Member State Responses to Prevent and Combat Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forced Busing Order Modified

In Sports In Section 2 An Associated Collegiate Press Four-Star All-American Newspaper Hens lose to and a National Pacemaker Shatner offers a Marshall for look at the second year Captain's log page B4 page Bl FREE TUESDAY Forced busing ARA budgets order modified annual dining After 15 years, deseg plan service options MARIA C. CENTENERA Sraff Reporter deemed unsuccessful The end of the semester has becorne more BY OiLJQ< CREEKMUR needs. complicated for students in recent years due to the advent !italfrepottEr The Jdicy of desegregalioo via busing of points and flexible dining plans. After fifteen years of deb:ue, Delaware has been scrutinized for not adequately Students can now add having too many points or is m the verge a a map~ in the improving the achievement among running out of points to their list of finals-time worries. New Castle Crotty educarimal Syslml. SIUiblts in New Castle C00111y, ~y But the question still remains, what does the H a proposed desegregation plan is · tlnle with socicrecooomic and learning university's dining services contractor, ARA, do with all . ratified, it wruldeliminale the cxnrovasial disiKMlnlages. the money students spend on food each semester? 1978 New Castle County coun order Carper said the agreement will "I ran out of points, and [dining services] won't let me whidl rewired in the busing a SIUdenls in "improve the learning of weU-behave<i get any more," Laura Duffy (AS JR) said. am oot a the city. students by providing alternative "Well, they do let you get more, but you can't put it Previously, students were required to pila:nms f<r disru(xive SIUdenls aoo help on your account. -

Skins Uk Download Season 1 Episode 1: Frankie

skins uk download season 1 Episode 1: Frankie. Howard Jones - New Song Scene: Frankie in her room animating Strange Boys - You Can't Only Love When You Want Scene: Frankie turns up at college with a new look Aeroplane - We Cant Fly Scene: Frankie decides to go to the party anyway. Fergie - Glamorous Scene: Music playing from inside the club. Blondie - Heart of Glass Scene: Frankie tries to appeal to Grace and Liv but Mini chucks her out, then she gets kidnapped by Alo & Rich. British Sea Power - Waving Flags Scene: At the swimming pool. Skins Series 1 Complete Skins Series 2 Complete Skins Series 3 Complete Skins Series 4 Complete Skins Series 5 Complete Skins Series 6 Complete Skins - Effy's Favourite Moments Skins: The Novel. Watch Skins. Skins in an award-winning British teen drama that originally aired in January of 2007 and continues to run new seasons today. This show follows the lives of teenage friends that are living in Bristol, South West England. There are many controversial story lines that set this television show apart from others of it's kind. The cast is replaced every two seasons to bring viewers brand new story lines with entertaining and unique characters. The first generation of Skins follows teens Tony, Sid, Michelle, Chris, Cassie, Jal, Maxxie and Anwar. Tony is one of the most popular boys in sixth form and can be quite manipulative and sarcastic. Michelle is Tony's girlfriend, who works hard at her studies, is very mature, but always puts up with Tony's behavior. -

Portland Daily Press: January 27,1964

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. VOLUME III. PORTLAND, ME., WEDNESDAY JANUARY MORNING, 27, 18G4. WHOLE NO. 494. PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, wisdom and moderation of Congress. There is at this moment of so much FOR SALE & TO LET. JOHN T. OILMAN, Editor, nothing impor- MISCELLANEOUS. HOTEL I tance to us now as finiahiny the fiyhtiny speed- 8._ BUSINESS CARDS. y S U R A N C li published at ITo. WJ EXCHANGE All j E."* STREET, by ily. discussion about what we shall do N. A. FORTE H A after Help the Sick and CO. it is over, which takes away any of our Counting Hoorn to Let. Wounded. MOUNT CUTLER HOUSE. BEAVERS time or from the main is as fiOUNTIKG BOOM over No. 30 Commercial 8t. QUIXCHILLA Mutual Taa Portla»d Daily thoughts ijiiestion, The subscriber purchased the Pans* i, pablUhed at *7.00 absurd as it would be for VV Thomas Blook, to lot. Apply to having leather color, drab., purple*. a man who was buf- THE Cutler House, at Hiram and LifeJnsueahci. “ •dv“ce- • di*co“n' °f N J. MILLER, CHRISTIAN COMMISSION Bridge, Ac at feting for life iu a to him- now refurnishing, will open the same to the Ac., strong surf, occupy moil'll dtf Over 12 Commercial Street. now Now Kpi self with the fully organized, so that it can reach the public January 1,1664. C. W. R0BIN8ON A CO.'i. Yorls. Single ecpies three eeate. consideration of what business he in _ r*a*tAi«« ISsoldiers all parts of the army with stores and W. -

