Understanding Lutherans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kircbltcbca DER

Kircbltcbca DER II. Band Ausgeg~ben am 1.April 1970 Nr. 3/1970 I. Staatsgesetze Ill. Bekanntmachungen 11.· KircQengesetze und Verordnungen IV. Kirchliche Organe Kirchengesetz zu dem Vertrag uber die Bildung der Synode Nordelbischen evangelisch.:.Iutherischen Kirche Missionsbeirat Vertrag über die Bildung der Nordelbischen evangelisch lutherischen Kirche Mitarbeitervertretung Grundsätze und Leitsätze für die Verfassung der V. Personalnachrichten Nordelbischen evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche - Anlage zu § 5 Absatz 2 des Vertrages - VI. Mitteilungen 1. Staat~gesetze lt Kirchengesetze und Verordnungen Kirchengesetz VERTRAG zu dem Vertrag über die Bildung über die Bildung der der Nordelbischen evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche N ordelbischen evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche Vom 18. März 1970 Die Evangelisch-lutherische Landeskirche Eutin Kirchenleitung und Synode haben gemäß Artikel 68 Ab (Landeskirche Eutin) satz 1 und Artikel 94 Absatz 1 und 2 der Kirchenverfassung - vertreten durch ~ie Kirchenleitung -, · als verfassungsänderndes Kirchengesetz beschlossen: die Evangelisch-lutherische Kirche im Hamburgischen Staate Artikel 1 (Landeskirche Hamburg) (1) Dem zwischen - vertreten durch den Kirchenrat -, . der Evangelisch-lutherischen Landeskirche Eutin, der Evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche im Hamburgischen die Evangelisch-lutherische Landeskirche Hannover~ Staate, (Landeskirche Hannover) · der Evangelisch-lutherischen Larideskirche Hannovers, - vertreten durch den Landesbischof -. der Evangelisch-lutheris·chen Kirche in Lübeck und die Evangelisch-lutherische -

“Liberated by God's Grace”

“LIBERATED BY GOD’S GRACE” Assembly Report LWF Twelfth Assembly, Windhoek, Namibia, 10–16 May 2017 “Liberated by God’s Grace” Assembly Report ASSEMBLY REPORT © The Lutheran World Federation, 2017 Published by The Lutheran World Federation – A Communion of Churches Route de Ferney 150 P. O. Box 2100 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland Design: Edwin Hassink/Brandious Concept, editing, translation, revision, layout and photo research: LWF Office for Communication Services, Department for Theology and Public Witness and Department for Planning and Operations ISBN 978-2-940459-74-2 2 LWF Twelfth Assembly Contents Foreword ...........................................................................................................................4 Address of the President .....................................................................................................6 Report of the General Secretary ........................................................................................20 Report of the Chairperson of the Finance Committee ..........................................................38 Liberated by God’s Grace – Keynote Address .....................................................................48 Message ..........................................................................................................................56 Public Statements and Resolutions ...................................................................................64 Salvation—Not for Sale .....................................................................................................86 -

Stabilisation of Movable Feasts

[Communicated to the Council and the Members of the League.] Official N o.: C. 335. M. 154. 1934. VIII. Geneva. August 3rd, 1934. LEAGUE OF NATIONS ORGANISATION FOR COMMUNICATIONS AND TRANSIT STABILISATION OF MOVABLE FEASTS SUMMARY OF REPLIES FROM RELIGIOUS AUTHORITIES TO THE LETTER FROM THE SECRETARY-GENERAL OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS COMMUNICATING THE ACT REGARDING THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL ASPECTS OF FIXING MOVABLE FEASTS I. — COMMUNICATION OF THE ACT TO THE RELIGIOUS AUTHORITIES. According to the instructions of the Council, the Secretary-General brought the Act regarding the economic and social aspects of fixing movable feasts, adopted by the Fourth General Conference on Communications and Transit, to the notice of the Christian Religious Authorities, asking them to consider as favourably as possible what action they could “take in the matter. As far as the Holy See is concerned, the Act was communicated by letter from the Secretary-General of the League to the Secretary of State of His Holiness on November 16th, As regards Christian Churches other than the Roman Catholic Church, a request was addressed on November 16th, 1932, to the President of the Universal Christian Council for Life and Work, to which all these Churches are affiliated, asking him to bring the above-mentioned Act to their knowledge and to inform the Secretary-General of the League of the views expressed by the Churches in the matter. II. — RESULTS OF THE ENQUIRY. 1. — Attitude of the Holy See. By letter dated December 30th, 1932, Cardinal Pacelli informed the Secretary-General that the Holy bee maintains the point of view already expressed in previous communications — i.e., that the stabilisation of Easter is a pre-eminently religious question which falls within the competence of the Holy See and that, for reasons of higher spiritual concern, the Holy ?>ee cannot contemplate a change in this matter. -

