A Case Study of Pope Francis' Organizational Culture Change Init

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elizabeth R. Schiltz Associate Professor of Law

SCHOOL OF LAW Legal Studies Research Paper Series WEST, MACINTYRE AND WOJTYŁA: POPE JOHN PAUL II’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF A DEPENDENCY-BASED THEORY OF JUSTICE 45 Journal of Catholic Legal Studies 369 (2007) Elizabeth R. Schiltz Associate Professor of Law University of St. Thomas School of Law Legal Studies Research Paper No. 06-27 This paper can be downloaded without charge from The Social Science Research Network electronic library at: http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=923209 A complete list of University of St. Thomas School of Law Research Papers can be found at: http:// http://www.ssrn.com/link/st-thomas-legal-studies.html CP_SCHILTZ 3/13/2007 3:28:24 AM WEST, MACINTYRE, AND WOJTYŁA: POPE JOHN PAUL II’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF A DEPENDENCY- BASED THEORY OF JUSTICE ELIZABETH R. SCHILTZ† In recent decades, a strand of feminist theory variously referred to as “care feminism,” “cultural feminism,” or “relational feminism” has been arguing for a social re-evaluation of what has traditionally been regarded as “women’s work”—the care of dependents, such as children and elderly or disabled family members. As part of that project, a number of feminists have suggested that the traditional liberal theory of justice, based on the ideal of autonomous, independent actors, should be rejected, or at least revised to reflect the reality of dependency in the life of every individual. Recent books offering such alternative, dependency-based theories of justice include: Joan Tronto, Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care;1 Eva Feder Kittay, Love’s Labor;2 Robin L. -

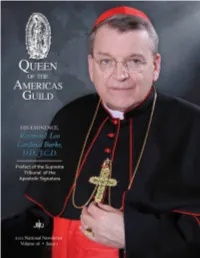

2012 Newsletter

Queen of the Americas Guild 1 From the President…. Another year has come and As much as most of us hate change, sometimes we are gone, and somehow it is time forced to adapt. This past year has been a challenging again to check in with the one personally for myself and my wife, Beverly. We devoted members of the Queen have both dealt with some health issues, especially of the Americas Guild. While Beverly, which has forced us to slow down and re- some things remain the same (a evaluate some things. We have not been able to devote difficult economy for non-profits, as much time as usual to the Guild or our business. We continued association with the also know that we can depend on Rebecca Nichols, Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe Guild National Coordinator, to take care of the day-to- in La Crosse), there are definitely day operations of the Guild. However, there is a silver some changes afoot. lining. Our son, Christopher, has agreed to join the Guild’s Board of Directors (pending board approval). Our retreat center near the Basilica in Mexico City is Christopher has been associated with the Guild in not yet a reality and the work towards it continues. an unofficial way for virtually his entire life, joining However, there has been some promising activity us on pilgrimage and going to Guild events since he on that front; more positive than we have had in was a small child. He is keenly aware of the goals of many years. -

