Leak Detection of Water Supply Networks Using Error-Domain Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leak Test Requirements

METRIC/SI (ENGLISH) NASA TECHNICAL STANDARD NASA-STD-7012 Office of the NASA Chief Engineer Approved: 2019-03-05 LEAK TEST REQUIREMENTS APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE – DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED NASA-STD-7012 DOCUMENT HISTORY LOG Status Document Change Approval Date Description Revision Number Baseline 2019-03-05 Initial Release APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE – DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED 2 of 54 NASA-STD-7012 FOREWORD This NASA Technical Standard is published by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to provide uniform engineering and technical requirements for processes, procedures, practices, and methods that have been endorsed as standard for NASA programs and projects, including requirements for selection, application, and design criteria of an item. This NASA Technical Standard is approved for use by NASA Headquarters and NASA Centers and Facilities, and applicable technical requirements may be cited in contract, program, and other Agency documents. It may also apply to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (a Federally Funded Research and Development Center (FFRDC)), other contractors, recipients of grants and cooperative agreements, and parties to other agreements only to the extent specified or referenced in applicable contracts, grants, or agreements. This NASA Technical Standard establishes uniform use of leak test requirements for NASA vehicles, subsystems and their components, and payloads. This NASA Technical Standard was developed by the Johnson Space Center (JSC) Requirements, Test, and Verification Panel (RTVP) supported by JSC Engineering. To provide additional technical expert guidance, the RTVP established a Technical Discipline Working Group that involved many known space industry experts in leak testing from Glenn Research Center, Kennedy Space Center, Langley Research Center, and Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in particular. -

Outside Diameter Initiated Stress Corrosion Cracking Revised Final White Paper", Developed by AREVA and Westinghouse Under PWROG Program PA-MSC-0474

Program Management Office PWROG 102 Addison Road Connecticut 06095 q .Windsor, ko'ners-- PA-MSC-0474 Project Number 694 October 14, 2010 OG-10-354 U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission Document Control Desk Washington, DC 20555-0001 Subject: PWR Owners Group For Information Only - Outside Diameter Initiated Stress Corrosion Crackin2 Revised Final White Paper, PA-MSC-0474 This letter transmits two (2) non-proprietary copies of PWROG document "Outside Diameter Initiated Stress Corrosion Cracking Revised Final White Paper", developed by AREVA and Westinghouse under PWROG program PA-MSC-0474. This document is being submitted for information only. No safety evaluation (SE) is expected and therefore, no review fees should be incurred. This white paper summarizes the recent occurrences of ODSCC of stainless steel piping identified at Callaway, Wolf Creek and SONGS. Available operating experience (OE) at units that have observed similar phenomena is summarized as well to give a better understanding of the issue. Each of the key factors that contribute to ODSCC was considered along with the reported operating experience to perform a preliminary assessment of areas that may be susceptible to ODSCC. Also a qualitative evaluation was performed to determine whether ODSCC of stainless steel piping represents an immediate safety concern. This white paper is meant to address the issue of ODSCC of stainless steel systems for the near term. I&E guidelines are currently being developed through the PWROG to provide long term guidance. Correspondence related to this transmittal should be addressed to: Mr. W. Anthony Nowinowski, Manager Owners Group, Program Management Office Westinghouse Electric Company 1000 Westinghouse Drive, Suite 380 Cranberry Township, PA 16066 U.S. -

Leak Detection in Natural Gas and Propane Commercial Motor Vehicles Course

Leak Detection in Natural Gas and Propane Commercial Motor Vehicles Course July 2015 Table of Contents 1. Leak Detection in Natural Gas and Propane Commercial Motor Vehicles Course ............................................... 1 1.1 Introduction and Overview ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Welcome ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Course Goal .................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.4 Training Outcomes ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.5 Training Outcomes (Continued) ..................................................................................................................... 2 1.6 Course Objectives .......................................................................................................................................... 2 1.7 Course Topic Areas ........................................................................................................................................ 2 1.8 Course Overview ............................................................................................................................................ 2 1.9 Module One: Overview of CNG, LNG, -

