FT Series Photo London 2019 a Conversation with Stephen Shore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Road Trip Journal by Stephen Shore

Steven Shore: A Road Trip Journal by Stephen Shore Ebook Steven Shore: A Road Trip Journal currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Steven Shore: A Road Trip Journal please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Hardcover:::: 256 pages+++Publisher:::: Phaidon Press Inc.; Limited Collectors Ed edition (June 25, 2008)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0714848018+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0714848013+++Product Dimensions::::12 x 2.1 x 17.2 inches++++++ ISBN10 0714848018 ISBN13 978-0714848 Download here >> Description: Stephen Shore is one of the most influential photographers of the twentieth century, best known for his photographs of vernacular America taken in the early 1970s two bodies of work entitled American Surfaces and Uncommon Places. These projects paved the way for future photographers of the ordinary and everyday such as Martin Parr, Thomas Struth, and Nan Goldin. Shore is one of the most important artists working today, and his prints are included in collections of eminent museums and galleries around the world.On July 3, 1973, Stephen Shore set out on the road again. This road trip marked an important point in his career, as he was coming to the tail end of American Surfaces and embarking on a body of work that is known as Uncommon Places. While traveling, in addition to taking photographs, Shore also distributed a set of postcards that he had made and printed himself. While passing through Amarillo, Texas, Shore selected ten of his own photographs of places of note, such as Dougs Barb-B- Que and the Potter County Court House, and designed the back of the cards to look like a typical generic postcard. -

Faltblatt Retrospective.Indd

Mexico, 1963 London, England, 1966 New York City, 1963 Paris, France, 1967 JOEL New Yok City, 1975 Five more found, New York City, 2001 MEYEROWITZ RETROSPECTIVE curated by Ralph Goertz Sarah, Cape Cod, Cape Sarah, 1981 Roseville Cottages, Truro, Massachusetts, 1976 Bay.Sky, Provincetown, Massachusetts, 1985 1978 City, York New Dancer, Young JOEL MEYEROWITZ RETROSPECTIVE Joel Meyerowitz, born and grown up in New York, belongs to a generation of photographers - together with William Eggleston, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, Stephen Shore, Tony Ray-Jones and Garry Winogrand - who are equipped with a unique sensitivity towards the daily, bright, hustle and bustle on the streets, who are able to grasp a human being as an individual as well as in their social context. Starting in the early 1960s, Joel Meyerowitz went out on the streets, day in, and day out, powered by his passion and devotion to photography, in order to study people and see how photographs described what they were doing. In order to catch the vibes he ranges over the streets of New York, together with Tony Ray-Jones and later with his friend Garry Winogrand. Different from Tony Ray-Jones and Garry Winogrand, Meyerowitz loaded his camera with color film in order to capture life realistically, which meant shooting in color for him. While his first photographs are often determined in a situational way, he starts, early on, putting the subject not only in the centre, but consciously leaving the centre of the picture space free and extending the picture-immanent parts over the whole frame. His dealing with picture space and composition, which consciously differ from those of his idols like Robert Frank and Cartier-Besson, create a unique style. -

Shore, King & Street Fashion

Alec Soth's Archived Blog August 9, 2007 Shore, King & Street Fashion Filed under: vernacular & Flickr — alecsothblog @ 10:30 am I appreciate the flurry of Flickr commentary. I’ve learned a lot. But I’m worried that Stephen Shore has been unfairly criticized. If your read the full context of his comments, he is simply making a case for raw documentation: There has to be on the web a treasure trove of brilliant untutored pictures. I’d seen the photographs that were made at the time of the London Underground bombing by people with cell phones in the Underground cars. And they have an energy to them, and an immediacy, that was pretty extraordinary. They weren’t structurally fine pictures, but, you know, this is a new world. This is people in a subway car that has just been bombed – they flip out their phones and start taking pictures. This is pretty amazing. So I thought, okay, I’m going to find a lot of great stuff and I went onto Flickr and it was just thousands of pieces of shit. I couldn’t believe it. It is just all conventional. It’s all clichés. It is one visual convention after another. Just this week a friend of mine sent me some pictures he’s been collecting on eBay. And they were fabulous. It is just stuff for sale. The difference is that on eBay the people are not trying to make art. They are just trying to show something. ‘This is what this bottle looked like. It is not silhouetted. -

