“UFC Pay-Per-View Buys and the Value of the Celebrity Fighter”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE December 8, 2016 TO: Members, Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade FROM: Committee Majority Staff RE: Hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” I. INTRODUCTION On December 8, 2016, at 10:00 a.m. in 2322 Rayburn House Office Building, the Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade will hold a hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” II. WITNESSES The Subcommittee will hear from the following witnesses: Randy Couture, President, Xtreme Couture; Lydia Robertson, Treasurer, Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports; Jeff Novitzky, Vice President, Athlete Health and Performance, Ultimate Fighting Championship; and Dr. Ann McKee, Professor of Neurology & Pathology, Neuropathology Core, Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Boston University III. BACKGROUND A. Introduction Modern mixed martial arts (MMA) can be traced back to Greek fighting events known as pankration (meaning “all powers”), first introduced as part of the Olympic Games in the Seventh Century, B.C.1 However, pankration usually involved few rules, while modern MMA is generally governed by significant rules and regulations.2 As its name denotes, MMA owes its 1 JOSH GROSS, ALI VS.INOKI: THE FORGOTTEN FIGHT THAT INSPIRED MIXED MARTIAL ARTS AND LAUNCHED SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT 18-19 (2016). 2 Jad Semaan, Ancient Greek Pankration: The Origins of MMA, Part One, BLEACHERREPORT (Jun. 9, 2009), available at http://bleacherreport.com/articles/28473-ancient-greek-pankration-the-origins-of-mma-part-one. -

Like UFC Champion Conor Mcgregor)

Achieve Your Goals Podcast #85 - How To Create Your Own Destiny (Like UFC Champion Conor McGregor) Nick: Welcome, to the Achieve Your Goals Podcast with Hal Elrod. I'm your host Nick Palkowski and you're listening to the show that is guaranteed to help you take your life to the next level faster than you ever thought possible. In each episode you'll learn from someone who has achieved extraordinary goals that most haven't. Is the author of number one best selling book The Miracle Morning, a hall of fame, and business achiever, and international keynote speaker, ultra marathon runner and the founder of vipsuccesscoaching.com. Mr. Hal Elrod. Hal: All right, Achieve Your Goals Podcast. Listeners welcome, this is your host Hal Elrod, and thank you for tuning in to what is sure to be an eye opening and surprisingly fun episode of the Achieve Your Goals Podcast. This will be a little different than anything we've ever done before. I do have a guest. I'm going to wait for a few minutes to tell you who that is. And the topic of the podcast today revolves around my favorite sport and specifically around the number one star, if you will. One of the top fighters in the world. And when it comes to my favorite sport, as many of you may know, I'm a huge fan of the sport known as M-M-A, which stands for Mixed Martial Arts, or what's popularly known as the UFC, which is the kind of the NBA of mix martial arts. -

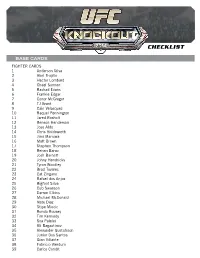

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

Absolute Championship Berkut History+Geography

ABSOLUTE CHAMPIONSHIP BERKUT HISTORY+GEOGRAPHY The MMA league Absolute Championship Berkut was founded in early 2014 on the basis of the fight club “Berkut”. The first tournament was held by the organization on March 2 and it marked the beginning of Grand Prix in two weight divisions. In less than two years the ACB company was able to become one of three largest Russian MMA organizations. Also, a reputable independent website fightmatrix.com named ACB the number 1 promotion in our country. 1 GEOGRAPHY BELGIUM The geography of the tournaments covered GEORGIA more than 10 Russian cities, as well as Tajikistan, Poland, Georgia and Scotland. 50 MMA tournaments, 8 kickboxing ones HOLLAND POLAND and 3 Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu tournaments will be held by the promotion by the end of 2016 ROMANIA TAJIKISTAN SCOTLAND RUSSIA 2 OUR CLIENT’S PORTRAIT AGE • 18-55 YEARS OLD TARGET AGE • 23-29 YEARS OLD 9\1 • MEN\WOMEN Income: average and above average 3 TV BROADCAST Tournaments are broadcast on TV channels Match!Fighter and BoxTV as well as online. Average audience coverage per tournament: - On TV - 500,000 viewers; - Online - 150,000 viewers. 4 Media coverage Interviews with participants of the tournament are regularly published in newspapers and on websites of leading Russian media: SPORTBOX.RU, R- SPORT.RU, CHAMPIONAT.COM, MMABOXING.RU, ALLFIGHT.RU , etc. Foremost radio stations, Our Radio, Rock FM, Sport FM, etc. also broadcast the interviews. 5 INFORMATION SUPPORT Our promotion is also already well known outside Russia. Tournament broadcasts and the main news of the league regularly appear on major international websites: 6 Social networks coverage THOUSAND 400 SUBSCRIBERS 4,63 MILLION VIEWS 7 COMPANY MANAGEMENT The founder of the ACB league is one of the most respected citizens of the Chechen Republic – Mairbek Khasiev. -