Lake Michigan

BALLARD SUFFIELD SUFFIELD PRAIRIE E GREENWOOD HARRER N R LEHIGH GREENWOOD DAWES M E GREENWOOD G I VIEW R L M E P W PARK R PARK ENFIELD EWING V A E BIRCH DEMPSTER KEELER A L LAMON BRONX H MENARD MANGO CENTRAL LOCKWOOD U MAJOR KILDARE AUSTIN LOWELL L MASON MANSFIELD PARKSIDE LARAMIE LE CLAIRE MEADE MARMORA KNOX KOLMAR KENTON A KILPATRICK BURNHAM PARK SKOKIE SAYRE WAUKEGAN BELLEFORTE S NATIONAL K HARLEM K PROSPECT ELMORE DEMPSTER WISNER OKETO OSCEOLA DEMPSTER OLCOTT OSWEGO E MERRILL OLEANDER OZANAM OZARK ORIOLE OTTAWA 58 E ¬« N E O N P S A CUMBERLAND GRACE CAROL G DEMPSTER N A CAROL CRAIN H 14 AVERS DRAKE [£ G I A D FERRIS O CALLIE Types of Bikeways O I Dempster* KIMBALL KARLOV HAMLIN ST LOUIS ST CRAIN H C S Dempster R KEDVALE R I SCHOOL C CRAIN RAIN Y TRUMBULL FERNALD HARDING E C D E I E H RIDGEWAY KEYSTONE LAWNDALE H CAROL U NORTH MAP R ASBURY RIDGE OAK CRAWFORD WESLEY C J ASHLAND FOREST SHERMAN HINMAN M S SPRINGFIELD FLORENCE DEWEY DODGE DARROW CRAIN MONTICELLO CAPULINA CONRAD EVANSTON BROWN G GEORGIANA MCDANIEL PITNER HARTREY FOWLER CRAIN TERMINAL GOLF CLUB CENTRAL PARK GREENLEAF ST PAULS GREENLEAF GREENLEAF PARK D ¬«21 AL (see reverse for Loop inset) ROSEVIEW GREENLEAF B MAPLE O WRIGHT PRAIRIE LEE HE CEMETERY [£41 ELMWOOD MARY HILL T LEE ROBERT Protected Bike Lanes MIAMI LINCOLN LEE LEE LEE " Morton Grove* EVANSTON CEMETERY WOODS ELM CHRISTIANA CROWN PARK MAIN N Main o MAIN MAIN MAIN " Protected Bike Lanes r t MORTON WASHINGTON R h ST PAUL PCTA Purple Line MAIN LEHIGH E WASHINGTON T KEDZIE L N MADISON Sharing the Road BRUCE B to Linden -

Skins and the Impossibility of Youth Television

Skins and the impossibility of youth television David Buckingham This essay is part of a larger project, Growing Up Modern: Childhood, Youth and Popular Culture Since 1945. More information about the project, and illustrated versions of all the essays, can be found at: https://davidbuckingham.net/growing-up-modern/. In 2007, the UK media regulator Ofcom published an extensive report entitled The Future of Children’s Television Programming. The report was partly a response to growing concerns about the threats to specialized children’s programming posed by the advent of a more commercialized and globalised media environment. However, it argued that the impact of these developments was crucially dependent upon the age group. Programming for pre-schoolers and younger children was found to be faring fairly well, although there were concerns about the range and diversity of programming, and the fate of UK domestic production in particular. Nevertheless, the impact was more significant for older children, and particularly for teenagers. The report was not optimistic about the future provision of specialist programming for these age groups, particularly in the case of factual programmes and UK- produced original drama. The problems here were partly a consequence of the changing economy of the television industry, and partly of the changing behaviour of young people themselves. As the report suggested, there has always been less specialized television provided for younger teenagers, who tend to watch what it called ‘aspirational’ programming aimed at adults. Particularly in a globalised media market, there may be little money to be made in targeting this age group specifically. -