Exegesis. Christopher Shawne Brown East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2008 Exegesis. Christopher Shawne Brown East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Photography Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Christopher Shawne, "Exegesis." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1903. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1903 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXEGESIS A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Art & Design East Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts ________________________ by Christopher Shawne Brown May 2008 ___________________ Mike Smith, Committee Chair Dr. Scott Contreras-Koterbay Catherine Murray M. Wayne Dyer Keywords: photography, family album, color, influence, landscape, home, collector A B S TRACT Exegesis by Christopher Shawne Brown The photographer discusses the work in Exegesis, his Master of Fine Arts exhibition held at Slocumb Galleries, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, Tennessee from October 29 through November 2, 2007. The exhibition consists of 19 large format color photographs representing and edited from a body of work that visually negotiates the photographer’s home in East Tennessee. The formulation of a web of influence is explored with a focus on artists who continue to pertain to Brown’s work formally and conceptually. -

Words Without Pictures

WORDS WITHOUT PICTURES NOVEMBER 2007– FEBRUARY 2009 Los Angeles County Museum of Art CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Charlotte Cotton, Alex Klein 1 NOVEMBER 2007 / ESSAY Qualifying Photography as Art, or, Is Photography All It Can Be? Christopher Bedford 4 NOVEMBER 2007 / DISCUSSION FORUM Charlotte Cotton, Arthur Ou, Phillip Prodger, Alex Klein, Nicholas Grider, Ken Abbott, Colin Westerbeck 12 NOVEMBER 2007 / PANEL DISCUSSION Is Photography Really Art? Arthur Ou, Michael Queenland, Mark Wyse 27 JANUARY 2008 / ESSAY Online Photographic Thinking Jason Evans 40 JANUARY 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Amir Zaki, Nicholas Grider, David Campany, David Weiner, Lester Pleasant, Penelope Umbrico 48 FEBRUARY 2008 / ESSAY foRm Kevin Moore 62 FEBRUARY 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Carter Mull, Charlotte Cotton, Alex Klein 73 MARCH 2008 / ESSAY Too Drunk to Fuck (On the Anxiety of Photography) Mark Wyse 84 MARCH 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Bennett Simpson, Charlie White, Ken Abbott 95 MARCH 2008 / PANEL DISCUSSION Too Early Too Late Miranda Lichtenstein, Carter Mull, Amir Zaki 103 APRIL 2008 / ESSAY Remembering and Forgetting Conceptual Art Alex Klein 120 APRIL 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Shannon Ebner, Phil Chang 131 APRIL 2008 / PANEL DISCUSSION Remembering and Forgetting Conceptual Art Sarah Charlesworth, John Divola, Shannon Ebner 138 MAY 2008 / ESSAY Who Cares About Books? Darius Himes 156 MAY 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Jason Fulford, Siri Kaur, Chris Balaschak 168 CONTENTS JUNE 2008 / ESSAY Minor Threat Charlie White 178 JUNE 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM William E. Jones, Catherine -

Alec Soth in His Photo Book Library

Palumbo, Jacqui. “5 Celebrated Photographers Share Their Favorite Photo Books.” Artsy. December 31, 2019. Alec Soth in his photo book library. Photo by Ethan Jones. All photographers remember the magic of the first camera they owned, but another transformative experience is often the first photography book that kindled a flame within them. Photographers’ books are rarely hidden away or untouched, but rather combed through frequently, and loved. “My photo book collection is arranged in stacks in my living room, in a way that encourages visitors to my home to look and enjoy them,” said documentary photographer Laylah Amatullah Barrayn. Stains, yellowed pages, and worn bindings might make the rare book collector balk. But fine-art photographer Alec Soth often becomes deeply attached to his copies precisely because of their imperfections. “I love the worn parts of them— this clipped corner on [Stephen Shore’s] Uncommon Places,” he said, or a stain on his copy of Robert Adams’s Summer Nights (1985). “It's just the memory and the tactile quality of the book. I remember pulling it from my bookshelf, when I first fell in love with it.” Here, five renowned photographers take us inside their photo book collections. Alec Soth Alec Soth in his photo book library. Photo by Ethan Jones. One of Soth’s earliest photo books was the stained copy of Adams’s Summer Nights. He bought it before he considered his handful of books a collection. Today, he said, “the Robert Adams shelf is a heavy one.” Soth has collected around 5,000 books, but he still doesn’t consider what he does “collecting” in a formal sense. -