BISPING: Barnett Needs to Push the Pace Vs. Nelson

FS1 UFC TONIGHT Show Quotes – 9/23/15 BISPING: Barnett Needs To Push The Pace Vs. Nelson Florian: “Uriah Hall Is Too Dangerous To Just Stand and Trade With” LOS ANGELES – UFC TONIGHT host Kenny Florian and guest host Michael Bisping break down the upcoming FS1 UFC FIGHT NIGHT: BARNETT VS. NELSON. Karyn Bryant and Ariel Helwani add reports. UFC TONIGHT guest host Michael Bisping on how Josh Barnett can beat Roy Nelson: “Josh needs to not get hit by the right hand of Roy. He needs to push the pace of the fight, move forward, and push Roy up against fence and brutalize him with knees and elbows like he did with Frank Mir. Most of his finishes came from the clinch position. He finishes fights against the fence. He did that against Frank Mir.” UFC TONIGHT host Kenny Florian on Barnett avoiding Nelson’s knock out power: “Josh doesn’t want to be on the outside where Roy’s right hand can get him. He wants to be on the inside. He’s been busy on the submission circuit. He’s dangerous on the mat and that’s where he wants to get Roy.” Bisping on how Nelson should fight Barnett: “What Roy can’t get is predictable. If he just tries to throw the big right hand, Barnett is going to see it coming. Roy has to mix up his striking. I’m not sure he’s going to go for takedowns. But he has to mix his striking. His right hand and left hooks, to keep Josh at bay.” Florian on Nelson mixing up his strikes: “The knock on Nelson is his lack of evolution. -

Outside the Cage: the Campaign to Destroy Mixed Martial Arts

OUTSIDE THE CAGE: THE CAMPAIGN TO DESTROY MIXED MARTIAL ARTS By ANDREW DOEG B.A. University of Central Florida, 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2013 © 2013 Andrew Doeg ii ABSTRACT This is an early history of Mixed Martial Arts in America. It focuses primarily on the political campaign to ban the sport in the 1990s and the repercussions that campaign had on MMA itself. Furthermore, it examines the censorship of music and video games in the 1990s. The central argument of this work is that the political campaign to ban Mixed Martial Arts was part of a larger political movement to censor violent entertainment. Connections are shown in the actions and rhetoric of politicians who attacked music, video games and the Ultimate Fighting Championship on the grounds that it glorified violence. The political pressure exerted on the sport is largely responsible for the eventual success and widespread acceptance of MMA. The pressure forced the sport to regulate itself and transformed it into something more acceptable to mainstream America. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 Historiography ........................................................................................................................... -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 4, 2020 [email protected] PANCRASE 316, July 24, 2020 – Studio Coast, Tokyo Bout Hype A