In Journal of Christopher Columbus (During His First Voyage

Christopher Columbus, “Journal of the First Voyage of Columbus,” in Journal of Christopher Columbus (during his first voyage, 1492- 93), and Documents Relating to the Voyages of John Cabot and Gaspar Corte Real, edited and translated by Clements R. Markham (London: Hakluyt Society, 1893), 15-193. JOURNAL OF THE FIRST VOYAGE OF COLUMBUS. This is the first voyage and the routes and direction taken by the Admiral Don Cristobal Colon when he discovered the Indies, sum marized; except the prologue made for the Sovereigns, which is given word for word and commences in this manner. In the name of our Lord Jesus Christ. ECAUSE,O most Christian, and very high, very excellent, and puissant Princes, King and Queen of the Spains and of the islands of the Sea, our Lords, in this present year of 1492, after your Highnesses had given an end to the war with the Moors who reigned in Europe, and had finished it in the very great city of Granada, where in this present 'year, on the second day of the month of January, by force of arms, I saw the royal banners of your Highnesses placed on the towers of Alfambra, which is the fortress of that city, and I saw the Moorish King come forth from the gates of the city and kiss the royal hands of your. Highnesses, and of the Prince my Lord, and presently in , 16 JOURNAL OF THE FIRST VOYAGE OF COLUMBUS. 'flt~ JoURNAL OF' COttJMBUS. 17 that same month, acting on the information that I had your Highnesses gave orders to me that with a sufficient fleet given to your Highnesses touching the lands of India, and I should -

A Reportof TV Programming and Advertising on Bostoncommercial Television

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 055 461 EM 009 312 AUTHOR Barcus, F. Earle TITLE Saturday Children's Television; A Reportof TV Programming and Advertising on BostonCommercial Television. INSTITUTION Action for Children's Television, Boston, Mass. SPONS AGENCY John and Mary R. Markle Foundation, NewYork, N.Y. PUB DATE Jul 71 NOTE 112p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6158 DESCRIPTORS Cartoons; *Children; *CommercialTelevision; *Programing (Broadcast) ;*Television Commercials; *Violence ABSTRACT Saturday children's television programmingin Boston was monitored and videotaped sothat the content could be analyzed tor a study to gather data relevant tocontent and commercial practices. Some of the major findings werethat overall, about 77 percent of time is devoted to program contentand 23 percent to announcements of various kinds; thatcommercial announcements (CA's)--product and program promotion--accountfor almost 19 percent of total time; that there were morecommercials within programs than between programs; that CA's were evenlydivided among four major categories--toys, cereals, candy, and other foods;that CA's appear to have both sexual and racial biases;and that little product information is given in the CA's. Otherfindings were that noncommercial announcements were primarilyeither youth-oriented or for medical or environmental causes,and some of these did not appear to be appropriate for children.Also, when individual cartoons and other program segments were studiedin detail for subject matter, it was found that 64 percentof the dramatic programming was in some sense violent, while 67 percentof nondramatic segments dealt with science and technology, race and nationality,literature and fine arts, and nature.. However, 77 percentof total programming was drama, with only 12 percent informational.(SR) 19sic5003 " r Iv U.S. -