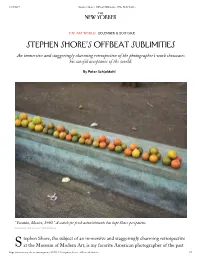

Stephen Shore's Offbeat Sublimities

12/4/2017 Stephen Shore’s Offbeat Sublimities | The New Yorker The Art World December 11, 2017 Issue Stephen Shore’s Offbeat Sublimities An immersive and staggeringly charming retrospective of the photographer’s work showcases his easeful acceptance of the world. By Peter Schjeldahl “Yucatán, Mexico, 1990.” A search for fresh astonishments has kept Shore peripatetic. Courtesy the artist / 303 Gallery tephen Shore, the subject of an immersive and staggeringly charming retrospective S at the Museum of Modern Art, is my favorite American photographer of the past https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/12/11/stephen-shores-offbeat-sublimities 1/7 12/4/2017 Stephen Shore’s Offbeat Sublimities | The New Yorker half century. This is not purely a judgment of quality. Shore has peers in a generation that, in the nineteen-seventies, stormed to eminence with color lm, which art photographers had long disdained, and, often, with a detached scrutiny of suburban sprawl, woebegone towns, touristed nature, cars (always cars), and other familiar and banal, accidentally beautiful, cross-country phenomena. The closest to Shore, in a cohort that includes Joel Meyerowitz, Joel Sternfeld, and Richard Misrach, is his friend William Eggleston, the raffish Southern aristocrat who has made pictures unbeatably intense and iconic: epiphanies triggered by the hues and textures of a stranded tricycle, say, or of a faded billboard in a scrubby eld. While similarly alert to offbeat sublimities, Shore is a New Yorker more receptive than marauding in attitude. I fancy that Eggleston is the cavalier Mephistopheles of American color photography, and Shore the discreet angel Gabriel. -

00 Paa Intro 6-19

Introduction Nearly two centuries after the technology was first invented in the 1830s, photography has come of age as a contemporary art form. In the 21st century the art world has fully embraced the photograph as a legitimate medium, equal in status to painting and sculpture, and photographers frequently display their work in art galleries and illustrated fine-art monographs. In light of these exciting developments, this book is intended to provide an introduction to and overview of the field of photography as contemporary art, with the aim of defining it as a subject and identifying its characteristic features and themes. If there is a single, overarching idea of contemporary photography in this book, it is the wonderful pluralism of this creative field. The selection of nearly 250 photographers whose work is illustrated in these pages aims to convey a sense of the broad and intelligent scope of contemporary photography. While it includes the handful of well-known photographers who hold permanent residence in the pantheon of contemporary art, it intentionally treats contemporary art photography as fundamentally diverse in both form and intent, involving the cumulative efforts of many independent practitioners, most of whom are not well known outside their immediate spheres of practice. Every photographer represented here shares a commitment to making their own contribution to the physical and intellectual space of culture. In its most literal interpretation, this means that all of the photographers in this book create work that is intended to be displayed on gallery walls and in the pages of art books. It is important to bear in mind that most of the photographers are represented only by a single image, invariably selected to stand for their entire body of work. -

Stephen Shore

Stephen Shore Biographie / Biography geboren / born in 1947 in New York, USA lebt und arbeitet / lives and works in New York and Tivoli, NY, USA Lehrstühle / Teaching Positions 1996-2000 Bard College, New York, USA; Chairman, Arts Division since 1982 Bard College, New York, USA; Susan Weber Professor in the Arts; Director, Photography Program Preise und Stipendien / Awards and Fellowships 2019 The Lucie Awards. Achievement in Fine Art 2019 Master of Photography, Photo London 2010 Royal Photographic Society, Honorary Fellow 2010 German Photographic Society, Culture Prize 2005 Deutsche Börse Photography Prize, finalist 2005 Aperture - Award 1993 MacDowell Colony, New Hampshire, USA 1980 American Academy in Rome, IT 1979 National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, USA 1977 National Endowment for the Artsbook, Publishing Grant 1975 Guggenheim Foundation, New York, USA 1974 National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, USA Einzelausstellungen (Auswahl) / Selected solo exhibitions 2019 Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles, USA ‘Master of Photography,’ Photo London, Somerset House, London, UK 2018 303 Gallery, New York, USA 2017 Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA 2016 ‘Stephen Shore’, Camera, Centro Italiano per Fotografia, Turin, IT ‘Stephen Shore: Retrospective’, Huis Marseille, Amsterdam, NL ‘Stephen Shore: Retrospective’, C/O BERLIN, Berlin, DE 2015 ‘Stephen Shore: Retrospective’, Gijon Museum, Gijon, ES ‘Stephen Shore: Retrospective’, Espace Van Gogh, Les Rencontres D’Arles, Arles, FR 2014 ‘Stephen Shore: Retrospective’, Fundacion MAPFRE, Madrid, ES 303 Gallery, New York, USA 2013 ‘SOMETHING + NOTHING’, Sprüth Magers, London, GB 2012 ‘Uncommon Places’, Photobiennale, Moscow, RU 2011 'Stephen Shore', Aspen Art Museum, Aspen, USA 'Stephen Shore: Uncommon Places', Autostadt Wolfsburg, DE 2010 'Uncommon Places', Sprüth Magers, Berlin, DE 'Biographical Landscape. -

