Chapter 3 (.Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again?

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again? INTRODUCrION "Baseball is everybody's business."' We have just witnessed the conclusion of perhaps the greatest baseball season in the history of the game. Not one, but two men broke the "unbreakable" record of sixty-one home-runs set by New York Yankee great Roger Maris in 1961;2 four men hit over fifty home-runs, a number that had only been surpassed fifteen times in the past fifty-six years,3 while thirty-three players hit over thirty home runs;4 Barry Bonds became the only player to record 400 home-runs and 400 stolen bases in a career;5 and Alex Rodriguez, a twenty-three-year-old shortstop, joined Bonds and Jose Canseco as one of only three men to have recorded forty home-runs and forty stolen bases in a 6 single season. This was not only an offensive explosion either. A twenty- year-old struck out twenty batters in a game, the record for a nine inning 7 game; a perfect game was pitched;' and Roger Clemens of the Toronto Blue Jays won his unprecedented fifth Cy Young award.9 Also, the Yankees won 1. Flood v. Kuhn, 309 F. Supp. 793, 797 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). 2. Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs and Sammy Sosa hit 66. Frederick C. Klein, There Was More to the Baseball Season Than McGwire, WALL ST. J., Oct. 2, 1998, at W8. 3. McGwire, Sosa, Ken Griffey Jr., and Greg Vaughn did this for the St. -

The Brooklyn Nine DISCUSSION GUIDE

The Brooklyn Nine DISCUSSION GUIDE “A wonderful baseball book that is more than the sum of its parts.” The Horn Book About the Book 1845: Felix Schneider cheers the New York 1945: Kat Flint becomes a star in the All- Knickerbockers as they play Three-Out, All-Out. American Girls Baseball League. 1864: Union soldier Louis Schneider plays 1957: Ten-year-old Jimmy Flint deals with bullies, baseball between battles in the Civil War. Sputnik, and the Dodgers leaving Brooklyn. 1893: Arnold Schneider meets his hero King 1981: Michael Flint pitches a perfect game in a Kelly, one of professional baseball's first big stars. Little League game at Prospect Park. 1908: Walter Snider sneaks a black pitcher into 2002: Snider Flint researches a bat that belonged the Majors by pretending he's Native American. to one of Brooklyn's greatest baseball players. 1926: Numbers wiz Frankie Snider cons a con One family, nine generations. with the help of a fellow Brooklyn Robins fan. One city, nine innings of baseball. Make a Timeline Questions for Discussion Create a timeline with pictures of First Inning: Play Ball important events from baseball and American history that Who was the first of your ancestors to come to America? correspond to the eras in each of Where is your family from? Could you have left your home to the nine innings in The Brooklyn make a new life in a foreign land? Nine. Use these dates, and add some from your own research. How is baseball different today from the way it was played by Felix and the New York Knickerbockers in 1845? First Inning: 1845 Felix's dreams are derailed by the injury he suffers during the 1835 – First Great Fire in Great Fire of 1845, but he resolves to succeed anyway. -

From the Bullpen

1 FROM THE BULLPEN Official Publication of The Hot Stove League Eastern Nebraska Division 1992 Season Edition No. 11 September 22, 1992 Fellow Owners (sans Possum): We have been to the mountaintop, and we have seen the other side. And on the other side was -- Cooperstown. That's right, we thought we had died and gone to heaven. On our recent visit to this sleepy little hamlet in upstate New York, B.T., U-belly and I found a little slice of heaven at the Baseball Hall of Fame. It was everything we expected, and more. I have touched the plaque of the one they called the Iron Horse, and I have been made whole. The hallowed halls of Cooperstown provided spine-tingling memories of baseball's days of yore. The halls fairly echoed with voices and sounds from yesteryear: "Say it ain't so, Joe." "Can't anybody here play this game?" "Play ball!" "I love Brian Piccolo." (Oops, wrong museum.) "I am the greatest of all time." (U-belly's favorite.) "I should make more money than the president, I had a better year." "Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio?" And of course: "I feel like the luckiest man alive." Hang on while I regain my composure. Sniff. Snort. Thanks. I'm much better From the Bullpen Edition No. 11 September 22, 1992 Page 2 now. If you ever get the chance to go to Cooperstown, take it. But give your wife your credit card and leave her at Macy's in New York City. She won't get it. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Em Reading: Hit a Home Run with Reading