Moves Towards Authentic Freedom. Church and State in Switzerland, and Beyond

Moves towards Authentic Freedom. Church and State in Switzerland, and Beyond Hans Feichtinger Abstract: Many of the Swiss Cantons have regulated the relations between church and state by establishing, in their public law, corporations at the levels of the municipality and of the canton. The role and the rights of these corporations, especially obligatory membership in them, is the object of ongoing political and legal debate. Both on the side of the courts and of the church, the present system has come under scrutiny, while the corporation representatives and also a majority of the population seem intent on maintaining it. This paper explains and examines the presently valid church-state relations, focusing on the Canton of Zurich, and looks at the suggestions for reform elaborated by an experts’ commission instituted by the Conference of Swiss Bishops. In conclusion, it presents some more general reflections on the challenges to individual and corporative religious freedom today, in Switzerland and beyond. 1. Introduction If you were to ask someone how the relations between church and state are regulated in Switzerland, you would very likely obtain the classically Swiss answer: they are different in every canton and very complicated. This answer is kind of cliché, but no lie—though many might interpret it as another attempt not to reveal the state of financial affairs in the church. For understanding the history and the present situation of Swiss church-state relationships, we have to remember that European states up until fairly recently were confessional. In Switzerland, the Sonderbundskrieg, where the frontlines followed confessional divisions, occurred as late as 1847. -

10A-Assembly Report-2003-En-Low

For the Healing of the World Official Report The Lutheran World Federation Tenth Assembly Winnipeg, Canada, 21–31 July 2003 Parallel edition in German, French and Spanish: Zur Heilung der Welt – Offizieller Bericht Pour guérir le monde – Rapport officiel Para la Sanación del Mundo – Informe Official Published by The Lutheran World Federation Office for Communication Services P.O Box 2100 CH-1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland Editing, translation, revision, cover design and layout by LWF staff. Other translation, revision by Elaine Griffiths, Dagmar Otzinger, Margaret Pater Logo design by Erik Norbraten Additional copies available at cost from and Richard Nostbakken, Canada. The Lutheran World Federation All photos © LWF/D. Zimmermann Office for Communication Services unless otherwise indicated P.O Box 2100 CH-1211 Geneva 2 © 2004 The Lutheran World Federation Switzerland Printed by SRO-Kundig, Geneva e-mail [email protected] phone +41 22 791 6370 ISBN 3-905676-34-6 Official Report LWF Tenth Assembly Winnipeg, Canada, 21–31 July 2003 For the Healing of the World 2 The Lutheran World Federation Contents Foreword .........................................................................................7 The LWF from Hong Kong to Winnipeg........................................ 11 Address of the President ............................................................................... 11 Address of the General Secretary ................................................................ 25 Report of the Treasurer ............................................................................... -

Investor Expectations on Climate Change for Airlines and Aerospace Companies

Last Updated: 9 September 2020 INVESTOR EXPECTATIONS ON CLIMATE CHANGE FOR AIRLINES AND AEROSPACE COMPANIES February 2020 As long-term investors, we recognize the threat of climate change to our investments and view fulfillment of the Paris Agreement’s goal to hold global average temperature rise to “well below 2°C above preindustrial levels” as an imperative. Aviation is a carbon-intensive mode of transportation and is projected to grow rapidly in the 21st century. While this presents opportunities for aviation investors and companies, the accompanying increase in greenhouse emissions also heightens climate change-related risks.1 These include: ● Transition Risks: o Regulatory: Although current company, government, and voluntary industry- wide emissions targets are welcome,2 they will not align the sector with the net-zero world envisioned by the Paris Agreement.3 As a result, governments are likely to impose stronger emissions reduction measures on airlines and aerospace companies as the gap between the level of action needed to keep global warming to safe levels becomes more apparent.4 o Reputational: Airlines and aerospace companies may face a backlash from their consumers, investors, or other stakeholders if they, or the organizations they support, are perceived to be making insufficient efforts to reduce their emissions. The recent growth of the no-fly movements in Europe demonstrate that this is a risk that aviation companies are already confronting.5 o Legal: Airlines and aerospace companies could face growing legal risks as legal notions of company responsibility for climate change evolve. As just one example, some oil and gas majors have already faced lawsuits alleging that they misled investors and the public on climate change, despite knowing the risks.6 ● Physical risks: Airline and aerospace companies that are unprepared for the projected physical impacts of climate change—including everything from airport flooding to increases in clear-air turbulence7—could face severe consequences to assets, service and overall viability. -