Liquid Copper™ Block Seal Intake & Radiator Stop Leak

RISLONE TECHNICAL BULLETIN Tech Bulletin #: TB-31109-2 Page 1 of 2 st Date 1 Issued: February 13, 2009 Date Revised: November 10, 2016 Rislone® Liquid Copper™ Block Part #: 31109 ISO 9001 CERTIFIED Seal Intake & Radiator Stop Leak ™ LIQUID COPPER BLOCK SEAL INTAKE & RADIATOR STOP LEAK Rislone® Liquid Copper™ Block Seal Intake & Radiator Stop Leak seals larger leaks regular stop leaks won’t. One step formula permanently repairs leaks in gaskets, radiators, heater cores, intake manifolds, blocks, heads and freeze plugs. Use on cars, trucks, vans, SUV’s and RV’s. One “1” Step Sealer contains an antifreeze compatible sodium silicate liquid glass formula, so no draining of the cooling system is required. It will not harm the cooling system when used properly. Use with all types of antifreeze including conventional green or blue (Silicate- based ) and extended life red/orange or yellow (OAT / HOAT) coolant. NOTE: Cooling systems that are dirty or partially clogged should be flushed before usage. DIRECTIONS: 1. Allow engine to cool. Ensure your engine is cool enough so radiator cap can safely be Part Number: 31109 removed. UPC Item: 0 69181 31109 1 2. Shake well. Pour LIQUID COPPER™ BLOCK UPC Case: 1 00 69181 31109 8 SEAL directly into radiator. If using in a small Bottle Size: 510 g cooling system, such as 4 cylinders with no air Bottle Size (cm): 6,6 x 6,6 x 18,8 conditioning, install ½ of bottle. Bottle Cube: 819 TIP: When you don’t have access to the Case Pack: 6 bottles per case radiator cap: for quickest results remove top Case Size (cm): 20,6 x 14 x 20,1 hose where it connects to the top of the Case Cube: 5797 radiator and install product in hose. -

BOILER LIQUID Date: August 2017 Stop-Leak

HCC Holdings, Inc. 4700 West 160th Phone: 800-321-9532 Cleveland, Ohio 44135 Website: www.Oatey.com BOILER LIQUID Date: August 2017 Stop-leak Boiler Liquid Seals and repairs cracks or leaks in steam or hot water heating boilers. Prevents steam boiler surging and will not clog or coat submerged hot water heating coils, controls, vents or valves. Makes a strong, lasting repair on difficult leaks in steam boilers. Tough seal expands and contracts with heat, resists pressure, and is not affected by boiler cleaners. Will not cause priming or foaming. Boiler Liquid combines instantly with water in the boiler. As the water leaks through the crack, it is vaporized and the oxygen in the air transforms the Boiler Liquid into a strong, solid substance. The heat generated by the boiler further hardens the seal. Contains no petroleum distillates and is safe to use in boilers and systems with plastic or rubber components. SPECIFICATIONS: SPECIFICATIONS: Boiler Liquid can be used on new installations to repair leaky joints, sand holes, etc., which may appear after an installation is completed. Ideal for older installations where corrosion causes leaks and cracks that need to be sealed. APPROVALS & LISTINGS Not applicable. SPECIFIC USES Use Boiler Liquid to repair leaks in steam and hot water boilers. SPECIFIC APPLICATIONS* For use on all hydronic systems including those with rubber or plastic components. *For special applications which may not be covered on this or other Oatey literature, please contact Oatey Technical Services Department by phone 1-800-321-9532, or fax 1-800-321-9535, or visit our technical database web-site at www.Oatey.com. -

Protecting Against Vapor Explosions with Water Mist

PROTECTING AGAINST VAPOR EXPLOSIONS WITH WATER MIST J. R. Mawhinney and R. Darwin Hughes Associates, Inc. INTRODUCTION This paper examines a number of practical questions about the possibility of using water mist to mitigate explosion hazards in some industrial applications. Water mist systems have been installed to replace Halon 1301 in gas compressor modules on Alaska’s North Slope oil fields. The hazard in the compressor modules includes fire in lubrication oil lines for the gas turbines that drive the compressors. The hazard also involves the potential for a methane gas leak, ignition, and explosion, although the probabilities of occurrence for the explosion hazard are not the same as the lube oil fire. The performance objective for the original halon systems was to inert the compartment, thus addressing both fire and explosion concerns. The design concentra- tions for the compressor modules were closer to 1.5% than to S%, indicating they were intended to provide an inerting effect. As part of the global move to eliminate ozone-depleting fire sup- pression agents, companies are replacing Halon 1301 systems with water mist systems. The water mist systems were developed and tested for control of liquid fuel or lubricating oil spray or pool fires associated with the turbines that drive the gas compressors. The water mist systems address the most likely hazard, the lube oil fire, hut the inerting benefit provided by Halon I301 has been lost. This has left the question of what to do if there is a methane gas leak unanswered. The question has been asked by the operators of these modules as to whether water mist can provide any benefit for mitigating the gas-air explosion hazard. -