Hit a Home Run with Reading! • Keep ’em Reading • Grades by | Carol Thompson K–2, 3–5 Library Incentive Program and Party Join the World Series anticipation with this read- ing incentive and encourage your students to hit a home run. This month-long unit will prove to a fun learning experience. Objective: To get kids to read Incentive Summary This is a great incentive for October (World Series) or springtime incentive. Using the theme of base- ball, students are encouraged to hit a home run Activities and celebrate their favorite teams and players while • Read various baseball books. (Suggested learning about the history of America’s best-loved Resources on page 4.) sport. Readers keep up with their stats on a base- • Locate fan Web sites and have students write ball field record sheet and earn tickets to the com- a letter to a favorite player, manager, or coach. munity minor league baseball team on the school Teach and/or review proper form for friendly night. The school also hosts an old-fashioned hot letter. Letters can be e-mailed too. dog and apple pie cookout. • Act out the book Casey at the Bat or use it as a reader’s theater. • Have a favorite team dress-up day where stu- Bulletin Board dents wear their baseball/softball uniforms Here’s a sample of our “Hit a Home Run with (including hats which are normally against Reading!” bulletin board. Get creative. Baseball dress code so the kids love it!). bats and baseballs can create great letters. It also • Have the High School baseball or softball team looks good to use old book covers on this bulletin players or coaches come and read to classes board for a 3-D effect. -

Baseball Cards

Durham and the Rise of the Baseball Card Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………….2 How to Use this Educator’s Guide………………………3 Exhibit Outline & Explorations……………………………5 Key Exhibit Themes……………………………………………7 Themed Activities………………………………………………8 Key Exhibit Terms…………………………………………….17 Museum of Durham History | History Hub………18 Curriculum Standards………………………………………19 1 Introduction The baseball card. It’s one of America’s most timeless novelties. Today, you might find one in a sporting goods store, in an auction house or even on your smartphone. However, the baseball card wasn’t always a fun collector’s item. In fact, it began as a creative advertising tool for businessmen. The baseball card came about at a time of major change in America. This exhibit examines that change, and demonstrates how the card evolved as social issues shaped communities like Durham. The exhibit will allow students to explore how different historical eras shaped baseball card advertising, and the sport as a whole. Students will also have the opportunity to understand Durham’s role in baseball card advertising. The exhibit draws together five major themes, including: • Technology & Industry • Advertising • Race & Culture • Community Contributions • Leisure in America 2 How to Use this Educator’s Guide This Educator’s Guide will help educators and students draw connections between the historical content in “Durham and the Rise of the Baseball Card” and classroom topics. Prior to engaging with the exhibit, educators should review the exhibit outline, which gives an in-depth overview of the chronology and subject matter of the exhibit. The exhibit outline may also aid you in preparing lesson plans and classroom activities that relate directly to historical subject matter addressed in the exhibit. -