Membres Participants Du Synode Sur La Famille

Membres participants du Synode sur la famille Voici la liste complète et définitive des participants à la XIV Assemblée générale ordinaire du Synode des Évêques (4-25 octobre): A. Les Pères synodaux selon la nature de leur mandat I. PRÉSIDENT Le Saint-Père II. SECRÉTAIRE GÉNÉRAL Le Cardinal Lorenzo Baldisseri III. PRÉSIDENTS DÉLÉGUÉS Le Cardinal André Vingt-Trois, Archevêque de Paris (France) Le Cardinal Luis Antonio G. Tagle, Archevêque de Manille (Philippines) Le Cardinal Raymundo Damasceno Assis, Archevêque d'Aparecida (Brésil) Le Cardinal Wilfrid Fox Napier, OFM, Archevêque de Durban (Afrique du Sud) IV. RAPPORTEUR GÉNÉRAL Le Cardinal Péter Erdö, Archevêque d'Esztergom-Budapest et Président de la Conférence épiscopale (Hongrie), Président du Conseil des Conférences épiscopales d'Europe V. SECRÉTAIRE SPÉCIAL Mgr.Bruno Forte, Archevêque de Chieti-Vasto (Italie) VI. COMMISSION POUR L'INFORMATION Président: Mgr.Claudio Maria Celli, Président du Conseil pontifical pour les communications sociales Secrétaire: Le P.Federico Lombardi, Directeur de la Salle de Presse du Saint-Siège VII. Des églises catholiques orientales Synode de l'Eglise copte ex officio: SB Isaac Ibrahim Sedrak, Patriarche d'Alexandrie Synode de l'Eglise melkite ex officio: SB Grégoire III Laham, BS, Patriarche d'Antioche élu: Mgr.Georges Bacouni, Archevêque de Akka Synode de l'Eglise syriaque ex officio: SB Ignace Youssif III L'Abbéma Younan, Patriarche d'Antioche Synode de l'Eglise maronite ex officio: SB le Cardinal Béchara Boutros carte Raï, OMM, Patriarche d'Antioche -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS OF SCANDINAVIA ON THEIR VISIT AD LIMINA APOSTOLORUM Saturday, 5 April 2003 Dear Brother Bishops, 1. "Grace, mercy, and peace from God the Father and Christ Jesus our Lord" (1 Tim 1:2). With fraternal affection I warmly welcome you, the Bishops of Scandinavia. Your first visit ad Limina Apostolorum in this new millennium is an occasion to renew your commitment to proclaim ever more courageously the Gospel of Jesus Christ in truth and love. As pilgrims to the tombs of the Apostles Peter and Paul, you "come to see Peter" (cf. Gal 1:18) and his collaborators in the service of the universal Church. You thus confirm your "unity in the same faith, hope and charity, and more and more recognize and treasure that immense heritage of spiritual and moral wealth that the whole Church, joined with the Bishop of Rome by the bond of communion, has spread throughout the world" (Pastor Bonus, Appendix I, 3). 2. As Bishops, you have been endowed with the authority of Christ (cf. Lumen Gentium, 25) and entrusted with the task of bearing witness to his saving Gospel. The faithful of Scandinavia, with great expectation, look to you to be steadfast teachers of the faith, selfless in your readiness to speak the truth "in season and out of season" (2 Tim 4:2). By your personal witness to the living mystery of God (cf. Catechesi Tradendae, 7), you make known the boundless love of him who has revealed himself and his plan for humanity through Jesus Christ. -

Archdiocese of Los Angeles Clergy Change List July 1, 2021

Archdiocese of Los Angeles Clergy Change List July 1, 2021 Effective Date Current Assignment Assignment Title Prior Assignment 7/1/2021 Reverend Miguel Angel Acevedo Administrator Administrator Pro Tem St. Paul Catholic Church Our Lady of Victory Church 1920 South Bronson Avenue Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90018-1093 (323) 730-9490 7/1/2021 Reverend Porfirio R. Alvarez Retired Resident Living Privately Our Lady of the Rosary Church Paramount 7/1/2021 Reverend James M. Anguiano Vicar for Clergy Associate Vicar for Clergy Archdiocesan Catholic Center ACC 3424 Wilshire Boulevard Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90010-2241 (213) 637-7284 7/1/2021 Reverend Mario Arellano Associate Pastor Pastor St. John Neumann Catholic Church San Francisco Church 966 West Orchard Street Los Angeles Santa Maria, CA 93458-2028 (805) 922-7099 7/1/2021 Reverend Isaac David Arrieta Associate Pastor Associate Pastor St. Rose of Lima Catholic Church St. Paul Catholic Church 4450 East 60th Street Los Angeles Maywood, CA 90270-3198 (323) 560-2381 7/1/2021 Reverend Jorge Cruz Avila, M.G. Pastor Resident St. Martha Catholic Church Guadalupe Missioners 6019 Stafford Avenue Procure Huntington Park, CA 90255 Los Angeles (323) 585-0386 7/1/2021 Reverend Patrick Ayala Associate Pastor Transitional Deacon Santa Clara Catholic Church 323 South 'E' Street Oxnard, CA 93030-5835 (805) 487-3891 7/1/2021 Reverend Monsignor Albert M. Bahhuth Pastor Sabbatical Holy Family Catholic Church 1527 Fremont Avenue South Pasadena, CA 91030-3736 (626) 799-8908 7/1/2021 Reverend Charles Balamaze Associate Pastor Associate Pastor St. Lorenzo Ruiz Catholic Church St. -