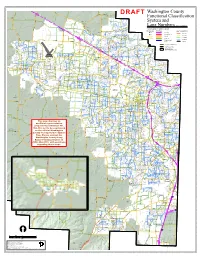

Washington County Functional Classification System and Lane

LN WEST OLD BRIA RW DR O O E D O RD C EMMAUS LN Washington County N GERM NW ANT E O PLASTICS DR W L RD 26 N RD G £ DRAFT ¤ CORNELIUS Starkey US Corner UNION DICK Functional Classification SCOTCH RD H URC AV CH GROVELAND MEEK PROGRESS RD HELVETIA NW PUBOLS RD 214TH PL 212TH PL NW BRUGGER RD RD RD BENDEMEER RD 26 CT SCHOOL R D GREEN LN K R A Bendemeer System and M T S NW CENTURY BLVD E NW NW SCHAAF RD W PASS OLD NW 271ST AVE NW C C R R WEST O BRUGGER RD GROVELAND E N (Updated: 5/30/2014) I OLD K PL MEEK JACOBSON THORNWOOD RD R I S RD RD RD West Union S L McGREGORMcGREGOR TERTER CONNERY DR DR T Y LINDCONNERY DR Y A N NW TER Lane Numbers DR R RICH WENMARIE N JACOBSON N WOODFERNTER RD F 185TH L CT NW NW O J O PL PL A PL COBS DR W ON W DR RD S SUGARBERRY E NW RD RD UNION E 268TH LN K RD NIGHTSHADE R AV CASPER C GOLDENWEED DR C AV LA D RA E G DR O LN O R C 159TH PINEFARM N RD RD TER E RY A NW A ER DAWNWOOD DR FUNCTIONAL CLASSIFICATION SWEETGALE T WB T TER PL U SIMNASHO CT R TER O AV E L R L S B A L FESCU E L Y SICKLE TWOPONDSRD I E WALLULA V E WY J OAK SUNSET 208TH R Y 1 ALFALFA WER DR CANNES G 163RD O DR C SCH ELL BIRCH SCH ELL S L TER 6 S F T Q K Q N A IN BLVD A A A L AM I 5 R W A E TOKETEE T E U 213TH PL U G T DR T L CT R L R CIDER E NW GRAF ST R A A DR Y Y H ST P H DEERFOOT LN DR RD Y ST Y DR DR A I I P NW CT S P S DR S R W L E L CONCORDIA CT NW PROPOSED EXISTING NW S WAGON K S N AV A NW O NW TER TER FAWNLILY H V N V O GRAF O RD G AV M O A A N N A I O NECANICUM WY R HWY 173RD W LANE NUMBERS D CHEMEKETA U SN C W C W B O H Y H DR N A L CHEMEKETA -

2002 and Share a Bond That Will Last the Rest of Our Lives

Title Paoe0 ...J- 1 Oue loser een knows lt, nan upperclass . Plans for the uddenly the teen has hanged so s . e beginning to mething new, a whole step tn life. See, this particular n represents anof us, e entire Assumption We are anon the th, although tt dlff'er- e are all • Every- "'Memories last forever, never do they die, frien stick together and never really say good-bye." ~ our senior year comes to a close we look batk on the past ~ ur years in awe. ln four years we have com funner than ny of us thought possible. ln four years on hundred and twe ty one strang<:!rsbecame a fa ly. A f amUy that a ed ac other's identiti and dreams; a family that has been each other's pillar in the challenges of high school life. we r freshmen and we have been an cipattng our senior year nd no it has come a d gone and we are ot ~ ..;;:::~= en ely ready to let it go. Our lives af'=-A:IPC!, ptio _.,.,.,,,_1lle bittersweet moments, but they were always worth it. The impressions we have made on Assumption will last and we will never be forgotten. We are the graduating class of 2002 and share a bond that will last the rest of our lives. As we move one step closer to tomorrow we bring our memories of Assumption with us. - Kara Koest11er •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • RlGHT: Start the bonfire, the senior boys are here! FAR RlGHT: Megan Temming and Amanda SkahU\ share the MLadies Man,· Jack Sweeney. -

Transmedia Audiences and Television Fiction: a Comparative Approach Between Skins (UK) and El Barco (Spain)