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 4, 2020 PANCRASE 316, July 24, 2020 – Studio Coast, Tokyo Bout Hype After a five-month hiatus, the legendary promotion Pancrase sets off the summer fireworks with a stellar mixed martial card. Studio Coast plays host to 8 main card bouts, 3 preliminary match ups, and 12 bouts in the continuation of the 2020 Neo Blood Tournament heats on July 24th in the first event since February. Reigning Featherweight King of Pancrase Champion, Isao Kobayashi headlines the main event in a non-title bout against Akira Okada who drops down from Featherweight to meet him. The Never Quit gym ace and Bellator veteran, Kobayashi is a former Pancrase Lightweight Champion. The ripped and powerful Okada has a tough welcome to the Featherweight division, but possesses notoriously frightening physical power. “Isao” the reigning Featherweight King of Pancrase Champion, has been unstoppable in nearly three years. He claimed the interim title by way of disqualification due to a grounded knee at Pancrase 295, and following orbital surgery and recovery, he went on to capture the undisputed King of Pancrase belt from Nazareno Malagarie at Pancrase 305 in May 2019. Known to fans simply as “Akira”, he is widely feared as one of the hardest hitting Pancrase Lightweights, and steps away from his 5th ranked spot in the bracket to face Kobayashi. The 33-year-old has faced some of the best from around the world, and will thrive under the pressure of this bout. A change in weight class could be the test he needs right now. The co-main event sees Emiko Raika collide with Takayo Hashi in what promises to be a test of skills and experience, mixed with sheer will-to-win guts and determination. -

The Week Ahead

THE WEEK AHEAD Week of May 11, 2013 – May 17, 2013 Asian Pacific American Heritage Month takes place May 1 – May 30 Saturday, May 11 - The Board of School Trustees seeks the public's input on the superintendent selection process, as well as the direction the district is taking and the reforms under way. Please participate in the online survey at http://ccsd.net/district/superintendent-selection-process/ and join the trustees for a town hall meeting at Western High School’s theater, 4601 W. Bonanza Rd., Las Vegas, at 9:30 a.m. Monday, May 13 - The Board of School Trustees seeks the public's input on the superintendent selection process, as well as the direction the district is taking and the reforms under way. Please participate in the online survey at http://ccsd.net/district/superintendent-selection-process/ and join the trustees for a town hall meeting at Legacy High School’s theater, 150 W. Deer Springs Way, Las Vegas, at 7 p.m. Tuesday, May 14 - Scooter Christensen of the Harlem Globetrotters will visit with students of John Bonner Elementary School at 9:30 a.m. He will talk about S.P.I.N. (Some Playtime Is Necessary), a program designed to make fitness fun for children, while promoting and encouraging an active lifestyle. Christensen lists Las Vegas as his hometown. Bonner Elementary School is located at 765 Crestdale Ln., Las Vegas. For more information, call Ruby Ramirez of the Harlem Globetrotters at (602) 707-7022. Tuesday, May 14 - Jack Lund Schofield Middle School and the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC), will be hosting an anti-bullying program, geared toward sixth and seventh grade students, from 8 - 10:30 a.m. -

Pay-Per-View

Pay-Per-View Don’t bother with the babysitter. Stop worrying about traffic. Because with Pay Per View, you get the best seats in the house without ever leaving home. From UFC fights to exclusive concerts, watch the best in live sports and entertainment right on your own TV. Ordering made easy No need to call or go online. Just order with your remote. From the Guide menu, go to the Pay Per View event channel (PPV) to see what’s playing this month. Once you’ve made your selection, all you need to do is select “Watch” and then confirm your order. It’s that easy. What’s new this month? NWA: When Our Shadows Fall June 6th, 2021, 4:00 p.m. ET / 1:00 p.m. PT On June 6th NWA presents its next live pay per view event, When Our Shadows Fall! The event features wrestlers such as the NWA Worlds Heavyweight Champion Nick Aldis, NWA Television Champion the Pope, NWA Women's World Champion Serena Deeb, and many more! SD standard definition $19.99 HD high definition $19.99 Channels 324 and 611 (BlueCurve TV SD) Channels 300 and 601 (BlueCurve TV HD) Replays: Available until July 06th, 2021 Showtime PPV Boxing: Floyd Mayweather vs Logan Paul June 6th, 2021, 8:00 p.m. ET / 5:00 p.m. PT Hall of Fame boxing legend Floyd Mayweather, one of the greatest fighters of all time, returns to the ring for the first time in nearly four years to face social media giant Logan Paul in an 8-round special exhibition. -