PLUMBING DICTIONARY Sixth Edition

as to produce smooth threads. 2. An oil or oily preparation used as a cutting fluid espe cially a water-soluble oil (such as a mineral oil containing- a fatty oil) Cut Grooving (cut groov-ing) the process of machining away material, providing a groove into a pipe to allow for a mechani cal coupling to be installed.This process was invented by Victau - lic Corp. in 1925. Cut Grooving is designed for stanard weight- ceives or heavier wall thickness pipe. tetrafluoroethylene (tet-ra-- theseveral lower variouslyterminal, whichshaped re or decalescensecryolite (de-ca-les-cen- ming and flood consisting(cry-o-lite) of sodium-alumi earthfluo-ro-eth-yl-ene) by alternately dam a colorless, thegrooved vapors tools. from 4. anonpressure tool used by se) a decrease in temperaturea mineral nonflammable gas used in mak- metalworkers to shape material thatnum occurs fluoride. while Usedheating for soldermet- ing a stream. See STANK. or the pressure sterilizers, and - spannering heat resistantwrench and(span-ner acid re - conductsto a desired the form vapors. 5. a tooldirectly used al ingthrough copper a rangeand inalloys which when a mixed with phosphoric acid.- wrench)sistant plastics 1. one ofsuch various as teflon. tools to setthe theouter teeth air. of Sometimesaatmosphere circular or exhaust vent. See change in a structure occurs. Also used for soldering alumi forAbbr. tightening, T.F.E. or loosening,chiefly Brit.: orcalled band vapor, saw. steam,6. a tool used to degree of hazard (de-gree stench trap (stench trap) num bronze when mixed with nutsthermal and bolts.expansion 2. (water) straightenLOCAL VENT. -

Natural Gas Explosion Kills Seven, Maryland- at 11:55 P.M

NATURAL GAS AND PROPANE FIRES, EXPLOSIONS AND LEAKS ESTIMATES AND INCIDENT DESCRIPTIONS Marty Ahrens Ben Evarts October 2018 Acknowledgements The National Fire Protection Association thanks all the fire departments and state fire authorities who participate in the National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS) and the annual NFPA fire experience survey. These firefighters are the original sources of the detailed data that make this analysis possible. Their contributions allow us to estimate the size of the fire problem. We are also grateful to the U.S. Fire Administration for its work in developing, coordinating, and maintaining NFIRS. To learn more about research at NFPA visit www.nfpa.org/research. E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 617-984-7450 NFPA Index No. 2873 Copyright© 2018, National Fire Protection Association, Quincy, MA This custom analysis is prepared by and copyright is held by the National Fire Protection Association. Notwithstanding the custom nature of this analysis, the NFPA retains all rights to utilize all or any part of this analysis, including any information, text, charts, tables or diagrams developed or produced as part hereof in any manner whatsoever as it deems appropriate, including but not limited to the further commercial dissemination hereof by any means or media to any party. Purchaser is hereby licensed to reproduce this material for his or her own use and benefit, and to display this in his/her printed material, publications, articles or website. Except as specifically set out in the initial request, purchaser may not assign, transfer or grant any rights to use this material to any third parties without permission of NFPA. -

Heat Exchanger Leakage Problem Location

EPJ Web of Conferences 25, 02006 (2012) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/20122502006 © Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2012 HEAT EXCHANGER LEAKAGE PROBLEM LOCATION Jiří HEJČÍK, Miroslav JÍCHAA Abstract: Recent compact heat exchangers are very often assembled from numerous parts joined together to separate heat transfer fluids and to form the required heat exchanger arrangement. Therefore, the leak tightness is very important property of the compact heat exchangers. Although, the compact heat exchangers have been produced for many years, there are still technological problems associated with manufacturing of the ideal connection between the individual parts, mainly encountered with special purpose heat exchangers, e.g. gas turbine recuperators. This paper describes a procedure used to identify the leakage location inside the prime surface gas turbine recuperator. For this purpose, an analytical model of the leaky gas turbine recuperator was created to assess its performance. The results obtained are compared with the experimental data which were acquired during the recuperator thermal performance analysis. The differences between these two data sets are used to indicate possible leakage areas. 1. INTRODUCTION Modern heat exchangers are very demanding from the technological point of view. They are usually assembled from hundreds of parts made of various materials and joined together by various methods (e.g. mechanical bonding, welding, brazing) to form a heat exchanger core. The technology used when assembling the heat exchanger has the main impact on its performance in such cases in which the heat exchanger tightness is probably the most important parameter. Although, there is plenty of experience with very well tested technological processes for production n of tight heat exchangers in huge series, there are still leakage problems with a heat exchanger produced for special purposes in small quantities. -

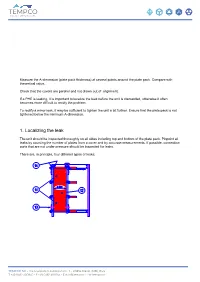

Plate Heat Exchanger, the Reason Is Probably a Hole/Crack in a Plate Caused by Corrosion Or Mechanical Damage