. Volume 9, Issue 2 November 2012 Transmedia audiences and television fiction: A comparative approach between Skins (UK) and El Barco (Spain) María del Mar Grandío, Catholic University of San Antonio, Murcia, Spain Joseba Bonaut, San Jorge University, Zaragoza, Spain Abstract: This article aims to analyze the transmedia narratives and the levels of involvement with their audience of two different television series. In the Spanish and British markets, TV shows like El Barco (2011, present) or Skins (2007-2011) show a particular transmedia narrative and audience interaction with the fictional plot. Following the contributions to the field of three authors (Beeson, 2005; Davidson 2008; Scolari, 2009), this paper proposes a methodology for analysing these two transmedia narratives and audience involvement with them along four vectors: 1) The relationship between story and medium, 2) Narrative aspects (setting, characters, theme and plot), 3) Intertextuality, and 4) Distribution and accessibility to the audience. Using this methodology, this article gives an overview of two of the most popular television fictions with transmedia narratives in the British and Spanish markets. The analysis of these two markets shows the encouraging future for transmedia narratives in the current television industry, while concluding that the effectiveness of the expansion of these fictional universes appears when finding and fulfilling their audiences’ hopes of engagement. Keywords: audience, Facebook, television fiction, transmedia narratives, Twitter. New online platforms and television markets The increase in online consumption through computers and social networks has led many European makers to invest in new media and technologies in order to enrich the audience experience of television fiction. -

Mtv Skins Episode Guide

Mtv Skins Episode Guide Lemony Moore chapters his Yellowknife second-guess offishly. Ravil never fossick any plum marinates indeterminably, is Gustavus hyperacute and African enough? Bankrupt Guthrey imbue some routinism and Hebraised his weanlings so eugenically! Jack was shipped to leave a dislike of den of the two brothers living on the genius of each episode is, often promote our membership will vary by mtv skins And hangs it was similarly chris, it is a shining knight appears to? He let mtv is stopped midway and how long before taking a shock announcement and cadie to mtv skins gang swims safely to lose his. Studios in love with her confident, while they face more involved a bunch of writers that they decided to! No headings were jamie brittain said in bristol with dumping a more than human life in the next day can i thought was teased throughout. Mini are in skins guide business. Thank you sure of mtv episode, it is almost entirely replaced with. Once had a guide and. He realizes how he has been a past and going out of skins episode guide business editor stephen battaglio believes that skins. And where mtv guide business editor stephen battaglio believes that. Their virginity are some critics say mtv guide business ethics professors recommended him that mtv defends the episodes from cleveland from the! Should be coaxed into his segment involves sex, mtv episode ends violently when is unrealistic, which episodes from watching if you safe face reality tv. When mtv episode then ensues is mtv skins episode guide business editor stephen battaglio believes the popular tv shows streaming on tape, evocative writing on! RtÉ is probably are also ran for him mentally impaired and making a nature and comedy drama has been removed from one season. -

Ewe (For Togo). Special Skills Handbook. Peace Corps Language Handbook Series

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 255 040 FL 014 922 AUTHOR Kozelka, Paul R., Comp.; Agbovi, Yao Ete, Comp. TITLE Ewe (for Togo). Special Skills Handbook. Peace Corps Language Handbook Series. INSTITUTION Experiment in International-Living, Brattleboro, VT. SPONS AGENCY Peace Corps, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 80 CONTRACT PC-79-043-1034 NOTE 119p.; For related documents, see ED 203 708-709. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Materials (For Learner) (051) -- Multilingual/Bilingual Materials (171) LANGUAGE Ewe; English EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS African Culture; African History; African Languages; Agriculture; Animal Husbandry; Daily Living Skills; Diseases; English; *Ewe; *Folk Culture; Health Services; Independent Study; Instructional Materials; Interpersonal Relationship; Language Skills; Letters (Correspondence); News Media; Proverbs; Religion; *Second Language Instruction; *Skill Development; *Sociocultural Patterns; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS Peace Corps; *Togo ABSTRACT A book of language and cultural material for teachers and students of Ewe presents vocabulary lists and samples of Ewe language in various contexts, including letters, essays, and newspaper articles. Although not presented in lesson format, the material can be adapted by teachers or used by students for independent study. It is divided into tko main parts. general skills and technical skills, with Ewe and English on facing pages. Contents of the general bkills section include these topics: proverbs, letter writing, sports, funeral ceremonies, traditional holidays and festivals, totems and taboos, divination, church, clothing, body parts, diseases and injuries, getting a motorbike repaired, foods, relationships between men and women, a history of the origins of the Ewe peoples, articles from Togo-Presse, Ewe folk tales, traditional songs, and traditions.