Cultivating Identity and the Music of Ultimate Fighting

CULIVATING IDENTITY AND THE MUSIC OF ULTIMATE FIGHTING Luke R Davis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Megan Rancier, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2012 Luke R Davis All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Megan Rancier, Advisor In this project, I studied the music used in Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) events and connect it to greater themes and aspects of social study. By examining the events of the UFC and how music is used, I focussed primarily on three issues that create a multi-layered understanding of Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) fighters and the cultivation of identity. First, I examined ideas of identity formation and cultivation. Since each fighter in UFC events enters his fight to a specific, and self-chosen, musical piece, different aspects of identity including race, political views, gender ideologies, and class are outwardly projected to fans and other fighters with the choice of entrance music. This type of musical representation of identity has been discussed (although not always in relation to sports) in works by past scholars (Kun, 2005; Hamera, 2005; Garrett, 2008; Burton, 2010; Mcleod, 2011). Second, after establishing a deeper sense of socio-cultural fighter identity through entrance music, this project examined ideas of nationalism within the UFC. Although traces of nationalism fall within the purview of entrance music and identity, the UFC aids in the nationalistic representations of their fighters by utilizing different tactics of marketing and fighter branding. Lastly, this project built upon the above- mentioned issues of identity and nationality to appropriately discuss aspects of how the UFC attempts to depict fighter character to create a “good vs. -

Hit Show Dana White's Contender Series

HIT SHOW DANA WHITE’S CONTENDER SERIES CONTINUES ITS FOURTH SEASON WITH EPISODE 7 AIRING LIVE TUESDAY FROM UFC APEX IN LAS VEGAS Las Vegas – The fourth season of the hit show Dana White’s Contender Series continues with Episode 7, featuring a lineup of rising athletes looking to make their dreams come true by impressing UFC President Dana White and earning a spot on the UFC roster. The seventh episode of season four takes place on Tuesday, September 15 at 8 p.m. ET / 5 p.m. PT, with all five bouts streaming exclusively on ESPN+ in the US. ESPN+ is available through the ESPN.com, ESPNPlus.com or the ESPN App on all major mobile and connected TV devices and platforms, including Amazon Fire, Apple, Android, Chromecast, PS4, Roku, Samsung Smart TVs, X Box One and more. Fans can sign up for $4.99 per month or $49.99 per year, with no contract required. To support your coverage, please find the download link to the season four sizzle reels here and here. In addition, please find the download link for the season four athlete feature here, which highlights some of the participating athletes, their backgrounds and what competing on Dana White’s Contender Series means to them. Season 4, Episode 7 – Confirmed Bouts: Middleweight Gregory Rodrigues vs. Jordan Williams Featherweight Muhammad Naimov vs. Collin Anglin Welterweight Korey Kuppe vs. Michael Lombardo Women’s featherweight Danyelle Wolf vs. Taneisha Tennant Featherweight Dinis Paiva vs. Kyle Driscoll Visit the UFC.com for information and additional content to support your UFC coverage. -

Brooks, UFC, Mars Giving Las Vegas Big Back-To- Back Weekends by Richard N

Brooks, UFC, Mars giving Las Vegas big back-to- back weekends By Richard N. Velotta Las Vegas Review-Journal July 8, 2021 - 11:14 pm Normally, there’s a tourism lull the week after a three-day weekend. But as everyone knows, 2021 is far from normal, and the weekend after the three-day Fourth of July holiday has the makings of a blockbuster for Las Vegas. Credit a supercluster of blockbuster entertainment coming up in the city this weekend. The UFC 264 event at T-Mobile Arena, featuring Conor McGregor-Dustin Poirier. Garth Brooks at Allegiant Stadium. Bruno Mars at Park MGM. On top of that, former President Donald Trump is planning to attend the big fight, UFC President Dana White confirmed Thursday. The Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority doesn’t have any historical data to calculate an estimate of how many people will venture to Las Vegas this weekend, but most observers think more than 300,000 people were in the city over the Fourth of July three-day holiday. Will 300,000 more be here this weekend? Testing transportation If nothing else, the existing transportation grid will be put to the test with three major events — the Garth Brooks concert, the UFC fights and Bruno Mars — occurring at venues within a half-mile of each other at right around the same time that night. But health officials have expressed concern that big crowds have the potential to create superspreader events. Nevada on Thursday reported 697 new coronavirus cases and two deaths as the state’s test positivity rate continued to climb.