Baseball Autographs Signed 1950-55 Callahans 297 Honus Wagner 9

January 31 Auction: Baseball Autographs Signed 1950-55 Callahans 297 Honus Wagner 9 ............................ 500 Such a neat item, offered is a true high grade hand-signed 290 Fred Clarke 9.5 ......................... 100 Honus Wagner baseball card. So hard to find, we hardly ever Sharp card, this looks to be a fine Near Mint. Signed in par- see any kind of card signed by the legendary and beloved ticularly bold blue ink, this is a terrific autograph. Desirable Wagner. The offered card, slabbed by PSA/DNA, is well signed card, deadball era HOFer Fred Clarke died in 1960. centered with four sharp corners. Signed right in the center PSA/DNA slabbed. in blue fountain pen, this is a very nice signature. Key piece, this is another item that might appreciate rapidly in the 291 Clark Griffith 9 ............................ 150 future given current market conditions. Very scarce signed card, Clark Griffith died in 1955, giving him only a fairly short window to sign one of these. Sharp 298 Ed Walsh 9 ............................ 100 card is well centered and Near Mint or better to our eyes, Desirable signed card, this White Sox HOF pitcher from the this has a fine and clean blue ballpoint ink signature on the deadball era died in 1959. Signed neatly in blue ballpoint left side. PSA/DNA slabbed. ink in a good spot, this is a very nice signature. Slabbed Authentic by PSA/DNA, this is a quality signed card. 292 Rogers Hornsby 9.5 ......................... 300 Remarkable signed card, the card itself is Near Mint and 299 Lot of 3 w/Sisler 9 ..............................70 quite sharp, the autograph is almost stunningly nice. -

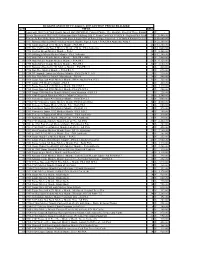

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Chapter 2 (.Pdf)

Players' League-Chapter 2 7/19/2001 12:12 PM "A Structure To Last Forever":The Players' League And The Brotherhood War of 1890" © 1995,1998, 2001 Ethan Lewis.. All Rights Reserved. Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 "If They Could Only Get Over The Idea That They Owned Us"12 A look at sports pages during the past year reveals that the seemingly endless argument between the owners of major league baseball teams and their players is once more taking attention away from the game on the field. At the heart of the trouble between players and management is the fact that baseball, by fiat of antitrust exemption, is a http://www.empire.net/~lewisec/Players_League_web2.html Page 1 of 7 Players' League-Chapter 2 7/19/2001 12:12 PM monopolistic, monopsonistic cartel, whose leaders want to operate in the style of Gilded Age magnates.13 This desire is easily understood, when one considers that the business of major league baseball assumed its current structure in the 1880's--the heart of the robber baron era. Professional baseball as we know it today began with the formation of the National League of Professional Baseball Clubs in 1876. The National League (NL) was a departure from the professional organization which had existed previously: the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players. The main difference between the leagues can be discerned by their full titles; where the National Association considered itself to be by and for the players, the NL was a league of ball club owners, to whom the players were only employees. -

Probable Starting Pitchers 31-31, Home 15-16, Road 16-15

NOTES Great American Ball Park • 100 Joe Nuxhall Way • Cincinnati, OH 45202 • @Reds • @RedsPR • @RedlegsJapan • reds.com 31-31, HOME 15-16, ROAD 16-15 PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS Sunday, June 13, 2021 Sun vs Col: RHP Tony Santillan (ML debut) vs RHP Antonio Senzatela (2-6, 4.62) 700 wlw, bsoh, 1:10et Mon at Mil: RHP Vladimir Gutierrez (2-1, 2.65) vs LHP Eric Lauer (1-2, 4.82) 700 wlw, bsoh, 8:10et Great American Ball Park Tue at Mil: RHP Luis Castillo (2-9, 6.47) vs LHP Brett Anderson (2-4, 4.99) 700 wlw, bsoh, 8:10et Wed at Mil: RHP Tyler Mahle (6-2, 3.56) vs RHP Freddy Peralta (6-1, 2.25) 700 wlw, bsoh, 2:10et • • • • • • • • • • Thu at SD: LHP Wade Miley (6-4, 2.92) vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, 10:10et CINCINNATI REDS (31-31) vs Fri at SD: RHP Tony Santillan vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, 10:10et Sat at SD: RHP Vladimir Gutierrez vs TBD 700 wlw, FOX, 7:15et COLORADO ROCKIES (25-40) Sun at SD: RHP Luis Castillo vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, mlbn, 4:10et TODAY'S GAME: Is Game 3 (2-0) of a 3-game series vs Shelby Cravens' ALL-TIME HITS, REDS CAREER REGULAR SEASON RECORD VS ROCKIES Rockies and Game 6 (3-2) of a 6-game homestand that included a 2-1 1. Pete Rose ..................................... 3,358 All-Time Since 1993: ....................................... 105-108 series loss to the Brewers...tomorrow night at American Family Field, 2. Barry Larkin ................................... 2,340 At Riverfront/Cinergy Field: ................................. -

Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis

Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Before They Were Cardinals SportsandAmerican CultureSeries BruceClayton,Editor Before They Were Cardinals Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Columbia and London Copyright © 2002 by The Curators of the University of Missouri University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201 Printed and bound in the United States of America All rights reserved 54321 0605040302 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cash, Jon David. Before they were cardinals : major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. p. cm.—(Sports and American culture series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8262-1401-0 (alk. paper) 1. Baseball—Missouri—Saint Louis—History—19th century. I. Title: Major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. II. Title. III. Series. GV863.M82 S253 2002 796.357'09778'669034—dc21 2002024568 ⅜ϱ ™ This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984. Designer: Jennifer Cropp Typesetter: Bookcomp, Inc. Printer and binder: Thomson-Shore, Inc. Typeface: Adobe Caslon This book is dedicated to my family and friends who helped to make it a reality This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix Prologue: Fall Festival xi Introduction: Take Me Out to the Nineteenth-Century Ball Game 1 Part I The Rise and Fall of Major League Baseball in St. Louis, 1875–1877 1. St. Louis versus Chicago 9 2. “Champions of the West” 26 3. The Collapse of the Original Brown Stockings 38 Part II The Resurrection of Major League Baseball in St. -

Sailor I 29 .370 Fore This Year

s s s rrrr#M*«*M^ ■ ++++*++++++++++++++»* r rt rrstrrrr *r**rr*+s •*»***■* r rest rtrt* r i rrt *®H m® TXe BROWNSVILLE HERALD SPORTS SECTION 4 '*>» ------------------> »»»«»«««< w«*i i Pirates Continue BUNION DERBY Carpentier Declares HIT OR SIT’ Dallas Increases Winning Streak at DEVELOPS DUEL Schmeling Wide Open IT USED TO BE Lead In Texas To LAKEWOOD. N. J.. June 13.— maul three sparring partners Amos Rusie Old Time of Giants Salo Cuts Down Says Three Full Games Gavuzzi’s around the Expense • hP—Georges Carpentier. lean as ring. The orchid man beamed on the Hurlers Not Afraid of Lead; Race Is Near- on that July day in 1921 when a correspondents. Heavy Sluggers By GAYLE TALBOT. JK. By WILLIAM J. CH1PMAN ing Finish heavyweight crown trembled for “I can't tell who I think you Associated Pm* Sports Writer Associated Press Sports Writer a moment under the crash of his will win the bout between SEATTLE. June 13.—(AH— Amos race the Texas league has seen since it was In 1U Claad The Pirate charge remains unchecked, even with the Giants opposing fists, stood outside a ring look- Schmeling and Paulino Uzcud- The greatest Rusie, original king of the strikeout the word of President J Doak Roberta— ft. John J. McGraw was forced to chafe in the New York dugout at JACUMBA, Cal., June 13.—L>P>— ing in. un—at least not he C swaddling clothes—taking here.” said. cannot understand With less than 20 minutes He stared at a • pitchers, why a little as the stampeding Dallas Steers opened m Forbes Field yesterday as the Pirates gave his charges a one-run defeat separat- husky youth in many ways this Schmeling streched cut yesterday the two leaders in modem hurlers don't pitch t6 the the Mavericks in the ninth after The ing the Pyle cross the knowing speak of careless*;, does look like series at Waco with their fourth straight victory.