Measure the A-dimension (plate pack thickness) at several points around the plate pack. Compare with theoretical value. Check that the covers are parallel and not drawn out of alignment. If a PHE is leaking, it is important to localize the leak before the unit is dismantled, otherwise it often becomes more difficult to rectify the problem. To rectify a minor leak, it may be sufficient to tighten the unit a bit further. Ensure that the plate pack is not tightened below the minimum A-dimension. 1. Localizing the leak The unit should be inspected thoroughly on all sides including top and bottom of the plate pack. Pinpoint all leaks by counting the number of plates from a cover and by accurate measurements. If possible, connection ports that are not under pressure should be inspected for leaks. There are, in principle, four different types of leaks: TEMPCO Srl - Via Lavoratori Autobianchi, 1 - 20832 Desio (MB) Italy T +39 0362 300830 - F +39 0362 300253 - E [email protected] - W tempco.it 1.1. Leakage through the leakage vent: The most common reason for this type of leakage is gasket failure; either the ring or the diagonal gasket. If the gaskets are in good condition and correctly located in the gasket grooves, check for possible corrosion in the areas between the ring and diagonal gasket by visual inspection or dye penetration. 1.2. If a leakage occurs over a gasket on the side of a plate pack at any position excluding the ones described in 1.1, the gasket and its correct location in the gasket groove should be inspected. -

Controlling Heat Exchanger Leaks

Application Data Sheet ADS 43-020/rev.D Theory January 2011 Controlling Heat Exchanger Leaks BACKGROUND of contamination for boiler feedwater because the condensate has very low conductivity (under 10 Energy costs continue to impact the bottom line at µS/cm) and even a small leak of process water will many industrial plants. Wherever possible, heat sharply increase the reading. More conductive liquids exchangers are used to capture waste heat for reuse can be monitored by pH measurement if the other side in other areas. The capital cost of a heat exchanger is of the heat exchanger contains an acid or base of a compensated by reduced fuel costs over the lifetime different strength. In cases where process conditions of the heat exchanger. can change, measurements before and after the heat Corrosion and eventual leakage in heat exchangers exchanger can be used to isolate possible leaks. can have several undesirable effects. A concentrated process stream may leak into cooling water that is discharged into a lake or river, causing pollution. INSTRUMENTATION Process water, used to condense steam to feed a The Model 1056 Analyzer is an ideal instrument for large boiler, may leak into the condensate and controlling leaks. When the reading (conductivity or severely damage the boiler. In non-critical applica- pH) reaches the alarm setpoint, a relay in the instru- tions, corrosion is a problem because a corroded heat ment will close a set of normally open contacts. These exchanger is less efficient and energy is wasted. contacts can be used to activate an audible alarm, a Engineers use a heat balance to calculate the efficiency control room annunciator, and/or a three-way valve of a heat exchanger, but a small leak actually that diverts the flow of contaminated liquid to a holding “appears” to improve heat transfer (although the area. -

Leak Rate Definition

Leak Rate Definition LEAK RATE Leak rate is affected by the pressure difference (inlet vs outlet), the type of gas that is leaking and the flow characteristics of the leak path. In terms of units, a leak rate can be defined in different ways, but if the SI units are used, then this is expressed in mbar·litre/second. 1 mbar·litre/sec is the amount of gas necessary to be removed from a 1 litre container in 1 second to reduce the pressure by 1mbar. More generally, the gas flow produced by a leak in a container can be defined as follows: Where ∆p is the difference between the internal pressure and the external pressure, ∆t is the time, and V is the volume of the container itself. The units can be changed using specific conversion factors. Example: What is the leak rate for a football with the following characteristics? . Diameter: 22cm . Pressure: 1.9bar . The football is flat after 1 month (internal pressure = external pressure) V = = 5.575·10-3 m3 ∆p = 1900 – 1000 = 900mbar ∆t = 1month = 3600·24·30 = 2.592·106 seconds Q = 1.935·10-6 mbar·litre/sec Tel.: (UK): +44 (0)161 866 88 60 - (US): +1 734 4874566 [email protected] www.vac-eng.com Leak Rate Definition DIFFERENT LEAK RATES FOR DIFFERENT GASES Different gases have different values of viscosity; therefore the leak rate from an orifice of given geometry in the unit of time will be different if the leaking gas is helium or hydrogen for example. In laminar flow conditions, the equation linking leak rates of different gases is the following: Q1 = Q2 In molecular flow conditions instead, the equation is: Q1 = √ Q2 Where Q represents the leak rate of the two gases, and 휂 is the relative viscosity.