Hex Signs Sacred and Celestial Symbolism in Pennsylvania Dutch Barn Stars

Hex Signs Sacred and Celestial Symbolism in Pennsylvania Dutch Barn Stars A Collaborative Exhibition Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University March 1 - November 3, 2019 A Collaborative Exhibition Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University March 1 - November 3, 2019 Hex Signs: Sacred and Celestial Symbolism in Pennsylvania Dutch Barn Stars is a collaborative effort between Glencairn Museum and the Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University. Glencairn invites a diverse audience to engage with religious beliefs and practices, past and present, with the goal of fostering empathy and building understanding among people of all beliefs. The exhibition features items from the Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University, the Schwenkfelder Library & Heritage Center, Special Collections at the Martin Library of Franklin and Marshall College, the Pennsylvania Folklife Society at the Myrin Library of Ursinus College, as well as the private collections of Eric Claypoole, Patrick J. Donmoyer, and the relatives of barn star artist Milton Hill, especially Harold & Esther (Hill) Derr, Lee Heffner, and Bart Hill. This exhibition catalog is dedicated with gratitude to the memory of barn star artist Milton J. Hill (1887-1972) of Virginville, Berks County, Pennsylvania, and to his wife Gertrude (Strasser) Hill, who supported his work, as well as to his family, especially his daughter Esther (Hill) Derr and her husband Harold Derr; his nephew Bart Hill; his grandson Lee Heffner; his granddaughter Dorian (Derr) Featheroff, and all of his descendants living and departed. A true artist of the stars, Milton Hill’s commitment to the celestial orientation of this unique Pennsylvania art form preserved and continued the folk culture’s traditional views for generations to come. -

Give Us Today Our Daily Bread Official Report

LWF EleVENTH ASSEMBLY Stuttgart, Germany, 20–27 July 2010 Give Us Today Our Daily Bread Official Report The Lutheran World Federation – A Communion of Churches Give Us Today Our Daily Bread Official Report THE LUTHERAN WORLD FEDERATION – A COMMUNION OF CHURCHES Published by The Lutheran World Federation Office for Communication Services P.O. Box 2100 CH-1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.lutheranworld.org Parallel editions in German, French and Spanish Unser tägliches Brot gib uns heute! – Offizieller Bericht Donne-nous aujourd’hui notre pain quotidien – Rapport officiel Danos Hoy Nuestro Pan de Cada Día – Informe Oficial Editing, translation, revision, cover design and layout by LWF Office for Communication Services Other translation, revision by Elaine Griffiths, Miriam Reidy-Prost and Elizabeth Visinand Logo design by Leonhardt & Kern Agency, Ludwigsburg, Germany All Photos © LWF/Erick Coll unless otherwise indicated © 2010 The Lutheran World Federation Printed in Switzerland by SRO-Kundig on paper certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (www.fsc.org) ISBN 978-2-940459-08-7 Contents Foreword .......................................................................................7 Address of the LWF President .......................................................9 Address of the General Secretary ...............................................19 Report of the Treasurer ..............................................................29 Letter to the Member Churches .................................................39 -

Investors Urge Bangladesh Government Not to Abandon the Accord on Fire and Building Safety

Investors Urge Bangladesh Government Not to Abandon the Accord on Fire and Building Safety 250 institutional investors, with over $4 trillion in assets under management, welcomed the formation of the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh (Accord) in May 2013, established to address workplace safety in Bangladesh garment factories following the deaths of 1,134 workers in the Rana Plaza building collapse. The group of investors has consistently supported the Accord throughout the 5 year process at every step. At present, the Bangladesh government is trying to prevent the Accord from operating, putting workers’ safety at risk. In its submission to the Supreme Court regarding the Accord’s appeal against an order that it cease operating in Bangladesh as of November 30, 2018, the Government has stated that the Accord should only be allowed to continue operations under a set of highly restrictive constraints that include prohibiting Accord inspectors from identifying any new safety violations in the factories. Despite significant progress on worker safety measures, the Accord’s work is not completed and the government’s Remediation and Coordination Cell (RCC) does not yet have the capacity nor has it demonstrated the willingness to inspect factories to the same standards. A transition plan for factory inspections, safety trainings, and a worker complaint mechanism will need much more time and genuine engagement by the government. It is vital that the Accord be allowed to continue its inspection and remediation work until that time. The success of the Accord is built on the unprecedented collective action of global brands and trade unions. -

