective has the Justice Department been under John Ashcroft in fighting terrorism at home? To conservatives and the department itself, this is an easy question to answer. No act of terrorism has occurred on American soil since the attacks on September 11th 2001. Polls show Americans feeling ever safer. According to the department's own tally, it has charged 375 people with crimes in “terrorism-related” investigations since September 11th—and 195 have been convicted or pleaded guilty. Yet critics insist that the department is overcounting; and that it has overreached its powers. Few people dispute the Justice Department's decision after September 11th to shift its focus away from prosecuting terrorists after the fact to breaking up terror plots in advance. To this end, it has marshalled an arsenal of legal weapons to put terrorists behind bars. So far most controversy has http://www.economist.com/PrinterFriendly.cfm?Story_ID=3577485 2/4/2005 Economist.com Page 2 of 3 centred on Mr Ashcroft's tour de force, the USA Patriot Act, which was rushed through Congress after the attacks. This dissolved the wall between the intelligence and criminal arms of an investigation. It also boosted the government's powers of surveillance sufficiently to provoke protests from civil-liberties groups about “sneak-and-peek searches” (though America is still less intrusive than many governments in Europe). -

The Terrorist Sleeper Threat in an Age of Anxiety About the Author

DSFG/WIIS-C Working Paper April 2021 Author Dr. Shannon Nash The Terrorist Sleeper Threat in an Age of Anxiety About the Author Dr. Shannon Nash is the Postdoctoral Network Manager of the North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network (NAADSN). She coordinates NAADSN events, re- search projects and outputs, multimedia presence, website, and reports. She promotes relationships between the network and collaborators and manages NAADSN’s student and graduate research fellows. As part of her work with NAADSN, Dr. Nash is a post-doctoral r esearch fellow at Trent University studying past and present terrorist threats and attacks as well as Canadian, American, and international defence, security and counterterrorism policies. Her current research examines the fluidity of the “terrorism” label and how the label is informed and applied to a violent attack in Canada. This research looks at how racism, Islamophobia and white supremacy, and how and who we frame as “other”, or “terrorist”, are all profoundly connected. Dr. Nash is also working on a project at the University of Water- loo that looks at education and training in national security and counterterrorism in Cana- da. She has recently completed a review of important studies and practical efforts to anticipate and reduce risk factors contributing to lasting traumatization of terrorist victims for a chapter in the forthcoming Handbook of Terrorism Prevention and Preparedness (Ed. Alex P. Schmid). Dr. Nash received her Ph.D. in History from the University of Toronto with a focus on 20th Cen- tury American History, Terrorism, and International Relations. Her doctoral thesis looks at the reality of al Qaeda espionage methodology and how the idea of a sleeper agent was per- ceived and adapted to fit the terrorist threat posed by al Qaeda from the 1990s onwards.