John Paul II, Encyclical, Laborem Exercens (On Human Work), 1981

John Paul II, encyclical, Laborem exercens (On Human Work), 1981 11. Dimensions of the Conflict . I must however first touch on a very important field of questions in which [the Church’s] teaching has taken shape in this latest period, the one marked and in a sense symbolized by the publication of the Encyclical Rerum Novarum [by Leo XIII in 1891]. Throughout this period [beginning with the industrial revolution], which is by no means yet over, the issue of work has of course been posed on the basis of the great conflict that in the age of, and together with, industrial development emerged between "capital" and "labour", that is to say between the small but highly influential group of entrepreneurs, owners or holders of the means of production, and the broader multitude of people who lacked these means and who shared in the process of production solely by their labour. The conflict originated in the fact that the workers put their powers at the disposal of the entrepreneurs, and these, following the principle of maximum profit, tried to establish the lowest possible wages for the work done by the employees. In addition there were other elements of exploitation, connected with the lack of safety at work and of safeguards regarding the health and living conditions of the workers and their families. This conflict, interpreted by some as a socioeconomic class conflict, found expression in the ideological conflict between liberalism, understood as the ideology of capitalism, and Marxism, understood as the ideology of scientiflc socialism and communism, which professes to act as the spokesman for the working class and the worldwide proletariat. -

Director of Development Development Opportunity

Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe March, 2021 DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY The Director of Development is the principal development officer of the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe. He or she is responsible for directing all development activities in coordination with the Executive Director and Board of Directors, including the Shrine’s Founder and Chairman of the Board, Raymond Leo Cardinal Burke. The Director of Development is charged with building the material resources of the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in order to enable the Shrine to fulfill its spiritual mission. The Shrine is funded entirely by private donors who believe in and support our mission of leading souls to Christ through Our Lady of Guadalupe and her message. More than 40,000 donors have supported the Shrine since its inception. Pilgrims and donations come from all 50 States and over 70 different countries. Our development office raises approximately $1.5 million in unrestricted contributions per year, much of which comes from the Cardinal's Annual Appeal. The most recent capital campaign, Answering Mary’s Call, raised $13 million. The next capital campaign will raise money for a 50,000 square foot, 33-room, retreat house, which will allow pilgrims to remain on the Shrine grounds for days of prayer and retreat. MISSION The Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in La Crosse, Wisconsin serves the spiritual needs of those who suffer poverty in body and soul. Faithful to the message of the Blessed Virgin Mary in her appearances on the American continent in 1531, the Shrine It is a place of ceaseless prayer for the corporal and spiritual welfare of God’s children, especially those in most need. -

The Practice of Law As Response to God's Call

The Practice of Law as Response to God's Call Susan J. Stabile* INTRODUCTION My writing in recent years has explored the question o f what Catholic social thought and Catholic legal theory add to our considera- tion of various legal questions. That project proceeds from the premise that faith and religion are not to be relegated to church on Sunday (or temple on Saturday, or other equivalents); rather, faith and religion are relevant to our actions in the world. In the words of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith,' "There cannot be two parallel lives in [a Cath- olic's] existence: on the one hand, the so-called 'spiritual life,' with its values and demands; and on the other, the so-called 'secular' life, that is, life in a family, at work, in social responsibilities, and in the responsibili- ties of public life and in culture." 2th olAicissm is aIn 'in cahmaationval faeith ' that sees God in everything, and the oGosbpel sis ae livirng vmesesagde, in tended to be infused into the reality of the eworlld ins whiech wwe livhe." e r e3 , t" Robert andC Marion Shorta Distinguished Chair in Law, University of St. Thomas School of Law; -Fellow, Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership; Affiliate Senior Fellow. St. John's University Vin- centian Center for Church and Society; Research Fellow. New York University School of Law. Center for Labor and Employment Law; JD. 1982, New York University School of Law; B.A. 1979, Georgetown University. This Article is an expanded version of my presentation at the Seattle Uni- versity School of Law's March 7, 21)08 Symposium, Pluralism. -

Page 1 of 2 Cardinal Pell Hopes for a Pope Who Knows How to Govern

Cardinal Pell hopes for a Pope who knows how to govern - Vatican Insider Page 1 of 2 LANGUAGE: Italiano English Español www.vaticaninsider.com The Pope’s speeches :: Tuesday 05 March 2013 :: Home :: News :: World News Inquiries and Interviews :: The Vatican :: Agenda :: About us SEARCH 03/ 4/2013 OTHER NEWS Cardinal Wuerl is looking above all for a Cardinal Pell hopes for a Pope who knows how to govern Pope with a spiritual vision 14 Like 101 5 America’s Cardinal Wuerl is looking for a pope with a spiritual vision who can... When Australia’s Cardinal George Pell goes into the conclave to elect the new Pope he will be looking for a candidate that is Cardinal Toppo: “It is the Church that a strategist, a decision maker, has good and proven pastoral produces the Pope” qualities, and the ability to govern India has five cardinal electors in the Conclave. Cardinal Toppo talks about... GERARD O'CONNELL ROME Benedict XVI's parting gift: First ostension of Holy Shroud since 1975 to take... Cardinal George Pell, 71, the Archbishop of Sydney, participated in the 2005 This coming 30 March the Holy Shroud will conclave which elected Benedict XVI and is now in Rome again to vote in the be broadcast live on television for... conclave to elect his successor. Diaz: “Cardinal Mahony should reflect on the example set by the Pope” In this interview at Domus Australia he reflects on the resignation of Benedict “Vatican Insider” interviews the former U.S. XVI and speaks about the major challenges facing the Church today ambassador to the Holy See, Miguel.. -