The Art of Color: Photography from Stieglitz to Sherman at Milwaukee Art Museum Curtis Carter Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Philosophy Faculty Research and Publications Philosophy, Department of 2-26-2013 The Art of Color: Photography from Stieglitz to Sherman at Milwaukee Art Museum Curtis Carter Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Published in the newspaper entitled "Shepherd Express: Express Milwaukee." February 26, Art (2013): 28. Permalink. © 2013 Shepherd Express. Used with permission. The Art of Color Photography from Stieglitz to Sherman at Milwaukee Art Museum By Curtis L. Carter Shepherd Express (Express Milwaukee), February 26, 2013 For most viewers today, color photography is taken for granted in art as in everyday life. This was not always the case, as documented in the Milwaukee Art Museum’s exhibition “Color Rush” (through May 19). The curators interpret the history of color photography using familiar magazine and newspaper images alongside original photographs. Hollywood movie posters and film clips, and even a slide show depicting Depression-era Farm Security Administration photos not initially released to the public, contribute to the story. What was required to change skeptical views concerning color photography as art? First was the invention of color image-making processes, and then making color photography familiar and affordable with the aid of Kodachrome film and other means. “Color Rush” begins with 1907 autochrome glass plate photographs by Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen and continues through contemporary reflexive art images by Cindy Sherman and Nan Goldin. The exhibition is organized pedagogically into four main sections: “Early Automatic Color” covers pioneering experiments by Stieglitz, Steichen and National Geographic; “Consuming Color” takes in commercial uses of color images in Life, Vogue and Hollywood posters; “Choosing Color” showcases the color photography of leading American artists beginning in the 1940s; and “An Explosion of Color” brings art photography from the aftermath of World War II into postmodernism. -

To What Extent Did the New Topographic Movement Reflect Changing Attitudes Towards Landscape Photography?

Laura Aldington To what extent did the new topographic movement reflect changing attitudes towards landscape photography? “Landscape photographs can offer us, I think, three truths- geography, if taken on its own, is sometimes boring, autobiography is frequently trivial, and metaphor can be dubious. But taken together... the three kinds of information strengthen each other and reinforce what we all work to keep in tact- an affection for life.”1 This essay will explore the genre of landscape photography, in particular focusing on the New Topographic movement. The aim of the essay is to evaluate and asses to what extent the New Topographic movement reflects the changing attitudes towards landscape photography. Within this it will therefore come across several other important questions, looking into what is perceived as a landscape, whether aspects of landscape photography may have changed and exploring to what extent the new topographic movement had a role to play in this, if at all. As the aim is to look at changing attitudes towards landscape photography, it may also be considered beneficial when answering the question, to explore political and social factors which may have an influence on landscape photography, and the changing ways people perceive it as a genre. Defining 'landscape' tends to be controversial. There is a difference between 'land' and 'landscape'. In principle the land is a natural phenomenon, although land in modern times (particularly in the developing and developed world) tends to be subject to human intervention 2. This can be seen through acts such as the industrial revolution, industrialisation, urban sprawl and deforestation. -

For Immediate Release

For Immediate Release: Upcoming Exhibition Lewis Baltz NEVADA November 15th – December 30th, 2016 Joseph Bellows Gallery is pleaseD to announce its upcominG exhibition, NEVADA by the late American photoGrapher, Lewis Baltz (1945-2014). NEVADA will present the entire portfolio of 15 black and white photographs created by Baltz in 1977. The exhibition will open on November 15th anD continue throuGh December 30th, 2016. Nevada is a central work of Baltz’s continueD interest in the American West anD its changing landscape. The photographs Describe the Development of the desert region of Nevada, near Reno: construction sites and their artifacts, vistas of newly built tract communities, and the desert environments that surrounD their imprint are traceD with the high-key light of the western sun or glow of artificial light illuminatinG the darkness of night. HiDDen Valley, LookinG Southwest, 1977 Lewis Baltz was born in Newport Beach, California in 1945. He receiveD his BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1969 anD his MFA from Claremont GraDuate School in 1971. That same year he was incluDeD in The CroweD Vacancy: Three Los AnGeles PhotoGraphers, an exhibition that also incluDeD Anthony HernanDez anD Terry Wild. Baltz's photographs of the transforminG American lanDscape DefineD a central role in 1970's lanDscape photoGraphy anD influenceD forthcominG Generations of photographic practice. He, along with other notable photographers including Frank Gohlke, Robert Adams, Stephen Shore anD John Schott came to prominence throuGh their inclusion in the groundbreaking and influential exhibition, New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altereD Landscape, an exhibition organizeD at the George Eastman House in 1975.