Lutheran – Reformed

The denominational landscape in Germany seems complex. Luthe- ran, Reformed, and United churches are the mainstream Protestant churches. They are mainly organized in a system of regional chur- ches. But how does that look exactly? What makes the German system so special? And why can moving within Germany entail a conversion? Published by Oliver Schuegraf and Florian Hübner LUTHERAN – REFORMED – UNITED on behalf of the Office of the German National Committee A Pocket Guide to the Denominational Landscape in Germany of the Lutheran World Federation Lutheran – Reformed – United A Pocket Guide to the Denominational Landscape in Germany © 2017 German National Committee of the Lutheran World Federation (GNC/LWF) Revised online edition October 2017 Published by Oliver Schuegraf and Florian Hübner on behalf of the Office of the German National Committee of the Lutheran World Federation (GNC/LWF) This booklet contains an up-dated and shortened version of: Oliver Schuegraf, Die evangelischen Landeskirchen, in: Johannes Oeldemann (ed.), Konfessionskunde, Paderborn/Leipzig 2015, 188–246. Original translation by Elaine Griffiths Layout: Mediendesign-Leipzig, Zacharias Bähring, Leipzig, Germany Print: Hubert & Co., Göttingen This book can be ordered for €2 plus postage at [email protected] or downloaded at www.dnk-lwb.de/LRU. German National Committee of the Lutheran World Federation (GNC/LWF) Herrenhäuser Str. 12, 30419 Hannover, Germany www.dnk-lwb.de Content Preface . 5 The Evangelical Regional Churches in Germany . 7 Lutheran churches . 9 The present . 9 The past . 14 The Lutheran Church worldwide . 20 Reformed churches . 23 The present . 23 The past . 26 The Reformed Church worldwide . 28 United churches . -

Eastern Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada Fonds

Eastern Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada Fonds Extent:75.06 m of textual records 123 microfilm reels 2340 photographs 66 audio reels 12 CD ROMs 7 videocassettes Date: 1770-2015, predominant 1862-2015 1 Historical documents 1.0 Background 1.1 Central Canada Synod : incorporation file, 1911 Consists of Letters Patent and Correspondence between lawyers, Province of Ontario Department of the Secretary and Registrar, Synod secretary, and the Constitution and bylaws of the Evangelical Lutheran Synod of Central Canada 1.2 Canada Synod : amendments to Synodical Charter, 1922-1924 Consists of correspondence between church officials and lawyers, documentation pertaining to church property, background information 1.3 Canada Synod : Amendment to Charter; Auxiliary Acts of incorporation in several provinces of the Dominion 1.3.1 Manitoba, 1923-1924 Consists mainly of correspondence 1.3.2 Ontario : Amendment to Charter; Ontario Lutheran Church Act, 1923 Consists of correspondence, petitions, Bill 6, Bill 43 1.4 Evangelical Lutheran Seminary of Canada : file on the Act to amend the Act to Incorporate the Evangelical Lutheran Seminary of Canada, 1926-1927 Consists of Incorporation bills and amendments, 1913, 1923, 1927, correspondence, lawyers, Province of Ontario Legislative Assembly See also : Bill 4 : an act to incorporate Evangelical Seminary of Canada (WLU Archives, U142 F3) See also : Bill 10 : an act respecting the Evangelical Seminary of Canada (WLU Archives, U142 F4) 1.5 Evangelical Lutheran Synod of Canada, Quebec : incorporation file concerning possibility of Quebec incorporation Consists of correspondence, 1925-1926 1.6 United Lutheran Synod of Canada, Special Committee to Review a German translation of the Model Constitution, 1956 : Vorgeschlagene verfassund und nebengesetze fuer gemeinden. -

LWF 2019 Statistics

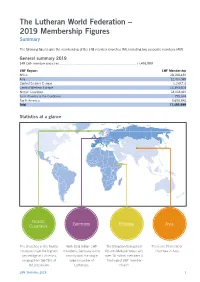

The Lutheran World Federation – 2019 Membership Figures Summary The following figures give the membership of the 148 member churches (M), including two associate members (AM). General summary 2019 148 LWF member churches ................................................................................. 77,493,989 LWF Regions LWF Membership Africa 28,106,430 Asia 12,4 07,0 69 Central Eastern Europe 1,153,711 Central Western Europe 13,393,603 Nordic Countries 18,018,410 Latin America & the Caribbean 755,924 North America 3,658,842 Total 77,493,989 Statistics at a glance Nordic Countries Germany Ethiopia Asia The churches in the Nordic With 10.8 million LWF The Ethiopian Evangelical There are 55 member countries have the highest members, Germany is the Church Mekane Yesus with churches in Asia. percentage of Lutherans, country with the single over 10 million members is ranging from 58-75% of largest number of the largest LWF member the population Lutherans. church. LWF Statistics 2019 1 2019 World Lutheran Membership Details (M) Member Church (AM) Associate Member Church (R) Recognized Church, Congregation or Recognized Council Church Individual Churches National Total Africa Angola ............................................................................................................................................. 49’500 Evangelical Lutheran Church of Angola (M) .................................................................. 49,500 Botswana ..........................................................................................................................................26’023