The Importance of the Catholic School Ethos Or Four Men in a Bateau

THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS OR FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ruth Joy August 2018 A dissertation written by Ruth Joy B.S., Kent State University, 1969 M.S., Kent State University, 2001 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2018 Approved by _________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Natasha Levinson _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Averil McClelland _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Catherine E. Hackney Accepted by _________________________, Director, School of Foundations, Leadership and Kimberly S. Schimmel Administration ........................ _________________________, Dean, College of Education, Health and Human Services James C. Hannon ii JOY, RUTH, Ph.D., August 2018 Cultural Foundations ........................ of Education THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS. OR, FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU (213 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Natasha Levinson, Ph. D. Dozens of academic studies over the course of the past four or five decades have shown empirically that Catholic schools, according to a wide array of standards and measures, are the best schools at producing good American citizens. This dissertation proposes that this is so is partly because the schools are infused with the Catholic ethos (also called the Catholic Imagination or the Analogical Imagination) and its approach to the world in general. A large part of this ethos is based upon Catholic Anthropology, the Church’s teaching about the nature of the human person and his or her relationship to other people, to Society, to the State, and to God. -

In Opening Arguments, Cardinal Pell's Lawyers Make His Case for Appeal

In opening arguments, Cardinal Pell’s lawyers make his case for appeal The legal team for Australian Cardinal George Pell set out its case for appeal at the Supreme Court of Victoria Wednesday morning. Judges heard the opening arguments for the defence as they sought leave to appeal. Bret Walker, arguing on June 4, told the three-judge Court of Appeal, led by Chief Justice Anne Feguson, that Pell was seeking leave to appeal on the grounds that his conviction by a jury was “unsafe.” In a controversial verdict, the cardinal was convicted on Dec. 11 of five counts of sexual abuse of minors. Pell’s legal team is seeking appeal on three separate grounds, the first of which is that a guilty verdict was returned despite the lack of proof beyond reasonable doubt. If successful, an appeal on that ground would see Pell’s conviction overturned and the cardinal set free. In March, Pell was sentenced to six years in prison. The secondary appeals, made on more procedural grounds, could lead to a retrial if successful. At the opening of the two-day hearing, Justice Ferguson noted that the judges had reviewed the evidence from the trial, visited Melbourne’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and inspected the vestments Pell is alleged to have been wearing at the time of the supposed abuse. Ferguson explained that the purpose of the hearing was not to re-litigate the trial, or for the defence or prosecution to present the whole of its argument, which had been submitted in writing. Walker argued that the evidence used to convict Pell was clearly insufficient to allow the jury to reach a unanimous finding of guilt beyond reasonable doubt. -

Jesus and the World of Grace, 1968-2016: an Idiosyncratic Theological Memoir William L

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Dayton University of Dayton eCommons Religious Studies Faculty Publications Department of Religious Studies 12-2016 Jesus and the World of Grace, 1968-2016: An Idiosyncratic Theological Memoir William L. Portier University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/rel_fac_pub Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons eCommons Citation Portier, William L., "Jesus and the World of Grace, 1968-2016: An Idiosyncratic Theological Memoir" (2016). Religious Studies Faculty Publications. 125. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/rel_fac_pub/125 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JESUS AND THE WORLD OF GRACE, 1968-2015 AN IDIOSYNCRATIC THEOLOGICAL MEMOIR1 William L. Portier University of Dayton In a well-known passage in the Introduction to Gaudium et Spes, the council reminds the church of its “duty in every age of examining the signs of the times and interpreting them in light of the gospel” (para. 4). The purpose of this is to “offer in a manner appropriate to each generation replies to the continual human questionings on the meaning of this life and the life to come and on how they are related.” In this passage, the church reads the signs of the times to help “continue the work of Christ who came into the world to give witness to the truth, to save and not to judge, to serve and not to be served” (para.